This special Naked Scientists comes to you from the MTN Sciencentre in Cape Town, South Africa, with some of the highlights of SciFest Africa. Meera goes on safari to find out how the Born Free Foundation re-home mistreated lions while Chris tracks the Black Rhino to discover how to conserve this critically endangered species. We find out how the Naked Scientists live science show, Crisp Packet Fireworks, wowed and inspired the festival's visitors. Plus, the story of the Coelacanth, tackling TB and Ben and Dave have an explosive Kitchen Science!

In this episode

01:21 - Safari in Shamwari

Safari in Shamwari

with John O'Brian

Meera - I'm at the Shamwari Game Reserve in Port Elizabeth in South Africa. Shamwari is one of the largest private reserves in the country, hosting the big five animals: lions, leopards, rhinos, buffalo and elephants. It's a beautiful day here today and I'm at Long Lee manor, one of the many lodges that you can stay in here. I'm here with John O'Brian, the Group Ecologist for Shamwari. I can see a vast expanse of land from here. How big is Shamwari?

John - Shamwari's between a total of 7 and 5 thousand hectares. It's a substantial piece of land and the majority of it is natural vegetation. It is historically old agricultural lands that we've had to restore.

John - Shamwari's between a total of 7 and 5 thousand hectares. It's a substantial piece of land and the majority of it is natural vegetation. It is historically old agricultural lands that we've had to restore.

Meera - You're quite lucky in that you have a written record of the animals that used to be here.

John - There's a place on Shamwari which crosses the Bushman's River. The Bushman's River runs for about 29km through the reserve. It's the only place that you could cross the river historically by ox wagon. As a result all your early hunters, explorers used to cross there and actually camp on the banks of the Bushman's River, right on the property. Then they'd reference to all the animals they saw or shot or whatever it may have been in the early days. Somebody has actually gotten together and compiled all those notes into a book. From one book we can determine what was historically in the area.

Meera - What is involved in managing a place like this?

John - I think in essence it's - we want to be sustainable in the long term on a few fronts. First of all: ecologically. In other words Shamwari's got to be in better condition two years down the line than it is now. Second of all, we want to be sustainable financially because we are a private game reserve. We don't get subsidies. Then the third aspect is we need to be sustainable socially. When I say socially I don't just mean for the people in the area. I'm talking about South Africa. Anybody who owns land in South Africa must make sure it has a positive contribution to the economy and the social issues of the country.

Meera - As well as making the reserve sustainable in terms of the people coming here and things like that the conservation and the ecology side is obviously very important. You have to control the plants here in order to provide the food for the herbivores and then you also need to control the predators having their prey. What are the techniques or methods you use to monitor this?

Meera - As well as making the reserve sustainable in terms of the people coming here and things like that the conservation and the ecology side is obviously very important. You have to control the plants here in order to provide the food for the herbivores and then you also need to control the predators having their prey. What are the techniques or methods you use to monitor this?

John - That is probably the most important thing - the balance. The most important monitoring concept we have is the vegetation management. In essence that is what controls everything. With no vegetation you've got no herbivores and you've got no predators either. In this area some of the vegetation's very sensitive and if ruined or degraded completely it can take anything from 3-5 hundred years to regenerate itself. We have a vegetation monitoring system. We have a predator monitoring system where we monitor the impact of the predators on the prey. Then we've got various environmental monitoring systems to do, water monitoring. In essence we do annual game counts and just making sure that the system is functioning.

Meera - What do you actually do to monitor?

John - With the vegetation monitoring, for example, we have 91 fixed point sites on the reserve where we have a statistical scientific way of determining change in the vegetation as well as fixed point photography. We do that annually and then try and assess the changes as positive/negative; if it is negative what is causing it and then try to rectify it. From a predator point of view we have a daily team that actually monitors the predators and records all the kills. From a human impact point of view we like to do a lot of work in terms of looking at the impact of lodgers etcetera on the water quality. We're permanently doing water tests and carbon footprint tests, those sorts of things.

Meera - Now we're going to go out and have a look at some of the keep plants and vegetation here and the herbivores that then feed on them. It's mid-morning so it's not a very good time to see predators in action really, is it?

John - Certainly not in action. They will be out there somewhere but the chances are they could be resting in the thicket, in the shade, maybe not necessarily viewable. Also animals have to be somewhere: elephants aren't too far from here.

