Immune attack on the brain

Interview with

It's becoming increasingly clear that the immune system plays a role in a number of nervous system disorders, including schizophrenia, depression and Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. Belinda Lennox, from Oxford University,  has been studying patients who present with psychotic symptoms caused by an immune attack on the brain. Kat Arney hears from her what causes episodes like the one suffered by New York journalist Susannah Cahalan, heard here speaking to Hannah Critchlow...

has been studying patients who present with psychotic symptoms caused by an immune attack on the brain. Kat Arney hears from her what causes episodes like the one suffered by New York journalist Susannah Cahalan, heard here speaking to Hannah Critchlow...

Susannah - This was 2009 that my symptoms started and I was 24. A lot in my life was very new. I had just started a full-time job as a news reporter, new apartment, new boyfriend, kind of living on my own in New York City for the first time. I started to feel not like myself. At first, I just kind of chalked it up to the fact that I'm in this new environment. I have this new life. Of course, I don't feel like myself. So, I felt very lethargic, I couldn't really concentrate at work. I was kind of moody. I was sleeping a lot. I became kind of obsessive about certain things, for example, I thought that I had bed bugs. An exterminator came in and said I didn't but I was obsessed with it anyway. I became convinced that my boyfriend was cheating on me and kind of went through all his belongings. I just thought, you know, I'm just not feeling like myself because I'm in the middle of a new life and that's what I chalked it up to in the beginning at least. But things quickly escalated from there. So, from just a month of not feeling of myself, all of a sudden, I was not myself in an extreme way. Pretty much overnight, I stopped sleeping, I stopped eating. My emotions which were already kind of influx went wildly out of control. One moment, I would be crying and then the next moment, I'd be laughing, I'd be on top of the world like the best I've ever felt. It was very confusing for me.

Hannah - And then you were almost sectioned to a psychiatric hospital.

Susannah - What happened was, I had my first seizure. I emerged from that extremely psychotic. Paranoia, I believed everyone was out to get me and then I began to hallucinate shortly after. So, I was actually seeing and hearing things that were not there. I believed that my mum had hired actors. When we returned to the doctor's office when I was released from the hospital, I believed she had hired everyone there as actors because she wanted to play a trick on me. She wanted to teach me a lesson. At one point, I was at my father's house, the room was kind of coming alive and the paintings were moving. The room almost had this energy like it was breathing. I remember as clear as day, hearing my dad hitting my stepmother. And again, this is all in my head, but this was as real as anything in my life. I thought he was going to come and get me next. I remember looking out the window. He's about 3 floors up and I looked at the window and thought, I can jump and escape. My stepmother keeps a Buddha statue in the bathroom and it smiled at me. So, I did not jump. After that night, my parents were very concerned about my safety. The doctor was worried that I was suffering from partying too much. My parents were adamant. They said, "No. there's something seriously wrong here, she needs to go to a hospital" and they won.

Hannah - Sounds absolutely terrifying - the whole experience - for yourself and also, your parents. So, what happened then? Did they reach a diagnosis quickly?

Susannah - I was in the hospital for a month, about 3 and a half weeks before we got a diagnosis. My clinical picture changed starkly. So, it started with extreme psychosis and I got even more psychotic when I went to the hospital. I saw myself on the news, I was trying to escape, I was ripping out EEG wires from my head, and IVs from my arm, and I had to be restrained and heavily sedated. My symptoms began to change and this actually scared my parents more than the psychosis because I started to become catatonic. I stop really speaking, my tongue hung out of my mouth. I just wasn't really there. At this point, what I'm relating to now is all from my parents and my medical records. I don't have any memory of this. But every single test that was conducted, they all came back negative. So, on paper, I'm a healthy person but they still did not have a cause. They couldn't figure out what was wrong with me. And then about 3 weeks in, a man named Souhel Najjar was called on the case.

Hannah - You had one little test I believe to help with your diagnosis.

Susannah - Yeah. It's incredible to think about it. He asked me to draw a clock, very simple. He kind of came up with this idea on the spot while he watched me do it. I had trouble forming the circle, I had trouble with the numbers and I would write them several times. And then when he looked down at my finished result, the whole left side of the clock was completely blank. That showed him the right side of my brain was very impaired.

