Have you ever wondered why some people enjoy being absolutely petrified by horror films? This week, The Naked Scientists investigate the spooky science of the genre: what does fear look like in the brain, how do you compose the most terrifying soundtrack and can we use psychology to engineer the perfect scare?

In this episode

Horror films 101

with Dr Simon Brown, Kingston University

According to Movieweb.com, there are over 250 horror films coming out this year. Including smaller independent movies - that number could be as high as 1000. And while horror films often get critically panned, their popularity is enduring. So when did our hunkering for horror begin? Georgia Mills spoke to Simon Brown, associate professor of film, TV and media at Kingston University about the genre...

Simon - I think human beings have been telling cautionary tales, campfire stories, folkloric tales for hundreds, possibly even thousands of years.

Georgia - That's Simon Brown - he's associate professor of film, tv and media at Kingston University, and the author of Screening Stephen King. We got together for a chat about the genre.

Simon - It's a broad catch or category and because genres evolve over time, because they're different. You know the type of horror films that may be emerging in cinemas now are dealing with different types of iconography, different types of themes than ones that may have been emerging in the genre in the early nineteen eighties. Because, fundamentally, what the horror genre is asking us to consider the things that frighten us, and the things that frighten us change.

Georgia - So what are the different types of horror film?

Simon - There are lots and lots of different types of horror films and they are aligned with, but not exclusively, different ways of trying to scare the audience. So, if you look at an early vampire film called "Vampyre" everything about that film is uncanny and strange and surreal. It draws on surrealism so everything is off kilter, everything is strange, everything is a little bit weird, everything is not the way it should be. So you have shadows that move independently of the characters. That's one way of doing it - that's surrealism, that's doing everything off balance.

At the other extreme you can simply go for the gross out. You can have films that are excessively violent, excessively gory. And that image of abjection, that image of the body in disarray, that image of bodies being dismembered, and the crunching noises of limbs being hacked off or whatever it may be, is another tool in the armory of the horror film maker.

And there are many, many things in between. There's suggestion - one of the finest horror films ever made is "The Haunting" which was directed by Rod Weissman, I think 1962, here, fundamentally, nothing happens. They're in a room and they hearing banging and the banging gets louder and louder, and you never know what's making the banging, but it's the not knowing that makes it scary.

A horror film is a genre in which you have almost unlimited freedom to do all manner of different things in order to get the reaction you want out of the audience. So there's gore, there's suspense, there's surrealism, there's the uncanny, and that's just a few of the things that you could use.

Georgia - BOO! Let's not forget jump scares!

06:14 - How does fear work in the brain?

How does fear work in the brain?

with Annemieke Apergis-Schoute, University of Cambridge

Horror films work by scaring us - but how does fear work in our brain, and how do  we learn which things to be scared of? Annemieke Apergis-Schoute gave Georgia Mills a shocking demonstration.

we learn which things to be scared of? Annemieke Apergis-Schoute gave Georgia Mills a shocking demonstration.

Annemieke - So fear is a very essential emotion. It's thought to be one of the oldest emotions, as for any kind of organism it's important to be able to avoid threatening situations. So you have to know when you're in danger and then to avoid these areas or stimuli of danger.

Georgia - We've all been there. There's something in the corner of your eye. A door creaks... there's a shadow in the corridor. You start to feel scared, your heart rate increases, you start sweating, your muscles contract. This is what's known as the fight or flight response. Your brain has decided you're in trouble, sends out kind of an alarm call. And hormones like adrenalin flood your system gearing you up to get the heck out of there... Turns out it was only the wind... big sigh of relief. But how do we learn which things we should be afraid of in the first place ideally so we don't jump out of our skin every time the wind blows.

Annemieke - What happens in the brain when you're learning about something new that's perhaps threatening, and you feel afraid because this stimulus is being paired with something aversive, we know that in the amygdala, which is a small almond shaped structure in the middle of the brain both of these stimuli come together. So all of your senses that take in what's happening in the environment, that gets transferred through sensory areas to the amygdala, and then also the input about the stimulus that it is of threat also gets into the amygdala. So, for example, if I was pairing a shock with a neutral stimulus, then something happens that's called associative learning and we know that this binding occurs in the amygdala, so the amygdala is central to learning about threat and, essentially, feeling fear in consequence for a certain stimulus.

