Predicting solar eruptions

Interview with

The UK Met Office recently launched its space weather forecast centre to help protect us from the threat of severe space weather events.

protect us from the threat of severe space weather events.

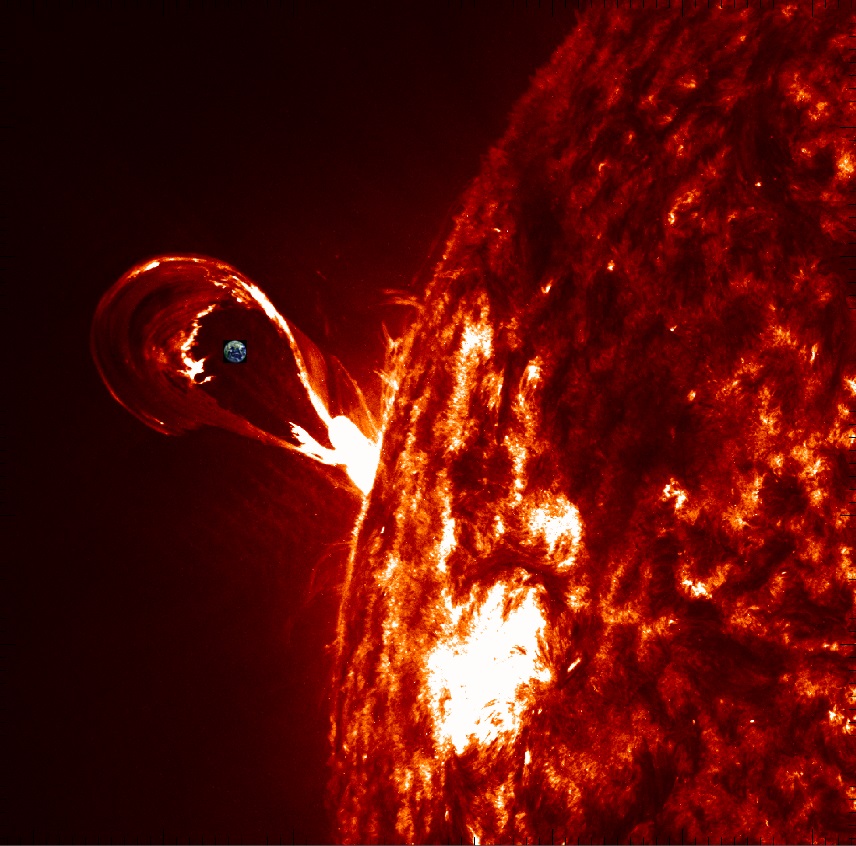

So-called solar storms begin as a sudden flash on the Sun's surface followed by a "coronal mass ejection" - a radioactive maelstrom of particles that surge out into space. If this hits the Earth it can damage satellites, knock out GPS systems and destroy power stations.

So how predictable are these events and what causes them? A team led by Tahar Amari at the Ecole Polytechnique near Paris has studied a previous one in detail and now they think they know.

Chris Smith has been looking at the study, published in the journal Nature, with Reading University solar scientist Chris Scott...

Chris S. - One of the things that drives space weather are huge eruptions in the sun known as coronal mass ejections. Each one of these is about a billion tons of material. If one of this comes towards the Earth, it brings with it a magnetic field which can disrupt the Earth's magnetic field and lead to all kinds of consequences for our satellite and ground based infrastructure. So, predicting when one of these mass ejections is going to erupt is really the holy grail of the science.

Chris - What is frustrating our efforts to do that at the moment?

Chris S. - Well, the sun's atmosphere is an incredibly complicated soup of electrified plasma that's churning around and generating very complex magnetic fields. We know that something happens to reconfigure those magnetic fields, which allows the material to erupt from the surface. Because it's so complicated, several mechanisms have been proposed as to which one would be the cause of such eruptions.

Chris - Is that with prediction in mind?

Chris S. - Exactly that, yes. So, the Met Office called this ensemble forecasting. You run them up many times with slightly different initial conditions. And so, you can then get a probability of what it's like - in the weather forecasting terms, you can say, "60% chance of rain." With this, you could look at the sun and the solar atmosphere and you can say, "Well, there's a 60% chance that a mass ejection will be erupted from this region."

Chris - This new paper, what have they done and what does this add?

Chris S. - So, in this one instance, it looks like they've actually been able to model, pretty successfully, the evolution of that magnetic field and this knot a material on the sun, and predict when it was going to erupt into a mass ejection. The challenge is to go from this one observation where you have the benefit of hindsight and you can wind the clock back and you can wind it forward and you can hone your model to match the data. Can you then do that to make a genuine prediction? Can you observe these initial conditions and say how the solar atmosphere is going to erupt?

Chris - How much of a threat are events like coronal mass ejections to the Earth?

Chris S. - We have an increasing reliance on space infrastructure for navigation, for communications. So, modern technology is becoming more vulnerable to the vagaries of these conditions in space. We've only been really been measuring these things in space for the last 50 years or so and we know that the likelihood of a really major mass ejection is maybe once every hundred years or so. So, anything that we can do to predict when they're going to come will enable us sort of batten down the hatches as it were.

Chris - That was going to be my next question, Chris. What could we do about it?

Chris S. - A spacecraft is going to be sitting amongst these particles and there's not really much you can do about it, but what you can do is you can turn off any high voltage electronic systems on the spacecraft. It's a bit like the advice we get, don't drive on the motor ways if it's very windy for example. They're just saying, the risks are higher, so if you can possibly avoid it then do so.

Chris - What about, any 'would-be' space tourists or people who happen to work in space, astronauts aboard the international space station for example?

Chris S. - What you need to do is to just make sure the astronauts are not outside and exposed to the worst of the conditions. There are even a couple of places on the space station which have a little bit more shielding than anywhere else. So, you could get your astronauts to shelter in there.

- Previous Drones that can 3d-print...

- Next Can a Little Bit of Stress Help?

Comments

Add a comment