In this NewsFlash, we find out why some astronauts' sight suffers in space, explore the pressure for better prostate cancer screening and discover that nanoparticles may turn bacteria into superbugs! Plus, how your gut learns to tell food from foe..

In this episode

00:24 - Eyes vote no to space travel

Eyes vote no to space travel

Head scans of astronauts have shown signs of raised intracranial pressure affecting their eyes and pituitary glands, new research has revealed...

Writing in the journal Radiology, University of Texas Medical School, Houston radiologist Larry Kramer MRI scanned 27 spacefarers who had each notched up an average of 108 days in orbit.

The imaging showed signs of small cavities in the pituitary glands of three astronauts, flattening of the backs of the eyeballs in six cases, increased fluid around the optic nerves in nine individuals and bulges in the optic discs inside the eye in four cases.

These are features that would normally characterise increased intracranial pressure and they go some way towards explaining the basis for something that NASA has known for a while: that in the aftermath of exposure to microgravity, astronauts have an above-average chance of experiencing vision problems.

In fact, 30% of short-duration space trippers and 60% of longer-duration orbiters report sight loss symptoms.

The researchers speculate that the changes are caused by fluid shifts that occur inside the head in response to chronic microgravity exposure. Fluid that would normally collect in the tissues of the extremeties under the influence of gravity instead builds up inside the head. This is the same reason that astronauts often characteristically become temporarily puffy-faced in space.

But what is intriguing to NASA is not the 60% who do suffer problems but the 40% who don't. Studying them might reveal why they are relatively protected from the problem and lead to ways to protect those at risk, or identify individuals best suited for longer space missions.

Sending someone to Mars is likely to involve a year in space, so solving problems like this will be critical to the success such missions. In the meantime, NASA are proposing to carry out pre- and post-flight MRI scans of their astronauts on Earth and then monitor them in orbit using ultrasound scans of their eyes.

03:39 - Still no clear answers on PSA testing

Still no clear answers on PSA testing

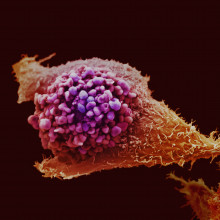

March is widely recognised as prostate cancer awareness month - a disease that affects nearly 40,000 men in the UK every year, and many hundreds of thousands more worldwide. But while we have screening programmes over here for breast, cervical and bowel cancer, we don't have a national screening programme for prostate cancer, even though there is a blood test - the PSA test - which measures the levels of PSA, a protein produced by the prostate gland that can be raised in men with prostate cancer.

The reason for this is because doctors simply don't know how reliable the PSA test is. The problem is that PSA levels can be raised by a number of non-cancerous conditions, so it's not very specific. And there's also a small but significant proportion of men with prostate cancer who don't have raised PSA levels.

And finally, even if a man does have a raised PSA level, and does have prostate cancer, it's hard to know whether it's an aggressive cancer that needs urgent treatment - and along with that comes the risk of serious side effects - or a slow-growing cancer that can be safely monitored over time. But if the test does pick up aggressive cancer at an early stage, it can save a man's life.

And finally, even if a man does have a raised PSA level, and does have prostate cancer, it's hard to know whether it's an aggressive cancer that needs urgent treatment - and along with that comes the risk of serious side effects - or a slow-growing cancer that can be safely monitored over time. But if the test does pick up aggressive cancer at an early stage, it can save a man's life.

Because of this confusion, many research teams around the world have been carrying out large studies to find out whether the benefits of PSA testing across large populations outweigh the risks. But, frustratingly, new results following up a big study of prostate screening don't provide any firm answers.

These are results from the European Randomised Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer - known as the ERSPC - which was set up in 1991 to try and figure out the effectiveness of PSA testing, looking at men in the Netherlands and Belgium, as well as Sweden, Finland, Italy, Spain and Switzerland.

These new results - following up more than 180,000 men after 11 years - have just been published in the New England Journal of Medicine. In the study, the men were divided into two groups - one were given PSA testing roughly once every four years, while the other group were left unscreened - but, of course, were free to go to the doctor if they noticed any unusual symptoms.