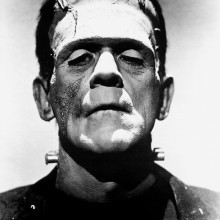

Georgia - Annemieke has a test she uses in her research, that lets you see your amygdala in action - it pairs a random stimulus - in this case a photo of an angry, green man, with an unpleasant result - in this case - a small electric shock.

Annemieke - Here you'll see two angry faces, and one of them might be followed by a shock while the other one is safe. And it would be up to you to figure out what's going on just by looking at the screen and then feeling when you get a shock and, at the same time, we record your skin conductance responses so we can see when you think you might be getting a shock. Because what will happen is your body will start to prepare for this shock and you will have little increases in skin conductance that we can see right here on the screen.

Georgia - Okay. So in response to being electrocuted by this machine, my amygdala will help me associate on of these scary faces with a nasty outcome and start to provide a fearful response which, I assume, is the sweating.

Annemieke - Exactly, yes. That's what you will be able to see.

Georgia - Well, I'm already nervous so let's give this a go. So I've got two sort of sticky pads with wires coming out of them on two of my fingers on my left hand.

Annemieke - Are you ready?

Georgia - Yeah.

Annemieke - Did you get a shock?

Georgia - No, I didn't get a shock from that angry green face.

Ohh yeah, it's gone off the charts there.

A red face now - no shock so far.

Oh no a green face.

Annemieke - It went up in preparation even though you didn't get a shock.

Georgia - I didn't get a shock. Ah, I see. So seeing that face...

Annemieke - So now what we can see in terms of fear learning is that every time you see the green face, we'll see a bigger increase in skin conductance than when you see the red face because you're starting to prepare for a possible shock. So after a couple of trials you will have figured this out and you'll see your skin conductance go up to it.

Georgia - Only one shock needed then before the mere sight of a green face instilled me with fear and my brain kindly got me ready to run away... not bad. But I also found that fearing something can actually help you cope with it because I stopped paying attention to the computer.

Annemieke - Fearing learning is almost instant. It was not even necessary to have a lot of these experiences and...

Georgia - Ahhh!!

Annemieke - I'll turn this off for you.

Georgia - Okay, thank you.

Annemieke - I think actually that you got an extra response because you weren't paying attention to it for a moment and then out of the corner of your eye you saw it again and right away got a shock. So it also shows you how being prepared can actually help a bit.

Georgia - Okay. Like you said - back to the evolutionary basis of fear - being able to predict when something is happening helps you a) avoid it and b) cope.

Annemieke - Yes, exactly. It is a good system. It's just that it can go out of order.

As you can see today, many politicians try to hijack this system as well by playing into our system of fear, and how we can so easily be manipulated to be afraid of things.

Georgia - Is there any evidence that what tends to frighten us changes as we age?

Annemieke - I think we habituate to a lot in the environment so, if anything, unless you develop an anxiety disorder, overall I think you'll become less and less afraid of stimuli in the environment. You just become more habituated to all kinds of things that can happen that are, in the end, not threatening.

Georgia - I mean I have a very strong memory of being in the cinema - I think I was about seven - and I was watching Disney's Hercules. Not meant to be a scary film but I was terrified and ran out of the room when there was a monster.

Annemieke - Yes. I think that children, they also don't have this area of the brain called the prefrontal cortex yet which is involved in downregulating a lot of these responses. So also, when you're learning about something that it's no longer threatening, this area is very much involved in signalling that it has now become safe. And this area is not very developed in children, so it's very hard for them to learn when things are in fact okay, and things are not threatening, or to downregulate an emotional response. That's why I think they have, in general, all their emotions seem much stronger, not only the fear responses but also the happiness that comes out.

Georgia - When you go to the cinema and you see something a big scary, often when you get home at night you see it again and again, and when you're trying to get to sleep it's still there with you. What causes this sort of repetition of the spooky things you saw in the film.

Annemieke - What I think that happens, like I said before, you create a memory of this certain stimulus, or object, or scene that is threatening and because that's so active at that moment in your brain you're still processing it. A process called generalisation starts to happen, so if you've just been around loads of snakes, for example, and quite threatening ones, and then you go for a walk in the dark in the woods. And normally you might have a response to that as well, if you see the stick on the road and you might jump. But in that case you're primed, essentially, so your brain system that's involved in detecting things in the outside world, so a sort of a saliency network, is much more active I think at that moment to detect similar stimuli in the environment. So then I think you get some generalisation where you see things that look kind of like it and you system is already prepared to respond to it.

