Mouse ultrasound

Interview with

A few years ago, scientists discovered that mice squeak at each other using ultrasound. But studying why they produce these vocalizations, which animals make them and when, and in response to what stimuli has always been a major challenge. And this is owing in part to the constraints of how ultrasound behaves and how to detect it. Now, Joshua Neunuebel from the Janelia Farm Research Campus has developed a system to allow him to localize the sources of these sounds in 3D space and in real time. And he's already busted one myth. Both sexes, not just the males, make them. He explained to Chris Smith...

always been a major challenge. And this is owing in part to the constraints of how ultrasound behaves and how to detect it. Now, Joshua Neunuebel from the Janelia Farm Research Campus has developed a system to allow him to localize the sources of these sounds in 3D space and in real time. And he's already busted one myth. Both sexes, not just the males, make them. He explained to Chris Smith...

Joshua - They're emitting these sounds ultrasonically, and so these are really high pitched sounds. And we can't hear them, and so, it requires specialized microphones to actually detect these sounds. And so, we can't really put a microphone on the mouse to figure out which one's vocalizing. And so, we decided to actually just take advantage of physics. Sound travels at 340 meters per second. And the closer you are to this, the sooner you're gonna be able to detect these sounds. And so, we decided to use math and physics to sort of pinpoint where the sound was coming from.

Chris - This gives you an insight then into which animal is producing a sound in what sort of setting without actually having to interfere with the animals at all.

Joshua - Yes, exactly.

Chris - And what does it show then, when you do that?

Joshua - So, the field has believe when you put a male and a female together, that it's always the male that produces these vocalizations. And the reason for that is if you anesthetize the female and you put a male in, he'll run around and vocalize. But if you do the opposite and you knock out the male and put a female in, she doesn't vocalize. And so, the field has believed that males produced these vocalizations. And so, what we showed and with normally freely behaving animals, females do vocalize.

Chris - Tell us a bit about your sort of set up then. How do you physically do these recordings?

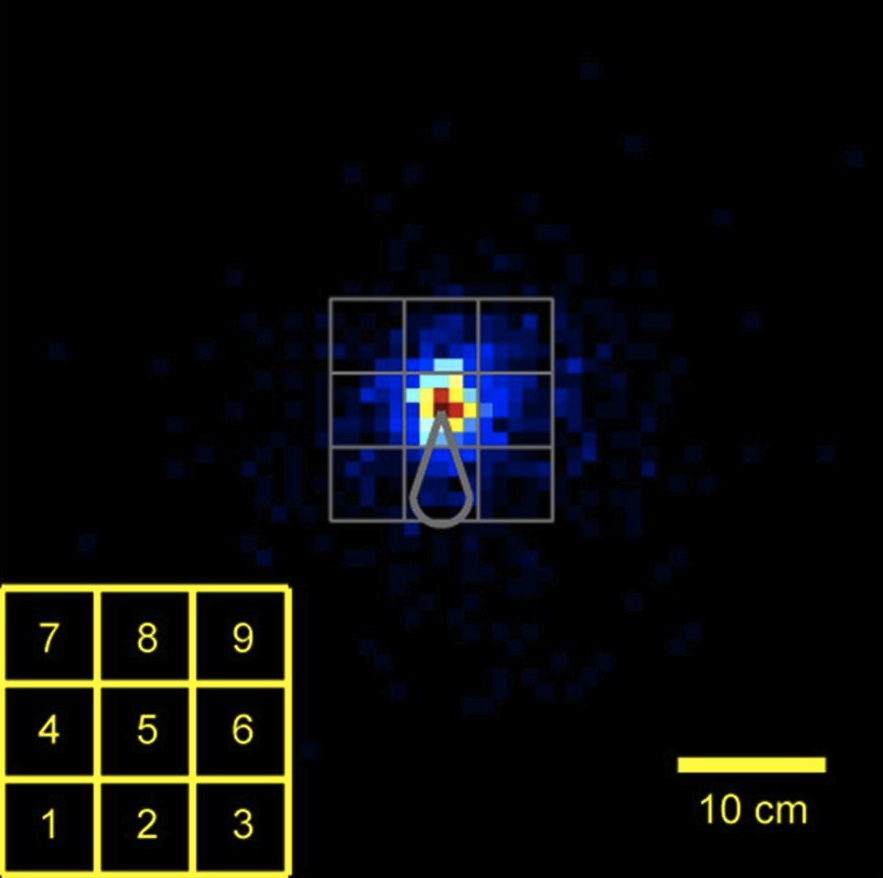

Joshua - What we do is, basically, we build a microphone array and that means we have multiple microphones positioned around the arena where the animals run around. And normally, ultrasound in incredibly reflective, so if it hits a plastic wall or hits something hard, it's gonna be bounced back. If that's occurring, it makes it really difficult to localize the sound. So, what we did was we built this acoustically transparent cage. So, the ultrasound can actually pass through this cage because the cage is made out of this nylon mesh, and then it passes through and gets detected by these microphones on the outside in the periphery. And there's also some foam on the outside that helps absorb this and prevents the bounce back.

Chris - And how many animals can you resolve at once? Is it just pairs that you can accurately resolve with this, or could you go to bigger groups?

Joshua - In the paper that we published, we went up to four animals. So, it's two males and two females.

Chris - So, this is quite literally a triangulation effect. You basically are recording from multiple microphones and you can time how long it takes the sound to arrive at each of the different ones, and you can match them up and you can say, "Right. Okay. That must be coming from that animal, that animal, or that animal."?

Joshua - Precisely. Yeah.

Chris - So, what problem can you now apply this to? So, you've done the initial detection right. We've shown that for the first time that the male and the females, they're both vocalizing. But what will you be able to now test next? What's the next step?

Joshua - So, there's a lot of different steps, actually. And so, I just actually started my first faculty position this year and so, what I want to do is I want to start applying this to different autism models. And so, if you look at a lot the autism mouse models out there, you see impairments in social behavior and you see impairments in, what they say, communication. And that means there's a reduction in the number of vocalizations. But we don't really know if there's a deficit in vocal interaction between these animals. So, I'd like to actually go in and use autism models and see if there are impairments in vocal communication.

Chris - What about if the mice don't feel like talking?

Joshua - Well. It's gonna be a bad day in the house.

Chris - Does that happen? How often do they produce these sounds so that you get meaningful data?

Joshua - It depends on the conditions. And usually, if you pair a male and a female mouse together, they will vocalize. And so, as long as they're together, you're gonna get some data. Maybe not as much as you want but you'll get data. One of the things we did, for male mice, they'll vocalize to female urine. So, they don't need a partner in there. Like, they habituate to those conditions very quickly. And so, that's the more variable part. How often are you going to get vocalizations to, like, external stimuli or a different stimuli. But if put a male and a female together, you'll get some data to look at.

Comments

Add a comment