Join us as we venture beneath the waves to uncover alternatives to overfishing. We find out what lies behind the Marine Stewardship Council's blue eco-label for sustainable seafood and talk manta ray ecotourism with Andrea Marshall, "Queen of Mantas". Continuing our look at protecting the oceans, we catch up with Coral Cay Conservation in the Philippines to find out how they've been working with coastal communities to help them protect their local piece of sea and set up fish sanctuaries. And in Critter of the Month we meet a bird that lives above, on, and even in the ocean.

In this episode

01:24 - Drifting fish larvae make MPAs work

Drifting fish larvae make MPAs work

A new study shows for the first time that Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) can benefit surrounding areas of sea by supplying fish larvae that drift out and re-seed areas over 100 miles away. Scientists found this out using a brand new DNA fingerprinting technique similar to forensic technologies used in human crime cases.

The drifting of larvae out of MPAs is a really important plus side for them, but it's something that until now we've had to assume because there's been little direct evidence to show that it actually happens.

Mark Christie from Oregon State university led a team who studied a beautiful reef fish called a Yellow Tang. These fish were in serious decline in Hawaii a decade ago because they were taken in huge numbers for the aquarium trade, until 9 MPAs were set up to help protect them.

Mark Christie from Oregon State university led a team who studied a beautiful reef fish called a Yellow Tang. These fish were in serious decline in Hawaii a decade ago because they were taken in huge numbers for the aquarium trade, until 9 MPAs were set up to help protect them.

Yellow Tang are perfect for studying how fish larvae disperse because once they settle down on a reef they stay put, living within a half-mile home range. So, if a juvenile ends up a long way from its parents, the only way it could have got there is by drifting as a tiny larvae, not by swimming when it was older.

The researchers analysed the genetics of over 1000 juvenile and adult fish in Hawaii and using this new fingerprinting technique matched up offspring to their parents, uncovering that a few young fish ended up on a different reef up to 114 miles from mum and dad. And where they ended up corresponded to with a prevailing northward ocean current.

This is just one species of fish, and there will be many different things going on within a whole ecosystem. But this sort of detailed information is vitally important for the creation of effective marine protected areas, because it helps us to work out where best to put MPAs to maximise the connections between different sites. This should also help encourage ocean users to support MPAs and stick to the rules of not fishing inside them, the idea being that fisheries beyond the MPA can benefit too as well as fish inside the reserve.

As the authors write in their paper, in the journal Plos One, it goes to show the important linkages between different areas of the sea, and that management in one part of the ocean affects people who use the sea elsewhere.

Find out more

Mark Christie et al. (2010). Larval Connectivity in an Effective Network of Marine Protected Areas .

PLoS ONE

Yellow Tang (Zebrasoma flavescens) on

Fishbase

03:56 - How to make a sustainable fishery

How to make a sustainable fishery

Researchers publishing in Nature have described the factors that make for a successful and sustainable fishery. It's the first study to pull together data from papers and NGOs to come up with an idea of what is important in making certain fisheries more successful than others.

At the moment, around a third of all the world's fisheries are overexploited, but a huge number of people rely on fish as their main source of protein, particularly in the developing world. How to extract enough fish to make a fishery economically viable whilst at the same time not overexploiting it is a big challenge.

At the moment, around a third of all the world's fisheries are overexploited, but a huge number of people rely on fish as their main source of protein, particularly in the developing world. How to extract enough fish to make a fishery economically viable whilst at the same time not overexploiting it is a big challenge.

Nicolás Gutierrez and his colleagues from the University of Washington in Seattle looked at 130 co-managed fisheries, which means they are cooperatively managed by communities, managers and scientists, spread around the world.

They looked at what combinations of certain attributes made the fisheries successful, or not. These attributes were things like if there was strong social cohesion in the community managing the fishery, if there were protected areas, what type of fishery it was, the strength of the leadership behind the management of the fishery and so on. The attributes were then correlated with the 'success score' of the fishery, which was calculated by looking at factors like catch abundance and social and economic impacts of each fishery.

