In this Special edition of the Naked Scientists, we explore the science of the Glastonbury Festival. We find out what it takes to turn a farm into a city and back every year, and how to keep clean water flowing in, and waste flowing out, for nearly 200,000 revellers. We examine the scientific issues being discussed at the festival by groups like Greenpeace and Water Aid, and ask Baba Brinkman, Paloma Faith, Josie Long and Robin Ince if scientific discussion can find a home at a festival of performing arts.

In this episode

00:48 - Building the basics of Glastonbury

Building the basics of Glastonbury

with Phil Miller, Infrastructure Manager, and Georgie Pope, Glastonbury Festival

Ben - The Glastonbury Festival of Performing Arts is the largest green field music festival in the world. This year, it celebrated its 40th anniversary and nearly 200,000 people shared it with them. But turning a farm into a city is no easy feat, especially when it needs to be a working farm again within just a few weeks. For the festival to run smoothly, there must be adequate water, sanitation, road access, and electricity to all corners of the site. The infrastructure that keeps the water flowing in, and the waste flowing out, is managed by Phil Miller. He explained the challenges of putting on the festival.

Phil - Our biggest challenge is to make sure that you have all the facilities in place for that volume of people - not only the people that are ticket holders, but the vast amount of staff that are on-site as well. So you must make sure there's sufficient water, adequate roads to get here, sufficient parking, sufficient toilets, sufficient showers; all the facilities. It's a global problem for the site if you haven't got them in place.

Ben - And of course, the rest of the year, this is a working farm. You need to be able to reduce the impact that the festival has to keep the farm running.

Phil - We try not to impact on the farm at all if we can help it. We leave the setting up of the site until May generally. There is some impact during May, but not completely. The cattle have still been able to use their fields during the May period. There's a time set for the license purposes that they have to be off, I think it's about 28 days before the event. And then after the event, the clearing up process should take approximately 3 to 4 weeks - so the site's reinstated to a normal farm again.

Ben - So starting with the transport issues, how many roads do you need to build and can they just stay there all year, or do you need to build temporary structures as well?

Phil - The site has probably over 20 miles of road, including the camping areas and the temporary roads which are laid. They are generally used as farm tracks during the winter months for farm operations, because obviously it includes several farms - the amount of land that we need to actually put the whole event on. As well as the roads, it's bridges, and bridges are sometimes not always strategically located. We have to strengthen them - with articulated lorries coming on to the site now, in an excess of 40 tons, we have to make sure that the loading capacity is appropriate for whatever vehicles come on to the site.

Ben - And in fact you've built nine new bridges in the last year.

Phil - We have completed nine bridges. I mean, of those nine, three to four are pedestrian bridges with load bearing obviously a lot less and a lot easier to provide. But the other ones are mainly load bearing capacity. Some aren't necessarily new bridges - they are old bridges that were reinstated where they'd failed the test of time.

Ben - Phil Miller. So I could see firsthand what goes into preparing the site, I was taken on a guided tour by Georgie Pope. First of all, a half-built bridge...

Georgie - Now, we're at Bella's Bridge which is the bridge that Michael Eavis has said is going to be the loveliest bridge in the whole country. It's named after Bella Churchill. It's in the corner of the area that she liked the best.

Georgie - Now, we're at Bella's Bridge which is the bridge that Michael Eavis has said is going to be the loveliest bridge in the whole country. It's named after Bella Churchill. It's in the corner of the area that she liked the best.

Ben - It obviously isn't quite finished at the moment. Infact we are standing next to it on some scaffolding. I assume it's all going to be ready in time for the festival?

Georgie - I assume so too, I hope so.

Ben - It just looks like a fairly normal bridge to me. What is it that's going to make this the most beautiful bridge in the country?

Georgie - It's got this lovely, grey stone work over here which I think is quite pretty and then it's got this wonderful curve which gives it that humpback look. It's a very attractive bridge.

Ben - So once you have all these people here, obviously, one of the most important things is to keep them well-watered. Supplying water for this many people, keeping it clean, and being able to get it around the whole area must be very difficult?

Phil - Yes. It's been a learning curve over the last few years and the new water regulations have forced the festival to actually introduce improved facilities for all the people that attend the event. What we've done in actual fact, is build two category V reservoirs (that's the highest category they can possibly have for reservoirs). Those tanks will hold about 2 million litres of water. The holding capacity is not the most important thing; the most important thing is that if you're using water at 25 litres a second, we need to replace the reservoir water with 25 litres a second. So what we've done this year is put in an underground water main, a 6-inch main that runs around the site and will be operating as any other town or city in the country. From that, there will be spurs, taking the water to the strategic locations, giving us what I hope will be the appropriate water pressures.

Ben - How do you keep that water clean?

Phil - Because it is directly sourced from Bristol water supplies and we have got the category V tanks, there shouldn't be any contamination issues. New water regulations have stated that there will be tests and we have 10 samples a day taken on-site, and that's for chlorine levels, for chemical, or microbiological samples. We shouldn't have any contamination from those sampling points. If we did, then obviously we would have a problem, but I'm fairly confident that with all the facilities we put into place, because we've renewed all the taps on-site, as well as renewed pipes and having the reservoirs, we shouldn't have any contamination issues.

Ben - Thinking about the reservoirs themselves, how are they built? What did you have to do to put reservoirs into what's normally a farm?

Phil - Well first of all, you have to get some of the permissions in place. We also have to have the licensing section of the council approve whatever changes we make on-site. So there are a lot of people that become involved in permissions and once those permissions are in place, the work is obviously checked after the event.

At the moment, we're looking at finding an accredited company to test out water pressures for us to make sure that all the systems being installed are going to be safe and usable prior to this year's event.

Ben - And you were able re-use the stone that came out when you actually excavated the reservoirs.

