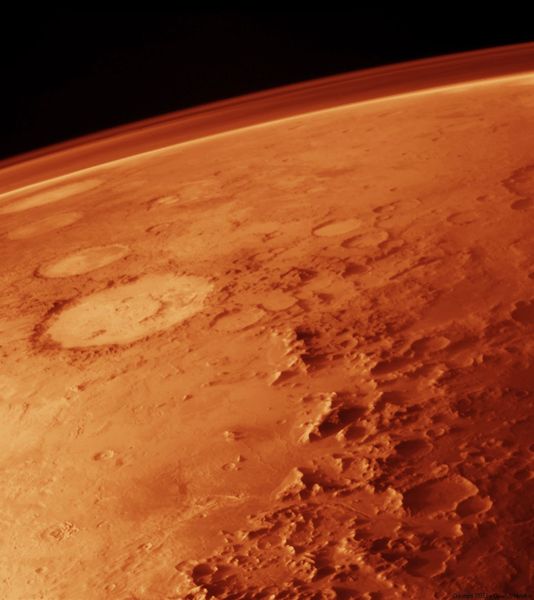

Life on Mars

Interview with

Classic David Bowie song or legitimate scientific question? Many believe Mars may have, at some point in time, harboured life, and one of those people searching is Steve Pointing, director of the Institute for Applied Ecology at AUT, who explained why we're looking for life on Mars.

Steve - Mars is our closest neighbour and to understand why it's worth looking  there, it's more than just proximity and getting there easily. It's also about understanding a concept. That concept is known as the habitable zone. So essentially for any star like our sun, there is a very small zone around that star that is able to support planets that can harbour life. it's really a confluence of two functions. Number one, the planet needs to be just the right distance from that star to allow water to exist as a liquid. So, if it's too far away, the water is cold and frozen. If it's too close, the water is evaporated and not available. And the second thing is the planet has to have enough mass to retain an atmosphere, such that gases that are useful to life like carbon dioxide, like oxygen are retained, but heavier and more toxic gases are not retained.

there, it's more than just proximity and getting there easily. It's also about understanding a concept. That concept is known as the habitable zone. So essentially for any star like our sun, there is a very small zone around that star that is able to support planets that can harbour life. it's really a confluence of two functions. Number one, the planet needs to be just the right distance from that star to allow water to exist as a liquid. So, if it's too far away, the water is cold and frozen. If it's too close, the water is evaporated and not available. And the second thing is the planet has to have enough mass to retain an atmosphere, such that gases that are useful to life like carbon dioxide, like oxygen are retained, but heavier and more toxic gases are not retained.

Chris - Do you know they were going to build a nightclub on Mars, but they said it was crap because there's no atmosphere?

Steve - Great! Parking would be an issue anyway. Yeah, it's interesting. Funny enough, going on from that though, there's actually a Dutch TV company who've been advertising for a bunch of individuals to take a one way trip up to Mars for a reality show.

Chris - But they're all old people when they said old people only because they didn't want anyone who was going to come back. They said, a.) it would affect the budget and b.) there was danger of radiation exposure because NASA did with the Curiosity rover that landed almost two years ago this weekend. It's going to be 2 years of Curiosity rover that came down.

Steve - It's 2 years this week, yes.

Chris - They use the radiation sensor on Curiosity to measure the incident radiation exposure that it got during the - because over half a billion kilometres of travel to Mars, isn't it?

Steve - That's right. Six months in a cramped spaceship.

Chris - Equated to basically an astronaut's entire working lifetime sort of radiation exposure just making that journey.

Steve - Absolutely and that's largely because there is no atmosphere to block out those harmful incoming rays. So yeah, it would be absolutely unimaginably large task to get people living up there permanently. But you know, we have to aim big. The simple truth is that when one considers our star, it has a finite lifespan and we're a single-planet species at the moment. And so really, philosophically, we have to ask ourselves, do were really want to admit that once planet Earth becomes uninhabitable that we're going to die out. So, that's really - from my mind - is the philosophy behind exploring Mars.

Chris - What makes you think that Mars might have life on it at all?

Steve - Well, it's a good question. The sort of life we'd be looking for - let me be clear - is not little green men. I don't think we're expecting. We're not really looking at that. the reason is this - I've got a bit of show and tell for the people listening. I'm holding up a rock at the moment which has a rather smudgy green line just beneath the surface. This is the surface of the rock here and this green line is about 20 mm below the surface and this is the sort of life that we expect to encounter on Mars. This particular rock is actually from Antarctica but Antarctica is what we call a Mars analogue. It's the closest thing on Earth that we have to Mars surface. It's very cold, it's very dry, and it's relatively high radiation levels there because the atmosphere is thinner at the poles. This sort of life, although it's green, it's not a green man or a green woman, it's actually cyanobacteria which are very, very primitive plants. They're single-celled microbial plants essentially. That's the sort of thing we're expecting to find.

