Inside the Intestines

Interview with

Meera - This week, I've come to the school of Food Biosciences at the University of Reading to find out how the bugs in our body can actually help with our health. Bacteria are literally everywhere on Earth and us humans depend on them a lot. One of the ways we depend on them is to help us digest our food. A team here at Reading are using a model of our large intestine to find out just how these so-called good bacteria work. I'm here with Dr Gemma Walton, gut microbiologist at Reading University, who's going to tell me more about how these models work.

Gemma - The large intestine is the region just after the small intestine. It comprises the proximal, the distal and the transverse colon regions.

Meera - What's different between these regions?

Gemma - The small intestine is quite an acidic environment so the beginning of the large intestine is slightly acidic. It gets less acidic and more neutral as you move to the more distal regions.

Gemma - The small intestine is quite an acidic environment so the beginning of the large intestine is slightly acidic. It gets less acidic and more neutral as you move to the more distal regions.

Meera - Here, with the models I can see we've got three main bottles. I guess these are representing each part of the intestine?

Gemma - Yes, we've got out proximal, transverse and distal regions. They're held at different pHs so different acid levels by pumping in acid to each of the vessels just to maintain them.

Meera - At the front we've got a slightly larger bottle which seems to be feeding into the first stage of the large intestine and then onwards. What's in that large bottle?

Gemma - In that first large bottle would be non-digested foods that would typically arrive in the large intestine to be broken down further by the bacteria.

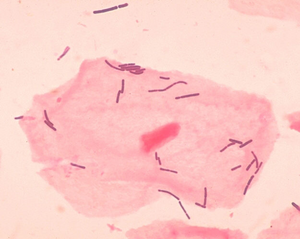

Meera - What bacteria are found in the large intestine then?

Gemma - There's many, many different species of bacteria in there. Typically, we have species of lactobacilla, bifida bacteria, clostridium, bacteroides, eubacteria. We used to believe the large intestine was just the area for the absorption of water but now we can see there's millions and millions of bacteria. It's actually a very metabolically active organ of the body.

Meera - How did these bacteria get there in the first place?

Gemma - It starts off at birth. When a baby is delivered vaginally the first time it is in contact with bacteria is when it leaves its mother. It's basically getting a vaginal inoculum straight away when it's born. There's lots of different species like lactobacillus in the vaginal tract. This is the first meal, if you like, that the infant will get. These bacteria that get into the infant will then use up the oxygen very rapidly. Therefore you get an area that's got no oxygen which is what we're left with. A system with lots of bacteria growing that don't use oxygen.

Meera - Once these bacteria are down there, how do they actually help our digestion?

Gemma - When you ingest a meal it goes down and it's ingested by your own enzymes and broken down in your small intestine. However, there's loads of partially digested foods actually reaching the large intestine. For example, there's some different starch molecules and the longer-chained carbohydrates that are reaching the large intestine. These can then be further broken down by the bacteria in the large intestine and broken into short chain fatty acids and other products that might be beneficial to human health.

Meera - We've got this model showing the large intestine. What are you actually trying to find out?

Gemma - In these models, this is the gross part. What we actually do is we place a faecal suspension into each vessel of the model. This is our way of putting in the bacteria that have been naturally found growing in the intestine. We're just adding them in, holding them in the different pHs according to the acid levels. We can now feed the model with different prebiotics. Prebiotics are carbohydrate-based normally. What they are, they're food for the bacteria so they're tested to see if they actually grow on them. We can feed this into our first vessel of the system and see how they affect the bacteria within there and see whether they increase beneficial bacteria and whether this can persist in the second and third vessels: whether we can actually have changes in our beneficial bacteria. We can also look at probiotics. Probiotics are actually the beneficial bacteria so we can see by having a probiotic meal what it actually does when these bacteria are mixed in the system, whether the bacteria that are ingested actually have a chance to coexist with the bacteria that are already there.

Gemma - In these models, this is the gross part. What we actually do is we place a faecal suspension into each vessel of the model. This is our way of putting in the bacteria that have been naturally found growing in the intestine. We're just adding them in, holding them in the different pHs according to the acid levels. We can now feed the model with different prebiotics. Prebiotics are carbohydrate-based normally. What they are, they're food for the bacteria so they're tested to see if they actually grow on them. We can feed this into our first vessel of the system and see how they affect the bacteria within there and see whether they increase beneficial bacteria and whether this can persist in the second and third vessels: whether we can actually have changes in our beneficial bacteria. We can also look at probiotics. Probiotics are actually the beneficial bacteria so we can see by having a probiotic meal what it actually does when these bacteria are mixed in the system, whether the bacteria that are ingested actually have a chance to coexist with the bacteria that are already there.

Meera - What have you found so far? How well has it combined?

Gemma - Different probiotics have shown some very nice results that they can work nicely with the bacteria. What we also find is that if you stop taking these the bacteria then leave the system.

Meera - So to improve your health you have to have a regular intake of them?

Gemma - Absolutely, it seems like it's the transient effect.

Meera - What result have you seen with the prebiotics, basically the things that are feeding the bacteria in your intestine. Has that been positive?

Gemma - Yes, absolutely. This is a nice way to increase the numbers of bacteria already there, the beneficial ones. We've been able to see nice increases using systems like this. In some instances we can see persistence of the prebiotic to causing increases in the more distal regions which is the area more prone to diseases.

Comments

Add a comment