Phil - Yes. Most of the stone that came out that we dug out for the reservoir has gone back into roads and as I mentioned earlier about the bridges, the strength of the roads and the bridges are really important not only for the weight of the vehicles, but the volume of vehicles that we have on-site. We're very conscious of our carbon footprint in trying to make sure that we do everything that we should do and we take into account the local community as well. Reducing the lorry movements on-site is one way in which we do that, and we are putting some of the materials in the reservoir back in roads. We're bringing in lock gates from the British Water Board that we're using to make bridges with and seating around the site. All the time, we are thinking about how we can best recycle the equipment we have for the facilities that we need.

Phil - Yes. Most of the stone that came out that we dug out for the reservoir has gone back into roads and as I mentioned earlier about the bridges, the strength of the roads and the bridges are really important not only for the weight of the vehicles, but the volume of vehicles that we have on-site. We're very conscious of our carbon footprint in trying to make sure that we do everything that we should do and we take into account the local community as well. Reducing the lorry movements on-site is one way in which we do that, and we are putting some of the materials in the reservoir back in roads. We're bringing in lock gates from the British Water Board that we're using to make bridges with and seating around the site. All the time, we are thinking about how we can best recycle the equipment we have for the facilities that we need.

Ben - So we've come to see not only the completed reservoir, but also the reservoir that's still under construction. What have we actually got in front of us? It looks like a bomb shelter.

Georgie - It would probably look after you if a bomb hit it. It's going to contain a million litres of water, which is about as much as an Olympic swimming pool. It's deeper but narrower.

Ben - But about the same length, about 50 metres long. There seems to be an enormous amount of concrete.

Georgie - Yes, but there's also - you can see that we've dug out the rock there which will be used for the roads. So there's something re-usable about this.

Ben - But once it's all completed - and it looks like it's getting fairly close now - what will this actually look like? Is this going to be this concrete monstrosity all year round?

Georgie - Well, if you look over there, that's the site where the other million-litre reservoir, and it's completely grassed over, so there's no sign of it at all. The only clue that it's there at all is that concrete periscope type of thing which is where you can go down, and it's a viewing chamber and you can see the levels, and check everything is as it should be.

Ben - So, all that's left other than beautiful looking green grass is a small area where you can go and inspect the water from.

Georgie - Yes. Don't worry. It won't look like this.

Ben - Inevitably, this many people over this much time are going to create an enormous amount of human waste, an enormous amount of sewage. What can you do with that?

Phil - Well, there's not a lot you can do with that and obviously, it would have to be taken to respective plants and discharged in the normal way. We have improved the way in which that movement would happen over the last year. The haulage was quite a long way at one stage, and now, we've improved the local facilities at our expense to make sure that we can haul much shorter distances, so that we aren't having an adverse effect onto the planet in that respect. It is a high volume of material that just has to be disposed off - we have looked at biodigesters. Biodigesters are great for our animal waste at the moment. If we could use it for human waste, we would. But we're not at that stage yet and I don't think the information is available for us to consider that.

Ben - But the knock-on effect of the waste created at the festival is that now, the local area has better facilities to clean sewage all year round.

Phil - Well, the money that's been given to Wessex Water to improve their plant obviously would have an impact all year round. We only use that facility for 17 to 20 days. So it's a very short life span for us, but the facilities have been improved.

Georgie - We are standing next to three huge cylinders that are going to contain all the human waste produced by the festival, by which I mean, poo.

Ben - These are enormous silos. How much waste can you actually fit in one of those?

Georgie - Well, I think this new big one that's being built takes almost 2 million gallons of waste.

Ben - Two million gallons of human waste.

Georgie - Yes.

Ben - How much actually gets produced throughout the festival?

Georgie - Well, it never actually gets to the top because it will get half-filled and then trucks will come halfway through here every day, and take some off it. So, it's difficult to say exactly how much because it will never reach the top, but somewhere in the region of twice that.

Ben - So almost 4 million gallons of human waste.

Georgie - Yep don't say it too many times. It's horrible, but it's the reality of it and it's something amazing we have to deal with. It's something that in a city, the sewage department is dealing with every day, but revellers and party goers complaining about lack of loos aren't necessarily thinking about what's happening to their waste.

Ben - And of course, we're so used to the fact that our waste goes down into the sewage and is dealt with straight away, that this really, really brings it to mind that it has to go somewhere and something has to happen to it.

Georgie - Yes and quickly.

Ben - How long does it take all in all? What's the timeframe to turn a farm into a festival and back into a farm?

Phil - Well we try to do it in a shortest period of time possible, but I would say that we would probably need 6 weeks to build it and 4 weeks to dismantle it. But there are some things onsite that take much longer - and that would be things like the reservoir and bridges. They need a little more engineering time.

Ben - And how many people are involved?

Phil - Well, the licence has a figure quoted for about 35,000 staff - a lot of those staff would be security staff. Within the infrastructure section, we have about 1,000 people that work for us. There's also a lot of volunteers and if it wasn't for the volunteers, it would be very difficult to achieve the levels of service that we do.

Ben - The volunteers also, I understand, help a great deal with dealing with all the rubbish that's created during this festival.

Phil - Yes. They work in the recycling area. We have a recycle barn. We have planning permission to improve that facility now. We're going to make it larger and safer for people to work in because there's about 200 people working on that aspect of the site. So again, it's quite a large operation.

Ben - Well you said that you'd bring me to see the bins. I wasn't really looking forward to it. I have not got great experience of rubbish bins before, but this is incredible. It's a multi-coloured mountain of re-used oil drums. What's the story behind these bins?

Ben - Well you said that you'd bring me to see the bins. I wasn't really looking forward to it. I have not got great experience of rubbish bins before, but this is incredible. It's a multi-coloured mountain of re-used oil drums. What's the story behind these bins?

