From precious coral and slimey sea cucumbers to luxury fish lips and beautiful seahorses, this month Naked Oceans explores the many ways we trade the oceans. We sift through some of the highest price-tags in the sea and find out what impact this all has on ocean life. Helen pays a visit to an aquarium that breeds seahorses and finds out how to mail them around the world. And we ask, Is Blue Carbon the new green? Will converting marine life into carbon credits help fend off climate change? And in Critter of the Month we meet a very rare animal, with a very big appetite.

In this episode

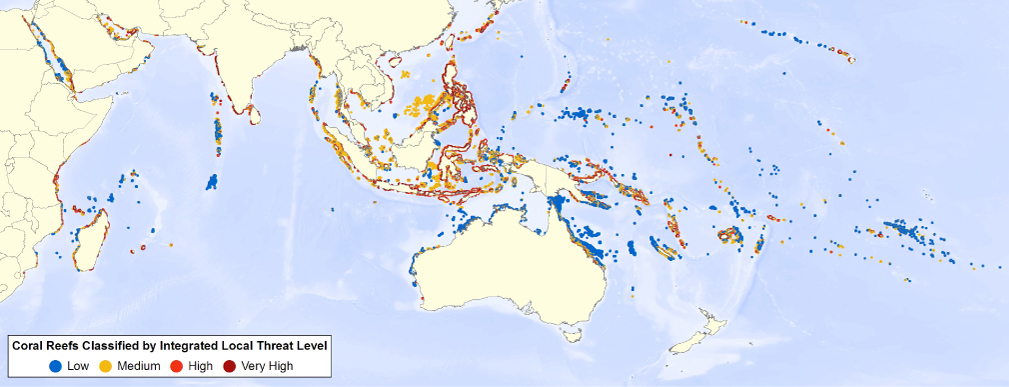

01:42 - Reefs at Risk Revisited

Reefs at Risk Revisited

Helen - This month saw the launch of a major new report on coral reefs. Reefs at Risk Revisited has compiled a detailed global map of the problems these vital ecosystems are facing today.

The report was launched this month at a special meeting at the Royal Society in London, and I went along to meet some of the people behind the report.

The main headline findings are rather depressing. One of the report authors is Mark Spalding from the Nature Conservancy.

Mark - The top headline is that 75% of the world's coral reefs are now threatened by human actions. That includes a combination of the direct imapcts of people on reefs, things that we can control really at relatively local levels. Those direct impacts are affecting 60, just over 60% of the world's reefs. When we factor in recent climate change, this is what's happened to date, not the future, that pushes our number up to 75% of the world's reefs.

Another headline that we looked at was predictions of the impacts of future climate change. And we sat those, if you like, on top of the results of threat to date, and they become extremely gloomy. By the 2030's we're up to 80% of the world's coral reefs being threatened and by the 2050's we're at 99%.

You can't stick your head underwater everywhere in the world, there's to much, there's not enough scientists, some of these places are very remote. So instead we've built a model which predicts how much is threatened and we've had that verified by hundreds of scientists from around the world.

Helen - And in terms of what's causing this risk to reefs, what are the threats we're looking at? What are reefs suffering from today?

Mark - It's a huge host of threats, really and quite often one piled on top of another. The biggest one is certainly unsustainable fishing. Just taking too much and sometimes taking it in extremely damaging ways using explosives to catch fish.

On top of that we have what's washing off the land. We have sediments and pollutants just being washed out of agricultural areas, from deforested slopes, into rivers and out onto the reefs. So that's kind of the watershed threat.

Then we've got coastal development. Human populations are burgeoning everywhere but particularly in the coastal zone. And as buildings are built and sewage is pumped into the ocean, that's a huge threat.

And the final local threat is shipping and other sources of marine pollution, oil and gas installations, boats cross-crossing the oceans and so on.

And sadly what we've added to that, already that long litany of threat, is the issue of chancing climate, changing oceanography.

Helen - And talking about reefs at risk, what does that really mean? Are we talking the reefs that are at risk aren't going to be here in a number of years time? How do we get a handle on what that actually means in the real world?

Mark - We need to remember this is a mode. We're trying to predict the condition and if you stuck your head under the water in many of these places you'd see different things. In some cases it is a measure of things already declining but in all cases it's a measure of potential for decline that could be any day, the pressures are immense.

