In a special festive edition of Naked Oceans we count down the 12 critters of Christmas. Packed into our seasonal critter fest are sea angels and Christmas tree worms, cuddly marine mammals and less-cuddly deep sea fish. We'll meet an ocean migrant that could lend Father Christmas a helping hand and we'll venture into the deep sea to track down a fish that glows as brightly as Rudolf's nose.

In this episode

01:35 - Sea Angels

Sea Angels

with Rob Jennings, University of Massachusetts

Sea snails that have lost their shells and flap their wings through open ocean and found some interesting ways to stop themselves becoming someone else's dinner, as Rob Jennings, from the University of Massachusetts, explains...

Rob - So sea angels are a group of snails, basically. They're not too distant relatives of garden snails that you would find on land in your back yard.

Sea angels have evolved the behaviour of living in the water column. They're born swimming in the ocean, they grow up swimming in the ocean, and they spend all of their lives in the middle of the water never touching the bottom.

They are very beautiful animals. You know, they have these transparent bodies and these giant wings, they look a lot like angels. In a marine world where we've named things sea slugs, and we have sea lice, and we even have sea cucumbers I think it speaks to how beautiful they are that they've inspired the name sea angels.

As far as we know right now it looks like the marine snails that live on the bottom that have that normal sort of snail shell were the first kind to evolve and then they evolved so that they could live up in the water column but they brought their shell with them.

And over a lot of evolutionary time, there's evolution to loose this shell so sea angels are sort of the result of this evolution - these snail-like molluscs but without a shell anymore.

But one of the really interesting things is that in Antarctic waters Clione antarctica has developed this evolutionary tactic to sort of make up for the fact that it doesn't have a shell.

So, if you're swimming in the water column a shell is heavy, and it sort of pulls you down, but it also offers you protection, so you can retreat into your shell then it's very hard for anyone to eat you.

So these sea angels have lost that protective ability, but instead they've evolved, or at least Clione Antarctica has evolved bad tasting compounds that it synthesises. So, fish and other predators learn very quickly when they take a bite of Clione that it's not something that they want for a meal.

And this has led to actually a very curious interaction between sea angels and a totally unrelated group of animals, hyperiid amphipods, they're sort of distant cousins of shrimp and of krill.

And these amphipods have learned that if they grab onto a Clione and essentially hold is hostage and swim around carrying this giant sea angel on it's back, that fish and other predators won't eat the amphipod because it's got this bad-tasting Clione carried along with it.

So they sort of abduct Cliones and use them as protection and then will let them go after a time so the Clione can feed and stay alive itself, and then grab another Clione as soon as they can.

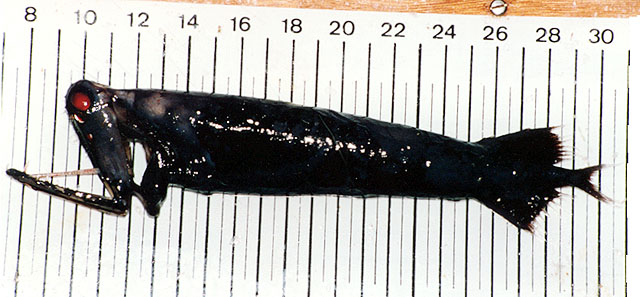

04:37 - Glowing red fish light up the deep sea

Glowing red fish light up the deep sea

with James Maclaine, Natural History Museum

Stop light loose jaws bright red glow lets them see more that the average deep sea fish.

Find out more:

Find out more:

Stop Light Loose Jaw at the Natural History Museum.

James - My name is James Maclaine and I work as a curator at the Natural History Museum in London. And I've seen many, many weird and wonderful fish, but one of my favourites is a thing called the stop light loose jaw, which is a deep sea fish and it has some very unusual abilities.

It's found all round the world in all the main oceans, the Pacific and the Atlantic, and it like many of the fish living at depths like that is capable of producing light. It has two different lights on its head, one behinds its eye and one a bit further back behind its jaw.

And one of these is blue, which is not unusual, a lot of the fish and other organisms at that depth use blue light because it travels quite far through the water, it travels further than any other kind of light.

But the really unusual thing about the stop light loose jaw is that it also has a read light and it's one of only three kinds of fish that can do this.

And the unusual thing about it is that hardly anything else can see it, everything's eyes are tuned to blue light. So the red light that's produced by the stop light loose jaw is pretty much invisible. So it has its own private wavelength of light.