Georgia - And I suppose, that again, that is another result of evolutionarily it being handy for you to spot something that scared you recently?

Annemieke - Exactly, exactly.

Georgia - So next time you're being haunted by witches and ghouls after seeing a scary film remember, it's just generalisation. And it probably helped you ancestors from being munched on.

15:06 - What makes films frightening?

What makes films frightening?

with Dr Simon Brown, Kingston University & Dr Hank Davis, University of Guelph

Horror films work best when they terrify us, but how do they tap into our fears? Georgia Mills got two different perspectives, first from Simon Brown, associate professor of film at Kingston University, who took her back through B-movie history...

Georgia Mills got two different perspectives, first from Simon Brown, associate professor of film at Kingston University, who took her back through B-movie history...

Simon - You can almost chart the things that we're afraid of by looking at the ebb and flow of themes as they emerge and disappear in the horror genre in cinema particularly, I would argue, in mainstream horror cinema.

Georgia - Okay so let's take a trip through the history of horror.

Simon - In the 1950s, it was all about - and these are connected to science fiction - it was all about the atomic bomb, and science gone mad. At the end of the Second World War we created something that could destroy an awful lot of people very, very quickly and ruin the Earth, and throw radiation into the atmosphere. So what were people afraid of in the 1950s? They were afraid of the atomic bomb.

Georgia - Let's take a look at the 50s - we had Godzilla, attack of the fifty foot woman, the blob - lots of creature features and mutants roaming on the big screens. Perhaps representing our fear of the atomic bomb. So what's next?

Simon - The big horror films of the 70s are The Exorcist, The Omen and probably Carrie. There are more but let's go with those for now.

What you've got there is a fear of young people. So Reagan in The Exorcist becomes possessed by the devil, Carrie has telekinetic powers, and Damien in The Omen is the devil himself, or the anti-Christ.

That reflects cultural and generational conflict in America in the late 60s and early 70s. You've got the older generation at odds with the younger generation who have gone through the summer of love. You know the older generation are looking at the younger generation thinking "oh my God, what are you guys doing?" And that gets depicted in these kind of classic movies from the 70s.

Once you get into the 1980s and the 1990s, again things start to shift a little bit. What are we afraid of in the 1980s and the 1990s? Paranoia - we're afraid of the government. So that begins to come out in films - the idea of people being taken against their will. Taken off to somewhere and tortured - that becomes a theme.

Then in the 2000s, in the post-9/11 era, you have the fear of terrorism, of the person next door, of leaving your house and being killed. So what happens is this gets reflected into sort of home invasion narratives - ghosts and spooks and spectres.

So I think that's how it works and I think if you go back and look at all the way through the 60s, the 70, I think you can really see these patterns emerging, and it's quite a fascinating thing to do.

Georgia - The horror genre seems to provide a reflection on our society's fears of the time - but films from the 60s can still scare us today, and as Simon pointed out - not all films fit this trend, so is there something else going on?

Hank - Hi, My name is Hank Davis, I am a Professor of Psychology at the University of Guelph in Ontario, Canada.

Georgia - Hank is the author of the book, Caveman Logic, and he approaches horror films from an evolutionary perspective...

Hank - Adaptations that our ancestors made way back in the Pleistocene era, that means maybe a hundred thousand years ago, are still with us, they don't go away. And some of those adaptations that we bring into the modern world are good, they're helpful and some of them are not so good. They were a lot more attuned to the Pleistocene era, yet we're dragging them around with us in the modern era.

Horror films certainly trade on those caveman adaptations that we carry around with us, and what makes a successful horror film, and you have to understand when we talk about success, we're talking about a billion dollar industry. So people are pretty strongly motivated to make good horror films, to get them right.

And from the point of view of caveman logic and from the point of view of evolutionary psychology, horror films are successful because they trigger one or more of three circuits. Three cognitive circuits that we carry around with us.

And the first I'd call predation. When you look back at the Pleistocene, we humans, or the early form of Homo sapiens, we were both a predator and a prey species. We try to hunt things down and eat them for our dinner and other things try to hunt us down. The phrase that I always loved is they were antagonistic food sources who were not quite ready to be eaten. But we ourselves were not quite ready to be eaten and were very sensitive to things that prey on us, to a sense of being stalked, to a sense of menace. So movies like "Jaws" or "Alien", or "Aliens" the follow-up, those play on our sense of being a prey species.