Helen - Mark Spalding there introducing the key points raised by the Reefs at Risk Revisited report about the threats facing coral reefs today.

This new report follows on from a previous Reefs at Risk report that originally took on the challenge of painting a global picture of coral reef threats. Kristian Teleki chaired the Reefs at Risk Revisited launch. I spoke to him about how the whole thing got started.

Krisitian - Reefs at Risk got started in 1996-1997 when a number of scientists got together and were concerned that they weren't having enough information about all the things that were happening around the world on coral reefs. So they got together and they thought let's put this analysis together and we'll do a quick assessment of the entire world's reefs and are they are threat based on these different levels of threat indicators.

And that came up with some really useful statistics, and it actually boiled it down to these two or three key statistics that were cited over and over again. And we know that it's been cited over 400 times in the scientific literature, but it's been cited thousands and thousands of times and I remember seeing this constantly being recycled in the press in the media about these statistics.

And so really it was in thinking, in my previous job as the director for the International Coral Reef Action Network, that this was a great opportunity to revisit these statistics and update them. Because a lot has changed, both in the ecosystems, in the climate, and at a political level. So it was really important to go back and have a look at this but also not only compare the statistics but revisit some new nuances about social vulnerability, climate change, ocean acidification, these key threats to the importance of coral reefs.

So, it really was the revisited that we thought that this would make a really interesting story to revisit these old statistics.

Helen - And I assume, am I right that generally the changing picture since '98 is one

Kristian - Sure, I think there's been a general net decline in reef health, there's not doubt about that. You don't have to be a rocket scientist to go out and look and see that there's an impact.

I think the message is that it's not a straightforward story. I remember when we did work in the Seychelles in 1998 during the peak of the bleaching event, we went out in the southern Seychelles and we actually found that there was a lot of heterogeneity and mixed responses in terms of the bleaching event. Some reefs were bleached, some died, some didn't. And in fact, that told a very interesting story because when we came back the big story was all reefs are dying in the Indian Ocean, well that wasn't actually true.

So, I think what this report highlights is that there are pockets and areas that are resilient for one reason of another, they're doing well for one reason of another, and we really need to look at those very carefully as potential seed banks for other parts of the ocean.

So, I think what this report highlights is that there are pockets and areas that are resilient for one reason of another, they're doing well for one reason of another, and we really need to look at those very carefully as potential seed banks for other parts of the ocean.

Yes, while the net message is a depressing one, I think we're finding more and more cases where there are areas of hope and we really need to look at those carefully, because we can do something about it.

Find out more

Reefs at Risk Revisited website

Reefs at Risk Revisited report (Download PDF)

Interactive global map

08:54 - Top ocean price-tags

Top ocean price-tags

with Helen Scales and Sarah Castor-Perry

Sarah - This month on Naked Oceans we're diving into the many ways we trade the oceans, because there are all sorts of marine species that become incredibly valuable and sought-after once they've been caught and brought on land - and when there's lots of money to be made, people will of course go out and catch as much as they can until wild stocks start running out.

We thought we'd give you a run down of some the highest price-tags in the oceans. So, Helen what have we got to start things off?

Helen - Well, a lot of the top-priced ocean wildlife is, as you might guess, stuff that we eat. And some of it is really quite weird.

I did my PhD on a giant denizen of coral reefs called the humphead wrasse, and yes, the adult males do have big bumps on their heads. Some people say they're ugly, but I happen to think they are really very beautiful. And in Asia they are something of a delicacy. They feature in restaurants lined with aquarium tanks packed full of live fish so that diners can pick out the fish they want to eat just moments after it's whisked out of the tank.

One of the big problems is that many large reef fish like humphead wrasse are caught using cyanide. Divers swim down, squirt just enough cyanide to stun a target fish, and then they bring it back up to the surface and hope that it revives. And the thing is that cyanide lingers on the reef where it kills all sorts of other marine life. And it's one of the destructive fishing methods highlighted by the Reefs at Risk Revisited report as being one of the top threats to reefs.

Sarah - I mean Cyanide is very Agatha Christie, dastardly murder! It's not exactly the sort of thing you'd think you'd want to put onto a reef, that doesn't sound like a very good idea at all. I know you worked on them, but have you ever tried eating humphead wrasse? Are they nice? Do they taste good?