And we're still not totally sure what it uses it for. It could use it like a torch, to sort of, shine ahead of it as it's swimming around looking for prey. Or it could even use it to communicate with other stop light loose jaws and of course everything else would be oblivious.

The thing I really like about it is just its really fearsome appearance. I can remember as a small boy seeing pictures of deep sea fish the stop light loose jaw in books and just thinking these, maybe huge monsters living in the bottom of the sea and only recently I found out that they're, you know, pretty tiny compared to a lot of the other things that people know about lie sharks and things - they're fairly small.

But yeah, they look like nightmarish creatures. They have these big huge fangs and they're very weird looking. So, I think that's one of the things that appeals to me about it. And I quite like the mystery of it. Although we can make educated guesses about what it's doing with its light, we're not 100% sure and we may never be because it's very, very hard to go down to that depth and watch these things behaving naturally.

So it could be doing things with it's lights that we just would never have dreamt of.

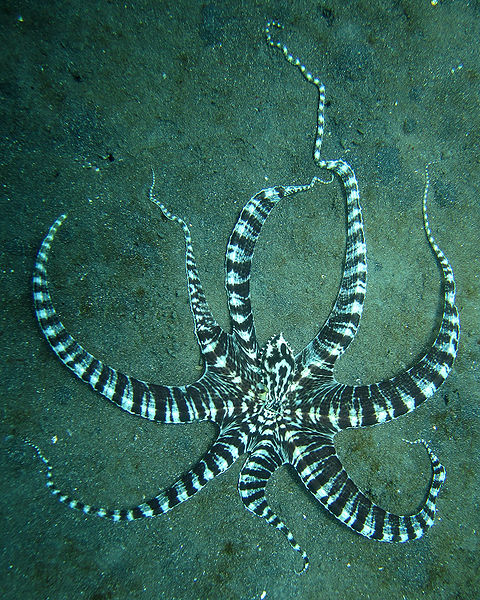

07:16 - Masters of disguise

Masters of disguise

Does the mimic octopus have a split personality or does it just like dressing up?

Find out more:

Find out more:

The evolution of conspicuous facultative mimicry in octopuses: an example of secondary adaptation?

Helen - But first, I've got one of my personal favourites. These guys aren't especially Christmassy, but they have an eye-popping repertoire of party tricks up their tentacles, and I think they'd definitely be fun to have around. So, my choice for Christmas critter number three is the mimic Octopus.

They were discovered in 1998 in Indonesia where they live in sandy silty areas around river mouths. And they've been caught on camera putting on an extraordinary range of impersonations of other animals.

They will stick all but two of their arms down a hole, then make the other two stripy and wave them around like a sea snake. They can lay their arms out flat and swim across the seabed like a flat fish. They wave their arms over their heads to look like a lionfish. And it's thought they can also do impressions of anemones, sting rays, mantis shrimp, and even jellyfish.

Sarah - It's pretty spectacular stuff, but do we have any idea why they do it?

Helen - Well, scaring off and confusing predators seems to be the most likely explanation because lots of the creatures they mimic are poisonous - so they can pretend to be dangerous by co-opting the fearsome reputation of others. And that's something that lots of other animals do, like non-stinging bees that have evolved yellow and black stripes to look like wasps.

But the thing about the mimic octopus it's the only animal that we know of that mimics a wide range of other animals and can switch between them minute by minute. And this means they can tailor their impersonations depending on what is threatening them at any particular time.

A recent study has looked into how the mimic octopus evolved just one of its clever tricks - the flatfish impersonation. Researchers found that this is a combination of first evolving the ability to change colour quickly - this confuses predators, almost like shouting at them with colour, which is something that many octopus species do. Then the mimic octopus ancestors evolved long arms and figured out at the same time how to wrap them around themselves, squash themselves flat and swim above the seabed like a flat fish. Combine that with the colourful display, and they put on an uncanny impression of a venomous flatfish.

So, Paul the Octopus may have become a worldwide celebrity for his weird football predicting skills, but there are some other even more surprising talents to be found in the rest of the octopus world.

10:00 - Sirens of the sea

Sirens of the sea

We meet the dugongs and manatees, those mysterious marine mammals that were once mistaken for mermaids.

Find out more:

Find out more:

West Indian Manatee, at the Florida Museum of Natural History

Sarah - Well, we've reached our Christmas critter number four, and I've chosen some gentle giants. The dugongs, and their close cousins the manatees.