Georgie - Aren't they beautiful? It's a fellow called Hank and he has a team of 100 volunteers that come before the festival and they all paint them, each bin is unique with wonderful peace signs and invocations to recycle. They come back every year if there's more to be done and they work for their ticket by painting bins.

Ben - Do you know quite how much rubbish? There's a lot of bins here.

Georgie - A lot. There's a lot of rubbish. We try recycling it. We've recycled 50% last year and we're hoping to reduce the amount and recycle more next year.

Ben - So the important thing really is to try and get people to think about rubbish in a different way, because you're not just throwing it away into an ugly plastic or metal bin. These are things that people have put care and attention into to get you to think about your rubbish in a very different way.

Georgie - Yeah and it adds to the feeling of the site. They're very colourful and they're bright, and that's the sort of way that the Glastonbury Festival site looks.

Ben - So what's the next big challenge going to be for you? Clearly, dealing with all the planning permissions, the regulations for the reservoirs, have been a challenge to-date. What do you think is coming next?

Phil - Most certainly biodigestion. We've already got plans ahead for the solar panels on the farm roofs, but if we did have a biodigestion system working, and it was successful, we would be able to probably reduce some of the generators that are currently used onsite. It's high volume of generators, but then again, it's a very large site and a lot of people. So, if we can build up supplies of energy that we could tap into during the festival's period by selling back to the grid, you know, it would be great for us.

Ben - Infrastructure manager Phil Miller, explaining what's needed and Georgie Pope, showing me the sights and smells of the farm as it gears up towards the festival. Two million litres of reservoir and a capacity for almost 4 million gallons of human waste, it might sound like plenty. But this year's festival was exceptionally hot and sunny. The heat led people to drinking far more water than expected and this inevitably led to a greater volume of liquid waste. Without these reservoirs and the additional waste capacity, this year's festival would've had to be cancelled.

16:21 - Reduce, Reuse, Recycle - Green initiatives at Glastonbury

Reduce, Reuse, Recycle - Green initiatives at Glastonbury

with Lucy Brooking-Clark, Green Initiatives Coordinator, Glastonbury

Ben - The Glastonbury organisers pride themselves on doing as much possible to reduce their impact, not just on the farm itself, but on a global scale. Lucy Brooking Clark coordinates the festival's green initiatives.

Lucy - One of the biggest ones is Reduce, Reuse, Recycle. We give that message across in all the people that work for the festival, all the area organisers and all of the people that attend, the festival goers.

Lucy - One of the biggest ones is Reduce, Reuse, Recycle. We give that message across in all the people that work for the festival, all the area organisers and all of the people that attend, the festival goers.

Ben - This applies to, of course, everything; to water, to the actual materials that you use, the rubbish it creates. How can you keep a lid on this with such a dense population of people for such a short period of time?

Lucy - Well, yes, that is our ongoing challenge - through educating people, I think, because people come down and they don't realise the infrastructure that is setup for the festival, like the recycling operation that goes on. We're really trying to get the message to people not to bring unnecessary items to the festival because things are so cheap that they buy them then they think, "I don't need this anymore." And they just leave it on the farm and therefore, that makes a huge impact on the volume of rubbish that's collected afterwards, and to what the festival looks like. So through educating people that this is the same as being at home - in a sense that your rubbish has to be dealt with, it doesn't kind of get magicked away and go to some other place. It all has to be processed and just because you can recycle an item doesn't mean to say you should use lots of them. The idea here is to reuse first, reduce what you use and recycle at the end of the line.

Ben - Do you find that you have a lot of things that really should've been taken home that get left here at the end of the festival?

Lucy - Yes - lots and lots. Because the camping equipment is so cheap, you can pick up a tent, a roll mat, and a sleeping bag all for under 40 pounds. And when it comes to the Monday, when people are so spent of all their energy and they've partied hard for the last 5 days. They look at the things that they're going to prioritise and a tent just doesn't seem to have the value that it would have done 10 years ago or if you borrowed it from your Mum and Dad and you would have thought, "I've got return it." And people live in flats and their circumstances are different. They find an excuse not to take it and just go, "I'm going to leave it".

Ben - So what does happen to the things that people leave behind, either the things that can be used again or the real proper rubbish?

Lucy - Well it depends on what it is. It's amazing what we do find a use for. We have a problem with the chairs - a lot of chairs get left, the camping chairs. Whereas all the plastic gets stripped off those and the metal gets weighed in, so that does get recycled, the tents are a real problem because we can't find anything to do with the material. You can't melt it down, you can't reuse it. No one wants to take it. So that is something that unfortunately has to go to landfill. But everything else, all the surplus wood: that gets chipped up, either reused or chipped up for wood chippings, and then used across the site. The cans: they get weighed in. And the plastic: that gets recycled.

Ben - Is this all sorted on-site or do you have to ship it out somewhere?

Lucy - It's initially sorted on-site, so it's separated and then it gets taken and weighed in.

Ben - That brings me to another point about sustainability, which is transport. Lots of things have to be - lots of things and lots of people - have to be moved to and from the festival site. What are you doing to try and make that aspect more sustainable?

Lucy - Well we're trying to make us, as a festival, sustainable. So for instance the water - we used to truck the water on because we couldn't have it coming in through a maze, whereas now, we've got two reservoirs, each with a million litres of water. That means we've reduced truck movement there by not having that coming on and off. The sewage - we're going to process a lot more locally than we've had to before, which has gone 40 miles away. So it's looking at ways in which we can do away with vehicle movement. Transport of audiences is another big emissions factor to put on an event. We have a Greenbelt area and you've got a train station 15 minutes away, but we've got buses that come to the doorstep really, so we need to encourage people to come by public transport.