What they found was that the most important attribute for the success of a fishery was strong management leadership, followed by the presence of catch quotas, then the level of community cohesion and having protected areas.

Unsurprisingly, they also found that a fishery was more likely to be successful if it had more than 8 of the attributes present.

So, the study offers real hope for the sustainable future of fisheries - which, with the growing human population, is a very good thing.

Find out more

Nicolás L. Gutiérrez et al. (2011). Leadership, social capital and incentives promote successful fisheries.

Nature.

06:57 - Eco-labelling for sustainable seafood

Eco-labelling for sustainable seafood

with Maylynn Nunn, Marine Stewardship Council

Maylynn - The Marine Stewardship Council came to be about 10 years ago and it was put together by WWF and Unilever as a partnership because there was a realisation that what was missing for ocean conservation was a market-based tool, basically an incentive to reward fisheries that are operating sustainably and to create an incentive for those that weren't to raise the bar.

Helen - How do you understand and, almost, define that sustainability.

Maylynn - For the Marine Stewardship Council we have a very objective science-based way of defining sustainability. So, the MSC was set up as an environmental voluntary standard for sustainability so the focus is on the environmental side of things.

Maylynn - For the Marine Stewardship Council we have a very objective science-based way of defining sustainability. So, the MSC was set up as an environmental voluntary standard for sustainability so the focus is on the environmental side of things.

And there are three overarching principles to the standard. The first one focuses on the status of the stock itself, so the assessment teams need to make sure that a stock is healthy, that a stock is doing well.

The second principle is on ecosystems, so looking at habitats and interactions with bycatch species and things like that. So, wider than the stock, also looking at the impacts on the ecosystem.

The third principle is about the legislative framework. So regulation, whether there's proper regulation in place and if it all fits together to support a sustainable fishery.

Helen - Getting to the nuts and bolts of how this actually works, if there's a fishery that wants to join in with the Marine Stewardship Council how does it go about actually getting certification?

Maylynn - We have various different departments with the MSC that focus on exactly that. So we have outreach staff that are based in different regions of the world that are the main contact points for fisheries that are interested in the program. So they are there to have conversations with interested fisheries, teach them about what are standard is, what's required to meet it.

There are certification bodies that are independent from the MSC that actually carry out the assessments and so a fishery client would contact a certification body, our outreach staff would say this is the first step you need to do, and then probably undertake a pre-assessment. So that certification body would look at the fishery, a first almost like a scoping exercise to tell them you're looking good we think you'd probably pass under full assessment, or you need to improve in these ways before you can have a chance at passing.

And once they've done a pre-assessment and perhaps improved the fishery to what ever level they need to be at, then they go into full assessment and start the actual MSC fishery assessment.

Helen - So you don't actually do those assessments yourself?

Maylynn - Yes, exactly. And that's quite an important thing about the MSC actually, is that it's a third party independent certification standard. So, the Marine Stewardship Council itself owns the standard, but the assessments are done by accredited certification bodies who then hire independent experts or fishery scientists to undertake the assessments.

Helen - What sort of tools, what sort of scientific tools are they using in terms of trying to understand how much of an impact a fishery is having?

Maylynn - If the assessment team is looking at how the stock is doing, one of the first things they'd look at is a stock assessment, if there is one. In Europe for example there's a body called ICES, the International Council for the Exploration of the Sea, that has scientists that do stock assessment on European fish stocks using various methods like they might do hydroacousitc surveys which is basically sticking a big microphone in the ocean and trying to sound-wave how many fish there are essentially, and estimate what the population is.

But in some fisheries there are no stock assessments and it's harder for them to meet our fishery standard because the way it was initially set up it's quite data heavy because we required a lot of things, evidence is provided for a lot of things like state of the stock, how much fish is caught, all sorts of things like that.

But in some fisheries there are no stock assessments and it's harder for them to meet our fishery standard because the way it was initially set up it's quite data heavy because we required a lot of things, evidence is provided for a lot of things like state of the stock, how much fish is caught, all sorts of things like that.