Kat - So, that's quite a distressing picture that we've heard from Susannah about her symptoms and the clock test she was asked to do sounds like almost something off the TV show "House". So, how would people be diagnosed in this kind of situation if everything is coming up not right? What's going on here?

Belinda - Well, it was almost by chance really that Souhel Najjar thought that Susannah had something atypical because to all intents and purposes, her story was typical from my perspective of a psychotic illness, of a severe Schizophreniform, kind of acute psychosis. There was nothing in there to really raise alarm bells that there was anything different about her presentation. The test of the clock face is just a test of visuospatial processing. It's a bedside cognitive test. It's not very specific, but it does, I mean, he's right; it indicates that there's something going on in the brain if you want to be as crude as that. But he took that to mean that she needed further investigation and he looked further.

Kat - So then what was going on in her brain and how was it diagnosed?

Belinda - So, she had NMDA receptor antibody encephalitis and she was...

Hannah - Wow! That sounds complicated.

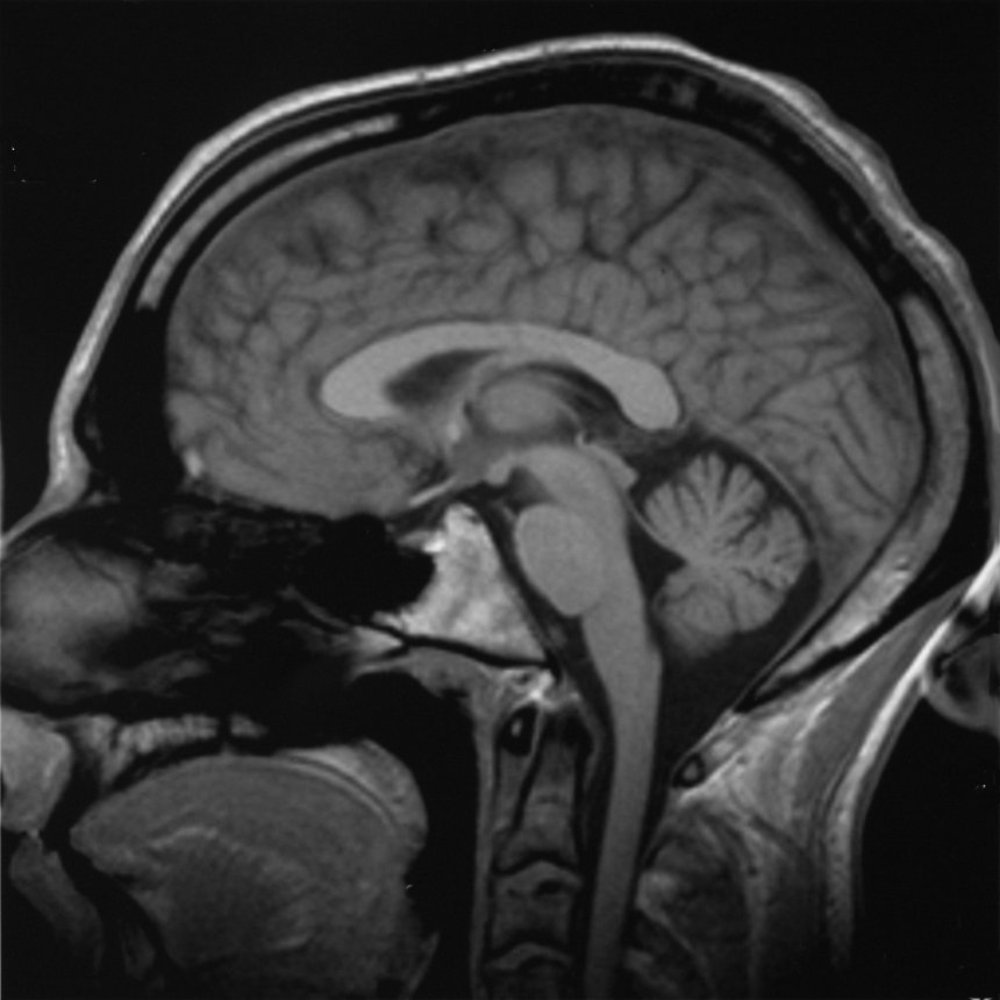

Belinda - It's a long name, but it's an antibody against a very common brain protein, the NMDA receptor that is fundamental for a whole range of brain functions. The antibody was only first described a year before Susannah started in her illness in 2008. So, she was incredibly lucky that Dr. Najjar had heard of it and actually, it was only after extensive investigations and a brain biopsy that they thought of testing for this antibody because all other investigations were completely normal. That's what we see in patients with this disorder; all other investigations are negative usually. And patients usually receive the diagnosis of Schizophrenia or a psychotic illness prior to having a positive blood test for this antibody.