The second circuit that we carry around with us that makes for good horror films is what I would call "contagion" or "disgust." We are very, very aware of rotting bodies, gore, things. And it's very good that we avoid these things because they do harbour nasty bacteria that can kill us. So rotting organic matter is not something you want to play with or eat and we are so sensitive to any signs of it whether visual or, of course, olfactory - you know it stinks, we avoid it. And movies that make a big deal of showing us these kind of things are very triggery for us - they make us go - yuk! So movies like "Night of the Living Dead," where a zombie walks around with a loop of intestine in his mouth that he's munching on that he's just pulled out of somebody. Or "The Exorcist" where sweet little Linda Blair does this projectile vomiting of green stuff - yuk! - powerful image, good horror film.

The third circuit that we carry around with us that's very, very triggery which is what I would call "a violation of a sense of person." What a person is, what we can assume about something that we consider a person so, for example, a body with no soul. This is a powerful triggery thing for us. The biggest reason is that you can't reason with it. More than any other species on the planet, ours uses reason. We reason with each other, we are a very, very social species. So if we see somebody stalking us and we want to say "please don't kill me, don't eat me" we can have an interaction with it under normal conditions.

But if it's a zombie, and zombies are a great combination of all three of these triggers. If it's a zombie, the zombie just looks at you with dead eyes. It doesn't want to discuss it's hunger with you, it will simply eat you if it wants to. You can't negotiate with it. Zombies are also good because they're predators, they carry deep contagion. They themselves are dead bodies so you don't want to get too close to them. And finally, they won't reason with us.

Georgia - As well as ticking all three of Hank's boxes - zombie movies have been on the up - in the '90s there were 69 of them, but in the 2000s, this shot up to 255, so are they representing a cultural fear as well? Back to Simon...

Simon - In the more contemporary situation is that partly the zombie is about fear of disease and infection. When you think about the number of scares that we've had over the last ten years - H1N1, Bird flu, swine flu. This fear of disease, this fear of catching disease and this becomes very much reflected in zombie, this idea of the zombie is contagion. When you get bitten by a zombie you become a zombie. So I think really that's the kind of cultural fear that zombies are reflecting at the current time.

Why do we enjoy horror?

with Dr Hank Davis, University of Guelph, Dr Annemieke Apergis-Schoute, University of Cambridge

Whether it's a cultural fear, or something our evolutionary history has taught us to avoid - why do so many people enjoy being scared? Hank Davis is author of the book Caveman Logic, and Professor of Psychology at the University of Guelph, and he explained to Georgia Mills...

to avoid - why do so many people enjoy being scared? Hank Davis is author of the book Caveman Logic, and Professor of Psychology at the University of Guelph, and he explained to Georgia Mills...

Hank - In general, we seek stimulation, whether it's horror movies, or bungy jumping, or roller coasters, we simply seek stimulation.

Going to see a horror film is very much like jumping in the water but keeping one hand on the dock. We're safe. We know we're safe and we're going to expose ourselves to some amount of danger. But we also know at any point we can open our eyes and look around us and see the exit signs, see perhaps a friend or a loved one sitting next to us, so it's a very safe way to indulge in this kind of stimulation. Feel some of it's power but also get out quickly if we need to.

And, of course, there are huge individual differences in that. You couldn't get me on a roller coaster and you perhaps would spend an entire afternoon on them. So there are individual differences.

Georgia - So don't worry if you're not a horror buff - we're all a little bit different. But why would taking your fear circuits for a test drive give you a buzz? I asked Annemieke Apergis-Schoute what's going on in the brain.

Annemieke - All of these systems that are also involved in fight or flight modes also activate your system to be more aroused and to be in this state it also has overlap with other states of more positive types of arousal. So, in essence, to have a bit of this extra adrenalin running through your system can also afterwards make you feel nice, especially if you then realise that you're not actually in danger.

26:49 - The sound of fear

The sound of fear

with Professor Dan Blumstein, University of California, Los Angeles

One of the things people do when a film is getting too spook, is turn down the  volume. Sound is a really big character in horror films, but what makes a sound scary? Dan Blumstein is a professor at the University of California, Los Angeles, and he explained to Georgia Mills why small ground squirrels might hold the answer...

volume. Sound is a really big character in horror films, but what makes a sound scary? Dan Blumstein is a professor at the University of California, Los Angeles, and he explained to Georgia Mills why small ground squirrels might hold the answer...