But for some small scale fisheries in developing countries it's pretty much impossible for them to show that using regular methods. Maybe it's just a small fishery with, I don't know, three vessels catching 40 a day and they've always caught 40 fish, and they aren't expending much more effort to catch that many fish, fish are the same size, that kind of thing.

So we've developed something called the risk-based framework that small-scale fisheries can use which is basically a way of looking at what impact they have on the fish stock without using such data-heavy protocols. So it's basically getting a group of stakeholders together to talk about what they've seen in the fishery in the past few years and try to assess a level of risk.

Helen - And, who pays for this certification? Presumably this isn't just a free systems you can't just join in and expect to have all these services for free, who actually pays for that?

Maylynn - I'm really glad you asked that question, actually because it's a message that I think is really important for the Marine Stewardship Council. So, the fishery being assessed pays for the assessment but they pay the certification body to undertake the assessments and the MSC does not receive any of that money. So, the fishery client is paying the certification body for their services basically.

Helen - Presumably you have ot keep quite close tabs on what's going on toa make sure they are maintaining that sustainability? How does that work?

Maylynn - Yeah, so if the fishery passes and gets certified, that certificate is valid for 5 years. And every year the fishery gets audited. The assessment team goes back to the fishery to check that they are still on track, that if there are any conditions on certifications, so areas where they are operating sustainably but could improve to even better practise.

And it's not possible for that fishery to be reassessed, which would happen at the end of the 5 year certificate, if they have not met their conditions or if something has changed in the fishery, it could cause them to fail and loose certification.

Helen - And, how do you feel the Marine Stewardship Council has changed the way that we fish the ocean?

Helen - And, how do you feel the Marine Stewardship Council has changed the way that we fish the ocean?

Maylynn - Yeah, this is something that we are looking into in more and more detail. And we do have some anecdotal stories to say that things are really improved. Like for example in the South African hake fishery since they've been certified their numbers of albatross bycatch have really, really decreased. So things like that have happened.

The MSC is really interested in seeing the broader picture, so what impact are we having on the oceans and marine sustainability generally. So, we're undertaking development of a monitoring and evaluation programme to really put in place a strategy so create impact factors - things that we monitor from year to year to track changes in the oceans and try and say what the MSC has contributed to make those changes.

Helen - Is it realistic to say that we can achieve this for the whole oceans and still have enough fish for everyone to eat? Or is this kind of a luxury for people who can afford to pay a bit more for their fish?

Maylynn - The MSC's vision is to create sustainable seafood for the next generation and to have oceans that are teaming with life.

So we're not looking to certify every fishery in the sea, but the goal is to reward those fisheries that are operating sustainably, with the eco-label and they can use that to market their product and perhaps get a price premium and hopefully that is an incentive for other fisheries to raise the bar and operate at that level as well.

I don't think that it's possible for all the fisheries to get certified but I think, and we certainly seen in the past few years an increasing number of fisheries coming forward. Whether or not that trend of increase is possible to continue the way is has, I don't know, but I think that the eco-label is still a valuable tool to influence the market that way.

Find out more

The Marine Stewardship Council

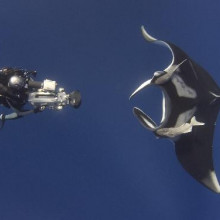

14:54 - Manta Ray Ecotourism

Manta Ray Ecotourism

with Andrea Marshall, Foundation for the Protection of Marine Megafauna

Andrea - Manta rays are caught across the globe. But when people imagine a manta ray fishery sometimes they don't quite understand the different types of fisheries that occur.

Obviously there are subsistence or artisanal fisheries that occur throughout their distribution where indigenous populations have been targeting them for food for many, many years. And that's not something that we're as worried about because those are sort of historical, traditional fisheries and a lot of times they catch animals in small numbers.

Obviously there are subsistence or artisanal fisheries that occur throughout their distribution where indigenous populations have been targeting them for food for many, many years. And that's not something that we're as worried about because those are sort of historical, traditional fisheries and a lot of times they catch animals in small numbers.

