Tens of thousands of Londoners developed painful, apple-sized, pus-filled boils before dying from the dreadful disease within days. But just as the ordeal of the Black Death seemed to be subsiding, the Great Fire struck the city. But did the conflagration actually save the lives of thousands? In this scorcher of a show, we go in search of the cause of the plague, explore the origins of the Great Fire, and ask whether history might repeat itself?

In this episode

01:13 - Cause or Cure? Treating the plague

Cause or Cure? Treating the plague

with Michelle Wallis, Cambridge University, History of Medicine

It's 1665 and London is a bustling, crowded metropolis. The cobbled streets, slippery with animal dung and slops, are narrow and full of people, and the stench of rotten food and sewage fills the air. Increasing numbers of people begin to fall ill with a disease known as the Black Death, and feared above any other. Michelle Wallis is a PhD student researching the history of medicine. She explained to Chris Smith what London would have looked like at the time of the plague, before putting our audience's 17th Century medical skills to the test...

Michelle - Well first of all, the red crosses were a big thing. You would look around your parish because this thing was sort of enlisted on a parish level and you would see the houses of your neighbours shut up. And you could see them in there having food passed in and know that they were dying and you would remember the last plague of 17 years before and you would see the dead carried out and just the atmosphere of fear, and everybody who could leave doing so, and leaving you behind.

Chris - What was it actually like in London at that time? How many people lived in the average house? What were conditions like to live in?

Michelle - For the poorer sort of people, lots and lots of overcrowding, and that was probably something that absolutely contributed to the plague. You would have large families pushed into very, very small dwellings.

Chris - When someone did die, what provisions were made for dealing with dead bodies?

Michelle - Not sufficient ones. Basically again, that was handled on the parish level. So basically, once your parish grave digger caught the plague or the clerks who record the death and the people who pick up the bodies, you just end up getting piles and piles of corpses that instead of being buried properly we might be thrown into a large pit with a small sprinkling of lime over them and they wait for the next one.

Chris - People in those times though had no concept of what disease really was, what caused disease or caused disease to spread. So, did they regard these bodies as an infectious disease threat or did they think only the living person was a disease threat?

Michelle - They absolutely regarded them as a threat. They had very different ideas about what caused disease but they absolutely had an idea of contagion. They just thought of the contagious thing, rather than being a bacteria as we think of it, as a bad air. If you think about it, corpses produce quite a lot of bad air. So, they were definitely seen as being a problem.

Chris - So, what was their concept then of what these bad airs were and how they spread and how the plague was getting around?

Michelle - Well, they were exhaled by people. You took them in through the pores of your skin. So, that's why you would smoke tobacco because that's a nice sweet, strong smelling thing that protect where you breathe. It's not just the people who had the plague who were shutting up their houses. People would voluntarily not nail the doors shut obviously, but keep all their doors and windows closed, light large fires, throw sweet-smelling things like herbs on those fires. And basically, if you saw like an object that you thought might be infected with plague, there's a great one in Defoe's Journal of a Plague Year - was a pocket watch they think was dropped by a plague victim. And they blow it up with gunpowder.

Chris - Well, timely. There were also reports of people doing things like - I mean, they regarded anything that someone had touched as potentially infectious. They would make people pass money through pots of vinegar or acid and things to cleanse it.

Michelle - Yes, absolutely. So, you can't think of a miasma just as in the way that we think of it.

Chris - Miasma is the stink that you're referring to.

Michelle - Yeah, the bad air. We would refer to as a miasma. But think of it as particles that cling to things. So for instance, they also definitely had a concept of it being transferred in cloth. Cloth is something that is often seen as a transmitter of plague and yes, money absolutely. And so, they would burn the belongings of people who died of plague.

Chris - Were there any doctors around who did epidemiology, the science of actually looking at how things spread around? Was anyone trying to work out at that time for academic or other reasons what was going on?

Michelle - To me, there's two questions there because epidemiology today is very much a question of statistics. They were obsessed with the statistics of the Black Death. Plastered up on walls, everywhere you looked would be posters that included the number of people who had been shut up or had died of plague.

Chris - So people were writing that down.

Michelle - Absolutely. we have very, very good records of that up until the point the parish clerk starts dying. But this is something people are very interested in. So not just the statistics of the current plague, but you would have in very, very cheap print that was put up on the walls everywhere and handed out in the streets, you would have list of the statistics for the last plague, for a plague that happened in the time of Queen Elizabeth. And then the question of physicians - what are physicians doing? Well, lots of things and 1665 is very interesting because there's been lots and lots of plagues in England before. But by this point, there are a couple of different strands of medicine kind of fighting for dominance in London and there's the established Royal College of Physicians who practiced what we called Galenic medicine which is about balance. And we have the Society of Chemical Physicians which is a little bit different and they're both trying to get you to take their drugs and use their methods.

Chris - It sounds like today.

Michelle - Yeah, a little bit like that.

Chris - I bet posting all these plague numbers on walls did wonders for morale.

Michelle - Well, it did when they started dropping! So, it's all about information. If you feel informed, you feel in control.

Chris - Is this why we have such a good insight into the history that you're relating to us because we've got those records?

Michelle - Yes, absolutely. We don't just have the records kept by the parishes themselves, but they were all collated at a central point every day. We have that in huge numbers, so we know exactly where the first plague case was in each outbreak, which parish it spread through first, which is how we can see how it fits with overcrowding, poorer areas, bad sanitation. Not that anywhere in London had good sanitation at this time, but yes.

Chris - Thank you very much, Michelle. Stay there because Ginny has got a little game in mind for us now. Ginny, what are you going to do?

