Art meets science this month on Naked Oceans as we meet artists who bust myths about the dark, scary, monster-filled depths. We find out from sculptor Jason deCaires Taylor about how his work transforms into artificial reefs. We chat with National Geographic photographer Brian Skerry who blends the beauty of the oceans with the problems they face today. And we hear about a man who brought the beauty of the underwater realm to the masses before the invention of underwater cameras. Plus, our critter of the month is a curious beastie that can't see light, but can see heat.

In this episode

01:32 - Biodiversity can buffer against nutrient pollution

Biodiversity can buffer against nutrient pollution

A paper published in Nature by Bradley Cardinale from the University of Michigan suggests that biodiversity in aquatic ecosystems can help to buffer a system against increased nutrient input.

One of the major impacts of human activities on aquatic ecosystems is increased input of nutrients like nitrogen, from runoff from agriculture, or by sewage contamination. This can create problems like eutrophication and dead zones, where there is too little oxygen in a body of water for species to survive.

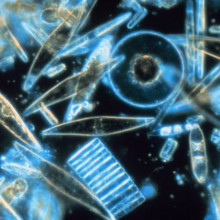

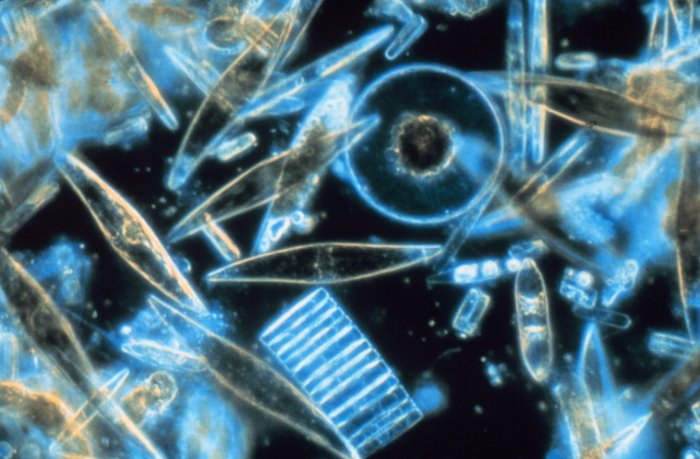

What Bradley did was to take 8 different species of algae and diatoms, and introduce them to experimental 'streams' where the heterogeneity of the environment - so things like the water speed and levels of disturbance - could be manipulated. When the species were able to all occupy different niches - so each perform different functions within the ecosystem, the uptake of radioactively labelled nitrate was higher than when biodiversity was experimentally reduced.

The unfortunate fact, which Bradley does point out in the paper, is that increased nutrient input to an aquatic system does actually reduce biodiversity, which given these results is more worrying. So as biodiversity is lost, the ability of an ecosystem to deal with and sequester extra nutrients like nitrogen will decrease.

Although this was a freshwater study, nutrient runoff in coastal areas is a major problem for marine species too, so a possible future direction of research could be whether the same effect would be seen in a marine ecosystem.

03:22 - Mangroves mega carbon stores

Mangroves mega carbon stores

Mangrove forests store more carbon than we previously thought, bolstering global incentives to protect and replant them. Much of the mangrove carbon is locked up in rich organic soils beneath them.

Publishing in the journal Nature Geoscience, a team of researchers based in Indonesia and the US measured the amount of carbon stored by mangroves in 25 sites across a large tract of the Indo-Pacific spanning Indonesia, Micronesia, and Bangladesh: a much larger area than previous studies have looked at.

Publishing in the journal Nature Geoscience, a team of researchers based in Indonesia and the US measured the amount of carbon stored by mangroves in 25 sites across a large tract of the Indo-Pacific spanning Indonesia, Micronesia, and Bangladesh: a much larger area than previous studies have looked at.

They estimate that up to 10% of the carbon dioxide emitted globally when forests are cut come from areas of cleared mangroves, even though this accounts for under 1% of the area of tropical forests.

Mangroves are disappearing fast. We've already removed more than half the world's mangroves in the last 50 years. They've been cut down to make into firewood and charcoal, and to make way for fish and shrimp farms.

There are many reasons why mangroves need protecting. They provide vital nursery areas for commercial fish, they protect coastlines and so play an important role in protecting coastal communities from the impacts of sea level rise.

This new study lends yet more weight to the argument for protecting mangroves, with their substantial carbon stores adding to the major benefits they provide.