Helen - Well, actually no I haven't tried them. I always said that I wouldn't pay my own money to buy one because that just felt wrong, but if someone offered it them I would give it a go, but that never happened. So no I haven't tried them.

I heard they, obviously people do like them and the ultimate luxury, which is really weird I think, is a plate of their lips. They sell for hundreds of dollars. The males, these huge males, because they change sex they start life as females and become males as they get bigger, and they have these enormous lips, and people like to eat their lips. Weird! Very gross I think.

I heard they, obviously people do like them and the ultimate luxury, which is really weird I think, is a plate of their lips. They sell for hundreds of dollars. The males, these huge males, because they change sex they start life as females and become males as they get bigger, and they have these enormous lips, and people like to eat their lips. Weird! Very gross I think.

But there's another luxury seafood with a really high price tag that I have tried, and that's sea cucumbers, those tubular relatives of starfish.

Sarah - Well, funnily enough because I have actually tried sea urchins, which are another relative of the sea cucumber and I tried them in Japan and they were every strange. I'm not sure I'd really like to eat sea cucumbers, though, because they're sort of tubular and brown, and they don't really look like something you'd really want to eat.

Helen -Yeah, actually I've seen them being prepared, they're being fished out, then you have to boil them for hours to break down the tough walls inside them, and smoke them and dry them, and they do look pretty disgusting by the time they're done.

And then, I ate them while I was at a Chinese banquet in Malaysia and before I could say no someone had loaded my plate full of these slimy lumps, and I have to say they were really quite hard to chew and swallow, it was disgusting. They don't really taste of anything though, it's just that texture.

But, so I certainly, personally, couldn't imagine why you'd want to eat echinoderms. But they are considered quite the delicacy, and a growing number of people around the world think they're fantastic and sea cucumbers are one of those foods that supposed to be very good for you, they've even made anti-wrinkle creams out of them, and some people think they're at aphrodisiac.

Sarah - So, are they quite an expensive thing to buy then?

Helen - Yeah, so supposedly the most expensive soup in the world is something called "Buddha Jumps Over the Wall" and that contains various ingredients including sea cucumber and sharks fin, and the story goes that it smells so good that it would even tempt vegetarian Buddhist monks to jump over the monastery wall to try some.

Sarah - That sounds actually really disgusting, uh, no I'm not convinced by that. Not to mention the fact that it would be really bad for all the species that are involved.

Obviously people eating all this stuff and it being really popular, obviously the use for anti-wrinkle creams, and you know, it's great for you, is that causing problems for them in the wild?

Ok, so lots of people are eating sea cucumbers today - is this causing any problem for these slippery critters in the wild?

Helen - Well, yes. The problem is, as you might imagine that catching a sea cucumber is very easy. You don't have to do much more than just swim down and grab it off the sea bed, or dredge them up.

And what we've seen in the past few decades as there's been this increasing demand for sea cucumbers is a kind of boom and bust with fisheries opening up in new areas, fishermen cleaning out all they can find, and then moving on to the next place. So we've got this global trade marching around the world, hoovering up sea cucumbers as it goes.

But to be honest we can find some good news in all this, which is that we are becoming more aware of what's going on, and people are starting to talk about putting in measures to help protect sea cucumbers, because the are hardly, like we said, the most loveable of invertebrates. But there are even a few marine reserves being set up specifically for sea cucumbers including the Lau Lau Sea cucumber sanctuary in the Northern Mariana Islands in the Pacific, and you can check out on the Protected Planet website we mentioned on Naked Oceans a couple of months ago and we'll put a link to that on our website.

Sarah - So, obviously there's a bunch of high-priced marine species that aren't doing very well in the wild because the demand for them is increasing, so things like sharks caught for their fins, you've got the bluefin tuna that are sold for huge amounts of money in Japan to make sushi, and oysters as well, which we talked about on Naked Oceans last month.

But it's not just about the things that we eat that get traded is it?

Helen - No absolutely. There's also lots of stuff we'll pay top dollar for because they look pretty. Obviously pearls are one of the most ancient jewels and they come from the oceans, they do come from freshwater pearls as well, but there are marine ones, like the fabled black Tahitian pearls.