Ginny - Well, now you know a little bit about how doctors try to treat the plague and how people believed it spread. We're going to play a game of Cause or Cure. So, I've got some items here on the table. What I want you guys to do is have a guess as to whether you thought that this item is something that back then they believed could cause the plague or at least make you more likely to get it or whether it's something that they thought could cure the plague or prevent you getting it if you didn't have it yet. What should we ask them about first?

Michelle - It's so hard to choose. Should we start with this one?

Ginny - Okay, so what we've got here is a pair of ballet shoes and that represents dancing. Dancing and leaping. I'm going to ask you if you think it's a cause or cure and I want you to cheer for which one you think it is. So, who thinks it's a cause? Who thinks it's a cure?

Audience - Clapping.

Ginny - Now, that's interesting. Well, I guess dancing, leaping exercise is quite a healthy thing we think of now. What do they think back then?

Michelle - They thought it opened the pores of your skin and let the plague in. So you're all wrong, sorry.

Ginny - So, no dancing if you want to stay safe from the plague. Now next, I've got a lovely bunch of rosemary which I picked from my garden this morning. So, who thinks that's a cause?

Audience - Few cheers.

Ginny - And who thinks rosemary could be a cure?

Audience - More cheers.

Ginny - So, that's a very strong smelling herb. So, I guess that was to prevent the miasmas from getting to you.

Michelle - Yeah and absolutely, it's a very popular one to burn inside your house.

Ginny - So, there were loads of different herbs that they thought were curative or preventative at least. What should we go for next? This is a slightly suspect looking, little vial of a sort of yellowish liquid. Can anyone guess what that might be?

Male - Urine.

Ginny - Urine, yes. Well, it's not. It's apple juice, but for the sake of today, we're going to say that's urine. It's actually special urine. It's urine from a healthy male virgin. So, who thinks that could be a cause of the plague?

Audience - No answer.

Ginny - No. Who thinks it could be a cure?

Audience - Clapping.

Ginny - So, what are we supposed to do with that?

Michelle - You're supposed to mix it with Venice treacle but it's a very expensive ingredient and it's not actually treacle. It also involves viper flesh, for instance, and with another sort of plague water and then you drink it, often.

Ginny - Anyone fancy trying it? No? No takers? What about some strawberries? They look a bit tastier. Who thinks they could be a cause?

Audience - Cheers.

Ginny - Who thinks they could be a cure?

Audience - Cheers.

Ginny - A split about 50/50 on that one so who's right?

Michelle - They are a cause. You should abstain from sweet fruits. If you must eat fruit, go for the sour ones.

Ginny - Smiley face. So, this is representing happiness. Who thinks happiness would be a cause of the plague?

Audience - Few cheers.

Ginny - Not sure on that one. Who thinks it would be a cure?

Audience - More cheers.

Ginny - What's the answer?

Michelle - Yes, you should try and keep happy as your friends and relatives are dying around you.

Ginny - So on the contrary, sadness was seen as, if you're sad, you're more likely to get the plague.

Michelle - Yes, absolutely. if you're sad, if you're melancholy, that's bad for your balance and you might die of the plague.

Ginny - Now, this is an interesting one. What I've got here is a collection of feathers. They're quite brightly coloured feathers. So, they're not necessarily a normal chicken but they are to represent a plucked chicken or pigeon.

Michelle - Preferably pigeon.

Ginny - So, who thinks a plucked chicken could be a cause of the plague?

Audience - Few cheers.

Ginny - And who thinks it could be a cure for the plague?

Audience - More cheers.

Ginny - We're about 50/50 again on that one.

Michelle - It's a cure. The question is, where is it plucked? And what do you do with it? You take a pigeon for preference and you pluck the feathers out around its bum and you put it bare bum side down on whatever blotches, whatever buboes, whatever swellings you have, whether they're in your neck, your armpit or your groin. And you leave it there for a while and it's supposed to draw the poison out. And so then basically, you remove said bare bummed pigeon and hope that it dies because if it dies, that means it's taken all the poison out.

Ginny - And if it doesn't die?

Michelle - Yeah, it's not good for you.

Ginny - Poor pigeon.

Michelle - Yeah, well hopefully.

Ginny - Okay, last two. We've got some dried figs and some walnuts. Now, this one looks a bit more appealing. Who thinks that's a cause?

Audience - Silent.

Ginny - Who thinks that's a cure?

Audience - Cheers.

Michelle - Yeah, you're absolutely right. There's a really popular recipe that they've put in the broadsheets I was talking about. For a fig that you cut it open and you put a herb called Rue in it and then you'll hold it in your mouth or close to your mouth or chew it when you go out of the house and expose yourself to danger.

Ginny - But isn't a fig quite a sweet fruit?

Michelle - Yeah. So, early modern medicine quite contradictory.

Ginny - And one final one, God. Who thinks God is the cause of the plague?

Audience - Few cheers.

Ginny - And who thinks God was the cure for the plague?

Audience - More cheers.

Ginny - Well, you're all right. Everything was put down to God.

Michelle - Absolutely. They went into all the stuff about bad airs and so on and so forth, but ultimately, you had to start praying.

Ginny - Fantastic! Thanks, Michelle and well done everyone. I think you all could probably go out now and be early modern doctors if you wanted to be.

13:38 - What was bubonic plague?