Find out more

Daniel Donato et al. Mangroves among the most carbon-rich forests in the tropics.

Nature Geoscience.

Blue carbon portal

06:20 - Shifting perspectives with underwater photography

Shifting perspectives with underwater photography

with Brian Skerry

Photojournalist Brian Skerry has been a contract photographer for National Geographic since 1998 and specialises in capturing images of the underwater world that portray not only the beauty of the oceans but also the problems they are facing.

Brian - I've been diving for a little over 30 years and making pictures in the ocean for most of that time and throughout most of my career I have seen essentially what I would call celebratory pictures of the ocean. You know, some wonderful pictures that show the majesty and beauty in the ocean, but very little had been done along the lines of the problems in the ocean.

Brian - I've been diving for a little over 30 years and making pictures in the ocean for most of that time and throughout most of my career I have seen essentially what I would call celebratory pictures of the ocean. You know, some wonderful pictures that show the majesty and beauty in the ocean, but very little had been done along the lines of the problems in the ocean.

So, my work has had this somewhat of an evolution, I guess, in my career, in the sense that I too want to make beautiful, celebratory pictures, and in the early days that mostly what I did. But these days I try to balance the happy pictures with some the other side of the story kind of pictures, the pictures that show some of the problems.

I'd like to think that my images and my stories are helping people to get a better grasp of these sometimes complex issues that occur in the ocean.

Helen - And you mention the complexity when it comes to problems in the oceans. There must be some things that are really difficult to find images to portray what's going on?

Brian - One of the first rather large stories that I proposed to National Geographic about issues in the oceans, it was a story that was published in 2007 about the global fish crisis - the problems of overfishing worldwide - and I had been researching and talking to the editors about this for the better part of two years.

It was a difficult thing to get your head around. It was something that we knew was happening, we'd read a lot of scientific papers, there was a great paper that was published in the British journal Nature, that has stated 90% of the big fish in the ocean had disappeared in the last 50 or 60 years. But to many, it was a difficult thing to photograph. How do we translate photojournalistically these things that have disappeared.

So, ultimately over a bit of time I came up with a 4 tier plan. The first part of the story  for me was about making pictures that would get people to appreciate the animal. They may never warm up to a fish the way they do a polar bear, or some fuzzy, cute mammal on land, but at least they could appreciate it. And I wanted them to see these animals in a wildlife way.

for me was about making pictures that would get people to appreciate the animal. They may never warm up to a fish the way they do a polar bear, or some fuzzy, cute mammal on land, but at least they could appreciate it. And I wanted them to see these animals in a wildlife way.

The second step was to then show some of the horrific problems that are occurring, the ways that fish are harvested and caught in the ocean, things like sharks in gill nets and bycatch from shrimp trawlers and longlines with illegal fish being caught, and these kinds of things.

Another step was to show how it's affecting humans, places in West Africa that have lost their only source of protein because first world nations have come in with factory trawlers and taken away all of their fish.

And the last step of the story to me was about hope. If it's all over then what's the point? Showing at least some of the solutions, places where they're creating marine protected areas. With less than a fraction of 1% of the world's oceans that have truly been protected from commercial fisheries we need to do a better job of creating places where marine life can thrive.

I think my work helps to allow readers to digest this quickly and easily. They can see the photographs, they might be sitting at a dentist's office of the doctor's and they pick up the magazine, see a photo that engages them and they want to read the caption and then hopefully read the story and learn a little bit more. So, I'd like to think that those kind of issues can be treated photographically in a way that makes people learn more and want to know even more.

Helen - Is there any way that you've been able to gauge or get a feeling for how your images and your work is maybe even helping to change people's behaviour in terms of the decisions their making about what they eat. Do you have any way of tapping into that?

Helen - Is there any way that you've been able to gauge or get a feeling for how your images and your work is maybe even helping to change people's behaviour in terms of the decisions their making about what they eat. Do you have any way of tapping into that?

Brian - Yes, I mean it's not anything that I can quantitatively say Yes, I can give you these facts and figures. But I get a sense from a couple of different things and they're by no means scientific. There's been some evidence that things have progressed.

For example, after a story that I did on right whales a couple of years ago, I did a story on the most endangered species of large whale in the world, the North Atlantic right whale and the southern right whale.

There had been legislation languishing in Congress here in the US to slow the speed of shipping traffic coming into critical habitat for right whales where moms and calf's often live during parts of the year. And that legislation had never been passed but after my story came out, according to the scientist who'd been working on this for many years, the Congress did act and were able to pass this legislation. So, I don't know if we can draw a direct result, but they seemed to think it certainly helped.