Meera - Let's go and have a look...

We're just by a group of elephants now. What are these elephants up to at the moment? There's a group of them and I think they're mothers because there's lots of baby ones around.

We're just by a group of elephants now. What are these elephants up to at the moment? There's a group of them and I think they're mothers because there's lots of baby ones around.

John - yeah, this is a nice little herd. You always find that elephants are led by the matriarch, the eldest and wisest of the females. They're just slowly grazing as they go through this area but they're making their way to the river. It's approaching midday, it's getting warm so they're going to bathe in the river.

Meera - When it comes to controlling the numbers of elephants what are the things you need to think about here at Shamwari?

John - I think elephant are probably the most difficult. You can look at contraception, even doing vasectomies in males these days/. I think one of the biggest problems is that they have the potential to be one of the most destructive animals next to man. We monitor very carefully the impact they're having on the environment on Shamwari. We don't have an issue, everything's going according to plan and we're happy. One little thing though is that they love a specific tree: the cabbage tree. It's a nice soft tree that they specifically seek out because they love it so much. You often find that the cabbage tree will be in the middle of a big bush camp. They're destroy that whole bush camp just to get at that one cabbage tree. In essence their impact is fairly negative, I mean fairly minimal, rather.

Meera - We're off to another part of the reserve now.

John - Let's just go and see what's around. Somewhere very nearby here is a cheetah on a kudu kill. It's underneath a guarri tree. All we need to do is find the guarri tree and there we go. You see it over this side, it's actually feeding.

John - Let's just go and see what's around. Somewhere very nearby here is a cheetah on a kudu kill. It's underneath a guarri tree. All we need to do is find the guarri tree and there we go. You see it over this side, it's actually feeding.

Meera - Oh my god, yeah! Uh oh, it's spotted us. Does that matter?

John - No, they're very relaxed. It's feeding so it's got other things on its mind. Cheetahs aren't animals that are dangerous to humans.

Meera - We've pulled up alongside this tree and I can just see the cheetah's body and its head and its tail's wagging now. It is just, quite literally, having a feast down there: munching away.

John - You see this right atapan? The watering hole. It's probably hanging around here, the kudu came to drink and it killed the kudu. The first thing that it'll do is it'll drag it under a tree somewhere. That's for a couple of reasons. One: it's frightened. The other reason is to hide it from other scavengers or other predators like a lion. It'll probably feed it for the whole day.

Meera - Do they mainly feed on kudus or many other things too?

Meera - Do they mainly feed on kudus or many other things too?

John - Young kudu often are quite a high percentage of their diet. No they feed on a variety of antelope: all the way from duiker all the way through to adult kudu.

Meera - It just put its head up now and it's just got a mouth full of blood.

John - Yeah, you can see the mouth full of blood there. What a cheetah can do is they can actually feed on antelope. They never have to drink ever because they get enough moisture from the plants. The cheetah can actually, through the blood, get all the moisture it needs. It can go through a whole cycle of not having to drink water. With water yeah they do drink. They always start with the succulent parts around the rump and that's where they get the most moisture from and that's why the face is so red at the moment.

Meera - How are the cheetah populations here? Are they quite easy to control?

John - Cheetah are up and down. One thing is the cheetah is vulnerable to lion. The population is actually quite stable. It's working nicely, there is some youngsters around at the moment. It's working well.

Meera - I think let's leave it to finish off its lunch, I guess.

John - he's having a nice quiet feed so we'll leave him to it.

Meera - We've left the vehicle now and walked up into a higher part of the park; the southwest corner. One thing I've noticed is that the land around here is quite dry at the moment.

John - We've been having quite a difficult time of it of late with rain. We've been having rain but no follow-ups in between. It's a bit of a problem. We're quite concerned the river's very low. We had rain that saved us about three or four months ago because we were really dry. If we don't get a bit of follow-up now we are concerned, yes.

Meera - You've brought me to a particular plant here which seems to be very important when conditions are as dry as they are now.

John - Very much so. This area inland, this vegetation is what's known as a transitional subtropical thicket. One of the key characteristic species you get here is a 'speckworm' which means the bacon bush or fat bush. It's a succulent and why it's so important is that all though it's not utilised that much by animals during the good times it contains a lot of water. During the droughts it's this plant that actually saves the day. Animals really love it.

Meera - You've got a leaf here in your hand and you're breaking it apart and you're right it's filled with water.

