In this NewsFlash, we explore the biofuel hope from the Burning Bush, the battle between Staphylococcus species and the chemical trick to reactivate dormant egg cells. Plus, the introduction of Synthia - the first microbe with a truly synthetic genome, and a BioBlitz in Bristol - recording biodiversity against the clock.

In this episode

00:15 - Burning bush brings biofuel hope

Burning bush brings biofuel hope

Have you ever seen a burning bush? These shrubs originated in Asia but have managed to invade North America. They're so-called because in the Autumn they have distinctive flame-red leaves. They look impressive, but are actually considered a bit of a pest, as they're an invasive species. But researchers at Michigan State University have made a discovery that could help turn the burning bush into the saviour of future biofuels, according to their paper in PNAS this week.

The burning bush produces an unusual oil, which could be very useful for fuel and food as it has quite a low viscosity - stickiness or thickness. Many plant oils are too thick to use in diesel engines, so they have to undergo a process to convert them to biodiesel. The oil from the burning bush is runny enough to use directly in diesel engines. And it's also lower in calories than other plant oils, so it might be useful for making low-cal foods. But unfortunately, burning bush plants aren't really suitable for agricultural growing and harvesting. So the researchers, led by WHO, sequenced the genes in a common ornamental species of burning bush, to find the gene that produces the key components of the oil - molecules called acetyl glycerides.

The burning bush produces an unusual oil, which could be very useful for fuel and food as it has quite a low viscosity - stickiness or thickness. Many plant oils are too thick to use in diesel engines, so they have to undergo a process to convert them to biodiesel. The oil from the burning bush is runny enough to use directly in diesel engines. And it's also lower in calories than other plant oils, so it might be useful for making low-cal foods. But unfortunately, burning bush plants aren't really suitable for agricultural growing and harvesting. So the researchers, led by WHO, sequenced the genes in a common ornamental species of burning bush, to find the gene that produces the key components of the oil - molecules called acetyl glycerides.

The scientists took the gene and used genetic engineering to add it to a plant called Arabidopsis - a type of cress commonly used by plant researchers. The modified plants then started making acetyl glycerides, producing oil with a purity up to 80%. So it's quite promising that they'll be able to produce high-quality oil on a large scale in the future, either by genetically modifying oil-seed crops such as oil-seed rape (known as canola in the US), or in other, more technological biological biofuel production systems, such as algae. They're not there yet, but these are exciting early results that will help to fuel further research, if you pardon the pun.

02:17 - Battle of the Bugs

Battle of the Bugs

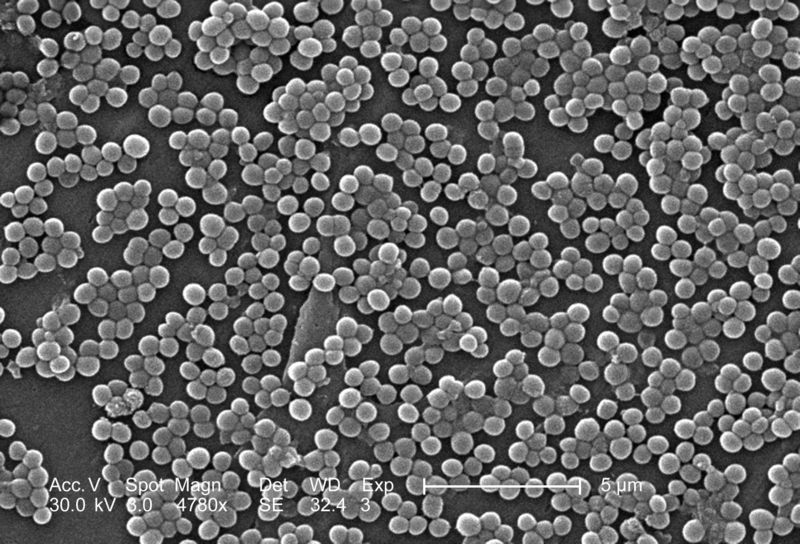

Researchers have discovered that the key to killing MRSA may lie with one of its own relatives. In a paper published in Nature this week, Jikei University School of Medicine scientist Tadayuki Iwase and his colleagues show how a common species of "good" bacteria frequently found on the skin, Staphylococcus epidermidis, produces a chemical weapon that disables its impetigo-inducing cousin, Staph aureus, includeing MRSA.