These are the sirenians, a group of marine mammals that evolved from four legged ancestors that took to the sea around 50 million years ago and supposedly were mistaken by sailors for mermaids... hmmm... not sure about that, maybe they'd been at sea for way too long.

well, they have a host of adaptations to an aquatic life - they have very dense bones that act as ballast, and huge lungs that take up two thirds of their body length, which they use to control their buoyancy.

And they've earned themselves a reputation as the dummies of the marine mammal world, because their brains are only the size of a cricket ball - which in actual fact is probably an unfair label, because they can be trained to perform similar tasks as their more famously intelligent cousins, the dolphins.

It might be not so much that dugongs and manatees have tiny brains but that they have evolved super-sized bodies that keep them warm and provide enough space for a huge stomach to digest all the tough seagrass and vegetation they eat.

There are four living sirenian species - a single dugong species lives in the Indian and Pacific Oceans, there's the west African manatee, and the west Indian manatee that lives around the Caribbean, plus a third species that's evolved to tolerate freshwater in the Amazon river.

But there have been lots more sirenian species in the past - there are around 50 extinct fossil species known of, and one of the biggest was the Stellar's Sea cow. That one grew to a gigantic 8 metres in length and used to live across the North Pacific until people hunted them to extinction because they were just too tasty and being such slow, docile creatures they were too easy to catch.

Helen - And I guess not many people hunt manatees and dugongs today, but they do face various threats still, don't they?

Sarah - Yep, there are problems like getting hit by boats as well as habitat loss - they eat a lot of seagrass and other vegetation that's under threat globally. And then last winter, a lot of manatees in Florida died because the temperature plummeted - seems they are sensitive creatures.

And Helen, do you know how to tell the difference between a dugong and a manatee?

Helen - It's their tails isn't it?

Sarah - Yeah, that's right - Manatees have a spoon shaped tail, while Dugongs have fluked tails more like a dolphin.

12:39 - Champion migrant

Champion migrant

with Richard Phillips, British Antarctic Survey

Arctic terns are global champions flying from the South Pole to the North Pole and back every year. Perhaps they could give Father Christmas a hand delivering all those presents?

Find out more

The Arctic Tern Migration Project

Richard - The arctic tern is a small seabird, weighs something like 100-120g, and it breeds all throughout the North Atlantic on little islands off and occasionally on main lands.

For such a small species they travel vast distances. They make the longest migration of any animal on the planet, all the way from the north to the south pole and back again.

So in total, during the non-breeding period arctic terns travel upwards of 80 thousand km per year.

Essentially the arctic tern tracks and endless summer exploiting the productive waters around the breeding colony in the northern summer and then moving down into the Antarctic for the summer there to exploit the high krill abundance.

We track them using geolocators which are little loggers than you put on the bird's leg that record light and from them you can derive the time of sunset and sunrise and suing astronomical algorithms you can derive latitude from day length and longitude form the time of local noon.

Although arctic terns don't interact with any major fisheries the problems they face are probably those due to natural reductions in food supply as a result of global warming.

For example there's been a decadal decline in Antarctic krill abundance and that has almost certainly had knock on effects on the terns.

So far their breeding populations seem to be stable but with continuing krill decline means we don't know what's going to happen in the future.

Arctic terns are not unique in terms of being trans hemispheric migrants, there are a few other sea birds that follow similar sorts of routes although they don't tend to go as far south as the arctic terns. But also these routes, interestingly enough, are also those that the clippers ships used during the great trading days of the nineteenth century.

14:52 - Fastest claws in town

Fastest claws in town

Mantis shrimp have a lightening fast punch and the most complex eyes in the animal kingdom.

Sarah - For our 6th Xmas critter we're going to be venturing out to the tropical coral reefs for one of my personal favourite species, which is the mantis shrimp.

These are like the Kung Fu masters of the ocean world. They're found all around the world in both tropical and subtropical seas.

These are like the Kung Fu masters of the ocean world. They're found all around the world in both tropical and subtropical seas.

They range from only just a few cms, so a couple of inches long, up to around 30cm, which is about 12 inches. And they can shoot out their front claws which are either shaped like spears or clubs, which is why they earned the names mantis shrimps because they look a little bit like preying mantises - and they can shoot those out at around 23m/s with an acceleration of over 100,000 m/s2, which is equivalent to the speed of a speeding bullet.

And they also have the most elaborate and complex eyes of any animal on the planet.

So let's start with their claws. Different species use their claws in different ways. Some have these barbed, spearing claws to jab out a soft prey like fish. And others have club-like claws that they use to break open harder prey like snails and crabs.