John - Not only is it filled with water, it's filled with a lot of nutrients and you can actually use it in stews yourself. You should try one it's actually quite nice. You'd lose a bit of hair on your teeth but we munch on it every now and then ourselves when we have a hot day. This subtropical thicket is probably the best you can get in the world for elephant and black rhino.

As we walk back to the car: if you have a look you can see there is some hyena dung. You can see it's white because it's calcium. They eat the bones and fill the scavenger role. As you walk you can see a whole variety of antelope spore, warthog spore. Spore is basically tracks. Here you can see a line track. It's been slightly rained on so it would probably be from yesterday morning.

Meera - As well you can just see these small amounts of things just to figure out the movement of the animal?

John - Here you've got a millipede which you can see has walked over there with hundreds of little legs. Whenever you go round you're not only looking for animals, you're also looking for what animals have been here. That gives you a good indication of what's here, what's what and what's happening on the property.

Meera - An important issue when it comes to game reserves is the fact that the animals are contained. The land is fenced off. Does this affect their natural migration patterns that they would have had otherwise?

John - I think from a historical point of view but times have changed. Africa has changed. Certain movements have been restricted. You do get many migrations on a much smaller scale. Even in areas like central and Eastern Africa where animals still do migrate you do find you end up with human-animal conflicts. That is starting to be a big issue out there and Mozambique is sitting with the same problems at the moment. Where you get self-sustaining populations of people in terms of small maize fields and that sort of thing you're going to have conflict with elephant. Where you have pastorialism with cattle you are going to have problems with predators. You are finding that the animals are restricting themselves naturally to the protected areas. The other thing to think about in migration is sometimes migration is specifically with elephants it would have been over vast distances. They used to migrate from where we are now all the way down the garden route towards Mossel Bay, inland through the Karoo: hundreds of kilometres. Put that in today's society there'll be taking a ride through some major towns in South Africa. Obviously things have changed. Westernisation has taken place. The development is there and we've got to adapt our conservation methods to suit everybody including the animals.

12:56 - The Born Free Foundation

The Born Free Foundation

with Glen Vina, The Born Free Foundation

Glen - We rescue wild animals that are kept in inhumane conditions all around the world. We try to give them a better quality of life for a few years before they die. I like to describe this sanctuary as a retirement home. We have rescued lions and leopards here. It's cats that were rescued from run-down zoos, circuses, nightclubs. Sadly we cannot rehabilitate them and send them back to the wild. Some of them have lost their canine teeth; some of them their claws have been removed; some of them because they were not fed properly their bone structure didn't develop properly due to lack of exercise and not getting the correct food.

Meera - If they're going to live here they're going to need a lot of land in order to be comfortable and happy. They've been rescued from bad conditions. How big is the sanctuary here and how much land do they have?

Meera - If they're going to live here they're going to need a lot of land in order to be comfortable and happy. They've been rescued from bad conditions. How big is the sanctuary here and how much land do they have?

Glen - the enclosures here for our rescue cats each you're looking at about 1.5ha and we've left the camps totally natural.

Meera - how do you look after he animals once they're here? They have this 1.5ha of land to live on but what about their diets?

Glen - We feed them twice a week. We feed them with food that we get from our local farmers. Unfortunately they can't hunt for themselves because they were born in captivity.

Meera - How far and wide have you received animals from in the past?

Glen - Some of them came from Romania, Liberia, Sudan, The Ivory Coast, Greece.

Meera - And what about reproduction in these animals? You don't have that much land so you obviously don't want them reproducing?

Glen - Definitely. Especially in captivity, we don't want any cubs born in captivity. What we did - all our male lions have vasectomies - the snip - which means they still mate but there are no cubs born in captivity. The reason why we don't castrate them completely is that the testosterone is responsible for the growth of the mane. If you castrate them the mane falls off. Our lionesses, we put them on contraceptives. The reason for that, why we put them on contraceptives is that the wild lions in Shamwari will pick up their scent when they are in heat. If they are on the contraceptive they don't come into season. That keeps the peace between the animals.

Meera - In order to understand more about how you look after the animals here you're going to take me on a tour to see a bit of the land...

Meera - In order to understand more about how you look after the animals here you're going to take me on a tour to see a bit of the land...

We've come round the back and Sinbad the lion is here now.