What was bubonic plague?

with Dr Luke Bedford, Addenbrooke's hospital, and Prof. Julian Parkhill, Sanger Institute

Thanks to scientific and archaeological investigations, we now know that the Great Plague, or Black Death, was probably caused by a bacterium called Yersinia pestis. It spread through flea bites, and also, possibly by people coughing and sneezing on each other. Later, Ginny Smith investigates how far a sneeze can spread germs, but first, we wanted to find out more about the bacteria that cause the plague. Luke Bedford, a clinical microbiologist at Addenbrooke's hospital, and Julian Parkhill who works at the Sanger Institute, also in Cambridge, told Chris Smith how you go about studying such an ancient outbreak...

Julian - We heard earlier that you often put plague victims into plague pits. We can recognise plague pits as large assemblage of corpses in the right time and we can carbon date those corpses and work out when they died. We can then extract the DNA from those bodies or from those bones, and identify the plague DNA inside them.

Chris - So, these bodies are still in London in big numbers and can be excavated.

Julian - Yes, definitely. We saw recently with the Crossrail excavations that they came across a large plague pit with large numbers of bodies from the plague. So, they're underneath us all the time, yes.

Chris - What sorts of tissues do you take from those bodies in order to get DNA from them because there's not much left? I mean, they're just skeletons, aren't they?

Julian - Actually, the best place to get plague DNA is from inside teeth. The pulp of the teeth is where the blood collects and plague grows to very, very large numbers in the blood. so, there's some plague DNA left inside the teeth and it's kept protected from the rest of the soil and it's possible to get the DNA out from the inside of the teeth.

Chris - So, archaeologists come along - well, Crossrail come along, they dig up some bodies. Archaeologists come along, they get some bits of those bodies, they get teeth, they drill holes in them rather like the dentist, and get DNA from the person plus the bug that they died from. That's your interpretation, is it? The bug they died from is in there and you can then extract the DNA to study it.

Julian - Yeah. The bug they died from is in there, but there's also an enormous amount of other DNA - bits and bits of their DNA, bits of soil bacteria, mostly modern soil bacteria. So you have to know what you're looking for and you have to go and fish it out. If you know from modern sequences, from modern DNA, what plague DNA looks like, you can go pull out those bits of DNA directly from the mixture that's in that tooth.

Chris - So, that's how you did it. You had an idea that this could've been Yersinia pestis -this bacterium that could've been linked to the plague. And you said, "Well, if that was the cause then the genetic signature Yersinia pestis might be in the DNA extracted from these teeth and hey presto! You go looking and it's there."

Julian - Yes, so this was the first time a group in Germany - not actually the Sanger, but that's exactly what they did. They said, "We believe that this may have been caused by Yersinia pestis. These are victims of the plague. Can we go and find Yersinia pestis DNA in there?" And they did, yes.

Chris - Now, we actually have an idea that it really was Yersinia pestis - the bacterium - that caused the plague. Let's find out from Luke what this bug actually is. So, paint a picture of Yersinia for us.

Luke - Yersinia pestis is a single-celled organism, a bacterium. Primarily, they live in fleas, and rodents. And that's how they spread around in the wild, so to speak. And they do that by taking blood meals from rodents, and other mammals, and then when they take another blood meal, they regurgitate. The bacteria actually makes them regurgitate - through a set of genes that it's got - over into the wounds that they've just created, and that's how you tend to get it spread from person to person, it can do, and from animal to person and from animal to animal with the reservoirs in the wild. From there, it can travel and start to cause disease. Once it gets inside the body, it starts to develop, it changes the proteins that it makes and becomes resistant, to a certain extent, to the body's mechanisms of fighting off the phagocytes and other immune cells. It then travels to lymph nodes, and this is where we see the clinical picture of bubonic plague from. So, you get these massive and large painful tender lymph nodes in the groin...

Chris - These are your glands, aren't they?

Luke - Yeah. When you feel your glands raised, it's because you might have a bit of an infection. But when you've got bubonic plague, they're huge, they're painful and they're very nasty.

Chris - Is that because the bug has gone from the bite? It's replicating, or growing, at the wound site and then it's spreading through the body to those glands or lymph nodes and then causing them to swell up. Is that the reason?

Luke - Absolutely. They sort of hitch a ride, so to speak, in the immune cells of the body and gets carried and concentrated in those lymph nodes.

Chris - So, the immune system sort of helps it around the body.

Luke - Yeah. The Yersinia pestis bacteria have got a way of protecting themselves from the immune system of the body, from these phagocytes, that ingest them. From there, they have a capacity to then be carried into these lymph nodes where they can multiply and from then on, spread through the blood into other parts of the body as well.

Chris - Once you've got that condition, is it "curtains" for you? I mean, what happens? How does it make the person ill?

Luke - It makes the person ill by doing a few things. In the blood, it produces all sorts of proteins and enzymes and what it can do is make your blood very thick and coaguable. And what happens is when that affects the distal parts of your body, your fingers and toes, the small arteries in there, you get gangrene, which is where we get some of the terminology...

Chris - Black Death - yeah, because these bits are going to go black and drop off, aren't they?

Luke - That's septicaemic plague, and the other type of course is pneumonic plague, which is what we imagine with these coughing, sort of pestilent plague victims who were wandering around. And that is very bad news as well.

Chris - So, that's the plague in your lungs and you can cough it out. You don't need a flea. You can cough it out and if I cough on Julian, he's going to catch it...?

Luke - Yeah. It's much less likely to - at least there's a lot less cases - particularly these days, of primary pneumonic plague which is where it spreads like that, but it does happen.

Chris - Does that mean then that once you've got your fleas giving some people plague then people can give it to each other via that aerosol route? So, it can start off as that bubonic plague, from a flea bite, but then other cases can occur with the spread via the respiratory route?