There was another example, in the final days of the Bush Administration here in the US where they enacted some marine protection for a number of places in the Pacific, a place called Kingman Reef, and some other places. And I had just published a story in National Geographic about Kingman Reef about it's magnificence and how relatively pristine it was compared to many other coral reefs because of its remote location.

There was another example, in the final days of the Bush Administration here in the US where they enacted some marine protection for a number of places in the Pacific, a place called Kingman Reef, and some other places. And I had just published a story in National Geographic about Kingman Reef about it's magnificence and how relatively pristine it was compared to many other coral reefs because of its remote location.

It's certainly isn't just because of those stories, and I could never claim that, nor would I want to. But I do think the combination of great science along with those kind of images can have an impact.

The other thing is just talking to people and getting messages. I literally get dozens of messages every month and literally say, "I had no idea that for every pound of shrimp that I eat, there's 6 or 10 pounds of other animals that die in the process from bycatch. I didn't know about that".

And now they have changed their behaviour. And there' s no way for me to measure that but I'd certainly like to think that that's the approach, if we can work from the grass root level up by educating and bringing awareness to people, and from the political, legislative level down, that we have a chance.

Helen - It seems to me that spending my time taking pictures of beautiful underwater life, just sounds perfect. What is the reality of being an underwater photographer?

Brian - Well, that is a big part of the reality is that it is wonderful but, like any job I  suppose there are up sides and downsides. And certainly the good outweigh the bad. Some days the weather is just terrible and you sit for weeks waiting for the weather to stop being windy or the visibility to clear up. Sometimes the animals don't show up. You go to do a story about tiger sharks, and there's no tiger sharks there. Equipment sometimes breaks, you know, we're dealing with taking electronics into salt water.

suppose there are up sides and downsides. And certainly the good outweigh the bad. Some days the weather is just terrible and you sit for weeks waiting for the weather to stop being windy or the visibility to clear up. Sometimes the animals don't show up. You go to do a story about tiger sharks, and there's no tiger sharks there. Equipment sometimes breaks, you know, we're dealing with taking electronics into salt water.

There's all these things that can go wrong and as I often tell people, your success I suppose in anything in life but certainly in this business will be determined by how well you overcome problems.

And I don't want to appear like this is a terrible job, because it's fantastic. I love what I do, I meet great researchers, and boat drivers, and dive guides, and all these great people that I've learned so much from.

And I get to make photographs. I get to preserve an instant in the ocean. It's a moment in time. You're trying to capture this blend of gesture and grace with an animal, and light and motion all in still frame and sometimes it works, it all comes together and you get this truly magical moment that's preserved forever.

Find out more

Brian Skerry's website

Watch Brian's

TED talk

International League of Conservation Photographers

Find out more about Brian's work in his new book Ocean Soul, due out November 2011