The researchers discovered that the death rate from prostate cancer was just over 20 per cent lower in the men who were PSA tested than untested men. But after further calculations, the scientists showed that in order to prevent one death from prostate cancer during the 11-year period, more than 1,055 men would need to be invited for screening, with nearly 40 cancers detected.

This chimes with results from the same study published two years ago. Meanwhile, a similar study in the US has also found that PSA testing has little impact on saving lives from prostate cancer, but may be leading to men being more likely to have treatment causing side effects such as impotence and incontinence for a cancer that may not be aggressive.

At the moment, men in the UK are advised to discuss PSA testing with their GP, who can outline the risks and benefits. But this study - and the others like it around the world - only serve to highlight the problems with the PSA test, and the urgent need to develop better tools for detecting aggressive prostate cancers at an early stage that will save lives, while avoiding men having to go through unnecessary treatment for tumours that are unlikely to be dangerous.

07:26 - How the Intestine Informs the Immune System

How the Intestine Informs the Immune System

Dr Mark Miller, Washington University

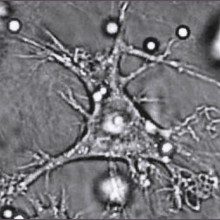

Chris - This week, how the intestine tells harmless food items from potentially harmful bacteria and parasites has been revealed by researchers in the US. Professor Mark Miller at Washington University in St. Louis was using a technique called two-photon imaging to study the intestines of living mice. These animals were special because one class of their immune cells had been made to glow, so they could be seen easily. These are cells called dendritic cells or DCs and they're known as antigen presenting cells because their job is to educate the immune system about what it should attack or ignore. But when Mark then fed these animals samples of sugars that had glowing labels so that he could follow how those food components got moved across the intestinal wall and introduced to the immune cells, he wasn't quite expecting to see quite what he did...

Mark - The surprising finding was that the cell that does this is a highly secretory cell. It's called the goblet cell and its primary function is believed to be secreting mucus that provides a barrier or protection to the epithelial layer. What we found is that these cells, as they secrete, they also allow some of the luminal contents to be transported across the epithelium. So this is different from the process by which you would absorb nutrients or food. It's a way to deliver very concentrated amounts of an antigen to antigen presenting cells, and it's a new function that we've discovered for the goblet cell which has been studied for a very long time.

Chris - Now you looked at one particular tagged antigen. Obviously, it's slightly more complicated when we're eating a balanced diet and there are lots of things coming in. So, have you got any idea as to whether or not those goblet cells discriminate between the good guys and the things we want to educate our immune system to ignore, and the bad stuff that we actually want the immune system to attack or do those goblet cells transfer everything and the immune system makes that decision?

Chris - Now you looked at one particular tagged antigen. Obviously, it's slightly more complicated when we're eating a balanced diet and there are lots of things coming in. So, have you got any idea as to whether or not those goblet cells discriminate between the good guys and the things we want to educate our immune system to ignore, and the bad stuff that we actually want the immune system to attack or do those goblet cells transfer everything and the immune system makes that decision?

Mark - That's a fascinating question. What we think is that their transporting mostly small soluble peptides, so these can be parts of a protein or intact proteins. It can also be things like sugars, so we're using dextran as one of our model antigens. So I think if there's any discrimination, it's that it would prevent something large like maybe an intact bacterium from getting across but allow these small soluble antigens to actually get across. But on the other hand, once the antigen comes across the epithelium, the antigen presenting cells themselves have specific receptors to take up sugars or certain proteins. So, even if there's a lack of specificity at the goblet cell step, the dendritic cell itself will be better at taking up certain substances and that could also lead to a different outcome in terms of an immune response.

Chris - If I have a healthy gut and I'm just presenting normal food stuffs then I can understand that being an absolutely perfect mechanism. But what about when I get a dose of Delhi belly or Montezuma's revenge, I get bacteria there that I shouldn't have or an overgrowth of even a parasite. Surely, there will then be antigens going across the wall of the gut. How do you stop the immune system saying these are friendly? How do you make the immune system on that occasion decide to attack that foreign antigen?