Glen - Sinbad was fed on a diet of pasta and deboned chicken. His bone structure didn't develop properly so he's half the size of a normal lion, because he didn't get the proper diet from an early age and a lack of exercise. He's got no claws. Maybe when he started to scratch people they pulled the claws out. Then he lost his canines too but that was due to frustration while he was kept in that small cage. He was chewing on the metal bars. The canines broke off. They are the same length and height as the molars.

Meera - When the animals come here it must be a change for them because they've been mistreated and things like that. What do you have to do in order to introduce them to the sanctuary?

Glen - At first, before we release them into the big enclosure that's 1.5ha we keep them in a smaller enclosure which we call a hospital camp. That's where they'll acclimatise to the new environment, get used to the electrical fence. They have to dodge the fence to know or to respect the fence. Otherwise they can run straight through it. It's only electrified and it's got about 10,000kV running through it. It won't hurt the animal but just gives them a big shock. Sometimes it can take them up to 3 weeks, sometimes up to 6 weeks just to adapt to this environment. For some of the rescued animals, like Sinbad, that used to stay in a concrete cage; for him it took longer to get used to this environment. He wasn't used to the thorns. He wasn't used to the soil and he had to get used to the bushes and everything, stuff that he never saw, vegetation that he never saw in his life. It took him about three months to get used to this environment.

Meera - I can't stress how close to us this lion is. He's less than a metre away from us but there is a cage in between. He's very well-behaved. He's just sitting here alongside us.

Glen - Definitely. He's totally relaxed. As you can see he's busy just grooming himself but he must still be treated as a wild animal. It's just this fence that's keeping us away from him. Otherwise if we did something silly he could come through and devour us.

Meera - Ok - well I won't be doing that! We've now come round to where they leopard triplets are. They're all - well one of them over here just about a metre in front of us is sitting under a tree because it's very hot. What is the story with these leopards, Glen?

Glen - These three came from Sudan, found by the soldiers at the age of two weeks in the desert. I'm not sure what happened to the mother. She was probably looking for food or out on a hunt when the soldiers came across these leopards and picked them up and took them back to army camp. They wanted to use them as watch cats, maybe watch dogs at the camp. This one in front of us that's sitting under this tree his name is Elum, keeping cool. Here comes Sammy the dominant male. Hello Sammy.

Glen - These three came from Sudan, found by the soldiers at the age of two weeks in the desert. I'm not sure what happened to the mother. She was probably looking for food or out on a hunt when the soldiers came across these leopards and picked them up and took them back to army camp. They wanted to use them as watch cats, maybe watch dogs at the camp. This one in front of us that's sitting under this tree his name is Elum, keeping cool. Here comes Sammy the dominant male. Hello Sammy.

Meera - He's ignoring you.

Glen - He's just walking up to his brother now. Very social.

Meera - He's got a large area just hanging low from his belly. What's that?

Glen - Our cats, especially with the leopards they've been completely neutered. Once you do that, especially to the males, you remove all the hormones. That's why they get a bit big. They are not as active as a wild lion or leopard. Remember in the wild they will chase things. Here it's a much easier life.

Meera - Did they find it hard to adjust to being here?

Glen - I mean they came here when they were about 5-8 months old. Because they had each other's company probably it was much easier for them than the other rescue cats that came here.

Meera - So Born Free's doing a lot of good work here and looking after these animals. Are there any future developments at Born Free?

Glen - At this stage we're busy developing another centre. It's about 70km away from us. We call it the Gene Bird centre. Born Free's rescuing more cats and lions so we need another home for them. With that centre we can accommodate another 12 animals there now. I'd like to refer to what we're doing as compassionate conservation.