15:42 - Revealing ocean wonders before underwater photography

Revealing ocean wonders before underwater photography

with Philip Ball

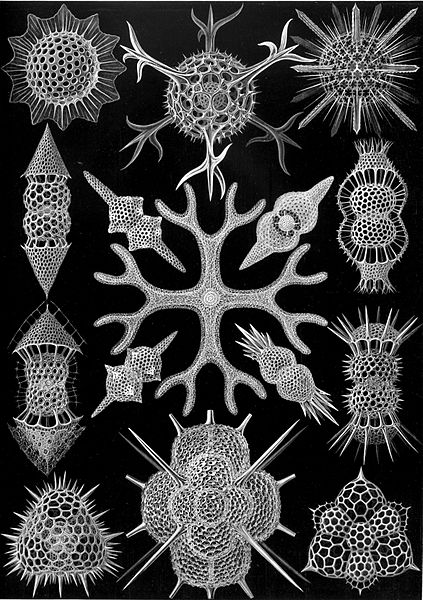

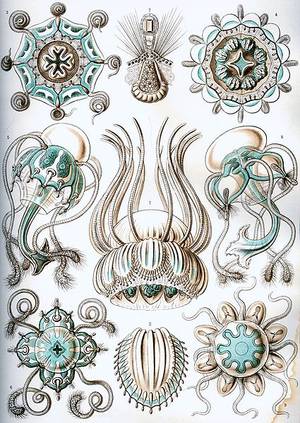

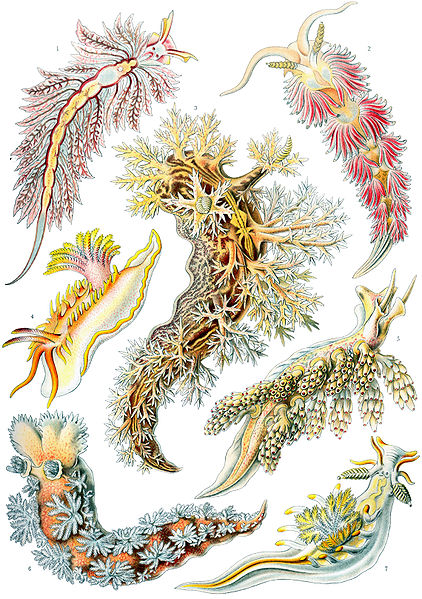

Ernst Haeckel's drawings of the intricate sealife were a sensation among scientists and artists alike.

Helen - First of all Philip, just who was Ernst Haeckel and what sort of things did he get up to?

Philip - Well he was a zoologist, or biologist, or call it what you will, someone who was interested in natural history, at the end of the nineteenth century. He was a professor of zoology at the University of Jena in Germany. And there he was one of the key promoters of Darwinism in Germany. He took Darwin's ideas and popularised them there, but he popularised them very much in his own way, it was a way that actually slightly baffled Charles Darwin.

Philip - Well he was a zoologist, or biologist, or call it what you will, someone who was interested in natural history, at the end of the nineteenth century. He was a professor of zoology at the University of Jena in Germany. And there he was one of the key promoters of Darwinism in Germany. He took Darwin's ideas and popularised them there, but he popularised them very much in his own way, it was a way that actually slightly baffled Charles Darwin.

He had an idea, I suppose, that all life is guided by organisational forces and principles. So it was quite an unorthodox kind of Darwinism.

Helen - And that sort of idea of shapes and patterns and organisation, that spilled over into this book that he produced Kunstformen de Natur, or Art Forms of Nature, which was this series of intricate drawings of living organisms, many of them from the sea.

Philip - Yes, well this was a series that Haeckel produced between 1899 and 1904 and he was an extraordinarily good draftsman. He did all the drawings himself. Some of them were of large creatures like fishes and birds and so forth, but a lot of them were microscopic creatures that he had found looking through the microscope he'd found in seawater.

They were organisms with exotic and unfamiliar names, things called radiolarians and diatoms, coccolithophores and dinoflagellates. And all of these are essentially single-celled organisms. Some are plants, some are kinds of plankton. Others are very primitive forms of animals called protozoa. And all of them build protective shells that have the most extraordinary shapes, and this was what excited Haeckel because this seemed to lend some support for his idea that the world, that life really is permeated by these organisational forces that operate all the way from very primitive, single-celled creatures, all the way through to higher organisms.

diatoms, coccolithophores and dinoflagellates. And all of these are essentially single-celled organisms. Some are plants, some are kinds of plankton. Others are very primitive forms of animals called protozoa. And all of them build protective shells that have the most extraordinary shapes, and this was what excited Haeckel because this seemed to lend some support for his idea that the world, that life really is permeated by these organisational forces that operate all the way from very primitive, single-celled creatures, all the way through to higher organisms.

So he looked at countless examples of these shapes in the microscope and drew them in the most elaborate way in this book Art Forms in Nature.

And the drawings that he made turned out to be very influential among some artists and designers at the time. They just found a huge amount of inspiration in these pictures.

Helen - Am I right it's the Art Nouveau movement that embraced a lot of these shapes and patterns that Haeckel came up with?

Philip - Yes, they're very characteristic of what we now associate with Art Nouveau. And some of the artists from that movement were inspired to make designs of things like furniture, that were based on some of the shapes of the radiolarians that Haeckel had drawn.

Helen - Was he a huge hit at the time? Did lots of people go out and buy this book?

Philip - Yes they did. Well certainly artists did. And you can see why when you look at the book. It is stunning. It's stunning but also very weird. These shapes that were found in the exoskeletons of these tiny creatures were like nothing we'd seen before in the living world.

Philip - Yes they did. Well certainly artists did. And you can see why when you look at the book. It is stunning. It's stunning but also very weird. These shapes that were found in the exoskeletons of these tiny creatures were like nothing we'd seen before in the living world.

In fact when some of these creatures were first observed in the early 19th century when the ones called coccolithophores were first observed, people weren't sure whether what they were seeing were the products of living creatures or some kind of strange crystal. Because they had this very strange, orderly pattern to them, but also extremely elaborate.

