Does smoking dope decrease your potential for pleasure? How the simple act of dieting can rewire brain and a blood test for depression. Reporting from the British Association for Psychopharmacology 2014 Forum.

In this episode

03:03 - Uncovering schizophrenia through skin

Uncovering schizophrenia through skin

with Kristen Brennand, New York Stem Cell Foundation

Hannah - In this episode, I'm reporting from the British Association of  Psychopharmacology 2014 Meeting in Cambridge. Does smoking dope decrease your potential for pleasure? Now, the stereotypical stoner is often portrayed as an unmotivated apathetic armchair philosopher. A new research reveals the biological underpinnings for this with chronic marijuana use, rewiring the brain, making it less sensitive to the motivation and reward chemical, dopamine.

Psychopharmacology 2014 Meeting in Cambridge. Does smoking dope decrease your potential for pleasure? Now, the stereotypical stoner is often portrayed as an unmotivated apathetic armchair philosopher. A new research reveals the biological underpinnings for this with chronic marijuana use, rewiring the brain, making it less sensitive to the motivation and reward chemical, dopamine.

Michael - And when people smoke lots and lots of Cannabis over time, the dopamine system can become used to being stimulated. And so, it tries to adapt.

Hannah - How the simple act of dieting can rewire the happy brain chemical serotonin, making you more compulsive and increasing your susceptibility to developing an eating disorder.

Philip - And without meaning to, if you lower brain serotonin levels through dieting, that can lead to lower mood and more compulsive behaviour. So, the dieting really gets a grip on you and it's very hard to stop.

Hannah - And depression in teenagers...

Lesley - Estimates vary, but probably around 5% to 6% of adolescents have moderate to severe depression.

Hannah - The shocking stats and what we can do to help lift their mood.

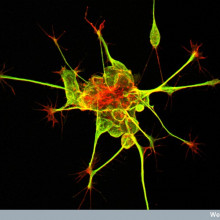

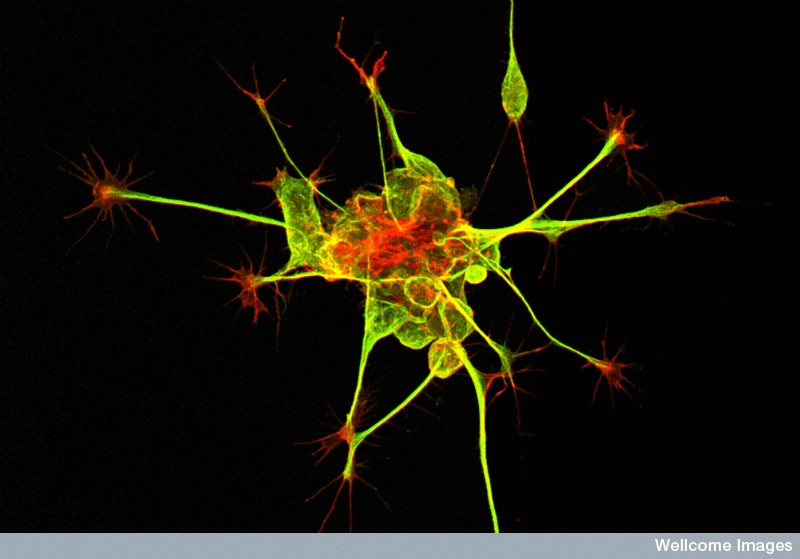

First up, the Naked Scientists Kate Lamble met Dr. Kristen Brennand from the New York Stem Cell Foundation. She's been punching into people's skin, and using clever chemistry. She converts the skin cells that she picks up into brain cells which she grows in a dish, all part of a quest to unravel the mysteries that surround the condition, schizophrenia...

Kristen - So, Schizophrenia is a really common and really debilitating disorder. It affects about 1% of people across the world in every culture and every country. And those who are affected, the common symptoms are hallucinations and delusions. There are of course many, many other symptoms but that is the classic phenotype.

Kate - What goes on in the brains of people with Schizophrenia? Do we know what causes these symptoms?

Kristen - So, that is actually a really complicated question. Actually, just this morning, a paper came out in a really famous journal Nature, showing that there are now 108 genes that have been implicated into Schizophrenia. So, we know at least 108 ways that somebody can be Schizophrenic and the answer is probably even more than that. It seems like the brains of patients on the whole are affected. In post mortem studies, we begin to see that the brains are smaller and in functional (fMRI) imaging studies of live patients, we can see their brains don't connect as well. But the short answer is no. we don't know all the ways that things are going wrong in the brain are people with Schizophrenia.