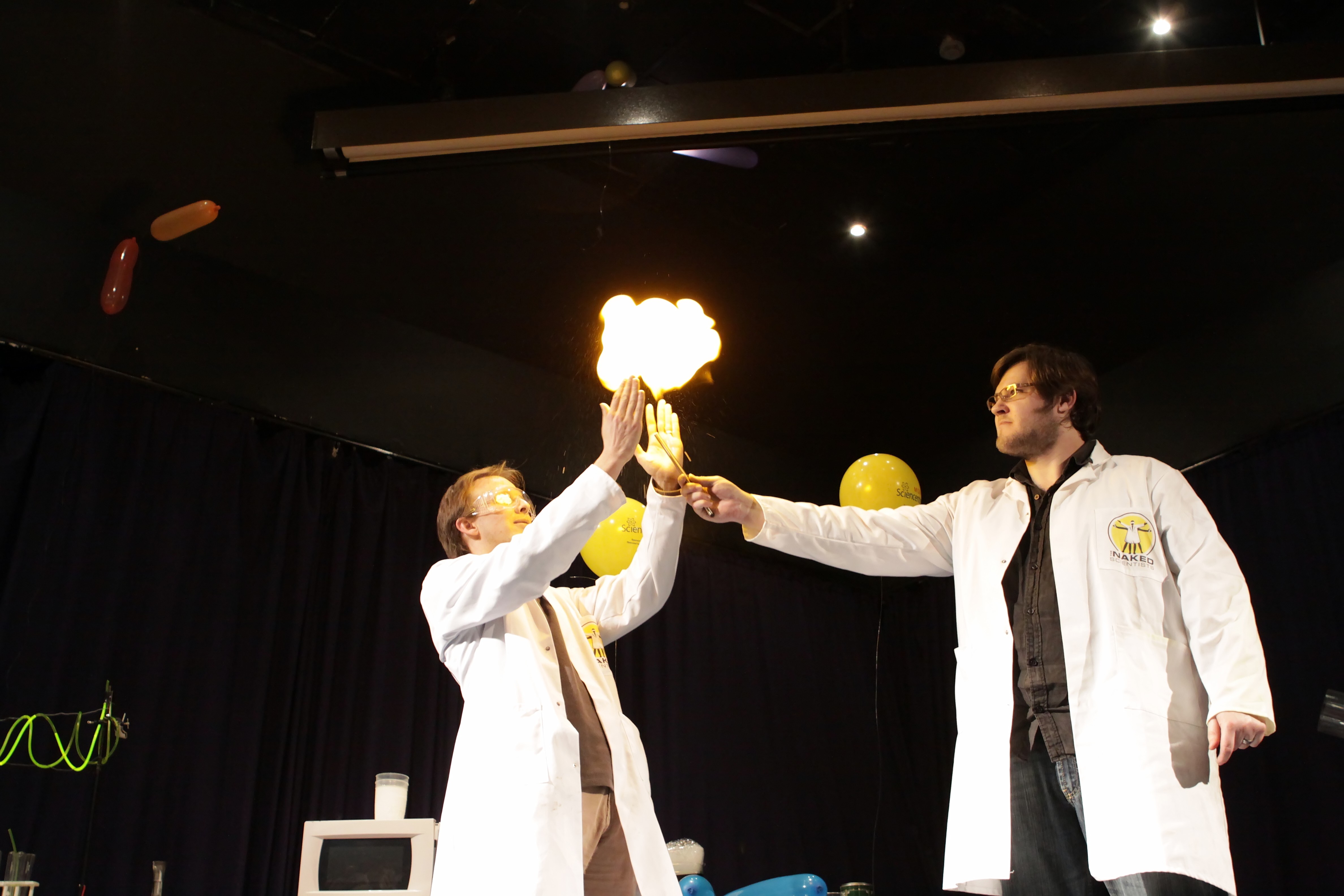

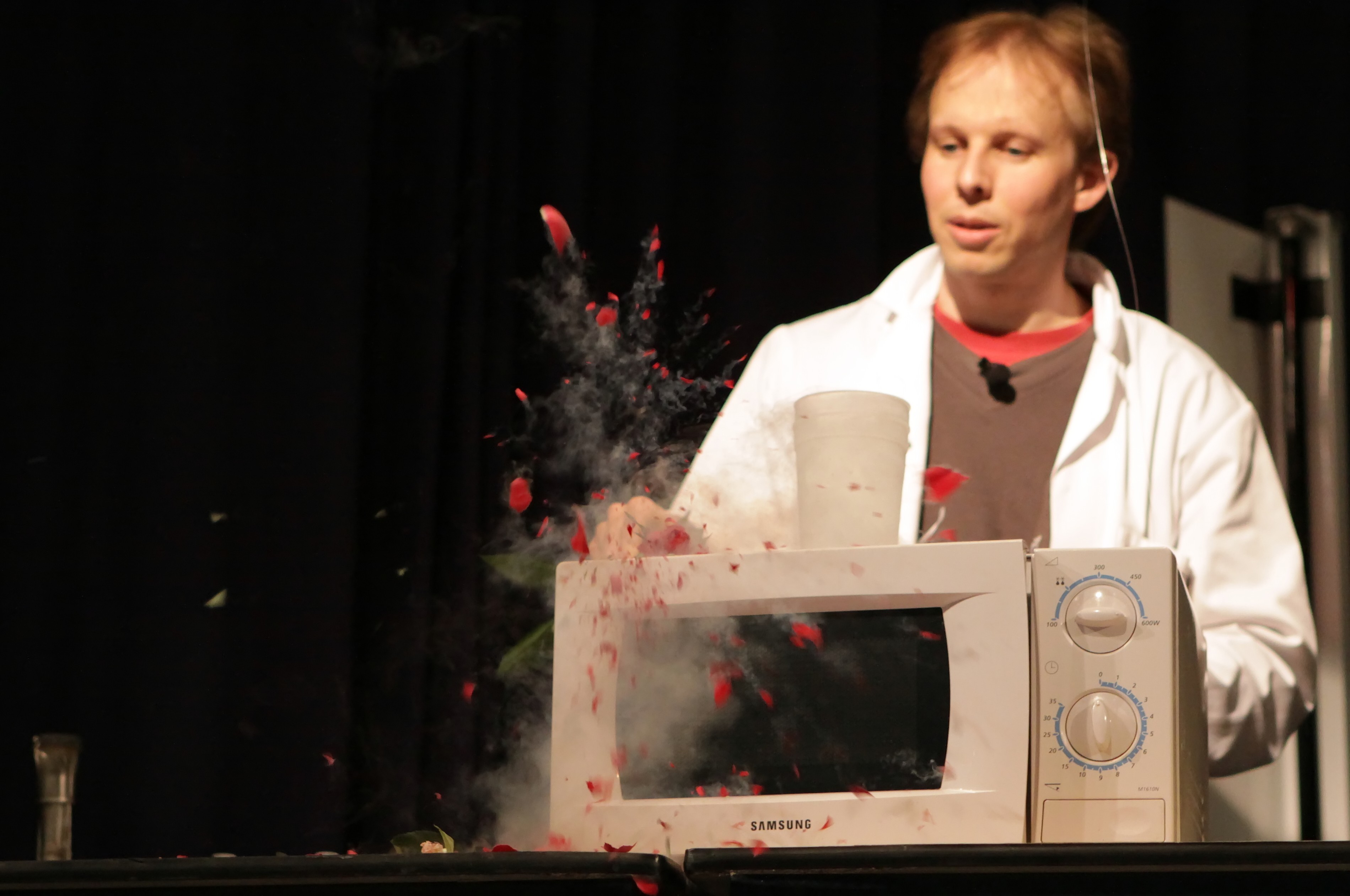

20:17 - The Crisp Packet Fireworks Show!

The Crisp Packet Fireworks Show!

with Chris and Ben

Meera - It's 1 o'clock on the day of the first Naked Scientists show and I'm here backstage.

Chris - It's 1 o'clock! Have we only got half an hour?

Ben - We have 30 minutes to get everything ready before we go onstage.

Meera - How is everybody?

Ben - Well, we've practised pretty much everything. We know what we're doing. We've had to write down the order but we do roughly know what we're doing. Everything's on the stage, laptops are all set up. I think we should be ok. Now we've just got to hope some people turn up!

Ben - Well, we've practised pretty much everything. We know what we're doing. We've had to write down the order but we do roughly know what we're doing. Everything's on the stage, laptops are all set up. I think we should be ok. Now we've just got to hope some people turn up!

Meera - I've met a lot of school kids this morning that are all expecting great things. What's your reaction to that?

Chris - Actually I went to the talk before to see what the audience were going to be like. It was absolutely packed out. This auditorium is massive. It's 900 seats out there and there's schoolkids in all of them. They seem to be an enthusiastic audience but at the same time we've not done this show before. We've not done it as a three parter with me, Dave and Ben so this is going to be really interesting to see if we can (a) remember what we're going to say and (b) what we're going to do and then ...while I get to (d) probably that these experiments work. Fingers crossed. We nearly blew someone away in the foyer earlier when we were doing a few test runs with our hydrogen. This guy appeared wide-eyed. I thought we were going to give him a heart attack and he said, 'That was really loud! Especially the second detonation.'

Meera - I see here you've got your ear defenders on Chris.

Chris - Yeah. That's so I can't hear myself.