Ben - All of these things are put in place to try and make the festival more sustainable. Do you find that there's some overspill? Can you use the same things to make the farm itself more sustainable and even the area around the festival?

Lucy - Yeah. I think it has a very big impact on everything around. You have an impact on the people that come, making them think about it, and the farm. We're looking into an anaerobic digester which would mean that from all the produce that we have of slurry and grass cuttings, that could be used to create energy, and through solar panels on the roof of the cowshed. So things like that. It's looking at the resources around us and how we can get energy from them.

Ben - What's your next big plan? What your next big sustainability goal?

Lucy - We're hoping to get an anaerobic digester for the farm which takes the waste of the cows and the sewage from the cows, and the grass from the farm. You put it into a sealed unit, and through time it gets heated up and then it has lots of little bugs inside that eat away at it. And say you put a volume of waste of 100 litres in there, it reduces the volume and it comes out at about 10 litres. From that, you create heat as well so then you can get electricity from that as well. So, that's a really big plan for us. Obviously, financially, it's a big outlay, but it would help for our festival waste and for our farm waste.

Ben - So you'll be able to generate power throughout the year from the waste from the farm, as well as using the waste from the festival to add a bit more. How much power do you think you're likely to generate?

Lucy - We're being told it should be about a megawatt which is obviously a lot. We've got to look into that because we're slightly sceptical that it wouldn't be as much as that, but if it would: happy days!

Ben - Would you be able to sell the excess energy back to the grid in that case?

Lucy - Yes, we would. Yeah, we'd have excess energy, so we'd be able to run stuff, and we would have more to give back for them to buy.

22:51 - Playing with Recyclables

Playing with Recyclables

with Mark and Lorraine Cann

Ben - One example of recycled products coming full circle could be seen in the children's field where ship builders, Mark and Lorraine Cann were putting recycled plastic to good  use.

use.

Mark - You're looking at a child's play ship in the form of a double-ended tinner, made of steel and clad in Plastwood, which is a recycled product.

Ben - What's the advantage of using recycled plastic for this?

Lorraine - None, really. It's quite a difficult material to use, but it closes the loop with the festival. All the plastic from the festival goes into the recycled plastic and it's something that Michael Eavis wanted us to have a go at using.

23:34 - Making Festivals Sustainable

Making Festivals Sustainable

with Helen Heathfield, Julie's Bicycle

Ben - The entertainment industry has come under fire for hypocrisy with regards environmental sustainability, with some artists giving an environmental message whilst chartering private jets to travel from gig to gig. Julie's Bicycle was setup to help the creative industry reduce its environmental impact. Working with theatres, tour managers, orchestras and festivals, they evaluate impact and recommend how to improve sustainability. I spoke to Helen Heathfield, Associate Director of Energy and Environment, about how festivals compare with more traditional forms of entertainment  when it comes to sustainability.

when it comes to sustainability.

Helen - I think in many ways they have led it. I think because their environmental impacts are so visible - everybody can see the rubbish lying around in the arena at the end of the show and everybody can see the rubbish lying around in the camp site at the end of the festival. It's just so visible and I think also, a lot of people who are involved with festivals really do have a strong nature and earth-based approach to their lives anyway. Camping is one of the lowest impact ways of living, even if it's just for short time. So, I think a lot of people involved in running festivals do have a strong environmental ethos. And so, in many ways, the festivals have led on a range of initiatives around recycling and renewable energy, and just running their events in a more aware way.

Ben - How do you go about analysing the impact of something like a festival?

Helen - Basically, we collect data about energy, water, waste, and travel. So, energy is largely to with the diesel that's consumed in the generators onsite, though occasionally, rarely, a festival might actually be plugged into the grid. And then obviously, we also collect data about any renewables that they're using, any biodiesel that they're using, so that's energy. Then on waste, we collect information about the tons of waste that's going to landfill, that's going to recycling, and that's going to composting, and anything that's able to be re-used. For water, we're looking at the amount of water that's brought on site and then the amount of waste water that's going off from toilets and so on. And then finally with travel, it's a very vexed issue. At the moment, we ask the festival organises for any information they have about audience travel. And it's a tricky issue because it's not under the direct control of the festival organiser. They can put all kinds of infrastructure in place, they can charge for car parking. They can do all kinds of things but in the end, people will decide however they want to get into the site. So, we do ask for some bits of information about that if they have it. So those are the main areas that we focus on at the moment.

Ben - And what sort of data were you getting from Glastonbury? How do these things break down at Glastonbury?

Helen - Well, we haven't yet got the information for this year's festival. It often takes  a while for all the invoices to come through for diesel and waste, and water in particular. So I can't say anything yet about Glastonbury this year. What I can say of festivals in general is, audience travel is always the biggest impact, and just everybody getting to sites kind of swamps really the actual on site impacts. But then when you consider the energy, water, and waste, all of that diesel usage is normally the largest impact on site. And then any methane emissions from landfill are normally the second biggest, and then finally, any emissions from the water treatment is normally the smallest.

a while for all the invoices to come through for diesel and waste, and water in particular. So I can't say anything yet about Glastonbury this year. What I can say of festivals in general is, audience travel is always the biggest impact, and just everybody getting to sites kind of swamps really the actual on site impacts. But then when you consider the energy, water, and waste, all of that diesel usage is normally the largest impact on site. And then any methane emissions from landfill are normally the second biggest, and then finally, any emissions from the water treatment is normally the smallest.

Ben - I'm quite surprised really that people getting there is in fact the biggest impact. Castle Cary train station was absolutely packed. So obviously, a great deal of people had done their best to travel by bus or by train.

Helen - Yeah.

Ben - And the people I was speaking to at the festival, a lot of them had driven because of the convenience, and when you're taking your camping equipment, people do choose to drive. Do you think there's anything that festival organisers can do to try and discourage driving?