And then obviously you get bycatch fisheries that are also very, it's a very contentious issue because obviously the world needs to eat and there's fisheries for food that's caught around the globe. And unfortunately people are not catching sometimes in a sustainable way, and a lot of other animals die as bycatch. And for some reason manta rays seem to get caught up on nets when people are targeting things like tuna or whatnot.

People are not trying to catch the mantas and they're actually quite aware that you shouldn't be targeting mantas at all but there's not anything that they feel that they can do about it.

So, a lot of these traditional fisheries in places like Indonesia, or places like Taiwan, or even in India, they're catching large, large amounts of these mantas and mobulas in these nets which is disastrous to any of those populations.

Clearly the thing that we're most concerned with is target fisheries, places where people are actually targeting manta rays specifically because they are trying to extract the gill rakers from the animals to sell to the Chinese medicinal trade market.

And that is, I think, the most abominable use of mantas at the present time ,which is, you know, they're not using them for food or anything, they're actually targeting them for medicinal products that actually don't work. And I actually feel that's probably where we need to target most of our energy at the moment is trying to stop those fisheries.

Helen - And where in the world are mantas being targeted for their gills?

Andrea - Manta fisheries are springing up particulary in Southeast Asia. Some of the worst I've ever seen are in places like Indonesia where, you know, we've seen as many as 500 mantas a year were being taken from some of the fisheries in places like Lombok.

But we're also seeing that it's starting to spread to areas like India and Sri Lanka. Even across the places like Africa where local fisherman are now being told they can get large sums of money for taking these animals.

Helen - I guess a lot of conservationists feel that we should really be talking about providing alternatives for people who would like to make money from say fishing spcies like manta rays and ecotourism is something that's often put forwards as a possible alternative. Do you think we can make manta tourism work?

Andrea - This is probably one of the closest issues to my own heart because, you know, I do, you know, the majority of my research is done in Mozambique which is a coastline that is very, still undiscovered, still very pristine. So in the time, almost the decade I've been working in Mozambique I've actually started to see tourism on the rise in the area.

Andrea - This is probably one of the closest issues to my own heart because, you know, I do, you know, the majority of my research is done in Mozambique which is a coastline that is very, still undiscovered, still very pristine. So in the time, almost the decade I've been working in Mozambique I've actually started to see tourism on the rise in the area.

Fundamentally tourism can be a very positive influence especially when trying to make governments understand the value of animals and also see an alternative to fishing. So if you can show them that by sustainably using, you know, resources like their ocean resources to promote tourism in a sustainable way, then you can really, sort of, provoke change.

However, the actual tourism itself needs to also be done slowly and sustainably in a way that doesn't change the animal's behaviour.

And even in a place like Mozambique where tourism is just budding, we're actually starting to see a shift in animal behaviour already. And I know that many other people around the world specifically with manta rays have actually seen a negative response from too much tourism, you know, tourism that increases too quickly and lots of human traffic on the reef that's actually changing the behaviour of the mantas.

So I'm definitely encouraging people that want to promote tourism in their area for mantas as an alternative for fishing, to develop codes of conduct, to you know make sure that people are diving responsibly, and actually be very conscious of slow growth, you know, not expanding too quickly, not having too much human traffic, and actually using science, using biologists as a way to investigate how you can make it sustainable.

Like, one of the things that we've noticed in Mozambique is that people are actually diving with mantas at cleaning stations, and cleaning stations appear to be very critical habitat for mantas, but mantas only use them during the daytime hours. And in fact they seem to only use them from 7 o'clock in the morning to about 2 o'clock in the afternoon. Those are the exact same hours that divers are actually wanting to go on dives.

Like, one of the things that we've noticed in Mozambique is that people are actually diving with mantas at cleaning stations, and cleaning stations appear to be very critical habitat for mantas, but mantas only use them during the daytime hours. And in fact they seem to only use them from 7 o'clock in the morning to about 2 o'clock in the afternoon. Those are the exact same hours that divers are actually wanting to go on dives.

So actually if you have divers constantly on the reef during those hours mantas are getting no reprieve, no private time on the cleaning stations at all.