Meera - Ben, you've got a nice running order on a clipboard there that should help things run a bit smoothly.

|

| Glowing Highlighter - as part of Crisp Packet Fireworks at the MTN Sciencentre, Cape Town © Jason Hudson - http://www.contextual.co.za/ |

Ben - It will once I've fully populated it. There's all sorts of different things that we're doing. We're doing lots of experiments with different themes. It's a case of making sure we know what the theme is at every time we nicely go from one to the other because we want people to take a lot away from this. It's not just bright lights and big loud bangs. There's quite a lot of stuff you can learn from our talk which is what we try and do all the time with things like Kitchen Science. I'd better go and set a few things up on stage and colour myself in. The very first thing I'm doing is standing in UV light with lots of highlighter pen all over my arms. You shouldn't be able to see the highlighter pen in normal light but as soon as we've switched the UV on I'll be glowing. That should be quite a good start.

Meera - That should be a nice surprise. Good luck!

Ben - Cheers!

Meera - The crisp packet fireworks show features glowing chemicals, liquid nitrogen, a tornado of fire and exploding hydrogen balloons. With over 20 experiments packed into a one hour show it's fast-paced and keeps the audience on their toes. The grand finale features Chris pouring liquid nitrogen into a large bucket of hot soapy water. This nitrogen boils and expands to around 600 times its liquid volume, creating an enormous amount of bubbles almost instantly. This plume of bubbles nearly hits the ceiling and most definitely covers Chris. For the audience this is a great way to finish.

Vincey - My name's Vincey Rada.

Meera - Have you just come out of the Naked Scientists' show?

Vincey - Yes, I have.

Meera - What did you think?

Vincey - It was a very good show. They did a lot of experiments, it was interesting and I enjoyed it immensely.

Meera - What was your favourite experiment?

Vincey - I think my favourite experiment was the last one. They had a bubble bath and then they put liquid nitrogen in the bubble bath. It all foamed up.

Meera - Made a big mess?

Vincey - Yes.

Meera - Jeremy - did you come out of the Naked Scientists' show?

Jeremy - Yes, it was very good.

Meera - What was your favourite experiment that they did?

Jeremy - The one where they fried the pickle or electrocuted the gherkin. It was like a homemade electric chair.

Meera - What happened to the gherkin?

Jeremy - It flamed up and went an orange colour.

Meera - Has this made you want to go home and try out some experiments for yourself? That are safe, of course.

Jeremy - Yeah. Yes!

Meera - Hello, what's your name?

Onilla - Onilla Chandran.

Meera - Have you just come out of the Naked Scientists' show?

Onilla - Yes. I've just seen it.

Meera - What did you think? Did you like it?

Onilla - I highly enjoyed the show.

Meera - Did it make you like science more or did you already like science anyway?

Onilla - I already had an enjoyment for science but more boosted my confidence in science.

Meera - There were a lot of experiments in there. What was your favourite experiment?

Onilla - My favourite had to be the fluorescent highlighters where they pained themselves. You could see them through the UV lighting.

Meera - What's your name?

Zis - Zis.

Meera - Did you just come out of the naked Scientists' show?

Zis - Yes, I did.

Meera - Did you enjoy it?

Zis - I did, very much.

Zis - I did, very much.

Meera - Has it made you like science more or did you like it anyway?

Zis - I did like science before I got into that and I love it more.

Meera - What was your favourite thing that they did today?

Zis - When that blue balloon

Ben - That blue balloon was filled with a mixture of two parts hydrogen to one part oxygen. When ignited they react together with explosive results. The audience certainly enjoy it and it led to the SciFest organisers awarding us the Golden Earplugs Award: a prestigious award for the loudest act at the festival.

These incredible pictures are courtesy of Jason Hudson - find him at

http://www.contextual.co.za/

|

| ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

|

|

26:15 - The Story of the Coelacanth

The Story of the Coelacanth

with Paul Skelton, South African Institute for Aquatic Biodiversity

Paul - It was a chance encounter. It occurred in December, 1938 for the first time. What happened there was there was a South African trawler coming into harbour on the day before Christmas. When it came into harbour the captain of the trawler contacted Marjorie Courtenay-Latimer at the East London Museum and she came down to the harbour. She went on deck and there was a pile of fish on deck. She shifted them about a little bit and then she said she saw this wonderful blue. She had the first specimen of the living coelacanth to be found. She saw this lovely fish, put it in a taxi, took it back and then sent a letter down to J.L.B. Smith. J.L.B. Smith was a chemistry professor at Rhodes University but a well-known ichthyologist. He recognised the sketch and thought it was a coelacanth. He announced this to a disbelieving world at that time.