Kate - Why is it so important that we unpick this problem? Is it really important for treatment?

Kristen - Well, I think it's really important for treatment. First aside as a whole, as I said, any time 1% of the people. There's 100 million people around the world are affected by a disease. You really want to understand why and treat it. this is a really debilitating disease. 95% of patients who are diagnosed with Schizophrenia will never again will have a full time job. 50% will have drug and alcohol abuse problems and in the US at least, 1 in 5 will be homeless and live in the streets. So, this is a really important disease that has no cure that it would be wonderful if we could get insights in new medications to help these people.

Kate - So, you've been using stem cells to help unpick this problem. How have you gone about looking at that?

Kristen - In 2006, a remarkable discovery was made by a researcher in Japan by the name of Shinya Yamanaka. What he showed is that you could take skin samples from any person on the planet and reprogramme those into stem cells. Stem cells of course can become any cell type in the body or at least this type of stem cell can be. And so, what I've done is I've taken skin samples from healthy controls and from patients with Schizophrenia and turn them both into stem cells. And then those become brain cells - neurons - that I can compare. And so, we started by asking really basic questions - how are the brain cells different between patients with Schizophrenia and healthy controls? And we've begun to see a few differences. The second question is, why are they different? That's really the hard question. It's, why are these cells different and how can we make them the same.

Kate - When you take stem cell and you turn it into a neuron, is that a good model for neurons that are found in adult brains or are they slightly different?

Kristen - They're more than slightly different unfortunately. We have been doing gene expression comparisons of neurons from our stem cells and what I can tell you is when we compare them to neurons in human tissue, they're most similar to first trimester foetal tissue. So, our cells are really young. Nonetheless, they fire action potentials, they form synapses so the cells that we make from stem cells are functionally similar to the neurons in the human brain. But there are some really important limitations. They're not myelinated like those in the brain might be and they're heterogeneous. So, they're not all of one cell type. As a consequence, they wire in ways that they don't typically wire in the brain. So, it's a model. It's an imperfect model, but it's at least a source of live human neurons to study.

Kate - So, when you look at the differences between the neurons that you've created from controls and the neurons that you've created from those with Schizophrenia, what are the differences that you start to see?

Kristen - There are a few major types of differences that I and other groups have seen. Some of the commonalities that we see is the neurons don't connect to each other as well. So, they have fewer branches, fewer dendrites growing from the soma. They have fewer synapses along the dendrites and functionally, some groups unfortunately - not mine, but other really great groups have shown that the synapses are not as functional. They don't fire as often between the neurons. Collectively as a whole, I think the field has shown poor connectivity, reduced synaptic activity and structure, increased oxidative stress and aberrant migration of Schizophrenia in neurocells.

Kate - So, the cells from people with Schizophrenia were acting slightly differently, but there are these 108 gene that might play a role in that. Do we have any idea what's causing that?

Kristen - It's likely that in every patient, their cellular phenotypes might be coming from different mutations. In fact, I've genotyped my patients and they don't share the same mutations. So, it seems like collectively, pathways are being effective. They have the same downstream consequences but the genetic root is actually different in each patient.

Kate - So, does noticing these changes, does that help us to develop drugs which might solve them?

Kristen - So, that's actually the ultimate goal - is to have a drug screening platform. I can make a limitless number of neurons from any patient with any genetic background. And so, the hope would be that the geneticist can collectively sort patients into maybe 500 or a thousand different ways of having Schizophrenia and that we could then do a drug screen for each of the thousand different ways that one could be a Schizophrenia. And so that your doctor will ultimately might say, "You're type 208. You should use this drug and this dose." And so, that's I think the ultimate place that the stem cell originally wants to get to is drug screening.

Kate - So, this is sort of going into the personalised medicine idea. You'll know exactly what type you have of the hundreds and then they wish drugs will be able to help you.

Kristen - It's a very similar approach to what people are doing for cancer right now. Yes, the goal is to better predict what drug will help and to avoid the side effects from those that don't.

Hannah - Thanks to Kristen Brennand speaking with Kate Lamble.