These claws shoot out from the mantis shrimp so fast that they actually create little collapsing bubbles that make a pop like a small sonic boom. And they can even sometimes produce a tiny bit of light as the energy produced is so high.

The shock wave created by the bubbles collapsing is actually enough o stun the prey so even if they don't hit it with their claws they can still get it afterwards.

Not that they would be likely to miss their prey with their claws because of their incredible sense of vision.

Like other arthropods including other crustaceans like crabs and lobsters as well as insects and spiders, mantis shrimps have compound eyes.

These are made up of lots of tiny little eyes called omatidia, each with its own lens and light and colour-sensing pigments.

We have 4 different types of photoreceptor pigments in our eyes. One type in the rod cells that senses the brightness of light, and 3 types in the cones that detect different wavelengths of coloured light.

Mantis shrimps have 16 different types of pigments. They can see infra red, and ultra violet light as well as polarized light. And the position of their eyes on movable stalks also means they have accurate depth perception. Obviously very useful for aiming your strikes at your prey.

So, although they're quite small, those mantis shrimps, you certainly wouldn't want to mess with them.

Another name for them is thumb splitters because they can give a nasty injury if you get them annoyed.

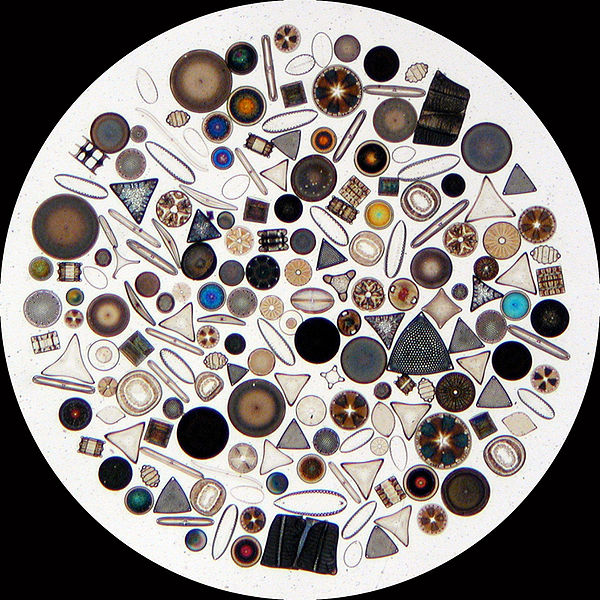

17:55 - Does it snow in the sea?

Does it snow in the sea?

with Kate Hendry, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute

Diatoms are the gems of the ocean that lock up carbon and are vital for all sorts of other creatures from krill to penguins.

Find out more:

Find out more:

Diatoms at the Tree of Life.

Kate - Diatoms are a kind of microscopic algae. So they're a bit like plants, they can photosynthesize which means they can use the energy in sunlight to fix carbon, carbon dioxide from the atmosphere into their food, into their carbohydrates and sugars.

And they grow in the surface of the ocean but they can grow pretty much anywhere. They live in rivers in lakes and puddles, pretty much anywhere you look.

They make their shells out of silica or sort of glass like substance and there shells are really very beautiful, very intricate designs. They can be pillbox shapes, needles or even stars.

So although they're really small, diatoms when they grow together form big clumps. They produce this sticky substance that makes them stick together in big mats. And this means that when they die they can sink really quickly and these big clump mats can fall out of the surface ocean to the sediments. And because they do this they're sometimes known as marine snow.

An because of this, because they sink very quickly, they're really important for taking carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere, so when they photosynthesize and lock up all this carbon into their shells, when they sink they can transport this carbon from the surface to the sediments and there it can be locked away.

We've already noticed however changes in the different types of algae growing in different regions in response to climate change.

So for example in the West Antarctic Peninsular, we're actually seeing in recent decades a change from populations dominated by large diatoms to those dominated by a different type of plankton called salps.

And not only has this changed how carbon is taken up in this area but it's also had knock on effects for the ecology. So not only is this impacting organisms like fish and krill that live off diatoms but also organisms higher up the food chain like penguins and seals.

So, I think that although that they're tiny organisms, diatoms are some of the most beautiful creatures in the sea and they're also really important both for local ecology and for global climate.

20:13 - Anyone for turkey?

Anyone for turkey?

Should turkey fish - also known as lion fish - be on the Christmas menu?

Find out more:

Find out more:

Invasive lionfish in the Florida Keys (NOAA)

Helen - Well, from one elegant creature that you need a microscope to appreciate to another stunner that can easily be seen with the naked eye.