Luke - Yeah, absolutely. so, that can be another mechanism by where it spreads. I guess perhaps in older times, you would get more - because there were so many fleas about, you would still get a lot of transmission. But these days, with less of a flea population in people, we assume, depending what the population is of course, you're going to get more pneumonic spread.

Chris - Can it be treated?

Luke - Yes. There's many effective antibiotics available and actually, if you catch bubonic plague now, you've got a pretty good chance of surviving. Around about 10 per cent of people who have plague these days - we think - die. But obviously, case ascertainment - where you have most of the plague - is sometimes quite difficult.

Chris - How many cases are there today?

Luke - In the UK, there's none. We haven't had any cases I believe since the 1930s in the UK. You still do get cases in the west of America for example and sub-Saharan Africa. But generally, we're talking about a couple of thousand a year I believe.

Chris - So, nothing on the scale of what happened in the 1600s during the Black Death?

Luke - No.

Chris - So Julian, what can you tell us about your genetic investigations then? What did you find when you studied the DNA of the plague victims that you've said they had Yersinia there? Is it the same bug that Luke is describing is still causing cases today?

Julian - Yes. When we first sequenced Yersinia, when we first generated the genome of Yersinia, it was actually with a modern strain rather than an ancient one. And what we were able to see was how this organism had evolved. It's a very recent organism. So, we're talking about the plague in the 1600s, but plague probably evolved only a few thousand years ago. And it used to be an organism called Yersinia pseudotuberculosis. Yersinia pseudotuberculosis causes enteritis, a kind of diarrhoeal disease in humans. It's a mild disease and it also causes a diarrhoeal disease in fleas. So, it infects mammals like rodents and it infects fleas.

Chris - The mind boggles with the prospect of a flea with diarrhoea! But do go on.

Julian - A very careful experiment I think you have to do there. So, what Yersinia pestis did was it found a way to jump, to change from going through a faecal-oral-diarrhoeal route in fleas and a faecal-oral-diarrhoeal route in mammals. To suddenly connect the two it only required one or two extra genes to do that. And if you look in the genome, if you look at all the genes it's got, then it's got all the genes that it needs to cause the disease we know about now. It's still got all the genes in there that it used to use to cause diarrhoea in humans. And they're still all there. They're just knocked out. They're inactivated. So, by looking at the genome, you can understand how it evolved, where it came from, and how it changed.

Chris - Can you answer the big question which is probably the crucial one though which is, if it's so similar today to the strain that was causing the Black Death, why did so many people die in the 1600s, yet today, it's only a handful?

Julian - No. Unfortunately, we can't answer that question. We can study very large numbers of plague organisms now and we can look at the diversity of plague and we can use that to reconstruct where it comes from and it's very clear that plague is endemic and it's common in China. It circulates in rodents and around there in China. And it has come out of China and caused at least three plagues: The Justinian plague before, the one we're talking about, the Black Death, and then another plague in the 19th century. So it's continuously evolving in China and it's come out of China multiple times to cause pandemics. Now, because of the way that the ancient DNA was sequenced - because the people who did that took what we know about plague now and used to fish out what was there - we can't say that there wasn't anything new, anything we don't know about. We can find out what we know about. We can't say there isn't anything in that genome in the ancient plague that we didn't know about. But it looks very much like it's the same organism causing the same disease.

Chris - So, there might still be something else that was in circulation at the same time. We'll just have to wait and see I suppose. Julian Parkhill from the Sanger Institute and Luke Bedford from Addenbrooke's Hospital, thank you both very much.

Ginny - One theory is that the Black Death in 1665 spread so rapidly because this pneumonic version became more prevalent. And as you've probably experienced with colds and flu, and that sort of thing, things that spread by coughs and sneezes spread very quickly and very easily through homes and through schools. And that's because when you sneeze, the amount of virus or bacteria that's coming out of you is huge and it can go quite a distance. So, I've got a slightly, well hopefully, not too disgusting because I'm not actually going to be sneezing. Well, what we're going to do now is recreate some sneezes using this spray bottle and look at how you might be able to stop them spreading. So, I'm going to someone to come up and do the sneezing for me. Who wants to do that? What's your name?

Peo - Peo.

Ginny - Peo, great! If you just hold that bottle for me. What I'm going to do is I'm going to put a big sheet of paper out on the floor. Don't squeeze it yet and not when it's pointed at me, okay. Okay, so I've got a big sheet of paper here on the floor. If you sort of crouch down for me and put the bottle right at the edge of the paper and then when I say go, I want you to give it one nice big squeeze and we'll see how far the droplets go. Okay, ready? 3, 2, 1, go! Can you see the droplets on the paper?

Peo - Yes.

Ginny - So, how far have they gone?

Peo - Almost all the way to the end. In fact, you can see a tiny drop just at the end.

Ginny - Okay, so we've got about a metre and a bit of paper there and the droplets have gone quite a long way. What's interesting is you can also see that there are some big droplets and there are some really tiny little droplets. And that's the same with the real sneeze. They're the kind of big globules of spit and snot that come out that you might be able to see. But you're actually spraying out tons of tiny weeny particles and there was some research that came out a little while ago that actually said that we used to think they could go maybe a few metres. But these tiny little particles can actually get picked up by air currents and go a lot further, 200 times further than we previously thought. And that's far enough to infect everyone in this room definitely. So, what can you do when you sneeze to try and stop yourself from infecting other people?

Peo - You cover your nose.