08:47 - Cannabis rewires the brain

Cannabis rewires the brain

with Michael Bloomfield, Imperial College London

New research has shown that long-term marijuana use rewires the brain, making it less sensitive to a feel-good chemical called dopamine, and leaving users at risk of becoming depressed and demotivated and at risk of psychosis. Hannah Critchlow visited the British Association of Psychopharmacology 2014 meeting to speak with Michael Bloomfield, from Imperial College London...

Michael - We know that people who smoke lots and lots of Cannabis and particularly, during adolescence when they're teenagers and more at risk of having mental health problems later on in life.

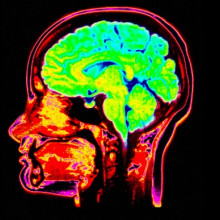

The one that we're particularly worried about is something called Schizophrenia. This is a potentially devastating mental illness where people can for example, hear frightening voices and become quite paranoid, become quite scared. It's very important to understand how that increase in risk from smoking Cannabis and Schizophrenia is happening. So, based on research using a brain scanning technique called Positron Emission Tomography affirm our group in London which is led by Dr. Oliver Howes. We know that people who have Schizophrenia have a tendency to make large amounts of the brain chemical dopamine. So, we wanted to find out if people who smoke lots of cannabis also have the same imbalance, so also had lots of dopamine to see if that could potentially explain how smoking lots of cannabis increases risk of Schizophrenia.

Hannah - I think it's estimated that something along the lines of 6% of the UK population aged between 16 and 24 will regularly smoke cannabis. What proportion of those will then go on to develop Schizophrenia? What's the risk? What's the link between cannabis and Schizophrenia?

Michael - There's some debate between scientists about how much it increases the risk. Most of studies tend to agree that it about roughly doubles the chance of getting Schizophrenia. I think the key thing that's really, really important is that the risk is most elevated at its highest for people who smoke cannabis very regularly, particularly during their teenage years. That's the time that it's most risky.

Hannah - Going back now to the PET scanning that you did looking at this dopamine chemical in the brain...

Michael - Dopamine is a really interesting chemical in the brain that does lots and lots of things. One of the things that it does is send a signal within your brain when something exciting potentially is about to happen, something rewarding. And so, it's involved in motivation. Now, we found within the cannabis users that there was a correlation so a relationship between their motivation levels and their dopamine levels. What we found was that the lower their dopamine levels were, the more unmotivated that they felt.

Hannah - So, your brain lights up with dopamine and reward when you're feeling things of pleasure and when you're getting keyed up to be motivated with something. Cannabis actually decreases the amount of dopamine that's in your brain. Is that right?

Michael - What we think is happening is that if you smoke cannabis that it probably releases a bit of dopamine. When people smoke lots and lots of cannabis over time, the same with recreational drugs that people can use, that the dopamine system can become used to being stimulated. And so, it tries to adapt. It tries to respond to this by probably lowering the amount of dopamine that it makes.

Hannah - How much cannabis would you have to smoke? I mean, from your studies, you're only looking at 19 smokers of cannabis. So, in comparing them against those that didn't smoke cannabis. So, you're only looking at 19 people, but how much cannabis do you have to smoke in order rewire and alter your dopamine, kind of rewards pathways in the brain?

Michael - In our study, all of the cannabis users were quite heavy cannabis users. So, most cannabis in the UK is sold as 1/8 which is an 8th of an ounce. That's roughly 3.5 grams. The cannabis users in our study was smoking an 8th. It would last them roughly half a week and most of them are smoking a quarter on an ounce of cannabis a week which is quite a lot. I think the other really interesting thing is, presently, we're understanding a bit more about the different chemicals in cannabis. So, there are probably almost 100 different chemicals in cannabis. Depending on the balance between these, that they probably have different effects on the brain. So, there's one called THC which is the main one and another one called CBD. What we think is really important is it's the balance between these as to the effects that they have on the brain in the short term, but also the long term.

Hannah - So, bottom line then in your studies at least, regular cannabis use - so, at least a few times a week - can actually decrease or desensitise your brain's reward pathways so that you might get feelings of apathy and lack of motivation. And that's what we also see with people that smoke cannabis regularly. You do stereotype them as kind of being quite lacking in motivation.