Dan - I study marmots which are big ground squirrels, and I run a long term study of marmots that have been studies in Colorado since 1962. And for this study we catch marmots, and we mark them, and we release them, and we study them throughout their lives. So I know marmots pretty well and I'm enthused by marmots.

I'm casually handling a baby marmot one day and we put marks on them. I'm holding it gently and it starts screaming and I almost dropped it and I wondered why I had that feeling - why did I have an emotional response to a marmot screaming in my hand? I'd never had one scream in my hand before. I hear them alarm call all the time - I don't have emotional responses there. And that got me asking what's going on with this scream, what's going on with this sound?

Georgia - Ladies and gentlemen, the marmot scream:

Eeek eeek

Georgia - How did you make them scream?

Dan - well we weren't making them scream, we were just gently holding them and pulling hair from their back to get DNA and putting marks on their back so we could tell who they were. And every once in awhile they would scream and we'd say oh no, not again.

Georgia - Thankfully no squeezing of marmots then, but why did this sound have such a pronounced effect?

Dan - So I'm reading around, and looking and listening to screams and it turns out that Darwin didn't know what marmots were - nowhere in Darwin is the word marmot. But Darwin knew what screams where. Darwin said "that screams where cries from young to assist help from their parents." And I said "okay that's interesting" - all these species scream. And I listened to this hunting tapes which are horrible things that hunters use a lures to lure in predators usually to kill then or trap them and, if you look at the structure of these screams, they're all the same. If you listen to humans scream, they're very similar as well.

Screams are produced when animals overblow their vocal production systems - what's that mean? Screams are produced when a system becomes over-stimulated and works outside its tolerance. So if you turn up your stereo it sounds good, it sounds good as it gets louder, you're rocking along and then suddenly it's way too loud and the sound becomes sort of predictably unpredictable. It becomes noisy, as rapid frequency shifts it just sounds bad. Well that system is no longer acting in a linear way. And there's a series of these acoustic attributes that are associated with overblowing a system, and none of them is noise. Specifically, it's deterministic chaos but it sounds like noise. It sounds raspy, it sounds rough. And these things are found in all animal screams and human screams as well.

So it seems like there's something because of how screams are produced. There's something common among many species that makes screams particularly evocative that we listen to other species vocalisation and maybe have an emotional response.

I'm giving a popular talk about this in LA. There are no marmots in LA but there are a lot of people who make music and film soundtracks and I said "I bet this works for a movie soundtracks. I bet musicians do this to influence emotions." And one guy comes up later and says "yeah you know I'm a film score composer and I study how emotions in music are communicated. And I said "oh that's interesting" and he goes "I bet you're right." and I go do you want to collaborate," and he's like "yeah."

So we ended up getting an honour student to work with us and the three of us sat down together and we're listening to a bunch of these sounds. We're looking at movie soundtracks and we're getting the best movies, the best horror movies, the best adventure movies, sad, dramatic movies. And we had a series of predictions. We said that these nonlinearities are really emotionally evocative at a fundamental level, then we should expect more of them in really scary scenes and really scary movies, and fewer of them in sad, dramatic films, and things like that.

We scored them and we found something really interesting, we found that these nonlinear acoustic attributes - this noisy type stuff - was over-represented in climatic scenes in horror films, and was under-represented in sad, dramatic films. Suggesting, in a correlative way, well yeah the noise and these nonlinearities are emotionally evocative and they're used specifically to get people's attention and make them aroused.

Georgia - Next, Dan wanted to see how this noise impacted our emotions. He teamed up with composer Greg Bryant, they made marmot inspired music to go along film clips- little ditties either with or without this 'noise.'

Dan - And what we found was that there were emotional responses to these sounds, specifically the noise and abrupt frequency shifts whereby people felt more negative and more aroused when they heard these things.

So basically, the story is by listening to my inner marmot, I discovered that there's a way to understand why we're scared, what's arousing, what's fearful. And what's fearful are these nonlinear type sounds that are produced honestly when animals are really scared and we listen to these and respond to these because our ancestors listened to these and responded to these. And we listen to these and respond to these because they're normally associated with bad situations. When animals are normally screaming they're being killed or in serious dire straights and they're sort of unbluffable, honest, messages that you should pay attention to what's going on and be scared.

Georgia - So what about it is unbluffable?