Helen - No absolutely. There's also lots of stuff we'll pay top dollar for because they look pretty. Obviously pearls are one of the most ancient jewels and they come from the oceans, they do come from freshwater pearls as well, but there are marine ones, like the fabled black Tahitian pearls.

And like you say, with declines in oysters around the world, wild pearls are extremely rare and amazingly expensive these days.

And there's another gemstone that grows in the sea and that's coral. Since ancient times people have made jewelry and ornaments out of red, pink and black coral. And these aren't corals that build reefs in shallow waters, but they live in the deep sea and they grow branching, tree-like skeletons made from really dense calcium carbonate that can be cut and polished and it really does look quite beautiful.

Sarah - And those are the ones that get their Latin name from Medusa, the snaked-haired gorgon in the Greek myths?

Helen - Yeah exactly, the story goes her blood dropped into the sea and turned some seaweed into coral, and so there's a big group of corals called gorgonians.

But these days, many deep sea corals are being overexploited in many parts of the sea and conservationists are urging people not to buy and wear coral any more. And there are also efforts underway to have red corals listed on CITES, that's the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species, and that would help to regulate and monitor the trade.

But really, I think what this comes down to is a lot about us as potential customers and consumers, and we're the people who, we can buy and we can decide what to eat and what to wear. And if we don't agree with exploiting corals or sea cucumbers, or whatever then we can make our say by not buying them.

Sarah - Yeah, I think there definitely is a bit role for consumer, people pressure to play, you know pressuring supermarkets and retailers of things like fish or things like coral jewelry and things, not buying specific things or calling for, right we want regulation, we want the fish that you sell to be regulated by the Marine Stewardship Council, or we want to make sure it's caught safely, and caught in a sustainable way. So I think definitely consumer pressure is going to play a big role in the future of that.

Find out more

Too Precious to Wear - Seaweb

Sea cucumbers - A global review of fisheries and trade. FAO.

Lau Lau sea cucumber sanctuary - Protected Planet.

Humphead wrasse (Cheilinus undulatus) on Fishbase

Monitoring the live reef food fish trade - Live Reef Fish Information Bulletin (PDF)

16:43 - Is Blue Carbon the new Green?

Is Blue Carbon the new Green?

with John Bruno, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill

Sarah - Buying and selling things we find in the oceans isn’t all about food and jewelry, and it doesn’t necessarily have to be a bad thing for marine life. Finding value in marine species and ecosystems can sometimes help to create incentives to protect them.

Around the world, efforts are underway to protect vital habitats that fringe the edges of the oceans – mangroves, wetlands, seagrasses and so on – by capitalizing on their ability to lock up carbon. We’re getting used to the idea of trading forests for their carbon, but now there are hopes for an emerging market in blue carbon.

To find out more Helen chatted with John Bruno, from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

John – Blue Carbon is what scientists call coastal vegetation including mangroves, salt marsh grasses, and seagrasses. And all three types of coastal vegetation are wonderful at sequestering carbon dioxide, so that is pulling carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere, simply through photosynthesis, they turn it into organic carbon, and they essentially move it down into their roots.

Unlike terrestrial plants these types of communities accrete vertically so they grow up vertically, sometimes at really high rates, like a cm or so a year. And so as they grow vertically they just store more and more carbon dioxide that’s been transformed into organic carbon below them. And they can do that for centuries or even much, much longer. And because they’re in salt water that carbon is not exposed to air so it doesn’t get broken down by bacteria and respired back into the atmosphere.

Both conserving blue carbon habitats and also restoring and replanting them is one of the really low hanging fruits as a solution towards mitigating the impacts of climate change.

And the wonderful thing is it has all these add on benefits. All three habitats serve as really important nurseries for all kinds of fish that are caught commercially in fisheries. They’re wonderful in protecting coastlines from erosion, so they’ll actually mitigate the effects of climate change such as sea level rise and increased intensity of storms. And they can create jobs for people just by enhancing fisheries production, so it’s really a win-win situation.

So there’s several groups all around the world that are trying to figure out how to fund the conservation and restoration of blue carbon through carbon trading markets and other activities and mechanisms.

Helen – Because these habitats are already in quite big trouble, aren’t they? We’re loosing them at a really astonishing rate?

John – Yeah, so the estimates are somewhere between 1-5% per year for each of these habitat types, and that’s substantially higher, probably 2-4 times higher than we’re loosing tropical rainforest at. So we’re loosing them really quickly and in the case of mangroves it’s primarily due to clearing for shrimp farms primarily but in some cases other types of development, putting up condominiums, or resort areas.