Michael - Certainly, that's what we believe based on the findings that we have. I think the story is beginning to fit together. Almost half of young people have tried cannabis at some points in their lives and I think that smoking lots of cannabis over a prolonged period of time does seem to have this effect. There is some work that's been done in the past that's looked at educational outcomes. It's found that people who smoke lots and lots of cannabis and importantly, carry on smoking lots of cannabis can affect how they do at school or a university or in their work life. this might tie into that quite well. I think the other thing as well is that there's some evidence that people who smoke lots of cannabis regularly are more likely to get depressed. This is a bit more controversial because it's very difficult to tease out if cannabis is making people depressed or if people who are depressed for example have low mood are more likely to smoke cannabis to try and feel better about it. but also, we know that this chemical dopamine is probably involved in depression as well. One of the key symptoms of depression is not being able to enjoy things. And that's if anything, the one that people find the most upsetting as they're not able to enjoy things that they used to enjoy. I think it may tie in with that as well, but I think again, we need to do more research into how all these things affect dopamine and that affects how we feel.

Hannah - So, those people who have smoked cannabis regularly and might feel that they changed or altered their dopamine reward pathways in their brain. If they stopped smoking now, would the brain rebalance itself and retweak itself so that they could feel feelings of joy and reward, and motivation later on.

Michael - Some of the studies that had been done have looked at people who used to smoke cannabis. In those studies, they've only found very, very small effects if any, on the dopamine system. So, what we think happens is that after a period of abstinence that the brain get back to normal again. And so, I think if people are worried about the amounts of cannabis that they're smoking, if it's having negative effects on them and my advice would be to either stop or at least cut down the amount of cannabis that they're smoking. If they need help with this then it's about time they see their general practitioner.

Hannah - And going back to patients with Schizophrenia or psychosis, so patients with Schizophrenia have increased amounts of dopamine and cannabis seems to decrease in the amount of dopamine that your brain is sensitive to. In that case, people with Schizophrenia or people that have a predisposition to Schizophrenia in some ways self-medicating with cannabis.

Michael - That's a really, really interesting question. I think that's certainly a possibility and we need to do quite a bit more work to tease out these really important points. In our study, all of the cannabis users, although they experienced a temporary increase in psychotic-like experiences - so these are strange experiences all of us can have in everyday life - none of them actually had Schizophrenia. So, I think a really good study would be to look at people who did have Schizophrenia and who wants to smoke cannabis.

16:17 - How to prevent teenage depression?

How to prevent teenage depression?

with Lesley Cousins, Cambridge University

Hannah - Next, teenage behaviour can have its ups and its downs. And it's not really  surprising, given all the brain changes that occur in the adolescent years, but at what point do the lows become clinical depression? With suicide the leading cause of teenage death after car accidents, how best to diagnose and treat depression in these years and can the teenage brain ever fully recover in adulthood? Kate Lamble met up with Dr. Lesley Cousins from Cambridge University to find out.

surprising, given all the brain changes that occur in the adolescent years, but at what point do the lows become clinical depression? With suicide the leading cause of teenage death after car accidents, how best to diagnose and treat depression in these years and can the teenage brain ever fully recover in adulthood? Kate Lamble met up with Dr. Lesley Cousins from Cambridge University to find out.

Lesley - Estimates vary, but probably around 5% to 6% of adolescents have moderate to severe depression. Interestingly, the incidents increases as you go through adolescence. So something is happening in your teenage years which seems to make you susceptible to the risk of becoming depressed.

Kate - And so, if a teenager says to his mum that they've got depression, what normally happens? Is there talking therapies or is there a drug response? What's the normal response?

Lesley - I think it depends and I think it depends how that young person presents. I think there's very few teenagers that stand up and say, "Mum, Dad, I think I'm depressed." And for moderate to severe depression, the treatments are talking therapies and anti-depressants.

Kate - So, these anti-depressant drugs, if we've given them to someone, a teenager with the developing brain, sort of there's something going on in their brain, have we tested those drugs on teenagers or are they tested on an adult audience?

Lesley - I think that's a really good point to make. There's two periods in your life where you have this rate of brain development when you're a baby toddler and then in your teenage years. So, your brain is changing markedly in this time. there's two answers to your question. One is, you're asking if you tested these medications on teenagers and yes, we have in this instant. We know that they are a relatively effective treatment for depression. For about 5% to 6%, they help. We don't really know what antidepressants are doing generally to adult brains or adolescent brains. A decade ago, there was some concerned raised that antidepressants might be associated with increase in suicidal thoughts in depressed teens. That led to a real drop in prescribing rates. Worryingly, what that then led to was an increase in suicide and suicidal attempts in young people. Although there was a possibility that there's a slight risk in treating young people, what we know is the biggest risk is not treating young people. Having a depressive episode in your teenage years is absolutely catastrophic. So, your teenage years are when you lay down the foundations for the rest of your life. that's where you achieve it. academically, that's where you learn how to develop and maintain relationships. So, if you have 6 months depressive illness when you're 15 and doing your GCSEs, that has an entirely different catastrophic consequences than if you have a depressive illness say, maybe for 6 months when you're 30.

