A guide to Gaia

Interview with

Where's it going? And what's it doing? Here's a whistlestop tour of the probe with  Graihagh Jackson...

Graihagh Jackson...

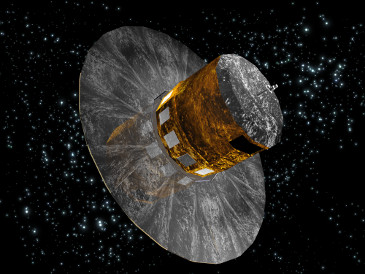

Graihagh - It's a probe - a bit bigger than those round trampolines every family seems to have in their back gardens these days - and you can think of it as being shaped like one of those floppy straw hats- a large rim with a bulbous centre.

Anna - Yeah it's on a very defined orbit actually.

Graihagh - Anna Hourihane...

Annie - And it's on a position known as the second lagrangian point, which is a kind of stable point in the Earth/Sun gravitational system. And it actually orbits not around the Earth, but it stays outside of the Earth and kind of keeps pace with the Earth in it's orbit around the Sun.

Graihagh - Okay. So it's kind of orbiting somewhere in between Earth and Mars then/

Anna - Exactly, yes.

Graihagh - And it's taking lots and lots and lots of photos of the stars because...

Gerry - The key parameter for Gaia is where the stars are.

Graihagh - That's Gerry Gilmore. He pitched the idea of Gaia to the European Space Agency and has been shepherding along the project ever since.

Gerry - You'd think the history of astronomy - people have been trying to measure where the stars are since the Mesopotamians. Actually, astronomers are not very good at this sort of thing and so, in the whole history of science we had reasonably accurate measurements of the positions and distances from us of about maybe a hundred thousand stars and how those stars were moving. Out of a hundred billion that's pretty pitiful really and they're all very local.

The reason for that is that space is big so it's really hard to measure the distances of stars. You need exquisite precision which Gaia provides. So Gaia is the first ever exquisite measuring system which is designed to measure not only where stars are. A large sample one per cent of them all - a billion or so but, also, how those stars are moving. So we get three dimensions in space of where the stars are.

Graihagh - And last month, the released the first data set.

Good morning ladies and gentlemen and welcome to the European Space Astronomy Centre (ESAC) here in Madrid. Today is an important day and a great day for astronomy because we are releasing the first batch of our data set from our Gaia mission. My name is Markus Bohrer, I am head of the communications office in ESAC and it's really a pleasure for me to welcome you here on site but also welcome to all those of you who are watching us on YouTube.

Graihagh - And scientists have been so excited about it all, that some have turned to the arts. Here's a poem that George Seabroke wrote - astronomer from the Mullard Space Science Labs.

Twinkle, twinkle little star,

How I wonder where you are,

ESA hovers up your light,

With our Gaia satellite.

The mission is to measure distance,

Get a grasp on your existence,

Gaia may not see you twinkle,

But kens if you're multiple or single.

Astronomers we feel the need,

To measure line of sight speed,

Gaia's radial velocity spectrometer,

Is the Milky Way's speedometer.

The Mullard Science Laboratory,

Has helped to write the Gaia story,

Has tested every key detector,

And coded software for billions of spectra.

Graihagh - Gaia has been making waves throughout astronomy. Although, I have to admit, when I was trawling through ideas for this episode, I emailed Duncan Forgan, astrophysicist at St Andrews for advice and he replied....

Duncan - I think if I can recall correctly, I think I just said oh there's one word for you and that's Gaia, and it's the one mission that every astronomer is excited about. And I think that's possibly the first mission since I started doing astronomy professionally, which has been almost ten years. And it's the first time I could really feel one mission really grasped everybody's attention. I think the only other thing that's really done that in all the time that I've known is Hubble, so it's on that level.

Graihagh - Erm, after that sort of response, how could I not start looking into it. Although, I did check, Duncan's not just doing an excellent PR job.

Duncan - I have no formal official connection to Gaia but I think every astronomer feels informally connected to Gaia because it's such an exciting mission.

Graihagh - Why is it such an exciting mission - you're a bit tantalising glimpse there?

Duncan - Well, it's so exciting because it's doing things on a scale that, when the mission was conceived twenty odd years ago, we didn't think was even possible. And we have what's going to be a huge data set, not just of many, many stars in the sky. So at the end of the survey it will be a billion stars, which is one percent of all the stars in the Milky Way, which makes it sound like a small number but it's still a huge number. And we'll not only just have that but we'll have a lot of information about asteroids in the solar system.

We'll even start and use this method to detect planets around some of these stars. So it's a huge data set for people who are interested in all kinds of different aspects of astronomy from the solar system to the stars themselves, to planets around other stars, and then to the galaxy itself, so how those stars actually fit into the galactic structure.

Graihagh - Bit mission then - not a small amount of data that they're collecting?

Duncan - It's a huge amount of data. So we have the first data release, or DR1, has just landed this week and that's still a huge data set, and it's only a small parcel of what's going to be a number of releases over five years. So even just that very small release itself is quite a lot to deal with.

References

- Previous How to map the Milky Way

- Next Mice grown from stem cells

Comments

Add a comment