So it's been a suggestion of mine in Mozambique that if we're going to continue diving at these critical habitats with mantas that they do for a few hours in the morning and make sure for the rest of the day there's no diving allowed on the reef so that the mantas are getting a little bit of a reprieve from human traffic.

So I definitely think it's important to work with scientists to actually examine the behaviour of the animal so that you can modify, sort of, the diver behaviour to limit the impact.

So it's really, really important for everyone to work together and that's something that you don't often see around the world. Sometimes you get the tourism operations working against scientists because they feel that they have dissimilar objectives, but they actually have similar objectives, which is protecting animals and making sure it's a sustainable industry.

Find out More

Foundation for the Protection of Marine Megafauna

21:38 - Fish sanctuaries in the Philippines

Fish sanctuaries in the Philippines

with Jan-Willem Van Bochove, Coral Cay Conservation

Jan-Willem - Southern Leyte is found in the central Visayas of the Philippines. And it's an area that's renowned actually for the extremely high biodiversity both on the land but particularly in the sea.

The coral reefs there are known to harbour really vast amounts of different species. We had actually had a coral reef scientists visit our area, by the name of Doug Fenner. And on one of his dives that he did near our project site, he actually found more hard coral species than he had anywhere else in the world in a single dive. So that was an incredible result. And we realise this was a truly unique area.

The coral reefs there are known to harbour really vast amounts of different species. We had actually had a coral reef scientists visit our area, by the name of Doug Fenner. And on one of his dives that he did near our project site, he actually found more hard coral species than he had anywhere else in the world in a single dive. So that was an incredible result. And we realise this was a truly unique area.

Now Southern Leyte is not as populated as some of the other provinces. However the people that live there depend mainly on fisheries, or rice, or copra which is coconut farming, for their livelihoods. And as a result a lot of pressure is put onto the reefs there. Most of the fisheries are very small scale, little boats that go out, and they catch things like parrotfish and groupers and pretty much anything that they can get.

And this has been going on for several hundred years now. But even in Southern Leyte the population is increasing quite rapidly so there is a tremendous amount of pressure on the reefs and a lot of the reefs unfortunately have been overfished.

Sarah - And I suppose that's where the Coral Cay Conservation comes in. What is the project that you've been involved in, in order to help preserve this ecosystem?

Jan-Willem - Well we were initially invited there, Coral Cay were invited by the provincial governor at the time. It was quite a chance meeting with our senior CEO and founder Pete Raines who was sitting on an airline and happened to be sitting next to the daughter of the provincial governor. And that's how the ball got rolling.

We were invited there back in 2002. Since then our goals and aims have been expanded and shifted somewhat towards a lot more community-related work and that includes engaging communities, providing them with workshops where we educate them more about the management possibilities that they have in order to protect their reefs. But also to sustain their fisheries more effectively.

We were invited there back in 2002. Since then our goals and aims have been expanded and shifted somewhat towards a lot more community-related work and that includes engaging communities, providing them with workshops where we educate them more about the management possibilities that they have in order to protect their reefs. But also to sustain their fisheries more effectively.

One of those means is to set up what we call community-based marine protected areas. In the Philippines they're often called fish sanctuaries.

And what they are, so basically a small area of the reef that is set apart and within that area no fishing whatsoever is allowed. There is some limited diving allowed for tourists, but other than that the area is fully protected.

It's quite a small area. And in the Philippines the way it works is every province is divided up into municipalities. And within each municipality we have what we call baranguys, and each baranguy you can compare somewhat to a parish, so it's a very local level political unit of governance.

And so every baranguy typically has several thousand people that live within it and have a particular coastline. And that coastline is completely theirs, so they have ownership of their own reefs, which is quite a unique system in the world.

And the way we've managed to allow not only to enhance fisheries we've also worked closely with the tourism sector. So there are several, initially back in 2005 there were only two dive shops. Nowadays there is at least, I think there's 5 local dive resorts now.

And if divers wish to dive within one of those fish sanctuaries they pay a small fee, it's usually about a dollar or so, not very much money at all. But that money all goes back into the baranguy. So, the community sees financial benefits of establishing a fish sanctuary, which is great.