Kate - So, how in particular are you looking at this problem?

Lesley - Really, I was asking the question of, do we, prescribers were supposed to. As clinicians, we get guidelines on how to prescribe antidepressants and these guidelines are laid down by NICE. The NICE guidelines for child and adolescent depression state that you shouldn't give antidepressants until somebody has had their talking therapy. So, until they've had a field course of talking therapy and then you should give antidepressants based on the severity of depression. So, the more symptoms you have, the more likely you should be prescribing. And really, my question was, is this what we're doing? The answer is, no, we're not. What we're doing is we're prescribing before people have talking therapy and I think I probably agree with that actually. talking therapy is very difficult to access. What the results that I'm presenting show is that instead of presenting for severity of depression for girls who present for risk, who present for risky behaviour, self-harm, and suicidality. And the worry with that is that we don't have an evidence base for that kind of prescribing.

Kate - I've heard from acquaintances who have been on antidepressants that they can make you feel in a very different way. They can make you feel sort of muggy or unable to access feelings. If we're prescribing those kind of drugs before talking therapies, could that affect the impact and the effectiveness of those talking therapies if they're met, having that sort of emotional reaction to them?

Lesley - It's a good question and it's probably fair to say that yeah, antidepressants do affect how you're thinking, how you act. But I think actually, evidence suggests the opposite from what you're suggesting. So actually, if you're really depressed, managing talking therapies is really difficult. Managing to discuss your feelings when you're depressed is hard. So actually, I think antidepressants can help people reach a level in their mood and their cognitive function that allow them to make the most talking therapies.

Kate - So, if you're concerned about this danger of the lack of evidence base when you're prescribing for girls based on risk factors, what's the danger there? What could we do? Are we prescribing too many or are we letting risky factors go by?

Lesley - I think the danger is we don't quite know what we're doing. So, psychiatrists working towards being a scientific and robust as it can be. And like I say, we have good evidence that antidepressants work in moderate and severe depression. These are the young people that's got to have the most impact. The grip of people who are risky, self-harming, I understand a clinician's need to act and feel the need to act, but we don't necessarily know that these treatments are going to be so effective in these young people if we're prescribing these in that rationale.

Kate - So, what's the next step with your research? Is it to get that evidence base for those girls with risky behaviour and whether those drugs are effective?

Lesley - All research just leads to more questions and the question for me is, what is it about girls that risk scares us but not depressive symptoms? Why are we treating boys and girls differently? Because we shouldn't be. Is it perhaps that as clinicians, we are used to seeing crying girls in our consultant rooms and we're possibly immune to that. it takes a sort of elevated level of action for us to pick up our prescribing pads whereas we're not so used to seeing crying boys and that's enough for us to prescribe.

Kate - So, you might be so used to girls in sessions when they're upset or showing depressive symptoms when they're crying that that doesn't act as an alert signal. But if a boy does that, that would act as - that's signal enough for you to get out prescription pad and give them something, a treatment.

Lesley - Possibly. Who knows? And I think what this highlights is the complexities that underlie prescribing and the agendas and preconceived ideas consciously and subconsciously that a condition has that they take into the consulting room that affects the conversations that they have and the decisions that they make.

Hannah - Lesley Cousins, presenting her work, showing that if you're a teenager with depression, whether or not you're prescribed antidepressants seems to be based on which county you live in and your gender rather than the severity of your symptoms, highlighting the requirements for more objective methods for diagnosing and helping to treat depression.

Well rather timely, in the news this week, the first blood test to help diagnose major depression in adults has been developed by Professor Eva Redei and her team at Northwestern University. Published in Translational Psychiatry, the test also predicts who will benefit from cognitive behavioural talking therapy. The study did look at just 32 depressive patients but if the results hold true in larger scale studies, there might be a blood test for depression as there is for high cholesterol, thyroid problems or HIV.