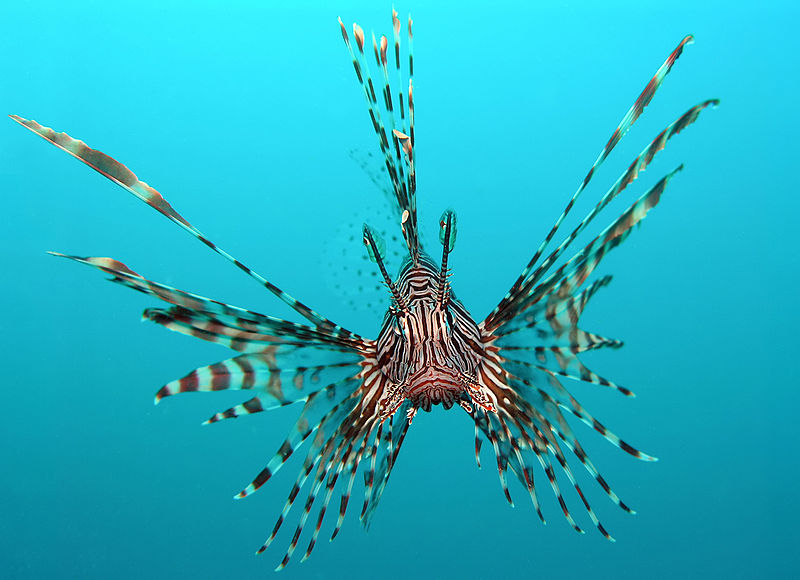

My next critter has a slightly tenuous connection to the festive season, but it's sometimes called the Turkey fish - it's also known as the firefish, scorpion fish, but probably it's most well know as the lionfish.

These beautiful, graceful denizens of coral reefs are quite easy to spot, they tend to be covered in red and white stripes and they dress themselves in a costume of long white spines that stick out in all directions, which you should steer clear of because each spine is tipped with a dose of nasty poison -although they tend not to be deadly for people, but they are extremely painful, and lionfish use them as a means of defence.

Well, originally lionfish lived only in the Indian and Pacific Oceans, but around a decade ago, divers started spotting them a long way from home, in the Caribbean where it's thought they were accidentally - or maybe even deliberately released from aquariums - and they're now spreading throughout the region, stirring up controversy and altering the balance of ecosystems.

Because the problem is, that lionfish may be pretty to look at, but they are also voracious predators. One study revealed that after five weeks, lionfish can munch their way through 80% of the native young fish on a Caribbean reef. And a big worry is that in the Caribbean, lionfish have escaped the natural checks and balances, those predators, parasites, and diseases that in the Indo-Pacific prevent them from taking over. So we really could be facing a lionfish plague.

Sarah - So, what's being done to try and deal with this invasion of lionfish?

Helen - Well, a lot of divers are going out and collecting lionfish by hand - well, with spears and nets - and there are early response networks being set up, so that anyone who spots a lionfish can report it and a swot team of lionfish disposers can be on the scene to quickly whisk it away.

And people have started to work out they are also quite good to eat too... so maybe turkey fish should be on the Christmas menu.

22:29 - Strange string jellies

Strange string jellies

with Gill Mapstone, Natural History Museum

Siphonophores or string jellies are another group of little known but beautiful deep sea critters.

Find out more:

Agalma elegans - a string jelly - at the Natural History Museum

Gill - My name is Gill Mapstone and I'm a scientific associate at the Natural History Museum in London. And I work on some rather unusual animals there, which are called siphonophores.

These are marine creatures which live mostly in the deep sea and often they are actually called string jellyfish or string jellies because they tend to look a bit like a string.

So they have a number of swimming bells at one end and these all pump together to push the animal forward by jet propulsion in a certain direction. And behind that you have more stem with serially reproduced mouths each with a tentacle and usually there's some sort of flotation structures called bracts which look a little bit like leaves. And also the reproductive organs in there.

So, this part of the stem can actually go on for metres in some larger jellyfish. I think one of the largest siphonophores ever found was about 50 m long.

And, I'm interested in them because they are important predators in the sea. They eat a lot of fish larvae and things like that, which are of course important for humans. And also they're quite remote and difficult to access and if you can see them life from the submersible then they look really beautiful.

So, would you know any siphonophores if you saw them? Well, there is one that you probably have heard of but this is not actual typical at all of the group, and that is the Portuguese man of war, who's Latin name is Physalia.