Helen - Yeah. A lot of them are already charging for car parking and also making a certain proportion of tickets tied to a coach journey, and making sure that those people actually do arrive on the coach. But obviously, carrying all of your tent, your camping material, your beer, your food, all that kind of stuff, across lots of different public transport interchanges and then across lots of different fields is, yeah, people feel it's inconvenient. So what we've seen some festivals do is providing pre-ordered beer onsite and we've also seeing some festivals providing a tent package onsite, your tents and sleeping bag, all that kind of thing. It's that kind of approach, trying to provide things for people on site so that they've got less to carry, and then they're happier to take the coach. There's also been some interesting initiatives where they've been seeking to make the coach part of the festival experience, having bands and other kinds of entertainment on the coach. So this really becomes part of the fun and we certainly found, two years ago now, we did some research on audience travel and we found that people who took the coaches really enjoyed it - they weren't expecting to and they enjoyed it more than they thought. So, I think people often have a rather fixed idea in their mind that the car is really convenient and the coaches aren't, whereas actually that isn't borne out by experience.

Ben - Obviously a large part of what you do is looking at how the entertainment industry can try and reduce its impact. Does the entertainment community have a responsibility to reduce their own impact, but also to encourage others?

Helen - It definitely has a responsibility to reduce its own emissions. So I think taking those actions to improve venues, improve festivals, and improve touring behaviour, is really, really crucial. And then once we start to see results and you know, there's reductions that we can claim and that are robust, the artist is obviously then in a much stronger position to be able to say, "This is what the industry has done, this is what I have asked for, this is what I've got, and so therefore, what are you, the audience going to do next?" I think there's something really important about tackling climate change which is about tackling this feeling of disconnection and being alone, and feeling powerless. And so, I think there's really important stories to tell about how we're in it together, we can all make reductions, and improvements together. And that it's just a lot more fun, I think, if we do do it together. That's a very important message for me and which I think the entertainment industry as a whole is in a very strong position to communicate.

31:24 - Greenpeace at Glastonbury

Greenpeace at Glastonbury

with Will Luton, Greenpeace

Ben - Many groups used the festival as a chance to communicate with the public and many of the issues they're communicating have a scientific topic at their core. But is a music festival really a good place to communicate science? I spoke to Will Luton. He was a volunteer with Green Peace who had a very visible presence at the festival.

Will - We are here very much to represent green issues. Green Peace's basis is formed around environment issues as well as peace and disarmament. We have a large campaign this year, focusing around palm oil and deforestation.

around environment issues as well as peace and disarmament. We have a large campaign this year, focusing around palm oil and deforestation.

Ben - The green issues that you have have at their heart, a scientific issue. What sort of priority do you give to communicating science with people or are you more engaged with the politics?

Will - Both of those things are extremely important for Green Peace and I don't think that you can separate one from the other very easily. All of our campaigns are led by science and the science leads hopefully to policy change.

Ben - And specifically, what are you doing here at the festival?

Will - Okay, so there's essentially a Green Peace Field where we have fun campaign things. So we have skate ramp down there, we have the rainforest showers. So, that's very much about communicating our campaign issues and our campaign agenda. We also have a presence backstage here, which is where we are now, where we are very much again communicating with people one-on-one and talking to people about what we do.

Ben - Do you think people are engaging with the issues?

Will - Yes, certainly. I've had some absolutely fantastic conversations with people. We've been pushing the fact that every 16 minutes, we lose a piece of land which is the size of the Glastonbury site in rainforest. That's every 16 minutes, which is absolutely huge and completely unsustainable, and people have been reacting to that. It's been really fantastic. I think people really want to get behind what we do.

Ben - This being the international year of biodiversity, do you think people are a bit more clued in to issues surrounding things like habitat loss?

Will - I think so, yeah. We had the conversations with people and we very much find that they said, "Did you do that thing last year? We've heard this thing about this other thing." I think people are very much aware of issues and becoming more and more aware. Particularly, habitat loss as well has been off the radar for a long time and it's been great to bring it back and tell people about it.

33:47 - Water Aid at Glastonbury

Water Aid at Glastonbury

with Melanie Tompkins

Melanie - Water Aid has been involved with Glastonbury since around 1994. It's a dual relationship. We provide a service at the festival. We man the latrines, we do the She-Pees, we do litter picking, and we also receive a donation back from Michael and Emily Eavis who are really, really strong supporters of us. It's a really brilliant place for us to campaign because people are very alive to the issues such as going to the toilet, getting something to drink. Because Water Aid is about helping the world's poorest people get access to safe water and sanitation, people have got a little bit of an insight to what it's like when things that you're used to aren't there, and you're struggling a little bit. At the moment, there are 884 million people in the world who don't have access to safe water and 2.6 billion that don't have something as simple as a toilet.

Ben - What are the problems that come from not having access to safe water and sanitation?

Melanie - The problems that come with not having safe water and sanitation, there are many layers to it. It's quite startling at the moment that 4,000 children die every day from a lack of safe water and sanitation - diarrheal diseases. That's more than AIDS, malaria and measles combined. And the problem with water fetching is that it's normally the girls who are tasked with having to get all the water so there are times when girls then miss out on education. They miss out in school because they're having to fetch the water. Obviously, health is a very big issue: if you're drinking dirty water, you're getting disease. Your health is bad but also, your ability to go out and work and earn money is also bad, as well as falling out of education. And there are things as simple as when a school has toilets, girls, especially around the age of puberty, are much, much more likely to actually go and get an education. So there are many layers to the reasons why safe water and sanitation are the very essential first steps of getting people out of poverty.

Ben - How do you find people are engaging with your message here?