Mark - It's interesting that we've seen that this function of goblet cells appears to be downregulated when you have a pathogenic infection, so it's as if the barrier, the mucosal barrier, tightens up. So that's one response, but the fact that the antigen is coming in with a pathogenic organism will cause inflammation, pathogen associated molecular patterns will stimulate dendritic cells in such a way that they promote an inflammatory immune response. So again, that would happen at the level of the dendritic cell.

Chris - And what about in allergy states and other disease states? We know that there's an association if you give very young kids big doses of broad spectrum antibiotics that clear out lots of the bacteria that should be there then they're much more likely to develop allergy and diarrheal states later in life. Have you got any clues from the mechanism you've spotted how that sort of thing might actually be manifest and why it happens?

Mark - Yes, we do. So for example in the paper, we used germ-free mice that lack the normal flora that would colonise the small intestine. And in that case, we saw quite a lot of antigen being transported across. So, that experiment is showing that the normal flora or the bacteria in the gut may very well regulate this process. So depending on what species of bacteria are present or whether or not it's pathogenic or non-pathogenic, that could tie in very closely with how much of that antigen is delivered across the epithelium and change the character of the subsequent immune response.

Chris - And are you in a position now to manipulate this system? Do you understand what the trafficking system is, so that you can go in and intervene, and stop things that might provoke an allergy or indeed in someone who has an established allergy, stop it presenting itself to the immune system, so that person's allergy goes away?

Mark - We are definitely working in that direction. It turns out that we think this transport function is directly related to goblet cell secretion. And of course, we have both agonists and antagonists to either induce secretion or inhibit secretion. So, we are looking in various models right now to see how either shutting down this goblet cell mediated antigen transport or upregulating it may affect outcomes in models of inflammatory bowel disease for example.

13:07 - Nanoparticles turn bacteria into superbugs

Nanoparticles turn bacteria into superbugs

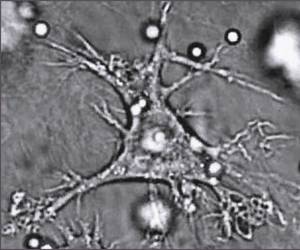

Nanoparticles used routinely in wastewater cleanups can encourage bacteria to breed superbugs, new research has shown. The findings could have major implications for the way in which sewage should be processed in order to prevent the appearance of bacteria equipped to resist every known antibiotic.

Writing in PNAS, Institute of Health and Environmental Medicine scientist Zhigang Qiu and his colleagues measured the amount of gene-swapping taking place between bacteria incubated with a range of common industrially-employed nano-particles. Alumina (Al2O3), titanium dioxide (TiO2), silicon dioxide (SiO2) and iron oxide (Fe2O3) were tested. All of them promoted the exchange amongst the bacteria of a test DNA plasmid called RP4, with alumina particles producing the largest effect - up to a 200-fold increase in the rate of successful DNA exchange compared with bugs grown without nanoparticles.

Writing in PNAS, Institute of Health and Environmental Medicine scientist Zhigang Qiu and his colleagues measured the amount of gene-swapping taking place between bacteria incubated with a range of common industrially-employed nano-particles. Alumina (Al2O3), titanium dioxide (TiO2), silicon dioxide (SiO2) and iron oxide (Fe2O3) were tested. All of them promoted the exchange amongst the bacteria of a test DNA plasmid called RP4, with alumina particles producing the largest effect - up to a 200-fold increase in the rate of successful DNA exchange compared with bugs grown without nanoparticles.

The gene transfers were also not limited to bugs of the same species. Mixtures of E. coli and Salmonella bacteria also increased their rates of gene swapping in the presence of the nanoparticles. The effect appears to be the result of biochemical stress. Electron microscope images show that the nanoparticles damage the bacterial cells, activating a range of protective responses, including a preponderance to swap sequences of genetic material.