More than one person in three is colonised with Staph aureus, which is a risk factor for developing Staphylococcal infections elsewhere around the body, but some individuals seem to be able to evade carrying the bug in this way. To find out how, the team swabbed the nasal cavities, where Staph is known to lurk, of 88 volunteers. Predictably, twenty eight (32%) were Staph aureus carriers. But more than 90% of the volunteers were also carrying a second Staph species called Staphylococcus epidermidis, one of the most common human commensal or "good" bacteria and it seems that this friendly bug holds the key to kicking out Staph aureus in some people.

The reason, the team found, is that some strains of Staph epidermidis secrete a factor called Esp, an enzyme known as a serine protease, which behaves like the microbiological equivalent of a mace spray, dispersing crowds of Staph aureus and rendering them vulnerable to a bug-killing chemical secreted onto the skin by the immune system called hBD2 - human beta-defensin 2.

So why would Staph epidermidis want to kick out its own cousin? Pure selfishness is the answer. By taking up space and resources, Staph aureus is competing with its more human-friendly relative, which responds by poisoning it! It's tempting to speculate that it might be possible to exploit this newly-uncovered example of bacterial biological warfare as a novel way to deal with Staph aureus infections elsewhere in the body.

05:44 - Switching on egg production

Switching on egg production

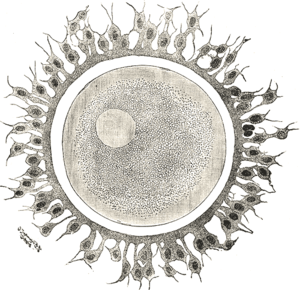

Unlike men, who are constantly producing new sperm cells, women have to work with a fixed number of egg cells from birth. Us girls are born with around 800,000 immature, dormant egg cells, known as follicles, and a couple of thousand of these are activated by hormones during each menstrual cycle, counting down our biological clock until the menopause. So there's a certain amount of time pressure on becoming a mum - at least in the biological sense. But now an international team of scientists, writing in the journal PNAS this week, have found a way to reactivate these dormant egg cells. And it could have big benefits for infertile women, or those who have had their ovary tissue frozen before treatment for diseases such as cancer.

This is work from Jing Li at Stanford University in the US, and researchers in China, Japan and America, and it all hinges on a gene called PTEN. Using mice, Li and her team found that shutting off PTEN using a special chemical could activate the dormant egg follicles in the ovaries of newborn mice - and when they transplanted these follicles into adult female mice whose ovaries had been removed, they could produce mature eggs and even baby mice.

This is work from Jing Li at Stanford University in the US, and researchers in China, Japan and America, and it all hinges on a gene called PTEN. Using mice, Li and her team found that shutting off PTEN using a special chemical could activate the dormant egg follicles in the ovaries of newborn mice - and when they transplanted these follicles into adult female mice whose ovaries had been removed, they could produce mature eggs and even baby mice.

It turns out that PTEN helps to switch off another gene called PI3K - this is makes a molecule that sends signals inside cells. Normally, PI3K works on a protein called Foxo3, changing its location inside follicle cells and triggering the follicle to mature. So blocking PTEN with the chemical means that it can't switch off PI3K, so PI3K can act on Foxo3, triggering the egg maturation process.

As PTEN is also involved in protecting our cells from cancer, there is a concern that blocking it might cause cells in the follices to develop into tumours, but luckily the researchers didn't find any tumours developing. Instead, the activated follicles developed into mature eggs, which could produce healthy baby mouse pups. And these pups grew into adults and had healthy babies of their own, suggesting there aren't any fundamental inherited problems with the cells or the DNA within them.

Obviously, it's more challenging to do these experiments in humans, but the researchers managed to do some tests on ovary tissue that had been taken from women having operations for ovarian cancer. Treating them with the PTEN-blocking chemical caused follicles to mature and produce egg cells, but unfortunately it seems that there might be some problems with them. So it's not certain that it will work in women, and a lot more research will need to be done before we know if we can use the technique to treat infertility.