Melanie - People really engage here. It's a really, really great space for it because the ethos of the festival is all about giving back and social justice and doing good. Of course, the fact that toilets are an issue here, maybe showering is an issue here and again, going to get water is an issue here - it's a really good combination for us. People are very open to it, they are very supportive and it's a really fantastic campaigning spot for us.

36:38 - Optimum Population Trust at Glastonbury

Optimum Population Trust at Glastonbury

with Ross McCloud, Optimal Population Trust

Ben - Lesser known groups also seize the opportunity to get their message out. Ross McCloud from the Optimum Population Trust...

Ross - The Optimum Population Trust is an organisation established to raise awareness about world population as an environmental issue. We just get the word out there that the world's population is full to bursting point, encourage contraception, and talking rationally - just having an educated debate about it really.

Ben - And what do you plan to get out of being at Glastonbury?

Ross - At Glastonbury, we're trying to raise awareness. We're offering condoms to all the young people at Glastonbury and trying to avoid unwanted, accidental pregnancies. But mainly, it's just making people aware that it is an issue and it's as big an environmental issue as any other.

Ross - At Glastonbury, we're trying to raise awareness. We're offering condoms to all the young people at Glastonbury and trying to avoid unwanted, accidental pregnancies. But mainly, it's just making people aware that it is an issue and it's as big an environmental issue as any other.

Ben - Offering condoms to people at the festival is a good way to try and avoid, as you say, unwanted pregnancies and possibly some teenage pregnancies, but population issues are a global problem, aren't they? It's not just our population we need to be thinking about?

Ross - They absolutely are, but what we're trying to get across to people here is that although the UK has got a birth rate of 1.8, we're consuming massively more than our own share of the world's resources. We produce 35 times as much CO2 as your average Bangladeshi and 160 times as much CO2 as your average Ethiopian. We need to take our share of the blame and we need to do something about it.

Ben - As developing countries become more developed, people tend to live longer and their consumption actually goes up. How can we as a developed nation advise or help developing nations to put a lid on the population before it becomes a problem?

Ross - Well, as healthcare improves in developing countries, we'd like to educate and empower women so that they understand they don't have to have as many children as they would have beforehand, when many might have died, and encourage them to be in control of their own fertility so that they're responsible for when they get pregnant, and it's their decision.

Ben - How do you get around some of the cultural issues that will get in the way of that - very male dominated societies or where you have had traditionally very large families?

Ross - The major things are to encourage education and empowerment of women. So, getting women in schools, young girls in schools, getting them a vote, and getting them a good, strong footing in society.

38:53 - Tackling Loss of Biodiversity

Tackling Loss of Biodiversity

with Michelle Osbourn, Somerset Wildlife Trust

Michelle - Somerset Wildlife Trust is one of 47 wildlife trusts across the UK. We're all individual charities but we all work collectively towards a "living landscape". We're trying to restore, recreate, and reconnect habitat across the country so that wildlife can thrive and people can feel alive again. We manage 82 nature reserves - we have over 300 volunteers who help us with that. We also run education programs, advocacy programs, trying to influence decision makers and make sure that wildlife is high up on the environmental agenda.

Ben - So, what are the challenges currently facing British wildlife?

Michelle - Well, wildlife is under threat from many quarters. Natural England produced a report this year which says that, on average, we are losing one or two species per year from this country, which is quite startling. We are on the brink of the 6th big extinction. Species are being lost at a phenomenal rate against what the baseline should be. In the UK, the threats are quite varied: habitat loss and fragmentation, development pressure, and pollution incidents are still a problem.

What we're trying to do to address that is to identify habitats that are still in good nick, buffer those as much as possible with habitat creation, and to start connecting them up linearly so that wildlife have highways - corridors so that they can move. The problem you get, once wildlife is isolated and on its own, it becomes very vulnerable to major events: disease, inbreeding as well, it's a bit of a problem. We need to make sure that wildlife can move around, especially in the face of climate change, because whatever happens here - whether we get warmer, whether we get colder - wildlife is going to have to change its geographic range. We've got to facilitate that movement and just get stuff moving.

Ben - This being the international year of biodiversity, are you seeing greater awareness in the public? Are people more tuned in to the sorts of issues that we're looking at?

Michelle - I wish that I could say, "Yes, they are." Climate change has moved up the agenda rapidly in the last 10 years. People are all switched on to renewable energy, but what they don't seem to be understanding is that sustainability, true sustainability, means looking after all facets of the environment. Biodiversity is the most fundamental bit of that. If we lose wildlife, if we lose that great big biological variety that we have, then our ecosystem starts to suffer. This is where everybody turns off now! But ecosystems' goods and services, things like soil fertility, crop pollination, fuel, clean air, clean water, all those things rely upon biological diversity. Without our wildlife, we're in trouble - we are in big trouble. A good statistic that I heard the other day from an eminent scientist is that one in every three mouthfuls of food that you take has involved a pollinating insect at some point. So if we lose our insects; no more food.

Ben - What are you doing here at Glastonbury? What do you plan to get out of being part of the festival?

Michelle - Well, what we're hoping to do today is just raise general awareness about wildlife and the issues facing wildlife. We're encouraging people to come in today and to visit our traditional cider orchard and to make a pledge for wildlife. What is the one thing that you could do to support local wildlife in your area? Could you volunteer for your Trust? Could you join you local wildlife Trust? Maybe you will say that you will only eat conversation grazed meat for example. There are all kinds of things that you can do. People tend to go for the obvious ones like having a wildlife garden, but think outside the box! You could create a pond in your window box, for example. There are all kinds of things that you can do to just do your little bit for wildlife and "green up" your patch.

Ben - And how do you think the festival goers here are taking it?