Kat - So, let's unpick this a little bit. You're talking about an antibody. What is this antibody? It's something made by the immune system, so what's going on?

Belinda - Well, antibodies are produced by everybody. They're normal response usually to infection or to tumours or to other insults to the body. But sometimes they're produced against our own organs just as what we term an autoimmune disorder. This disorder was originally described in association with benign tumours - teratomas usually and the antibody was described in young women usually, with their ovarian teratomas. That was thought to precipitate the production of these antibodies. But since then the sort of the description of the disorder has broadened so that usually, we don't find a teratoma and we're assuming that this is an autoimmune disorder. The body is producing these antibodies against itself.

Kat - Now, this presents a bit of a problem because as with any autoimmune disease, your body is doing this against your own tissues. How do you go about treating something like this?

Belinda - Well very crudely, we suppress the immune system. So, we stop the production of antibodies. We give steroids and we also flush out the antibodies that are already in the system using treatments such as intravenous immunoglobulins or plasma exchange which is...

Kat - So, you kind of wash someone's blood basically.

Belinda - Absolutely. You flush out the antibodies that are there already and you replace them with plasma that doesn't have antibodies.

Kat - Well, Susannah had a treatment. So, let's find out from her how she faired on it.

Susanna - It took me anywhere from about a year and a half to 2 years to kind of return to base level of who I was before. In terms of the way I see the world now, I mean, it's changed everything about my life. You know, a big part of my reason for existing now is to kind of talk about this disease and others like it. I'm very interested in mental health issues and the idea, and the stigmatisation of mental illness. I mean, all these questions have emerged in my life that did not exist prior to having this illness. I think you can't really go through something this traumatic - this frankly interesting - I mean, it's a fascinating disease - and not have a change in your world view...

Kat - It is certainly is absolutely fascinating. So, Belinda, Susannah said things have started to go back to normal, it took a long time. But given what we know about how the immune system is a bit of an unknown quantity, could there be a problem with this disease returning?

Belinda - Absolutely. So in the cases where we don't find a teratoma or an obvious cause for the antibody being produced, there is certainly a risk of recurrence. Although we've only been seeing patients with this disorder for the last 7 years or so, we are seeing in about a third to a half of cases, we see recurrences and relapses. So, we need to suppress the immune system for a good couple of years. That's our current thinking anyway to keep people well.

Kat - When people think about psychosis, I mean, you do think about Schizophrenia and there are other psychotic conditions. But do you think that this kind of thing could be underlying maybe other types of psychosis or other sort of very severe mental disorders?

Belinda - Absolutely and even Susannah's story, she had a very prominent effective component, a mood component to her illness. Alongside her psychotic symptoms, she describes a wildly fluctuating mood state as well. And so certainly, from the cases that we've seen, there's a mixture of symptoms. So, it's not restricted to Schizophrenia-type presentation at all.

Kat - We'll be going on to look at some other mental health conditions that might be linked to the immune system. But what it wanted to pick up on briefly with how Susannah says, she wants to de-stigmatise the disease and I think with physical illness, you can kind of say, "Okay, that's wrong with you. You've got a cancer or you've broken your leg" but are we starting to now understand some of the actual, the physical things that are going wrong to cause mental health symptoms and that we should say, these are illnesses just like physical illnesses?

Belinda - Absolutely and some of the work that we've been doing has described that about 5% to 10% of people presenting with a first episode of a psychotic illness presenting to psychiatric services have these antibodies against the NMDA receptor and other neuronal cell surface proteins. So, it's vitally important that we look for these antibodies because it could result in a dramatically different treatment approach for these patients.

Kat - And this is one particular antibody. Where next? Are you looking for others that might be involved?

Belinda - Yeah. So, there's a whole range of different antibodies against different cell surface proteins that have been described. So, the voltage gated potassium channel antibody, GABA receptor antibody, glycine receptor antibody - I could go on.

Comments

Add a comment