07:59 - The creation of 'Synthia' - Synthetic life

The creation of 'Synthia' - Synthetic life

Victoria Gill, BBC Science Correspondent; Dr Craig Venter, J Craig Venter Institute

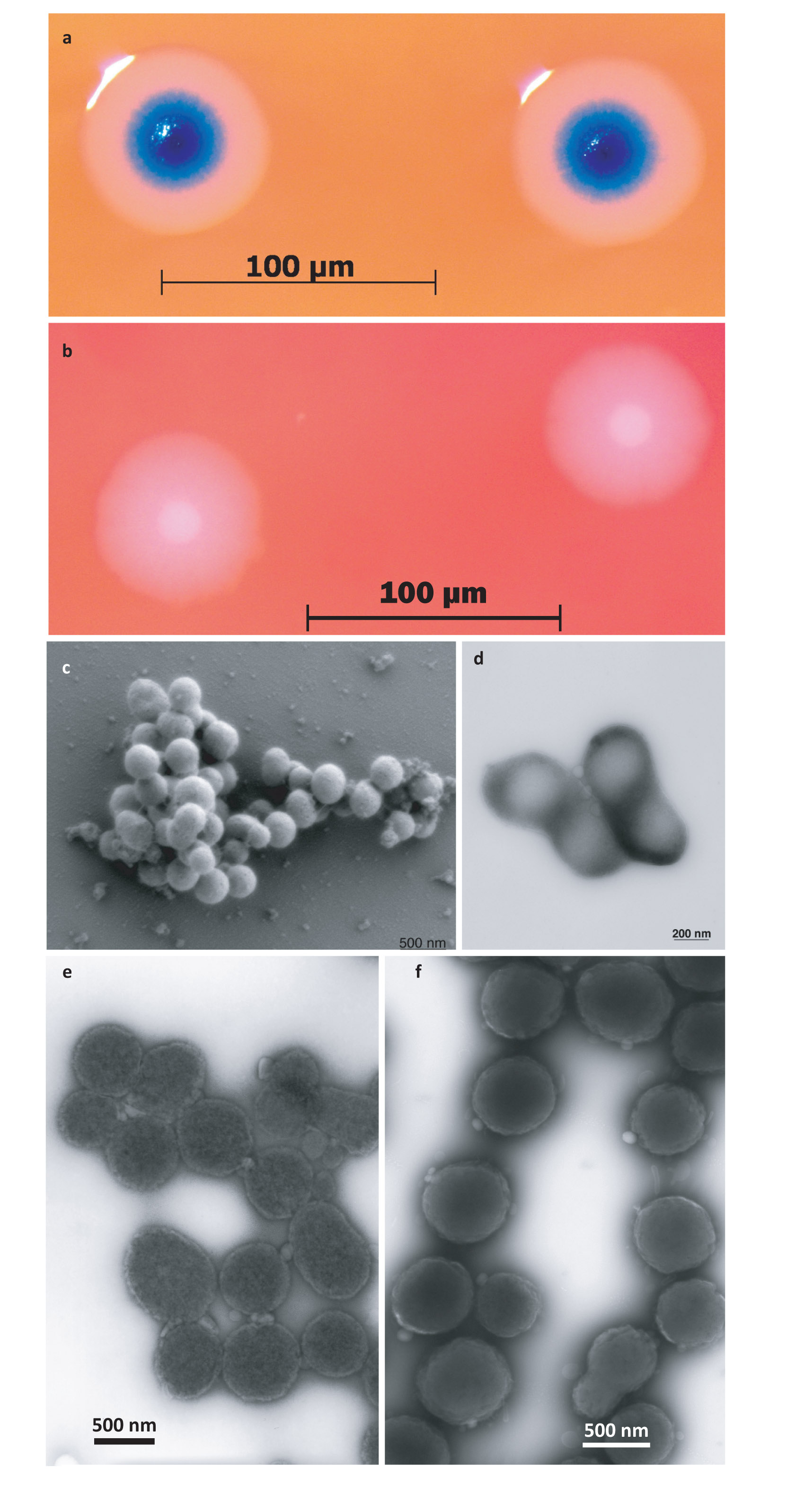

Chris - This week the J Craig Venter Institute announced the creation to huge fanfare of a brand new synthetic microorganism dubbed, "Synthia." This has prompted lots of excitement but also lots of controversy. Some people have argued that Synthia isn't entirely synthetic. So to tell us more here's Craig Venter and Victoria Gill.

Craig - Their generic heritage is the computer, so it is absolutely the first synthetic life form. A cell, driven, controlled totally by synthetic DNA. So, we call it synthetic because everything in the cell has been made and dictated by that synthetic chromosome even though we do start with another living species, we use that to initially read the genetic code and until it can transform itself into the species controlled and dictated by that synthetic chromosome.