Michelle - Pretty well really. We've got a good range of activities. We're doing face painting for the kids and we're doing willow crafts as well, just to get them back to nature and using materials. People are loving the orchard. They're just going in and sitting down and, hopefully, having a real think about how they impact on biodiversity and what they can do to do their bit for it.

43:34 - Pedal-powered washing machine

Pedal-powered washing machine

with Alex Gadsden, Inventor

Alex - Hi. I'm Alex Gadsden, inventor of Cyclean which is a pedal-powered washing machine.

Ben - So how does this actually work?

Alex - Well straightforwardly, it's built by recycled components. It puts a bike together with a washing machine using the crucial part which is a hand-built, universal joint. Because the machine likes to move around and do its own thing, you've got to work with it - creating this universal joint cable gave it the flow and just made it work.

Ben - Electric washing machines are very energy-intensive, but spin at ridiculous rates. What sort of spin rate can you get from gearing up a bicycle.

Alex - Well, with the gearing we've got at the moment, we've got 520 rpm and that's on just a very easy spin cycle but if you really want to push it, you can get a 1,000 rpm out of it, no worries.

Ben - How clean does it get the clothes? Is it as good as using all the electricity?

Alex - Whiter than white!

45:05 - Science and the Spoken Word

Science and the Spoken Word

with Baba Brinkman, Hip-Hop artist

Baba - "That is often the idea that most enrages Darwin's detractors. And when I say Darwin's detractors, I'm specifically talking about his religious detractors like creationists. Not his scientific detractors. There are none. It's the idea that we, we came from ape-like ancestors..."

Baba - Hello. The name is Baba Brinkman from Vancouver, Canada and we are at the poetry and words tent at Glastonbury. Well in the set that I just did, it was a little bit of "The Rap Guide to Evolution" and some of the more rabble-rousing material with "I'm an African" and "Creationist Cousins". This always goes down pretty well because, as a spoken word piece, it's got quite a personal side to it. I also premiered my rap adaptation of the "Epic of Gilgamesh" which I've given a sort of the hip-hop/science treatment. I'm taking that to the Edinburgh fringe this year, and this was the first crowd that had heard it so I feel like it went down pretty well. I didn't know what to expect.

Ben - What do you think of Glastonbury as an event to talk about these sorts of things?

Baba - Well, I think Glastonbury is known as a big super rockstar headliner festival, but it is a festival of performing arts in all its guises. The poetry and word tent is a bit of a strange beast because it's that ecosystem without a real, locked, niche species that's holding it down. So the pioneer species drift through and some of them morph a little bit if they decide to stay, but you get a lot of randomness passing through this one for sure. It's like a Galapagos Island in a way.

47:25 - Performing at Glastonbury

Performing at Glastonbury

with Paloma Faith, Singer, song-writer, and actress

Paloma - Well it's the biggest festival and has the most attention so, I think it's the most widespread contact with your public that you can get of any festival in Britain. It's one of the biggest in the world, I think. There's TV exposure, radio exposure: the lot.

Ben - Do you think it's important for festivals to try and reduce their impact on the environment?

Paloma - Completely. But I think the fact that it's out in the countryside - and especially this year as the weather is so amazing - that automatically promotes care for the environment anyway because otherwise, we wouldn't have spaces like this to enjoy music here.

48:50 - Science and Politics at Glastonbury

Science and Politics at Glastonbury

with Josie Long, Comedian

Ben - Stand-up comedian Josie Long, performing in the cabaret tent, feels that politics and environmental messages have a strong root in Glastonbury.

Josie - I think it's definitely about politics. It's always been about politics. It's always been about ecology and about bringing people together on the left.

Ben - So do you think a music festival is a good venue to bring up those sorts of issues?

Josie - Well definitely. I mean, traditionally, you think about all the things that music has done. In the '80s, we had Rock Against Racism. They always went hand in hand. And protest songs in the '60s. Yeah, absolutely.

Ben - And moving on to more of the sort of scientific issues. Do you think it's important that festivals try and reduce their impact on the environment as well?

Josie - Oh yeah. God! Everything should. I think it's important that literally everything reduces its impact on the environment. I would go so far as to say it was essential!

Ben - You've been on record showing the strong interest in astronomy. How's that going?

Josie - I still have one. I'll tell you what I feel bad about is that I never get the time to go and do some star gazing which I would really like to do. I always tend to be in London and gigging, and missing out on things, so I don't get to do much practical astronomy. What I really like about astronomy is how much it's a good example of integrating science with a lot of other things. There's so much physics in it and you can relate it to lots of maths and things like that. It's also just about categorising and putting things in boxes, and working stuff out. I love that. It just is wonderful in the truest sense of the word; it just inspires you to wonder. It's fantastic and it's thinking about things which are gigantic and overwhelming, and looking at things which are beautiful. I appreciate that cell biology has some of that, you look it and you think, "Look at the patterns and stuff", but [astronomy is] brilliant.

Ben - Science is really part of our culture as well. Do you think there's a strong place for science at festivals like Glastonbury?

Josie - Yeah. I think especially in terms of, for instance, the Green Futures Field. It's really important to educate people who otherwise might not get to know about sustainable technologies, for example, and also about scepticism. That's quite important. Although it's a funny one, Glastonbury, because you've still got a lot of pretend healing and people saying, "I'll tell your future for 25 pounds." which I'm not sure I entirely approve of.

51:21 - Science as an Inspiration

Science as an Inspiration

with Robin Ince, Comedian

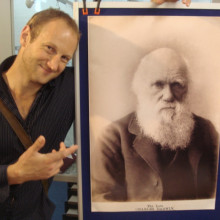

Ben - Broadcaster and comedian Robin Ince incorporates a great deal of science into his comedy, quoting from Carl Sagan, Charles Darwin and Richard Feynman among others in his sets. I asked him if he felt science could find a home at music festivals?