Blood biomarkers to diagnose depression?

with Professor Eva Redei, Northwestern University

24:11 - Dieting your way to an eating disorder

Dieting your way to an eating disorder

with Philip Cowen, Professor of Psychopharmacology Oxford University

Hannah - Closing the show, have you ever been on a diet? If so, notice feeling a bit  ratty, anxious, low and then start to fixate on food? It certainly happened to me.

ratty, anxious, low and then start to fixate on food? It certainly happened to me.

Georgia Mills spent some time with Philip Cowen, Professor of Psychopharmacology, who was awarded the British Association of Psychopharmacology Lifetime Achievement Award. He whetted his academic appetite by uncovering the dieting brain. Like Lesley, he has also worked extensively studying depression. He starts off by discussing his views and hopes for depression treatment in the future.

Philip - I think people talk more about having been depressed and that's always very helpful because I think you can feel very alone with it. And to know that others have felt the same have suffered and have improved can be very heartening. At the same time, I think there's been quite a lot of publicity about the negative effects of antidepressant treatment particularly in medications and that's been hard for some patients. One hears various claims about them such as antidepressants don't work or they might be addictive. I think more recently, they do more harm than good. When people hear that, this obviously can be distressing if you've taken an antidepressant and it's helped you. I think we understand a lot more about neurocircuitry. We understand more about the brain basis of depression. I'd have to say, the treatments haven't changed all that much and that's been rather a disappointment.

Georgia - What would you hope to change now in the treatment of depression?

Philip - I would hope that in understanding the brain basis and the neurobase of depression might lead to better treatments. Actually, perhaps more in the psychotherapeutic line and in the drug line, and the way that one might be able to train different parts of the brain to respond in a more appropriate or less distressing way to environmental input. So, in a way, it's like more traditional psychotherapies, but guided by modern neuroscience.

Georgia - So, would you advocate a step away from chemical treatments and drugs?

Philip - I think that will always be useful for patients who don't respond to psychological methods. But I think there's a general tendency to say that psychological treatment should be first line where they're available and I would support that. At this meeting, there's been a lot of work discussed on the role of inflammation in depression. That's a very interesting idea and it gives rise to some potentially new treatments which might help those patients who don't respond very well to what we have now. So, I find that exciting.

Georgia - So, what is inflammation?

Philip - Well, it's a process which is part of many medical conditions, but it hasn't traditionally been linked with depression which is seen pretty much as a psychological disorder or a brain disorder. But it's now clear that inflammation can affect the brain and it certainly can affect mood. And so, this is a good line to work on if you're trying to come up with some new treatments.

Georgia - And as well as depression, you've worked on eating disorders and the causes of these. Can you tell us a bit about that?

Philip - Well, my work there was carried out with my colleagues Chris Fairburn, and Guy Goodwin and we were interested in the effects of dieting because eating disorder start as normal dieting which gets out of control. And what we looked at was the effect of dieting on a brain neurotransmitter called serotonin. Serotonin is very involved in mood and appetite. And we made a connection between dieting and serotonin effects. That gave an explanation as to why in some people, dieting can lead to eating disorders by acting as a kind of trigger through its effects on serotonin. Dieting is a statistically normal behaviour even though it may not be particularly wise if people overdo it. without meaning to, if you lower brain serotonin levels through dieting, that can lead to lower mood and more compulsive behaviour. So, the dieting really gets a grip on you and it's very hard to stop.

Georgia - And the treatment of these, would you recommend psychotherapies?

Philip - I think they're the main stay for all kinds of eating disorders and it really consists of going back to a normal diet and retraining yourself to eat in an appropriate manner. Often underlying eating disorders are rather negative use, people have of themselves and they need to be worked on as well which again, I think is best done psychologically. Over my career, the big change is being this idea that the brain has some plasticity, that it can change, it can learn, and that gives enormous encouragement for thinking of new psychological treatments to help people who spent long periods in their lives feeling pretty terrible.

Hannah - So, we can all feel optimistic about our flexible brains. Well unfortunately, that's all we have time for in this episode. Thanks to all those in the programme, Philip Cowen, Lesley Cousins, Michael Bloomfield and Kristen Brennand. This is a Special Naked Neuroscience episode reporting from the British Association of Psychopharmacology 2014 Meeting in Cambridge.

See you next month to open our minds.

Related Content

- Previous Can you be born circumcised?

- Next Worrying world population

Comments

Add a comment