Dan - When animals are really scared, if they sort of overblow their system they're reliably producing these sorts of sounds. And if they're reliably producing these sorts of sounds only in situation when they're really scared and overblowing their vocal production system, that becomes a very honest signal. There's no reason to necessarily have that if you're not scared, but it might be an inadvertent honest signal that's associated with being scared or a cue that others can cue in to and can associate the producer of that sound as being in a bad situation.

34:06 - From Jaws to Psycho: spooky soundtracks

From Jaws to Psycho: spooky soundtracks

with Janet K Halfyard, Birmingham Conservatoire, Birmingham City University

What makes soundtracks sound scary, and what musical notes can creep us out most effectively? Janet K Halfyard, teaches courses on film music at Birmingham Conservatoire, and she gave Georgia Mills her top tips on making terrifying tunes...

Janet - I do an experiment with my students where I play them the same piece of film with different music. And music has a really profound ability to change the way we believe things are happening. So with this particular clip, it's a man and woman and in one version of the film with romantic music 'he's in love with her.' In the version, where I take some music from a horror film they always say 'he wants to kill her.' And it's the same clip of film so music has the ability to interpret the image for us; to anchor it into a particular meaning.

Georgia - Why do you think it has this effect?

Janet - Music works on us in a very profoundly psychological way. There are certain things we know about the world we live in from how we hear it. For example, horror film music uses extremes of sound so it will use very high sounds, it will use very low sounds, it will use very slow ones and extremely fast ones. And part of this is because of the way that this sound registers with what we know about what those sounds mean in the real world.

So, for example, with those really low sounds that you'll find in things like Danny Elfman's main title for Sleepy Hollow, which uses a great, deep kind of Russian choir voices and church organ. You have these very low sounds which tell us there is something enormous there because the bigger something is, the lower the sound it makes. And so having this idea of the enormous thing that you can't see, you can only hear. That's one aspect of how music becomes frightening.

Jaws is actually a prime example. You have those very, very deep string sounds - duh, duh, duh duh - and then it starts running towards you - duh duh, duh duh duh duh. So it absolutely is, you've got this huge thing that is lurking and then starts to run towards you and that's extremely frightening.

So one of the most effective horror music ever written. With the high pitch sounds, it's kind of like someone's screaming. Particularly because the high pitched sounds will quite often be discordant. They'll be clashing and jarring sound high up. And so you've got the Psycho stab cord from the shower scene going eek, eek, eek. It's these kind of shrieking, jarring sounds that tell us, again, somebody's screaming. That's the kind of the underlay of what's happening there.

So there are these particular types of sounds, therefore, that say "this is frightening" to us.

Georgia - Are there any particular notes or chords that are just more scary?

Janet - Yeah. I mean, if you have two notes which are really close together in pitch and you play them together, they will kind of interfere with each other. They've got a set of frequencies purely, again, at the physical level, those frequencies will clash and beat against each other, and that's part of what will create that shrieking effect particularly when you have two notes played together very high up, they will really jarr against each other. And it's unnerving, it says again "this is wrong." So I think that's one of the big messages that horror music gives us is that things are going wrong.

I have to say, one of the biggest horror gestures is the use of silence - of actually having no music at all because then you've got no information.

Georgia - Firstly, that's a much easier job for the composer, I suppose?

Janet - Much, much easier for the composer. But they can exploit it by having the music and then the music will suddenly stop for a very brief moment and then "wham", it kind of hits you with the scary stinger that makes you jump out of your skin.

Georgia - I suppose in nature we're used to it being noisy - bird song and things like that and when it stops I guess something's gone wrong?

Janet - Something's coming, yes. I think a lot of the way that music in horror films works is to play on the way that we expect sound to work in the real world and yes, silence is really unnerving.

Georgia - So we've got silence, deep low sounds, and high clashing notes which can all make music more creepy. But apparently there's one interval, and that's the difference between two pitches, that has been used to scare us for over a thousand years.

Janet - Possibly the most important interval in horror music if there is a single musical sound which is something called a tritone - dum bah is how is sounds - doo doo. And in the medieval period they called this the "diabolus in musica" - the devil in music. Because it was the most discordant interval that they knew of and it seemed, therefore, it was the disruptive thing - the devil in music. And composers have been using the tritone forever, in terms of evoking evil. You find in the The Simpsons theme as well...

Georgia - That well known horror!