Robin - Well, I think it's all moving on a lot now. If you go back a few years, most music festivals were only two tents, and now, if you come to somewhere like Glastonbury or Latitude, or Bestival, or the Secret Garden, they've got lots of spoken word and other kinds of poetry and stand-up. And also, there are these great things which are breaking out where someone will say, "Do you want to go into a maze or into a forest and explain something to people?" I think it's probably Glastonbury that's quite a tough one because it is so enormous, but I can see that happening. For the show I do on Radio 4, Infinite Monkey Cage with Brian Cox, we're already talking about trying to do it at Glastonbury next year - taking over a comedy tent - and I think that would work really well. And I think also, sometimes now, there's so much music that people want a break and it's nice to go to sit down and allow ideas to waft over you and also waft into you as well. If they just waft over you, it's a disaster.

Ben - It's probably not premature to say that you're one of a frontline of people who are bringing science into popular culture, but at Glastonbury, it's a festival of performing arts. Do you think science actually has a place?

Robin - I think science could easily exist in the Glastonbury festival. I think you could start with the poetry and spoken word tent - it was very small a few years ago and it's got bigger and bigger. If you started just by having, say, three hours a day in one of the tents that became the science tent, I think people now, due to things like the Wonders of the Solar System and obviously, the Year of Darwin was a great way of getting things out and people are getting more and more into that. And obviously, with CERN and all of these things that are going on, people are really interested and I think they would come. If you put someone in a tent, if you got Brian Cox in a Tent, or Simon Singh, or Olivia Judson doing one of her pieces about the Sex Life of Animals, people will be interested. They'd come.

Ben - There's a lot of people here talking about the politics of issues that have, at their heart, a scientific problem. Water Aid are here, clearly the issues of clean water and sanitation are a scientific problem. Do you think there's too much focus on the politics?

Robin - It's very difficult when you say, "Is there too much focus on the politics?". What we need to do, I think, is to educate the people and the charities to get the science ideas out there. I did something at climate camp yesterday and obviously man made climate change a very big issue, and unfortunately, due to the nature of the media, we have a country where it seems to be 50/50 in terms of people who believe in it and people who don't. Mainly, it's arts graduates writing in newspapers saying it's all rubbish with no scientific backing. To work out a way of making palatable science communication about major issues is a very important thing to do. I think somewhere like here, if people could find out more than just the political angle in the "these children dying", but to get, "these are the solutions". Because that's a great thing that science gives - science doesn't merely say, "Look at the faces of starving or the collapse of infrastructure and the biosphere - all of these things." Science says, "And if we do this...", so it doesn't become a negative thing. Often, I think with some of these charities it is driven by the negativity in the tragedy. But [with science on board], as well as giving money, not only will we be able to [help], but if we get enough money, we can start really to work out a solution.

Ben - Do you think there's a risk of alienating people if you push the politics before the science?

Robin - When you watch something like Carl Sagan's Pale Blue Dot where he muses on this Mote of Dust suspended in a sunbeam - I think even if people just realised how tiny we are and that we are here, suspended in this obscure part of a not particularly impressive galaxy - that immediately gives you a focus in going, "Yeah, we've got one attempt on this, on getting it right". We're this tiny little lump of rock. There is no other known life as yet in the universe. We are the only example we know of of life in the universe. This makes it a very precarious thing. Why do the other 8 or 9 planets, whichever you prefer, in our solar system appear to have no traces of life on them? Why, when we ventured out further into the galaxy, are we not picking up any sense of life? That means it's not often happening. I think just to even focus - anyone who hasn't ever watched the Carl Sagan Pale Blue Dot clip that's on YouTube should look at it because I think that gives you more focus than even 100 marches.

Ben - When you first started weaving science into your comedy sets, it was mainly focused on scepticism. What are the things that are catching your interest now?

Robin - I started off obviously by talking about psychics and homeopathy and bunkum, new-age things. Now, I'm trying to focus more and more on the actual beauty of the ideas within science. So when you look at DNA and the system of replication, mutations - that to me is a very exciting thing. The moment that you think that every single human being and every single living thing on this planet is a mistake. I always like thinking that the great thing about DNA replication is that it's cack-handed. By being cack-handed, we have thumbs, we have eyes, we have ears, we have all of these things. Other beasts can see colours that we can't see, and you look at a tree and you think of the history of the tree that's led to that. So I'm trying to talk more and more about the passion behind it rather than the negative side: that it's a great pity that a lot of people believe in something with no rationalism or empiricism behind it.

Ben - And just lastly, have we just had a Glastonbury exclusive that we should expect Brian Cox here next year?

Robin - Well, I think Brian Cox will be on the pyramid stage. He will actually be suspended like a mote of dust in a sunbeam... It's quite incredible actually. I was with Brian Cox at the Cheltenham Science Festival and, since the last time we hung out anywhere in public like that, people just go, "It's Brian Cox! It's Brian Cox!" As a rockstar, he never became a famous rockstar. He's realised that physics should have always been the route to being the famous rockstar and I think what he does is fantastic. It is very much in a tradition of things that Carl Sagan's Cosmos which was a great influence on him. People watch Wonders of the Solar System and they do go, "Wow!". That's the great thing about science. I don't like using that term "wow factor" but there is. Every day, there's something I read or there's something I look at, or just looking at the sky and the sun, and I think, "This is incredible." This is what we need to instil into society. It really is absolutely wonderful that life exists in so many different ways, and what a pity that the one beast that has learned to live by altering the landscape may well be something that destroys, or doesn't destroy, the landscape. As George Carling said, whenever we talk about how we don't want to kill the earth: we won't kill the earth - we might kill ourselves, but there'll be other creatures that will still exist. It's just that they might not have self-consciousness. Maybe self-consciousness is a glitch.

Comments

Add a comment