Ginny - You can cover your nose and mouth, exactly. So, that's what we're going to try next. We've turned the paper over so we've got a clean side and we're going to try covering it with my hand. So, that's what a lot of people do when they sneeze, isn't it? You put your hand in front of your mouth. So, I'm going to put my hand. Where do you put it? Kind of a few centimetres in front of your nose and then I'm going to countdown again and I want you to spray. Do you think I'm going to block all of it or do you think we'll see some of it on the paper?

Peo - I think we'll see some.

Ginny - Let's have a look, shall we? Here we go, 3, 2,1, go! There's a lot of purple die on my hand so I did manage to block quite a lot of it. What can you see on the paper?

Peo - There are a few tiny droplets in the middle of paper. At least it didn't reach the end this time.

Ginny - That's true. So, it's better, isn't it? A lot of the big droplets, I've caught. But if you look closely, there's actually quite a lot of the tiny weeny little droplets that have got through. And also, now have a think about what's on my hand. What am I going to do now? When you've sneezed, do you always go and wash your hands straight away or do you sometimes pick up a pen or go and shake hands with someone? Would you want to shake hands with me after that? No.

Female - My mummy always says that if we sneeze or cough by our elbow then we won't put it on our hand and it's less likely to spread.

Ginny - Exactly because how often do you pick up a pen with your elbow? Not very often.so actually, that is now what people suggest that you sneeze into the sort of crook of your elbow, the inside of your arm. What that'll do is it'll make it less likely that you pass on the disease. The other thing you can do is you can use a tissue. A tissue is a bit bigger than your hand. So, we're going to try that now, last try and I've got another clean sheet of paper. This time, we're going to put the tissue right in front of the spray bottle and see what that does. Ready, Peo? 3, 2, 1. How's my paper looking?

Peo - Completely white and the tissue is looking very purple.

Ginny - There's a big gross purple splodge on the tissue but I can see - there's one tiny weeny drop there, but I think that's it. So, tissues are great because now, what I can do is just ball that up, chuck it in the bin and the infection is gone. If you don't have a tissue, the crook of your arm is the next best thing because really, you don't want to be sneezing on your hand because you use your hands a lot. But this just shows quite how fast sneezes can spread. It's not really surprising that if you had lots of people living in cramped conditions sneezing on each other, it didn't go well.

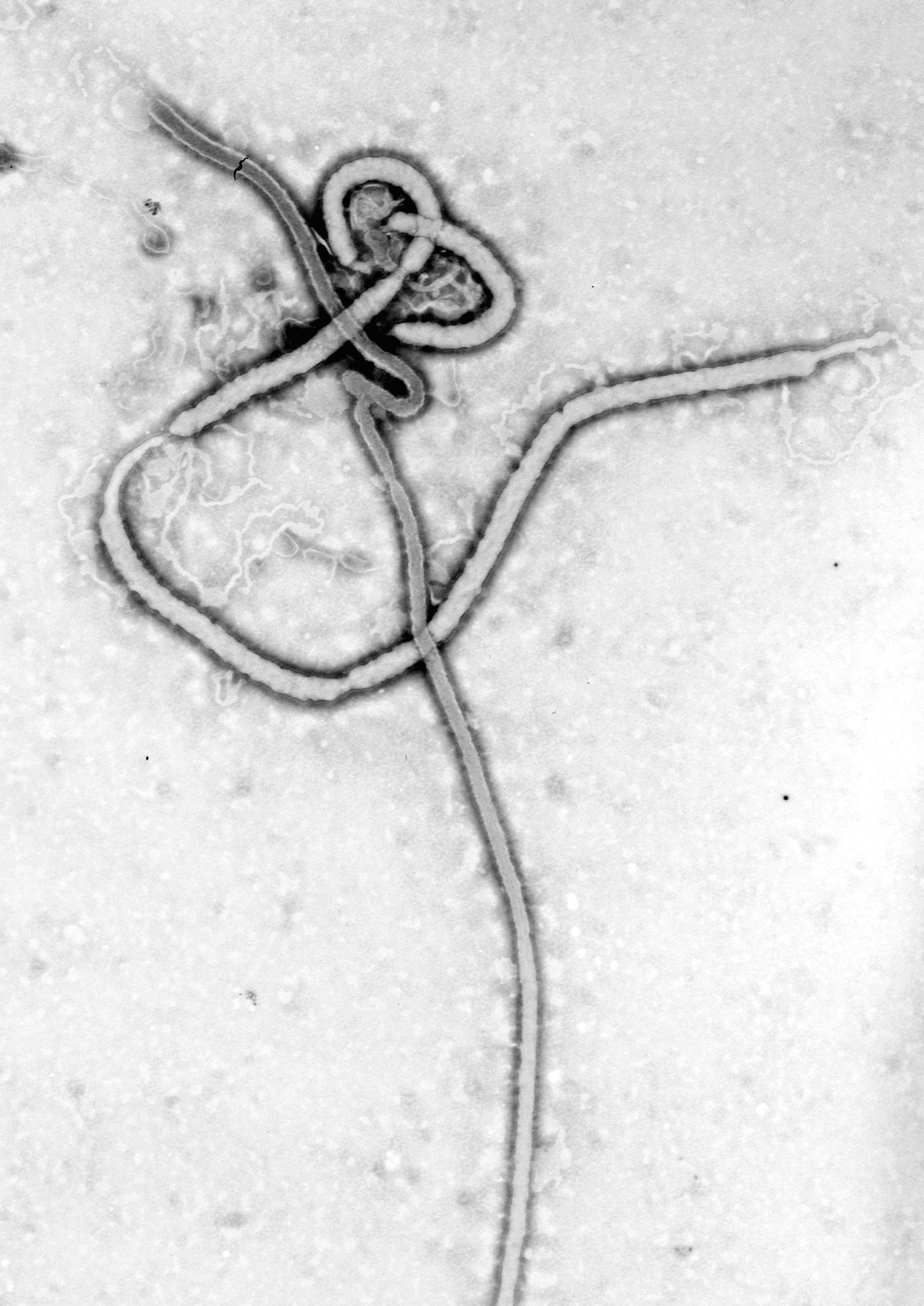

30:29 - Modern plagues: Ebola

Modern plagues: Ebola

with Dr Kevin Wing, Cambridge University Department of Medicine and The London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine

Unfortunately, while Yersinia pestis may now be more-or-less under control, there are other diseases around today that have similarly devastating effects, particularly in developing countries, which have the same overcrowding and sanitation issues London faced in the 17th Century. One 'modern plague' that has been in the headlines a lot recently is Ebola. Dr Kevin Wing works at the Cambridge University Department of Medicine and The London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, and recently spent time working at an Ebola Treatment Centre in Sierra Leone. He explained to Chris Smith why the recent epidemic was so dramatic...

Cambridge University Department of Medicine and The London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, and recently spent time working at an Ebola Treatment Centre in Sierra Leone. He explained to Chris Smith why the recent epidemic was so dramatic...

Kevin - In the recent outbreak, the key point was that the countries where it was especially bad had very weak health systems. So, the infrastructure that was there was not able to cope with such an outbreak in any way.

Chris - And that's the crux of it because you've just got a very poor country, very poor health services, and there's a big opportunity for diseases to just escape.

Kevin - Well, I think if you look at some of the other countries that Ebola did go to apart from Sierra Leone, Guinea and Liberia, you can see that there was only ever a few cases in those other countries. For example, I think Mali had two cases and there was one case in Nigeria. The reason that it didn't spread in the same way was because those countries had health systems that were more able to cope.

Chris - Your feeling then is that if we look at what happened with Ebola in countries like Sierra Leone, this is a pretty good proxy of what was probably going on in London to an extent during things like the Black Death.

Kevin - Yeah, absolutely. I think when Ebola hit Sierra Leone for example, there was a real problem and in fact, there still is in actually persuading a lot of Sierra Leoneans that Ebola was real. Obviously, with the coverage that we get in the media here, that sounds incredible but it really was a problem where you've got culturally and very engrained practices and beliefs. And also, suspicion of people coming in and sort of dictating. So, it was a very, very sensitive management at the beginning of the outbreak.

Chris - People have done analyses of what they think the recipe is behind the sort of disaster that was Ebola because we first discovered Ebola more than 40 years ago. In the entire time since then it's killed fewer people than it did in this one outbreak. So, people were obviously asking, "Why here? why now? Why has Ebola done this?" Some have suggested actually, it's because of population. There are more people around and there are more mobile people around.

Kevin - Yeah, well I think again, taking Sierra Leone as an example, when it entered the country, there was an initial - I think it was actually a funeral of the traditional healer and from that one funeral, there was something like 300 cases. And then it spread across rural areas relatively quickly and it was very difficult to trace in those rural areas. But the big concern was that what would happen when it got to the capital, Freetown. In fact, it was in Freetown where there's a very high density of housing and people living in close quarters that it really exploded. There's a huge number of cases that came from the capital.

Chris - This week, at the beginning, we were hearing about things that people believed were causes and cures of the original plague Yersinia pestis. Ebola is obviously a virus. It's a little bit different but are people similarly misinformed in Africa and that's part of the problem with dealing with how you stop it.

Kevin - Well, I think at the beginning of the outbreak, it was very difficult to get the communication across. In fact, it was a rainy season for example and being able to set up and communicate actually what was happening, and getting health education across is very difficult. And the particular issue is that one of the traditional practices is to wash the bodies of people who've died at funerals. In fact, dead bodies are secreting the highest amount of virus. In fact, that's the most infective situation. But it's very difficult to get people to try and change that behaviour and very upsetting as well for people not to be able to watch their loved one.

Chris - I think it's worse than just washing. They were washing and drinking the water they wash the bodies with, weren't they?

Kevin - Yeah, absolutely. This behaviour, it's very difficult to change and we've heard already about having the plague that the burial was very important in the same way for Ebola. The burial practices were really key - once you get those changed, that's a big step.

Chris - What can we do with modern science in the modern era to try to prevent Ebola, but things like Ebola as well coming back and doing this to us again?

Kevin - It's interesting because when people think of sub-Saharan Africa, they think of - well at the moment obviously, they think of Ebola, but they think of other infectious diseases such as HIV, tuberculosis and malaria. And in fact, what the big challenge that sub-Saharan Africa is facing now and will face, and we don't hear so much about is actually from diseases that are not infectious. So, this is the so-called non-communicable diseases. What I mean by that is diseases such as diabetes, cardiovascular diseases and respiratory diseases. And in fact, by 2030, it's predicted that the deaths from those diseases will be greater than the deaths that traditionally are the leading causes of death in Africa such as infectious diseases, under-nutrition and maternal and perinatal death.

Chris - One of the things that got highlighted in my view, a bit late in the Ebola story though was that: along comes this virus and it decimates the healthcare system which was already pretty feeble. And that meant that there's now nowhere for a woman to go and have a baby with any degree of safety. There's nowhere for anyone to get any treatment whatsoever for a common disease like malaria or a flare-up of TB. So, you have one outbreak of one disease that then causes a snowball effect, destroying lots of other lives through other consequences.