For seagrass, the main driver of loss seems to be water quality. So, sediment pollution, sedimentation from terrestrial development and also eutrophication, so the pollution by nutrients seems to be killing off seagrasses.

Salt marshes it’s really again about land development, people putting up sea walls in front of the marsh to protect their property, or marshes being wiped out for development.

Helen – They suffer a bit from a charisma gap don’t they, these habitats. We don’t really hear much about them and yet they’re really important. Are they as important as rainforests in terms of how much carbon they can lock away or other sources of carbon sinks?

John – They’re almost as important as rainforests in terms of the actual rate of sequestering carbon. So, of course there’s many times more area coverage of rainforest on the planet, but these blue carbon habitats sequester carbon about a hundred times faster than rainforest or other types of forest do.

So in terms of playing that role, it’s about a one to one, so both types of habitat play the same role. But you can conserve or restore one one hundredth of the area of a blue carbon habitat and get the same result in terms of carbon sequestration and storage.

Helen – And where would you say we are at with blue carbon right now? Is this something that we’re going to really need to work hard at? Or are we already catching onto this idea?

John – I think at least in the scientific community and the NGO kind of development, conservation community, there’s been much more awareness of it just in the last six or eight months. So the UNEP released a really fantastic report just before the Copenhagen conference and there are several working groups being put together by Conservation International and the UN and a couple of other groups. So there seems to be headway going on.

As far as I know there’s actually no projects being funded by any of the carbon offset markets and that’s one of the really tricky things is that the markets aren’t really designed for this kind of project. Most carbon offsetting occurs through things like wind and solar power, methane recapture through landfills, and frankly primarily through Chinese hydroelectric projects. So the market is really geared towards those kind of projects, so there’s a lot of work going on trying to figure out really how to incorporate the blue carbon into that regulatory marketplace.

Sarah - That was John Bruno from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill giving us the low down on Blue Carbon.

And it’s going to be really interesting to see how this idea develops. Since we spoke to John, he’s been working on some pilot Blue Carbon projects in Ecuador helping shrimp farmers to replant areas of mangrove that were cut down to make way for their farms – and hopefully replanting will be something the farmers can make money from.

And just a few weeks ago, a group of leading conservationists and scientists held a meeting in Paris to discuss Blue Carbon and figure a way of taking it forwards. So I’m sure this is something we’ll come back to here on Naked Oceans.

22:51 - Supplying the seahorse trade

Supplying the seahorse trade

with Shawn Garner, Mote Marine Laboratory

Helen - Every year millions of dead seahorses are traded as Traditional Chinese Medicines. They're thought to be a remedy for all sorts of conditions from broken bones and asthma, to kidney complaints and even a flagging libido, and conservationists are worried this is putting too much pressure on some wild populations.

There is also a roaring trade in live seahorses for public aquariums and for people who want to keep them at home as pets.

There is also a roaring trade in live seahorses for public aquariums and for people who want to keep them at home as pets.

So, I paid a visit to Mote Marine Laboratory in Sarasota in Florida, to find out how breeding seahorses in captivity is offering a way of cutting down on the number of seahorses we take from the wild every year.

Here's supervisor of Mote's Seahorse Conservation Lab, Shawn Garner.

Shawn - This is a laboratory that's on exhibit to a public aquarium 300...

Helen - In fact we can see people walking right by now, peering in the window...

Shawn - And waving, yes. So education is key. We want to show children and adults  seahorses because it is the coolest animal in the world.

seahorses because it is the coolest animal in the world.

Helen - I'm glad you agree with me on that.

Shawn - There's no other animal that has a head like a horse, eyes like a chameleon, pouch like a kangaroo, tail like a monkey. And it's a fish that has the only true male birth. That is the coolest.

But the really main thing about this laboratory is breeding seahorses, learning how to do it, and sharing that information with other facilities so that they can breed seahorses.

We're breeding them for other zoos and aquariums around the country do they don't have to collect from the wild.

Helen - That's great, so how long will you keep seahorses here before you send them off to other aquariums?

Shawn - We wait for about 6 months, 8 months is ideal when we ship. And we ship all around the country and hopefully around the world sooner or later.