Janet - Absolutely, but it's there to be disruptive, it's there to be discordant. It's like this constant wrong note. It's what makes The Simpsons theme so quirky. If you put it into a different context and it actually becomes scary - it sounds so wrong, so discordant that a lot of composers have written music that puts tritones in. It's like a weird angle, it disconcerts us and we don't necessarily know why, but we know that it's wrong.

41:21 - Creepy compositions!

Creepy compositions!

with Antony Bagott, Composer

Can we use the science of spooky to make a chilling composition? Georgia Mills  teamed up with composer Antony Bagott to try and make the world's scariest theme.

teamed up with composer Antony Bagott to try and make the world's scariest theme.

Antony - Hi, my name's Antony and I'm a composer.

Georgia - Antony's scored film music in the past and he's also done a piece for us. You might have heard...

[NS theme tune]

Georgia - I got Antony on board to see if we could use the science of fear to compose the world's most scary soundtrack...

Antony - Huh huh yes, that's exactly what we were doing.

Georgia - I dropped by his composing studio, which turned out be a laptop with some nifty software installed.

Antony - And that just helps me get all the tracks together so you can choose lots of different instruments and mix them together on different tracks.

Georgia - Okay, so we can have all the instruments we want, but the only one I can actually see here is a keyboard.

Antony - Exactly, yes. So everything that goes through the keyboard can be outputted as any sort of sound that you want.

Georgia - So right, how do we start?

Antony - I think we should probably start with some sort of low bassy note. So let me see if I can find one of them.

Georgia - So this would be representing the sort of big unseen menace?

Antony - Exactly, yes! If I do a really low note on this instrument it does this sound...

Georgia - Oh - like an insect.

Antony - Like an insect, exactly yeah.

Georgia - You should use that definitely.

Antony - Yes, definitely. So we could mix those two base notes together. We could have that one as a sort of base tone or drone type thing and have the insect coming in now and then.

Georgia - So we're actually getting a plot to our film as well.

Antony - Yeah exactly. Maybe this could be some sort of killer insects or something.

Georgia - So we've got a plot to our movie soundtrack - I'm sure most film makers come up with the plot before the soundtrack, but hey. So next we need some of those high clashing notes Janet was talking about.

Antony - Perhaps we could have something like - if we use violins which are used, obviously, in quite a few film soundtracks and film scores. We can get something like this...

Georgia - Am I going to get sued for copyright?

Antony - Yes, maybe. So obviously that's a well known sound. That's just using the tritone.

Georgia - Ah, the devil in the music?

Antony - Exactly, that's the one. That was staccato violins, so we could also do something like... And one thing we can also do with that, there's a sort of pitch-bend pedal here that I can use to make it go...

Antony - high sounds we can have a pizzicato violin which is quite often used to give a creepy another sort of insecty sort of feeling, a feel...

Antony - like that

Georgia - Oh, I like it.

Antony - So that can also go in the background and you can have it going low to high... to sort of build tension.

Georgia - That's the insect creeping up the wall.

Antony - Yeah, exactly. You can also have a few more electronic instruments... those sort of strange sounds.

Georgia - So that's quite noisy?

Antony - Yeah. Noise, obviously, is a good way of making people feel uneasy because it doesn't sound nice, basically. Filling the score with noise is a good way of making a person feel on the edge of their seat.

The science of suspense

with Dr Keith Bound, Receptive Cinema

Could brain scanning technology help us to peek inside the audience's mind and  tell us exactly what to do to light up their fear centres? The term neurocinematics appeared in 2008 and suddenly this was the new frontier of cinema. This technology is already used in Hollywood to help pick the most effective trailers, so why not movies? Well, the hubbub has since died down, but Dr Keith Bound, at receptive cinema, has been doing something similar, as he explained to Georgia Mills...

tell us exactly what to do to light up their fear centres? The term neurocinematics appeared in 2008 and suddenly this was the new frontier of cinema. This technology is already used in Hollywood to help pick the most effective trailers, so why not movies? Well, the hubbub has since died down, but Dr Keith Bound, at receptive cinema, has been doing something similar, as he explained to Georgia Mills...

Georgia - But maybe science can help give us the creeps? There was a study back in 2008, where scientists at New York University put people into MRI scanners, which can measure your brain activity. They got people to watch clips of Hitchcock production "Bang! You're dead", the western "The Good, the Bad the Ugly", and the comedy "Curb Your Enthusiasm". They found that when watching Hitchcock's work, in 65% of people their brains tended to respond in a really similar way, this was much less so for the western, and only 18% of people responded the same way to "Curb Your Enthusiasm".