Kevin - Yeah, absolutely. I mean, the solution for that is obviously very difficult in these countries which are very resource poor and do not have effective health systems. But I think going back to my point about non-communicable diseases, in other African countries, if we don't get a handle on these non-communicable diseases such as diabetes and heart disease. Then in fact, the health systems that are already working are going to be under so much pressure that something like the outbreak we've seen could happen again.

Chris - What about the world as a whole, because many people say there's so many of us on Earth now and we're so mobile that we really are cruising for a biological bruising? Because we've got up in the air right now around the planet, a million people aboard airplanes. No cities more than 24 hours from any other city which is inside the incubation period of most infectious diseases. So unlike when the great Black Death plagues were knocking around, people had to go everywhere, they were going to go by boat and it took them months. Now, you can be on the other side of the world and spreading a disease before you even know you've caught the disease.

Kevin - Yeah. That is something that came up in the media a lot. In fact, I think during the outbreak, the international community really only got involved when those concerns came up which was obviously a tragedy for the countries involved. But I think that people are always going to want to travel and the way that we live is the way we live for better or worse, but what we really need to focus on is looking at the burden of disease in these countries and more and more of that is these non-infectious diseases and looking at research to help handle those so that then we're in a position to help with infectious diseases that emerge.

Chris - Kevin Wing, thank you very much.

Ginny - One of the factors that has a huge impact on the spread of disease is population density. So the more people you have packed together, the faster a disease can spread and that was one of the big problems with this outbreak of the plague. So, I have a little demo here to show you how that works and it involves cake. So, I have two cakes here and they're going to represent our two different kinds of population. On the left hand cake, there are 8 candles and those represent people. On that cake, they're very crunched together. They're all up one end of the cake. They're very close together. On the other one, we've got the same number of candles, but they're nicely spread-out. Now what we're going to do is light one candle at each end of the cake and that's going to represent someone catching a disease and we're going and watch and see if that disease starts to spread. And if so, in which cake it spreads more quickly. So, I've now got one candle lit at each end and I've just got a fan here and I'm just very gently fanning the two cakes. So, who can see something happening?

Audience member - On the cake where the candles are really bunched up, it's spreading and on the one where they're spread out, it's not spreading at all.

Ginny - Exactly. So, I've now actually got three candles lit on the cake where the candles which are representing our people remember, are very closely packed because what's happening is, as I'm fanning the flames, they're sort of moving around a little bit and they're jumping from one person to the next or from one candle to the next. They're now all lit, whereas on the other one, which I've just started fanning a bit more because it wasn't doing anything, I've now managed to blow out the first candle which is quite representative actually because if there's one person infected, they're going to either recover or they're going to die. But if there's no one else around them for them to infect, that's where the disease ends. And that cake now has not a single candle lit on it whereas the other one where they were close together and the infection could jump from one to the other, they're now all lit. This is a really interesting demo because not only does it model the spread of infection. It actually also links very nicely to what we're going to talk about next which is the great fire of London.

40:12 - London's burning: the Great Fire

London's burning: the Great Fire

with Dr James Campbell, Cambridge University’s Department of Architecture

After starting in a bakery, the Great Fire of London burned for four days, destroying huge areas of the city. Just as infections spread swiftly through crowded areas, the tightly packed houses allowed the fire to travel rapidly. James Campbell is an architect and architectural historian who studies this period. He explained to Chris Smith what London would have looked like at the time of the fire and how the fire changed the face of the London we have today...

areas of the city. Just as infections spread swiftly through crowded areas, the tightly packed houses allowed the fire to travel rapidly. James Campbell is an architect and architectural historian who studies this period. He explained to Chris Smith what London would have looked like at the time of the fire and how the fire changed the face of the London we have today...

James - You've got to imagine - we do have some of these kind of buildings still surviving - timber frame buildings. They're tall. They're 3 or 4 stories on the big streets and many buildings behind them tightly packed down small alley ways. These timber frame buildings have wattle and daub basket weave and plaster as a front. So, they will burn extremely easily.

Chris - How many people would've been living like that? How big was London at that time?

James - Well, it was a lot smaller than modern London. Of course, after the plague, there were many fewer people. But we're talking of a city of about 140,000 in the city and then more in the suburbs. But at this time, the suburbs don't stretch very far. Hampstead is still very much a village in the countryside.

Chris - Were fires terribly common at that time? Or had no one really seen a disaster on this scale before?

James - There had never been a disaster on this scale, but fires were common in towns throughout England in this period. But commonly, they only destroy 30 or 40 houses and the only method of firefighting was to pull the houses down in front of the flames so they had hooks and crowbars and things, and they literally demolished the houses.

Chris - Was there a fire service? Today, we dial 999 if we see a fire. Was there any equivalent then?

James - No, not at all. It was reliant on small organisations, parishes to have their own firefighting equipment and that was part of the big problem of course.

Chris - So, there was no sort of joined up system, no one you could rely on to come in an emergency.

James - And often, as happened in this fire, everybody was so busy saving their own property and running away from the fire, that they wouldn't help out anybody else.

Chris - What was the scale of the damage? We've heard obviously Pepys saying there were hundreds of houses, but what was the eventual outcome of the fire?

James - It was completely a disaster. So, it starts in Thomas Farriner's shop, he makes biscuits of all things, and it catches very quickly.

Chris - How do we know it started there?

James - Because there's a large court case afterwards and he admits that it started in his baker's shop and he clambered out over the roof. Unfortunately, the first casualty of the fire was his maid who was too afraid to cross the roof and escape. Remarkably in this fire which destroyed 13,200 houses and 87 churches, remarkably, only 6 people died which is extraordinary. And they all fled, with what possessions they could carry, to the fields around London and for 4 days, they were camped in tents around London.

