What Causes Alzheimer's Disease?

Interview with

Ben - Alzheimer's disease is a common cause of cognitive decline amongst elderly people. An estimated one person in every five over the age of 80 is affected, and develops a range of symptoms including memory loss. The cause of the disease is a build up in the brain of a protein called beta amyloid which damages nerve cells, but why does this happen? Chris Smith spoke to Randy Bateman, a neurologist at Washington University in St. Louis...

Randy - So, there was a basic question which we began to consider about four or five years ago, and the question was, what causes Alzheimer's disease? And that question has been asked for a long while, but this was more directed at the current thinking about what causes Alzheimer's disease in relationship to what's known scientifically. There's an amyloid hypothesis which specifies that build up of a protein called amyloid beta, which is normally made by our brains, that this increase in this protein in the brain leads to damage that causes the symptoms of Alzheimer's disease. Now the basic question that we were asking was in Alzheimer's disease, does the amyloid beta build up there because it's being produced too much, or made too much in the brain, or is it there because once made, the brain has a problem clearing it away? Some of the basic information about amyloid beta is that the brain normally makes this, the neurons or the thinking cells of the brain normally produce this amyloid beta protein in the brain, and it's normally cleared away and it doesn't build up into very high amounts. But what we also know is that in patients that have Alzheimer's disease, their brains are filled and littered with this substance up to 100 to 1,000 fold normal levels. So it builds up at very high levels and this is thought to be toxic to the brain and cause damage, ultimately culminating in dementia of the Alzheimer's type.