Helen - How do you send a seahorse? You send them by plane I take it?

Shawn - Yeah, actually we use Fedex. We put it in a bag of water, one third really clean water, two thirds pure oxygen. I put 3-4 seahorses in a bag and I give them a toy. Because anyone who has driven around with kids in the back, they hit each other, they mess with each other, and I don't want that stress. So I give each seahorse a toy to hitch onto and that's kind of like their protection.

And then they're triple-bagged, put in a Styrofoam shipping container, then there's a heat pack or cool pack, and we ship them overnight. We've shipped a thousand or more seahorses and maybe had one problem but it's been really good, and the horses arrive there perfect.

What we're looking at is the brood stock. And the brood stock means that they're animals just for breeding. They're here, they're my best seahorses right now.

Helen - They're the studs?

Shawn - They're the studs, and the queens, I guess. They have good genetics. They're usually wild caught. Now I'm legally allowed to take a few wild caught seahorses from the environment. So really all they're here doing is breeding and eating. And it happens in the morning. They go up in the water column, they either do their mating dance or they transfer eggs, and then they kind of leave each other alone the rest of the day.

Helen - And, how often will they actually have babies?

Shawn - The male will get pregnant, of course. His gestation is about 25 days. He will release the babies and pretty much the next day or two days after, he's pregnant again. And this happens pretty much his entire life from 6 months all on up to about 4 years, and he is pregnant most of his life.

Now, he gets pregnant so much he can actually fake being pregnant.

Helen - This is news to me!

Shawn - Yeah, he can actually inflate his pouch with water and tell his girlfriend or his wife 'I'm pregnant already, I can't accept your eggs this month'. And she will actually dump her eggs on the ground, which is terrible because it takes 40% more energy to create the eggs than to gestate them.

Helen - Wow, that's crazy. Okay, so we have, these are the mums and dads basically. And then the babies come, and then these are the guys over here? These are some of the newborns in this tank? Well, you haven't got any tiny ones, but these ones here?

Shawn - Yeah, we didn't have seahorse babies last week, but we had some two weeks ago and we're looking at them right now. It's a brood of probably 100. We're looking at Hippocampus erectus, the lined seahorse.

Shawn - Yeah, we didn't have seahorse babies last week, but we had some two weeks ago and we're looking at them right now. It's a brood of probably 100. We're looking at Hippocampus erectus, the lined seahorse.

So what they're doing is they're circulating around the tank. They're in a specially designed tank called a Kreisel or Gyro, and it's a tank designed for animals that are planktonic, that are floating in the ocean, we like to tell the kids planktonic means 'Go with the flow'. So they're circulating and they're eating the smallest food that we have, and we actually grow plankton here. And they're eating it and they're swimming and that's all they're doing right now.

Helen - And in this tank here there are some equally as tiny animals, but they're a bit older, aren't they?

Shawn - Yeah, these are Hippocampus zostera, the pygmy seahorse. And, very small animal, one inch is pretty much max. They only have 10-12 babies at a time, but they have one of the largest babies of any other seahorse, and they're pretty smart. There are so smart that when we try and take them out of their parent tank they can run away from the net. They know a net is danger. They're very smart animals, I love these guys, they're so cute.

Helen - They are amazingly cute. They're so tiny I can hardly see them. Awesome.

Seahorses are pretty sensitive aren't they, to their conditions in which they're living. The water has to be the right salinity, temperature and so on, and they are kind of susceptible to getting diseases too, that's the case, right?

Shawn - Like any animal they can get stressed out. Just like humans, you get stressed out, and when you get stressed out you're more prone to getting a cold or the flu or what have you. Yeah, seahorses are very prone to diseases and bacteria. So we try to provide the most calm environment for them.

We found out lately that sounds are huge in the seahorse world, that load sounds, motor sounds and vibrations from the world causes seahorses to become stressed out which I turn gets them not to reproduce as much, not live as long.