Worryingly, the concentrations of nanoparticles needed to achieve this (about 2 million per millilitre) are much lower than those presently used industrially to scrub heavy metals and other contaminants from waste water. So present processing practices could be encouraging bacteria that harbour antibiotic-resistance genes to disseminate their dangerous DNA cargo.

15:33 - Predicting how drugs interact and driving flies to drink

Predicting how drugs interact and driving flies to drink

Predicting how drugs interact to produce side effects

Scientists have come up with a new way to anticipate previously hard to predict drug side effects. During their development, most drugs are tested in isolation, meaning a patient only takes one drug at one time. But, in the clinic, most patients end up being prescribed mixtures of different drugs at once to treat a range of diseases. And predicting how these mixtures might lead to side effects has always been extremely difficult. But now, writing in Science Translational Medicine, researchers at Stanford University have used data from four million patients to design a statistical system that can spot when potential problems might arise, including between combinations of drugs in routine current use.

Nicholas Tattonetti - We identified a potential interaction between thiazides that treat hypertension and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors which are antidepressants, and we associated them with an increased prolonged QT interval and this is a clinical risk factor for heart arrhythmia. So it's a potentially important clinical variable.

Tatonetti NP et al (2012), Sci Transl Med, 4, 125, Data-Driven Prediction of Drug Effects and Interactions

A new uranium compound has been produced which could help mop up nuclear waste

A new form of uranium could make radioactive waste easier to reprocess in the future. Generating electricity from nuclear power inevitably produces radioactive materials that need recycling or long term storage. At the moment the estimated cost of clearing up just the UK's accumulating stock of nuclear waste is 70 billion Pounds. But now, Edinburgh University chemist Polly Arnold and her colleagues, writing in the journal Nature Chemistry, have discovered a new way to make clusters of uranium which may make these valuable radioactive materials easier to recycle.

Polly Arnold - One of the things that happens when you process nuclear waste is you need to separate out all the different metal components, the metal oxides. Things that can cause problems is when they cluster and form aggregates. But people don't know very much about how these form and then how to get rid of them. So the fact that we've seen this tiny beginning of a cluster suggests that it might lead us to think about new ways the clusters might form and then new ways to deal with the nuclear waste processing that goes on at the moment.

Arnold PL et al (2012), Nature Chemistry, 4, 221-227, Strongly coupled binuclear uranium-oxo complexes from uranyl oxo rearrangement and reductive silylation

Treating manic depression by increasing the strength and length of the body clock

Scientists have uncovered how the drug lithium, which can help sufferers of bipolar disorder, or manic depression, as it is also known, actually works. Lithium has been one of the main treatments for bipolar disorder for the last 60 years. But exactly how it works has remained a mystery. Now, writing in PloS One and using cells cultured from mice, scientists have shown that lithium achieves its therapeutic effects by strengthening the body's circadian clock, which it does by switching off a signalling enzyme called glycogen Synthase Kinase 3 beta. In people with mood disorders this enzyme has been shown to be overactive. The discovery could have implications for other neurological disorders.

Jian Li et al., (2012) PloS One Lithium Impacts on the Amplitude and Period of the Molecular Circadian Clockwork. e33292. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0033292

Fruit flies deprived of sex turn to alcohol

Flies deprived of sex turn to alcohol, scientists have shown this week. One group of male flies were offered multiple mating opportunities. A second group were repeatedly rejected by a group of already sexually satisfied females. Provided with a choice of foods that either did or didn't contain alcohol, the flies that had been repeatedly rejected were much more likely to opt for the booze soaked dish.

Galit Ophir - This is a basic science study so it tells us better about how the brain represents social experience in terms of reward and it has implications into understanding better the mechanisms that are involved in social reward which is important to social related disorders and also to addiction. That study was published in the journal Science.

G. Shohat-Ophir, et al., (2012) Science, 335, 6074: 1351-1355. Sexual Deprivation Increases Ethanol Intake in Drosophila.

Comments

Add a comment