Stress and depression

Interview with

Depression is tightly bound up with stress, exposure to which can often precipitate an episode that, as well as causing characteristic mood changes, also leaves its mark on some of the nerve cells of the brain's prefrontal cortex, connections between which shrink. Now we're a step closer to understanding why. Prerana Shrestha has been using tracing and genetic techniques to identify these affected nerve cells and she's found that they're the same population hit by the rare condition "Wolfram syndrome", suggesting that the causative WFS1 gene might also play a role in depression. She spoke to Chris Smith about what this could mean for depression research...

an episode that, as well as causing characteristic mood changes, also leaves its mark on some of the nerve cells of the brain's prefrontal cortex, connections between which shrink. Now we're a step closer to understanding why. Prerana Shrestha has been using tracing and genetic techniques to identify these affected nerve cells and she's found that they're the same population hit by the rare condition "Wolfram syndrome", suggesting that the causative WFS1 gene might also play a role in depression. She spoke to Chris Smith about what this could mean for depression research...

Prerana - Major depressive disorder is a highly heritable common mood disorder characterised by lack of motivation, reduced ability to derive pleasure from natural rewards, and abnormalities of sleep and appetite. Given strong evidence that bouts of depression can be elicited by stress and that stress strongly impacts the medial prefrontal cortex, we were interested in identifying circuit elements in this brain area that contribute to the relationship between stress and depression.

Chris - So, how did you try and home in on what those circuits might be?

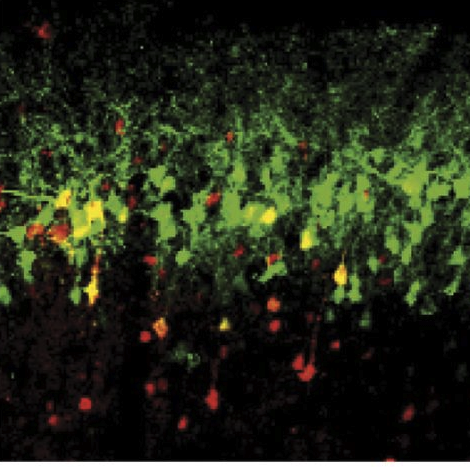

Prerana - In order to discover the cells in medial prefrontal cortex that express genes implicated in human depression, we employed molecular profiling in the mouse cerebral cortex including genetics, vital tracing method, behaviour analysis and biochemistry, we identified a novel cell population that expresses the causative gene for wolfram syndrome.

Chris - What actually is wolfram syndrome?

Prerana - Wolfram syndrome is a multisystem disorder that first presents in the form of diabetes type 1 and type 2. But in the second decade, patients develop psychiatric symptoms.

Chris - Isn't it interesting that the circuits highlighted by your tracing studies also seem to be implicated where wolfram syndrome manifests in the prefrontal cortex?

Prerana - Right. We wanted to study specifically the role of this gene in medial prefrontal cortex so we employed transgenic strategy to create a double transgenic mouse so that we can delete this gene from conception in forebrain excitatory neurons. We also at the same time applied another strategy to delete this gene in adult mouse to avoid any negative impact during development of disrupting this gene.

Chris - When you make these knockouts, what do they show you? What syndromes do these mice develop?

Prerana - Deletion of this gene in either the entire cerebral cortex or the medial prefrontal cortex specifically during conception or during adulthood rendered these mice highly susceptible to acute restrained stress. For example, behavioural despair in forced-to-swim test or anhedonia in sucrose-preference test.

Chris - Do you know what the gene is doing in the cells that express it, in order that when you don't have it there, you get this sort of funny syndrome in these mice?

Prerana - So, it is known in pancreatic beta cells that WFS1 makes a protein that resides in endoplasmic reticulum and is involved in processing of various peptides including insulin. We were not aware until our study whether WFS1 protein has the same role in the medial prefrontal cortex neurons. Using electron micrography, we showed that WFS1 indeed is present in the endoplasmic reticulum of the medial prefrontal cortex neurons. In addition, we did biochemistry in mice cortical extracts from mice that were either exposed to stress or in baseline conditions. We found that exposure to 30 minutes of acute stress caused an impairment in processing of several important neuropeptides and growth factors including Wnt7A and neurotrophin factor 3.

Chris - One would speculate then that if this gene is dysfunctional, it doesn't work properly in either a human or a mouse, then what it does is it robs that population of cells of their ability to secrete those neuropeptides and this will have downstream effects on the targets which will have behavioural consequences.

Prerana - Right. Indeed, we found that once this gene was deleted, the hypothalamic pituitary adrenal stress access was hyper elevated in response to stress.

Chris - Do you think then that in an individual who develops just endogenous depression, they just become depressed for some reason as anything up to one in five people do at any one time, do you think that what's happening is that they've got a similar impact on this gene in their brains?

Prerana - Wolfram syndrome is a rare disease that affects roughly 1 in 500,000 people. However, carriers of mutation in wolfram syndrome gene WFS1 are more common and they comprise 1 per cent of the population and they have an increased risk for major depressive disorder.

Comments

Add a comment