Chris - Just to be clear, they can actually thrive in the temperatures. They're actually viable at the sorts of temperature you see in Antarctica.

Steve - Well, they're not viable at surface temperature. The temperature on Mars can be anything down to minus 110 degrees which biological reactions just won't occur there. But these organisms are just below the surface. The reason is that in Antarctica for example, they're exploiting very marginal gains in temperature and humidity that occur below the surface. And so, the reason Curiosity for example has a drill on it is that NASA's aim is to drill into the rock and thereby, try to identify whether life is either present or has been present in the past which is probably our best bet.

Chris - Have they found anything yet?

Steve - No. Curiosity doesn't have a primary aim to search for life. Curiosity actually is looking for the chemical conditions that could've supported life. So for example, how sustained was the presence of water on the surface. But in 2020, there is a sort of an amped up version of Curiosity going to be launched which will have a slightly adjusted payload and that will have a direct aim to search for life. that is a good segue to our previous speaker because it's actually using lasers. In this case, a Raman spectroscopy laser to try and identify compounds that are specific to life and in particular, these green life forms, the cyanobacteria.

Chris - So, you've looked in rocks from Antarctica and then presupposed that if life does exist on Mars, it's probably going to be sort of similar or have similar chemistry to the life we see in extreme environments here on Earth that are sort of similar. So, if we therefore go looking for those same sorts of chemical hallmarks on Mars, that's the best place to go looking.

Steve - Yeah. I mean, there are arguments for and against this strategy. I mean, some people could argue why would life be DNA-based for example as all life on Earth is. But the simple truth is that chemistry has arrived at the most parsimonious solution for life. The simplest solutions were often the best. And so, we know that there are certain compounds in life that are very good indicators and in particular, not necessarily DNA, but actually, compounds such as chlorophyll for example, a potentially very good indicator for life.

Simon - So this habitable zone, Mars is basically the convenient option.

Steve - It is a convenient option.

Simon - Six months, I mean, that makes your trip through the violet pretty easy, isn't it? You were whinging about that.

Chris - What? My trip down here?

Simon - Yeah.

Steve - Yeah. I'm not sure what the land should be like. But the great thing about Mars is looking at Mars' immediate past. Probably as little as 5 million years ago, Mars very possibly was pretty much like maritime Antarctica is now. It was much warm and much wetter and quite conceivably could've supported life. and that's largely a result of the obliquity of the planet, having changed quite radically.

Chris - Why do you think that's happened? Why so recently?

Steve - Well, this is down to astronomers, but quite simply, the angle of tilt for the planet Mars has changed from about 45 degrees to about 23 degrees which is more or less identical to Earth. It's just in the last 5 million years. Of course, the poles, with that much more exposed to the sun and most of the waters at the poles ergo there would've been much more water. That's really the basic prerequisite for life.

Chris - Because it's very recent, isn't it that it's undergone such a dramatic shift.

Steve - Yeah, I mean, it is an estimate of course but those that know in the astronomy field stick by that.

Chris - So, do we think then because life got started on Earth very quickly by 3.9 billion years ago and the planet is only 4.5 billion years old. We've got evidence that there were little cells already here going about their business on Earth. Do we think that probably the same thing was happening in parallel on Mars then?

Steve - Well, a lot of people believe so. I mean, life on Earth, there are traces for life on Earth pretty soon after the lunar cataclysm and life could've even conceivably originated before then, but being wiped out by the - as you may know, there was a very large impact of planet Theia that proto planet Theia that impacted early Earth. The mess that resulted as ejected into space form our moon. So, nothing really survived. But very soon after as you say, life evolved. But a lot of people believed that life could've evolved on Mars because Mars, although it's slightly outside the perfect habitable zone now was actually once in that zone, and will actually enter that zone again in the future. So yeah, a lot of people believe life could've co-occurred on two planets. Of course, that brings up some really amazing philosophical questions.

Chris - Do you think that if there is life on Mars now, do you think that it could be in a sort of stasis, sitting, waiting, so that when the sun gets a bit warm and swells up a bit as it ages, that life could come back to life as it were?

Steve - Yeah, it's quite possible. I mean, one of the things about microbes that's really remarkable is their ability to essentially go dormant for very, very long periods. We've retrieved bacteria from ice cores thousands of years old that are viable. So, it's as quite conceivable.

- Previous Love thy virus

- Next Problem solving lasers

Comments

Add a comment