They seem to stand at this juncture between the living and the non-living worlds. They are purely, completely the product of living creatures but it also turns out they are shaped by the same sorts of forces that can organise non-living systems things like bubble rafts and foams.

So they are very, very unusual. It just seems that artists at the time were completely captivated that things like this could exist in the world at such a tiny scale.

Helen - And would you say that Haeckel's work continues to have a legacy today? Do people still look to his work for inspiration or for ideas?

Philip - Well, yes they do. I think certainly for inspiration because whatever you make of Haeckel, he was quite a controversial character, the images that he's left us with are still as beautiful as ever, as striking as ever.

One has to say that occasionally you suspect that actually Haeckel was slightly  embellishing them. Certainly the way he arranged his pages was very decorative. So this wasn't a straight scientific record. He was clearly trying to do something artistic with this too, and sometimes he probably embellished the shapes that he saw to make them more regular and orderly.

embellishing them. Certainly the way he arranged his pages was very decorative. So this wasn't a straight scientific record. He was clearly trying to do something artistic with this too, and sometimes he probably embellished the shapes that he saw to make them more regular and orderly.

Nevertheless, what his artwork did show us was that there does seem to exist at all levels in nature some kind of pattern and form and symmetry, and it's really that that is inspiring in Haeckel and was really that that inspired the first thorough study of pattern and form in nature which was made in 1917 by a Scottish zoologist called Darcy Wentworth Thompson. Darcy Thompson included a lot of Haeckel's illustrations in his great book which was called On Growth and Form.

Find out more

Philip Ball

22:15 - From art to artificial reefs

From art to artificial reefs

with Jason deCaires Taylor

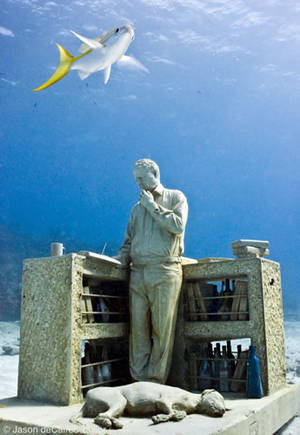

To visit Jason de Caires Taylor's artwork you have a pay a visit a very unconventional gallery. Installed on the seabed in various locations around the world, his sculptures take on a life of their own as they become engulfed in marine organisms and form artificial reefs that spread a message about people and the oceans.

Jason - Well first of all I create artificial reefs but using sculptures. And the main aim of them really is not only an art project but also a conservation project. All of the sculptures go on to create reefs which not only aggregate fish and promote corals but they also diverts tourists away from natural reefs which leaves them time to regenerate on their own accord.

Jason - Well first of all I create artificial reefs but using sculptures. And the main aim of them really is not only an art project but also a conservation project. All of the sculptures go on to create reefs which not only aggregate fish and promote corals but they also diverts tourists away from natural reefs which leaves them time to regenerate on their own accord.

I hope to use the sculptures as a way to symbolise us living in a symbiotic relationship with nature not just us always working against it.

Just the image of a human figure ingrained with marine life is affording it a certain type of respect. I really am worried about the state of our oceans and how they're changing so dramatically and I'm trying to use the work to highlight some of these issues.

Helen - So, people visiting your work obviously have a very different perspective to visitors at a regular art gallery. The light changes, people can hover over your work, or swim alongside it. Do you see that as a challenge or as an opportunity?

Jason - Both really. It's definitely a new way to look at art. There's so many different perspectives and it's such a new world down there. Each visit is never quite the same. So I have people that go one day and it's overcast and stormy and the works take on a certain meaning. And then they go another day and it's light and euphoric and it's a completely different experience.

So I actually think it adds to the work.

Helen - How do you choose who you're going to make these sculptures out of? And do you get a lot of volunteers? It sounds like it's quite a messy business.

you get a lot of volunteers? It sounds like it's quite a messy business.

Jason - Mainly with the Silent Evolution I was looking for a cross section of society, so I was aiming to get people from different communities, different ages, male and female, different age groups. So I was constantly on the look out for people just in every day life. And if I saw someone that had particular characteristics or fitted any of the profiles then I'd approach them and ask them to see if they wanted to participate.

I'd bring them down to my studio then it's a case of them getting undressed to their underwear, getting covered in Vaseline then applied with all these very messy materials, alginate and plaster. And it's quite a long process. From there we make a plaster original, then we make a silicon mould, then finally it's a cement piece.