And if divers wish to dive within one of those fish sanctuaries they pay a small fee, it's usually about a dollar or so, not very much money at all. But that money all goes back into the baranguy. So, the community sees financial benefits of establishing a fish sanctuary, which is great.

But more importantly, what we're trying to establish is a situation where fish with a sanctuary are allowed to grow and actually reproduce and after several years fish start to leave the sanctuary and that's where they can get caught by the fishermen.

So it protects the fish within the sanctuary and in addition to that it also creates what's known as a spill-over effect. So, fish actually leave the sanctuary when there are at a size and an age where it's more productive for fishermen to catch them.

Sarah - And do you think, sort of, community-led projects like this where you really get the community involved, it's their area, and they get a financial benefit from it. Do you think this is something that would be beneficial to roll out in other areas not just in the Philippines but throughout other areas in the world as well?

Jan-Willem - Absolutely. I mean, I honestly believe that's the only way to really have successful management initiatives. I don't see it working any other way. At the end of the day, it's the people that live there that are the natural custodians of their reefs or forests or whatever it may be.

You've actually, you're going to run into the situation where those people are going to be, well they're going to be very upset by the fact that you've basically restricted them from doing what they've been doing for, you know, several decades if not hundreds of years.

So it's really, really crucial that you look for a means of allowing them to continue what they're doing at some level while also preserving those areas and it's for their own benefits.

So at the end of the day, if you can to convince that what you're doing is not only going to benefit the environment but is also going to directly help them, then I think you've a winning formula.

Sarah - And finally, what are your hopes for the future for this particular project?

Jan-Willem - Well, what we'd really like to see is a continuation of the establishment of these marine protected areas.

There's obviously a lot of other issues that I haven't really mentioned. There's a lot of, for example, upland deforestation, so we get a lot of sedimentation, a lot of mud that gets washed onto the reefs and smothers the reefs. And that's been a big problem, in addition to pollution and other local issues like that.

So, what we're doing is trying to expand the project to also include a forest component. So, again working with local communities but this time round, up in the rainforests and working with them to help protect the rainforest there in a similar means to what we've been trying to do with the coral reefs and we've managed to do quite successfully.

That of course will require a lot more resources, and that's something that we're working on. And I think as far as Coral Cay's concerned, it's really key that we start taking on a more holistic, what we call a reef to ridge approach, a ridge to reef approach. So that's you're not only protecting the reefs but you're also protecting the upland forest, because they certainly go hand in hand, and you need to address both of those if you want to really have an effective conservation management scheme.

Find out more

Coral Cay Conservation

30:04 - Critter of the Month - Brown Pelican

Critter of the Month - Brown Pelican

with John Bruno, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill

This month's critter is something that lives above, on, and even in the sea... The Brown Pelican.

John - My name's John Bruno, I'm a marine ecologist at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. And if I were to be a marine animal I would be a brown pelican.

Brown pelicans live in Nnorth and South America along the coast. They're sea birds, they eat fish almost exclusively. And of the 8 species of pelican they're the only ones that dive into the water to catch their fish.

Brown pelicans live in Nnorth and South America along the coast. They're sea birds, they eat fish almost exclusively. And of the 8 species of pelican they're the only ones that dive into the water to catch their fish.

They live part of their lives just sitting in trees, hanging out, part of their lives floating on the ocean. They migrate quite far seasonally, so you'll often see them skimming in these long lines just over the waves. And of course they get to go into the ocean as well. So they'll dive in pretty deep, a couple of metres sometimes maybe a little more than that, catch a fish, bring it up to the surface, and gulp it down.

For a long time in North America they were threatened by DDT which made their egg shells too thin for the chicks to survive but that problem largely been solved. So their populations are recovering, doing really well.

Of course the Gulf Coast oil spill is causing them lots of problems, at least locally, and one of the most horrific images from that tragedy is seeing pictures of oiled pelicans on the beach.

Find out more

Guide to brown pelicans Pelecanus occidentalis at the

Cornell Lab of Ornithology

Comments

Add a comment