Victoria - That's Dr. Craig Venter from the eponymous J. Craig Venter Institute, talking about his research team's new synthetic cells. But are they really synthetic cells? Is this synthetic life? Well strictly speaking, it's just the genome that's synthetic. What they've done is taken a copy of an existing bacterial genome, looked at all the DNA inside a simple bacterial cell, decoded that on a computer and then they've taken that and used the information to chemically construct a new genome, synthesising a genome in the lab from scratch. It's an impressive technological step but many biologists say that it's overstating the development to call it synthetic life. But their new cell does live. It's replicated now over a billion times. So why are scientists doing this? Well, Dr. Venter says the endeavour began as an effort to understand life on the most intimate level. What he has developed now, he says, are the tools to design new organisms which could mark a new era of biotechnology.

Craig - I think they're going to potentially create a new industrial revolution if we can really get cells to do the production we want, if they could help wean us off off oil, and reverse some of the damage to the environment like capturing back carbon dioxide. I  would be pretty satisfied with that outcome alone. We think some of the earliest applications people will see are new vaccines. We can make, in a day, new flu vaccines that have taken much longer to produce by conventional methods and we're working with the National Institute of Health and Novartis to build the process for very rapidly as new infections emerge to synthetically in 24 hours or less, make those vaccine candidates and get them into testing.

would be pretty satisfied with that outcome alone. We think some of the earliest applications people will see are new vaccines. We can make, in a day, new flu vaccines that have taken much longer to produce by conventional methods and we're working with the National Institute of Health and Novartis to build the process for very rapidly as new infections emerge to synthetically in 24 hours or less, make those vaccine candidates and get them into testing.

Victoria - But these claims too have sparked criticism, not just by scientists who feel the potential of this technology has been overstated but by the wider community. Julian Savulescu an ethics professor from the University of Oxford has said that the potential of this science is - although very far in the future - very real and significant, dealing with pollution and creating the new energy sources that Dr. Venter himself is so enthusiastic about. But as he pointed out, the risks are also unparalleled and this is a very rapidly moving and new field. It seems that the regulatory and safety discussions haven't really kept pace. This technology could be used in the future to make some very powerful bio-weapons. That's a very extreme example, but the potential is there. It's less than 15 years since Dr. Venter first announced that he wanted to create a synthetic organism and we're already at this stage. What concerns many people now is that the pace of this exciting new field of biology should not overtake those ethical and safety discussions. As Professor Savulescu puts it, "The challenge now is to eat the fruit without the worm."

12:01 - BioBlitz in Bristol - engaging the public with nature

BioBlitz in Bristol - engaging the public with nature

Ed Drewitt, Bristol Natural History Museum

Chris - 2010 is the International Year of Biodiversity and a park in the centre of Bristol may not seem the obvious place to study biodiversity. It depends to what you're up to I suppose. But this weekend, Blaise Park has been host to what's known as a BioBlitz which is an attempt to find and catalogue all the different types of wildlife that you might come across. BioBlitzes are going to be happening all over the country in the next few months, so to explain more about what's coming and to hear about what they've done over the weekend, we're joined by Ed Drewitt and he's from the Bristol Natural History Consortium. Hello, Ed.

Ed - Hello, Chris.

Chris - Welcome to the Naked Scientists. Thank you for joining us. First of all, could you tell us what actually is a BioBlitz?

Ed - Yes. Well a BioBlitz is basically an opportunity to bring scientific experts, naturalist  volunteers and the public, schools and families together to basically see and find as many different species that are living in their area as possible. So as you mentioned, in Bristol Blaise Castle Estate and we had lots of schools on a Friday and then families on a Saturday engaging with experts, naturalists and volunteers looking for the different trees, lichens, aquatic insects, birds, and everything else that lives out there.

volunteers and the public, schools and families together to basically see and find as many different species that are living in their area as possible. So as you mentioned, in Bristol Blaise Castle Estate and we had lots of schools on a Friday and then families on a Saturday engaging with experts, naturalists and volunteers looking for the different trees, lichens, aquatic insects, birds, and everything else that lives out there.

Chris - What are you hoping to get out of this? Why do we think this is worth doing?