Chris - Is that how long it burned for, 4 days?

James - It burnt for 4 days. They were still there 4 days after the fire had died down. It just kept burning because it had been a long hot summer. Everything was tinder dry and there was a nice wind blowing in from across the Thames going westwards.

Chris - Quite literally a perfect storm this, wasn't it? Did it make its own weather as well? Because when we've seen examples of fire storms in world war II where lots of ordnance was dropped on a city in Germany for example, there were classic cases of this, you end up with a fire that's so hot, so intense, that it's pulling in so much air it creates an apparent wind that then drives the fire even faster.

James - We don't have descriptions, though we can guess that that must've been what was happening. It was certainly extremely hot, so that it, for instance, catches St. Paul's Cathedral which is a big stone building and wasn't expected to burn, just because there were so many tinders and things flying through the air. And it's only stopped eventually by the king blowing up a large area of London to the west of it and the weather changing. And that means that everything dies down.

Chris - They create a firebreak by literally just wiping out all the potential fuel.

James - They blow it up and they have done the same thing around the Tower of London and this just created an enormous firebreak.

Chris - How enormous?

James - A hundred meter-wide firebreak approximately.

Chris - That's a lot of houses, isn't it? And all these people who end up camped out on the fields, what happened to them?

James - Well remarkably, they found lodgings in the next few days. But then of course, they had to rebuild. When we were talking about this overcrowding, this is then when this problem is solved. Firstly of course because nobody is living in the city at all for several years. Really, the building isn't completed until about 1672. So, you've got quite a long stretch where there's very few people moving back into the city. And then by new building regulations which change the way they build. So, gone are the higgledy-piggledy timber structures which are cantilevering over the roads ,so they jetty out and they almost meet in the middle. You can imagine how good that was for spreading disease and also for fire. And now, you can only build straight, upright, brick buildings with no exposed timber work. So, we get the city which we're so used to with rectangular windows and brick arches.

Chris - This is the origin of the building regulations that plague us today. It's the Great Fire of London to thank for that.

James - If you think of building regulations as a plague Chris, yes. Yes, that's true. This is the origin of the brick built city. It's not a hygienic city. The sewers and things will come much later, but it's a city where they get away from the overcrowding in the back alleys because they say "you can't build very high in back alleys. You can only build high on big wide streets. The narrower the street, the lower you can build, and everything must be in brick."

Chris - You said that it sorted out a lot of the problems, but didn't sort out all of them. There was quite a notable exception of the sewer situation. So, what was life like in London post-fire before the sewers came along?

James - Well, the water came out of the Thames or it came out of streams running down or it came out of wells. The problem is, your sewage went into pits or tanks behind your property and then it was emptied out periodically by people who were employed to do that. Of course, you had basements. That was one thing that came in. And so, very often these pits which held the sewage would leak into the basements. So, you could get whole basements full of sewage and not to mention of course, also into the water supply, which is why in the 17th century, most people drank beer to avoid poisoning from water. It's really only in the 19th century when the sewage problem gets dealt with in London because the sewage is also going into the Thames. So, your water is coming partly from the Thames, your sewage is going into the Thames, and so, as you can imagine, it's a source of disease.

Chris - I suppose we exchanged one plague for another because then that meant things like cholera became much more common. Is it a myth that the great fire wiped out the plague? Is that true or is that just apocryphal?

James - The plague had already died down by the time the fire hit. But there is no doubt that if you wanted to completely destroy any vestiges of rats or fleas or anything else then the great fire really did it because it completely flattened everything. And it kept smouldering for weeks, although it started to rain along last and that gradually put the embers out. So people, wandering around the city in the days afterwards described this terrible wasteland of still burning buildings.

Chris - James Campbell from Cambridge University, thank you very much.

Ginny - We know that the great fire started in a bakery and modern bakeries are still surprisingly dangerous places to work. So while open fires are less of a problem, the products they work with like flour and icing sugar can actually be a danger in themselves. And that's because finely ground substances combust or burn at a much lower temperature than they would if they weren't so finely ground because they're so mixed with the air. And of course, oxygen is one of the things that you need in order to set something on fire. In fact, with some substances, the spark you get when taking off a jumper caused by static can be enough to ignite them if they're suspended in the air. And this is still a problem. In 2008, an explosion occurred in a sugar refinery in Georgia, and there was another in 2010 in a flour mill in Illinois because of these substances suspended in the air, catching fire and burning. Now, I'm going to cause a little fire of my own to show you just how flammable these substances are. Hopefully, it won't be quite as dramatic as the Great Fire of London and I won't burn down all of Cambridge. The first thing I have to do is light by blowtorch. I've got my blowtorch. We've got a nice flame coming out of the top. Now what I've got here is a rubber tube and on the end of it is a little kind of container. What I'm going to do is put some corn flour in that container and then I'm going to blow down the tube. And that's going to cause a cloud of corn flour to go into the air. I'm going to direct that under where the flame is and we're going to see whether it combusts. So, I've put a teaspoon of corn flour in my container and I'm going to blow down the pipe. Do you want to count me down?

Audience - Okay, ready? 3, 2, 1...

Ginny - So, when I blew that cloud of corn flour into the air, you've got what looks like a kind of fireball coming out of the top of the blowtorch. You've got this big kind of ball of flame and that just shows, there wasn't actually that much fuel in that. It was only a teaspoon or two of corn flour. But because it's so well mixed with the air, it catches fire really, really easily and that's the same thing that can happen in bakeries and factories, working with these kind of powdered substances. And that's why they have to be really, really careful.

Comments

Add a comment