It's very unusual because it's got a big float, it floats on the surface of the sea. Very few things can eat them, although actually turtles can. But they are pretty difficult to study because they're so venomous. And you don't really want to get entangled with one when you're swimming because they can have long tentacle which stretch underwater for some distance.

And these can actually give you a very nasty sting and leave scars on your body. And if you're actually rather ill before you get a sting maybe, or predisposed to some problem, health problems, then you could actually be killed by one of those although that rarely happens.

So that's the Portuguese man of war. Still we don't really know how many species there are in the sea. At the moment we think there's one but there may be another one because off Australia you get a smaller one called the blue bottle.

Anyway they are interesting animals, but the ones that I study are really more beautiful, I would say, and they live in deep water so they are really rather mysterious.

So actually they are really the most fascinating group of animals.

28:52 - Extreme worms

Extreme worms

Giant tube worms cope with many extremes in their homes on deep ocean black smokers.

Sarah - One of my all-time favourite species in the whole ocean is a kind of deep sea tube worm called Riftia.

They live at the deep sea vents in the middle of the Pacific ocean which can be up to several miles below the sea surface. They look a bit like giant lip sticks. They can grow up to 3m long, and they have this hard white outer tube and this beautiful bright red plume sticking out.

They live at the deep sea vents in the middle of the Pacific ocean which can be up to several miles below the sea surface. They look a bit like giant lip sticks. They can grow up to 3m long, and they have this hard white outer tube and this beautiful bright red plume sticking out.

And they're actually an evolutionarily ancient lineage because there are examples in the fossil record dating back to at least the Cambrian which is over 500 million years ago.

The thing that I think makes Riftia special is that its got so many amazing adaptations to living in what we would think of as a really inhospitable environment down there at these hydrothermal vents. There's such high concentrations of toxic nitrates, hydrogen sulphides and really high heat levels.

First of all, let's think about how they get their energy. Down at this depth there's no sunlight so there's no photosynthesis which is how most food chains elsewhere in the oceans begins, which photosynthesizing species like algae and phytoplankton using sunlight to make sugars. So how do Riftia survive?

They have a symbiotic relationship with a type of bacteria that can convert the chemicals spewing out of these black smokers like HS into organic molecules that provide energy for the worms by a process called chemosynthesis.

The worms them absorb these nutrients directly into their tissues so technically they don't actually eat anything which is actually quite an unsual thing for an animal, not to eat, it's able to absorb its nutrients, especially for something that size.

The worms also have a high tolerance for concentrations of sulphides and nitrates that would be deadly to most other animals. The deep rich red colour of their plumes comes from haemoglobin which is the same sort of molecule that makes our blood red but their haemoglobin is differently structured and it's able to withstand high levels of sulphide still allowing it to carry oxygen around the worms body.

They're also the fastest growing marine invertebrate. They can grow nearly 2m in less than 2 years.

But because they live at such depth there's not that much known about them and it means that there's always more being discovered about them.

31:17 - Christmas tree worms

Christmas tree worms

Perfect miniature Christmas trees round off our choice of festive critters.

Find out more:

Find out more:

Does Spirobranchus giganteus protect host Porites from predation by Acanthaster planci: predator pressure as a mechanism of coevolution (PDF)

Helen - Well, that brings us to our twelfth and final critter of Christmas. And how could I resist finishing with another group of great festive beasties - the Christmas tree Worm.

These critters really do look like titchy, one-inch Christmas trees and they've been one of my favourites for ages - you might have spotted them while scuba diving or snorkelling on a coral reef with their frilly crowns decorating boulders of live coral.

They're a type of polychaete worm called a serpulid, and the bit you see sticking out is just their spiralling feathery head gear - a pair of appendages called radioles which they use to sift food and oxygen from the water.

The rest of their body stays safely inside a calcium carbonate tube inside the living coral - when they sense movement around them they quickly flip their radioles back in, and shut the tube tightly shut with another specially adapted radiole called an operculum.

There are two subspecies of Christmas tree worm, one from the indo-pacific and other from the atlantic and the Caribbean, and they come in all sorts of colours morphs - blue, red, orange, yellow, but the most common is white - appropriately enough for a snowy, seasonal critter.

As well as looking pretty, one study has suggested that Christmas tree worms play an important role in coral reefs by protecting living corals from attacks by crown-of-thorns starfish, which don't like being tickled on their sensitive undersides.

And apparently, they can live for up to 40 years. Not bad for a little worm.

Comments

Add a comment