It seems Hitchcock was very adept at pulling our strings, but could this same brain scanning technology help us to peek inside the audience's mind and work out exactly what to do to light up our fear centres? The study coined the term neurocinematics and suddenly this was going to be the new frontier of cinema. This technology is already used in Hollywood to help pick out the most effective trailers, so why not movies? Well, the hubbub has since died down a bit; in fact the website of one of the major proponents of this idea now sells bouncy castles. So perhaps not this massive cinematic revolution, but Dr Keith Bound, at Receptive Cinema, has been using his own technique to do something very similar...

Keith - Basically, what I'm doing with Receptive Cinema is really acting as a film consultancy. So the film consultancy is based on my research and it's really about implementing that research findings in a creative way, so bring in science of suspense, in particular in horror films, and help in that sort of data and information work more effectively so that we can create films that are more scary or more suspenseful in that sense.

Georgia - According to Susan Smith, who looked at Hitchcock's work, there are three types of suspense:

One - you, the audience, are in on it, you can see the big bad, but the character in the film has no idea. It's behind you! This is called vicarious suspense.

Two - the audience and the character are both in on it, this is called shared suspense.

And finally - there's direct suspense, which is where you're worried about something on your own, and not any character's, behalf. For example, the camera tracks through a dark forest and you are scared a face might pop out at you at any moment.

So which works better? Keith showed people short 90 second clips from films like Quarantine, the Descent and Silent House. And then to find out how anxious people were in real time, he measured their sweat using the same technique Annemieke used on me, earlier.

Keith - Basically, if you imagine these responses like little mountain peaks in a signal. So we actually get one curve that comes up as an amplitude so we know that the higher this curve goes the more intense that person's feeling that experience. And the longer it goes on, in other words until it reaches a peak, that's the durability. So I measured anxiety by durability - how long the person was experiencing that anxiety response, and also the intensity and that's based on the height of the actual curve.

Georgia - Keith's technique can tell us things that we might not pick up on our own...

Keith - Consciously, we would not know which part of a film clip makes us most scared, certainly by the millisecond. We might know a certain section that made us feel very tense but with this psychophysiological recording we can measure it by the millisecond. Now we actually can understand - this is exactly this stimulus you've got here when the lighting changed, the camera moved, or there may be some other factors that we can actually find, this is when you've experienced a very intense form of suspense or anxiety in this case.

So what the psychophysiology does is really pinpoint where we are experiencing this very strong or weaker anxiety response.

Georgia - Keith discovered that vicarious suspense, that's the one where you the viewer, but not the character, can see the danger, elicited the most strong reaction from viewers. This makes sense because this was Hitchcock's favourite form of tension.

But also, contrary to what you might expect, people's anxiety in a scene actually dropped once you could see the threat, especially when jump cuts were used. What people really responded to was a close up of the petrified face of the victim. So now Keith can use these and more findings to advise filmmakers exactly how to elicit the best response from people. But surely... everyone is different?

Keith - You won't have an exact formula for everyone - I have to make that quite clear. Everyone has a different preference, but what I did find is that you can get, in the clips like Quarantine I mentioned earlier, the vicarian, a very strong one. That did have a very consistent, very strong intense anxiety responses, but there weren't many of them. You don't get hundreds of these things happening in the clip. But at the same time you will get other ones that will have a weaker response to the same stimulus because, remember, people bring a lot of things from their past into the cinema.

Basically, when you go and see a horror film you're going to create a mood that you're going to get frightened or scared or you're going to put yourself in a mood of what you want to be when you watch that film. That mood then, what happens is that your brain will start picking out any element in that film to support that mood, so your fear's likely to intensify. But, like you said, it does depend on certain elements and not everyone will have exactly the same result. They may have an anxiety response, but some will have a stronger and some may have weaker.

Georgia - Dr Keith Bound from Receptive Cinema. So maybe science will be able to make our films more scary in the future, but to be honest - they're doing a fairly good job of scaring the pants off of us already.

So next time you're watching a horror and in dire need of a sofa to hide behind, perhaps you can distract yourself by remembering - it's all in the amygdala, and now you know exactly how these directors are trying to scare you, and why it works. I'm off to the cine

Comments

Add a comment