Helen - And how do people respond when they see themselves cast in cement? And do any of them go and visit their own sculpture installed on the seabed?

Jason - Yes, a few people have gone to visit it. It's actually interesting because obviously people change. Some of the children I've done are now much taller than they were a year ago. One woman was pregnant, she's had her kid. Actually one of the models died a few months ago, so it really did cover the whole circle of life.

Helen - And you talk about the people change, but your sculptures change too don't they? In a way you're sort of giving them over to the sea and to sealife. How does that feel? Does it feel like they're not yours anymore?

Helen - And you talk about the people change, but your sculptures change too don't they? In a way you're sort of giving them over to the sea and to sealife. How does that feel? Does it feel like they're not yours anymore?

Jason - I personally find it the most exciting and dynamic part of the work. It's so unpredictable. I went recently and the hair of one of the sculptures has started growing this sort of curly algae and I couldn't ever had predicted that would colonise that particular part. But it just looks so perfect in its spot.

I almost feel some days that I'm cheating in some ways as a sculptor because I never actually finish the work, it's like another shift of artists comes along and adds the finishing touches.

Helen - And do you ever feel tempted to say, oh no I don't want that bit there, and do you ever feel like you want to interfere with what nature is doing to your work?

Jason - Sometimes, sometimes. I've done a new piece which has a false lung inside it and I'm trying to keep that lung clear so that air can be exhaled out of the sculpture. So I'm actually trying to stop the growth on that part and it's actally very difficult to do.

I did a piece past year that's called Man on Fire and on that one I planted a particular  species of fire coral and the aim was that he was going to turn completely yellow over time and look like he's on fire. But what happened is another algae has attached onto it and it's having a little war with the fire coral. So I think I'm going to have to send some more fire coral troops in to win that war for it to complete its objective.

species of fire coral and the aim was that he was going to turn completely yellow over time and look like he's on fire. But what happened is another algae has attached onto it and it's having a little war with the fire coral. So I think I'm going to have to send some more fire coral troops in to win that war for it to complete its objective.

Helen - What sort of other creatures are colonising your work? What else are you seeing turning up?

Jason - There's masses of little relationships going on. We have lots of lobsters that colonise underneath all the gaps in the sculptures. We have these very territorial fish called damselfish and they claim a little patch of the sculpture and they rigorously defend it, so whenever I go to take photographs these fish come and bite me on the hands because I'm invading their area, which is interesting.

There recent installation which I've just finished in Cancun is this mass gathering of 400 people, and it's actually designed so that it creates all this void area beneath the peoples' feet and that's what fish love to take refuge. It's been there 6 months now and I went back last week and there's literally thousands of fish that have colonised there already and it's really exciting to see.

You can actually see the dynamics because predator species like the barracuda hover around the top of it and the big schools of fish duck and weave in between the legs to avoid being eaten. It's really fascinating.

You can actually see the dynamics because predator species like the barracuda hover around the top of it and the big schools of fish duck and weave in between the legs to avoid being eaten. It's really fascinating.

Helen - On a practical note, how to you make sure your work doesn't get broken up and swept away by currents? You've got the ocean to deal with, how do you make your sculptures last in that sense?

Jason - That's probably the number one biggest challenge is protecting the works especially where I'm working at the moment in Cancun because it's so prone to hurricanes. A lot of research and a lot of design has gone into dealing with that.

At the moment all the sculptures are incredibly heavy. The recent ones of the Silent Evolution were put down in units and they were 5 tonnes each unit. And then those are drilled into the sea floor.

Working underwater I can't use any metals and 90% of public sculpture uses metal. So it's been quite difficult finding alternatives.

Helen - Presumably you can't use metals because that would just rust away?

Jason - Yes, they start rusting and degrading. The sculptures have to be there for a very long time to establish slow-growing hard coral. So it's vital that they remain intact.

Helen - What's next for your underwater work?

Jason - I'm continuing in Mexico. I'm exploring a whole new series of pieces which are going to be kinetic. So they're going to be moving underwater with the currents. But it's actually going to be using gorgonian fan coral. There's a lot of it around here and it's quite often damaged by storms or strong weather. So we find a lot of it dislodged and we're using those dislodged pieces to attach to the sculpture so it'll have wings that move underwater. So it'll be very interesting to see how it works out.

Find out more

Find out more

Underwater Sculpture by Jason deCaires Taylor

Comments

Add a comment