Ed - Primarily really to sort of engage the public, engage people in different parts of the country - in this case, in Bristol really with what's on their door step and opening people's eyes up to what's actually there. But also, there are some real kind of scientific outputs as well. On the BioBlitz that we had over the last couple of days or so, we found 536 species of which two were nationally scarce and I think not really recorded before including such as the Grass Rivulet Moth for example. And so, it's an opportunity to find out what's there and to then be able to advise the - for example the land manager for Blaise which is owned by Bristol City Council on what's there and what they can do to help some of that wildlife.

A lot of that data then goes, or all of that data then goes to the Bristol Regional Environmental Record Centre and they then put that data into a special database which can be used by members of the public and businesses who perhaps want to then find out what's on there. Particularly for example if there was a building application which is probably not going to happen on this particular place but might happen elsewhere in the country and so we can have a good idea of what's actually living in these places.

Chris - So when people come along to get involved, how will they actually go out and collect the data? Will they be given a 'pooter' - one of those pots with tubes coming out to suck things up or do they go around in little teams? How's the data gathered?

Ed - Well basically, we had families - you might have say, 10 people, it might be 2 or 3  families going out with a naturalist and a couple of volunteers so they might for example be going into some grassland. So they'll take out a couple of sweep nets and some white trays, and ID charts and actually, be doing their own sweep netting and discovering what's in that grassland. Likewise, if they're looking in a stream or a pond, they'd also will be doing that with nets and also using pooters as well to get some of the very tiny insects. And then that information is then put into recording forms which is kind of almost like quality controlled through the naturalist who'll be putting that onto the recording form, and from there, then it gets put on to a natural database. So it's very much about getting the public and schools hands on with nature. So we had school children and families properly doing sweep netting and then really discovering on a small, kind of minute level, what was actually living on their step.

families going out with a naturalist and a couple of volunteers so they might for example be going into some grassland. So they'll take out a couple of sweep nets and some white trays, and ID charts and actually, be doing their own sweep netting and discovering what's in that grassland. Likewise, if they're looking in a stream or a pond, they'd also will be doing that with nets and also using pooters as well to get some of the very tiny insects. And then that information is then put into recording forms which is kind of almost like quality controlled through the naturalist who'll be putting that onto the recording form, and from there, then it gets put on to a natural database. So it's very much about getting the public and schools hands on with nature. So we had school children and families properly doing sweep netting and then really discovering on a small, kind of minute level, what was actually living on their step.

Chris - And what did the scientists and naturalists who you've had involved in this, what do they make of it and are they supportive?

Ed - Absolutely. I think that what we found early on particularly perhaps in previous years and last year when we first sort of started this was scientists and naturalists, being particularly modest about themselves and don't always necessarily see themselves as someone who can offer loads of opportunities. But I think now we've got the balance right of being able to enable and give the confidence to naturalists and other scientists to come forward and realise that they can feel empowered and actually take families or school groups out themselves, and actually engage people with them. So, it's had a very positive output and I think it's really nice where I think people that have enjoyed actually transfering their knowledge and their skills onto people perhaps who wouldn't normally engage or do this sort of thing.

Chris - And it's not just Bristol. This is going to be scaled up or is going to be taken to other cities around the country so we'll have one coming to Cambridge, won't we?

Ed - Absolutely. That's right. So Bristol has been leading on this in terms of being one of the first city to do this this year, linking in with the year of biodiversity and there's going to be lots of other ones over 15 or 16 across the country taking place. And people can find out where they're taking place by visiting the website bioblitzuk.org.uk and as you say, you can find out where things are going to be happening close to you. There's going to be one in Derby, there'd be one that The Natural History Museum are doing down on a coast in Devon for example. So they're going to be happening all across the country and therefore, families, the public, scientists can all engage on a local scale.

Chris - And finally Ed, what do the people who come and take part, members of the public actually make of the experience? Do they think it's just a run around in the grass with their kiddies or do they actually take away the scientific message as well?

Ed - I think people have actually really been engaging. When you're seeing actually getting down to the minute level and wanting to do more, and we had lots of families come back. So we have families for example doing the dawn chorus walk and then they came back later on to perhaps do some stream sampling or doing some insect work. So from what we can tell so far, it's been a very positive engagement with people wanting to come back and do more and hopefully continue with our Bristol Festival of Nature we've got for example in a couple of week's time in June.

Chris - Ed, brilliant. We'll have to leave it there, but thank you very much for joining us.

Ed - Thank you.

Comments

Add a comment