When we built this lab we specially chose the pumps, the lighting, all the filtration so that everything is vibration-free, there's not a lot of metallic sounds in the water. And it's really, hopefully, proven to be a great thing. A lot of zoos and aquariums have big tanks that have really strong pumps and concrete and vibrations, they have a lot of problems keeping seahorses alive. Well, we keep them alive and we breed them in their thousands. So, I think the vibrations and the sounds are really important to seahorses' survival.

everything is vibration-free, there's not a lot of metallic sounds in the water. And it's really, hopefully, proven to be a great thing. A lot of zoos and aquariums have big tanks that have really strong pumps and concrete and vibrations, they have a lot of problems keeping seahorses alive. Well, we keep them alive and we breed them in their thousands. So, I think the vibrations and the sounds are really important to seahorses' survival.

Helen - You've been operating on seahorses?

Shawn - Not me, but we have a vet that actually did one of the first laser surgeries on a seahorse. We had one seahorse a year or two ago that grew a tumour on its tail.

What we did is, we grabbed the animal, and we actually put it under, under anesthesia.

Helen - Oh my gosh, how did you do that?

Shawn - We took it out of the water, and put it on a tray and ran a tube into its mouth that pumped anesthetic water and it went right past his gills and put him under. He was dry but he was still breathing and he was knocked unconscious.

And so the vet got the laser out, turned the setting to the lowest setting because he was so worried how frail a seahorse is. And tried to take the tumour off - didn't work. So he raised the level up a little bit more - no go. He had to raise the level up so high it was the same as turtle shells, and then he was able to take the tumour off. And so we took that seahorse and put him back in his regular water, he woke up, and he survived another year or two after that. It was amazing, it was so neat.

Helen - That is very cool. Seahorse hospital, here we are.

Shawn - Yeah, we'll do anything to keep them alive. It's important.

Find out more

Mote Marine Laboratory

Hippocampus zostera on Fishbase

Hippocampus erectus on Fishbase

31:27 - Critter of the month - North Atlantic Right Whale

Critter of the month - North Atlantic Right Whale

with Mark Baumgartner, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

Mark - My name is Mark Baumgartner, I work at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in Massachusetts and I am a biological oceanographer. And if I were a critter, a marine critter, I'd be a North Atlantic right whale.

The reason I would be a North Atlantic right whale is because I like to eat. And the job, the most important job of a right whale I think is eating.

They eat a lot, they eat often.

They eat a lot, they eat often.

They have a funny way of eating. They have very large heads, and basically their mouth is a net and they catch plankton And the things that they feed on are about the size of a flea. And so they need to eat a lot. In fact, we estimate that they have to eat 1-2 billion of these creatures every day. These creatures are called copepods, they're little crustaceans, a lot like a crab or a lobster but much, much smaller, the size of a flea.

So in terms of, so to put that in terms that we can understand that's about 3000 big macs, every day. Or the weight equivalent of a Volkswagen Beetle, in food every single day. So, I like to eat, right whales like to eat, that's great.

In the ocean, it's eating or it's being eaten. And so size has a lot to do with whether you're going to get eaten or not. And for the whales they have very few predators because they're very large. So, as a whale you would be less prone to being eaten by anything but you'd get to eat all the time.

So, that's not to say that right whales don't have problems. They have some serious  conservation issues in the North Atlantic. They tend to get hit by ships and get entangled in fishing gear and because their population is so seriously endangered, there's only about 400 right whales in the North Atlantic, this is a big problem for them. Just loosing one or two animals from the population, particularly females, is a big problem.

conservation issues in the North Atlantic. They tend to get hit by ships and get entangled in fishing gear and because their population is so seriously endangered, there's only about 400 right whales in the North Atlantic, this is a big problem for them. Just loosing one or two animals from the population, particularly females, is a big problem.

So, life is not all fun and games for right whales, they have these interactions with right whales that tend to be not so good for them. But there's a lot of work being done on that front, there's a lot of good will on the part of the shipping industry, the fishing industry.

It's pretty clear that there is a problem and people really want to solve the problem, and there's a lot of good people, both scientists, government scientists, policy-makers, and people from the industry that want to improve the prospects of North Atlantic right whales and there's been a lot of good work done, including moving shipping lanes and changes to fishing practices.

So I think the outlook for right whales is actually quite good, the population has increased over the past decade. When I started studying right whales they used to say there's probably only about 300 whales and now there are 400 whales which is given me a lot of hope for the species.

Find out more

Mark Baumgarnter's lab at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

North Atlantic Right Whale Consortium

Related Content

- Previous Why did a Laser Make My Nuts Glow?

- Next Reefs at Risk Revisited

Comments

Add a comment