|

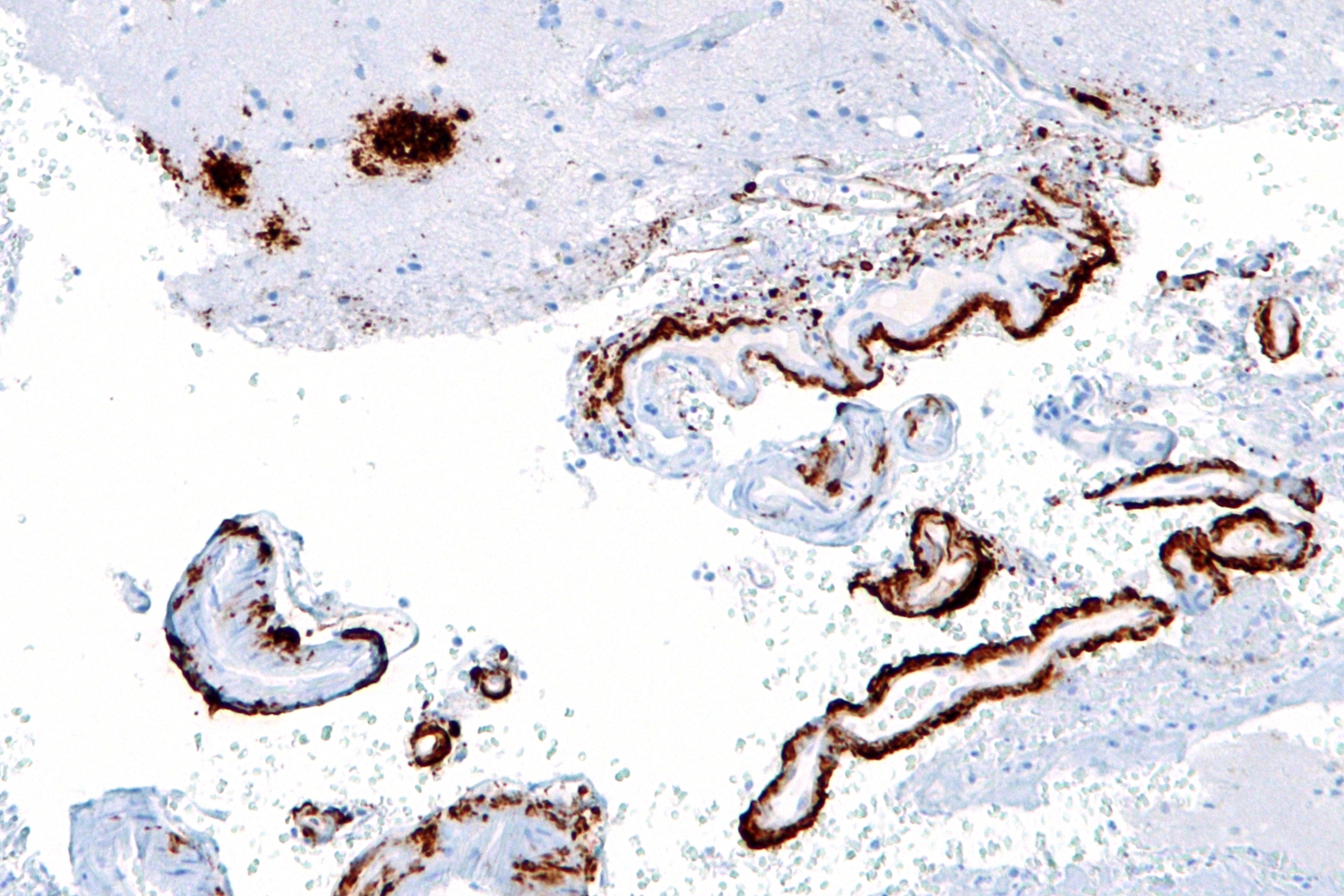

Micrograph showing amyloid beta (brown) in senile plaques of the cerebral cortex (upper left of image) and cerebral blood vessels (right of image) with immunostaining. © Nephron @ Wikipedia |

Chris - So you've got two problems there. One of them is, that there's too much being produced or is it that it's not being dispensed with, dealt with by the brain as it is in a healthy person's brain? So how can you try and disentangle those two?

Randy - That was the challenge and that's where the technique was actually developed to answer this question. Essentially, the way to do this is to label the proteins as they're being made so you can track them. And then once a protein is labelled then you can track how fast it's being produced, how quickly it's being cleared away. The first publication of the method itself was in 2006 where we reported what normally happens in young healthy people with amyloid beta in the brains in terms of its production and its clearance rate. And often, I use an analogy that this labelling system - imagine that you have a single water and you have a faucet on with water coming into the sink, and you have a drain that's draining the sink at the same time. If you just look at the sink and you don't look at the faucet or the drain, you only see a level of water in the sink, and that's what we normally measure when we sample the fluid that surrounds the brain. We measure how much of that amyloid beta protein, or the water level, is there. One way to track how fast it's coming in is, you can imagine that if you dyed the water coming out of the faucet a certain colour, say blue, that the water in the sink would turn bluer and bluer over time, the more blue water came into it. And if you watch over time, how much of that water has been labelled with that - in this case, a colour label. In the case of the amyloid beta protein, we're using a label that's just slightly heavier for the protein then we can estimate how fast the production or the rate of water coming in to the sink is. And by the same token, if you stop labelling and then you watch the water as it's cleared away, new fresh clear water comes in and the blue is cleared away, you then have an estimation of how fast the sink is draining that water. And so, this is what we do. We take a label that incorporates into the protein, it's an amino acid which is a building block of proteins which our body normally makes, and it's slightly heavier than normal amino acids. We infuse that into the bloodstream of the person and all the proteins that person is making can be tagged with this label, marking it as newly made. Then we sample over time the fluid that surrounds the brain, it's called cerebrospinal fluid and we watch the appearance of this newly labelled amyloid beta protein, and then we stop labelling and we watch how that labelled amyloid beta is cleared away over time.

Chris - And you did this in healthy people and you did this presumably in a group of Alzheimer's patients to compare the rate of production and removal of the beta amyloid in the brains of both?

Randy - Exactly. And so, in this study, what we did is we compared 12 people who have Alzheimer's disease to 12 people who don't have Alzheimer's disease, but are about the same age, and we compared the two to find that there was a significant decrease in the clearance of amyloid beta. But on average, there was no significant change in the production rate of amyloid beta.

Chris - The only problem with this study is that it tells you about people who've already been diagnosed and it would be very interesting to wind the clock back in their lives, or look upstream - look in people who are going to develop Alzheimer's disease or just look in people who are viewed as healthy, and then follow them up, and then see who does get Alzheimer's disease and see if there's anything lurking upstream in those people.

|

Alois Alzheimer |

Randy - That's exactly right. That's an insightful point and one which we're planning on doing as the study goes on and participants come in to the study. We're in fact following each individual over time clinically so that the cognitively normal people that have done this study, they don't all have exactly the same production in clearance rate. Some are faster and some are slower and so, the basic question is, are the people who have slightly impaired or impaired clearance but are cognitively normal now, are those people with increased risk of getting the disease at some point in the future?

Chris - How do you know that the people who have got Alzheimer's disease now haven't just got a reduced clearance because the disease has in some way damaged the brain, and the reduction of nerve cells that is associated with Alzheimer's disease has just impaired their ability to get rid of it? And that's why you're seeing that; As a consequence of the disease process, not so much as a consequence actually of having caused the disease.

Randy - With its current data, there's no way to distinguish between those two possibilities. And although we may hypothesise that for example, decreased clearance may lead to increased levels of amyloid beta and plaques, that's not demonstrated in this particular study. That's the point of doing the ongoing research, to determine if that's correct or not.

Ben - Randy Bateman, a neurologist who's looking for a way to knockout Alzheimer's disease on the head. He was talking to Chris Smith and has published that work this week in the journal Science.

Comments

Add a comment