Meera - Why was this finding so incredible? What was so special about this fish?

Meera - Why was this finding so incredible? What was so special about this fish?

Paul - First of all, it was very special because coelacanths were known to ichthyologists but they were only known as fossils in the fossil record. The latest or the most recent fossil was about 70 million years old. When this came out there was a gap of 70 million years between the known fossil record and this living specimen: stunning. Stunning because it was of a living lineage or great interest to ichthyology. It's got unique features that no other living fishes have.

Meera - This is a fish that would have been living at the time of the dinosaurs.

Paul - Oh yes. It goes right back to Devonian times, 400 - before the dinosaurs. It's endured the ages of the dinosaurs and everything else. The lineage has survived, not necessarily the species but the lineage.

Meera - What marks it as a unique species, this coelacanth?

Paul - there are a number of special features and these are displayed in this specimen which we have dissected to show some of these features and some of which aren't even obvious with that dissection. The fins, for example, if you look at the structure of several of the fins they are unique in having a limb. That is very unusual. In fact the structures of those limbs are predecessors in a way to tetrapod limbs. They've got the bone structure of a tetrapod.

Meera - Is this why it then has the nickname of 'fourlegs?'

Meera - Is this why it then has the nickname of 'fourlegs?'

Paul - Oh yes. Without doubt. That gave it its famous nickname of 'fourlegs.' It looks like they've got legs and not fins as other fishes.

Meera - This is a very large fish. I'd say this particular specimen is over a metre, maybe a metre and a quarter long?

Paul - Yes. This is not the largest specimen on record but it is a full-gown adult. They get pretty big, up to round-about two metres in length. That's the height of a man. They get up to 100kg in weight so they are big fishes.

Meera - With this particular specimen here you've cut out a section to show its internal organs. What's so special about the organs of this fish?

Paul - This shows a notochord. That's that tube that you see exposed in the midsection there. Instead of the bony backbone like you or I have this species has a pneumatic tube. It's like a hosepipe. It extends right from the head right to the tip of the tail. That tail form is also very unique for these fishes. You won't find another fish with a tail like that.

Meera - What makes the coelacanth extra special is that, as you say, it hasn't changed over time. Its form and its structure has remained fairly constant. Why do you think this is?

Paul - If you look at the fossil record there are fossil coelacanths that are almost identical in form to the modern coelacanth. It hasn't changed structurally very much over time. Why not? Well, the pressure's to do so probably aren't there. In other words it's probably maintained a lifestyle very similar to the one we observe in the modern day coelacanth for that long time. Although other coelacanths were found in other habitats, for example in estuaries, the body form that requires quiet waters and lives in caves, it manipulates and lives in small groups - all those features probably held over a long period of time.

Paul - If you look at the fossil record there are fossil coelacanths that are almost identical in form to the modern coelacanth. It hasn't changed structurally very much over time. Why not? Well, the pressure's to do so probably aren't there. In other words it's probably maintained a lifestyle very similar to the one we observe in the modern day coelacanth for that long time. Although other coelacanths were found in other habitats, for example in estuaries, the body form that requires quiet waters and lives in caves, it manipulates and lives in small groups - all those features probably held over a long period of time.

Meera - Where do you find this fish? Where does it live?

Paul - We now know that the coelacanth is widespread in the East African coast. They've also been found in Indonesia, about ten years ago a single specimen was reported and then a subsequent specimen was actually collected. We suspect we don't know the full story of their distribution but it's much more widespread than we believed previously.

Meera - What do you think the information we know about the coelacanth and the fact that it existed so long ago can help us understand more about in science?

Paul - There's lots it can tell you. It's a lineage of vertebrate diversity that is not represented anywhere else. That particular lineage and the features of it - anything we learn and know about it is going to assist our understanding of life on Earth, obviously. There are many features even in the embryogenesis - why have they retained a notochord? Those simple questions, all obvious questions start allowing us to ask some of the developmental and evolutionary questions. Some of the features are advanced. Behavioural studies - how do they survive, what do they feed on? What are the population dynamics? How do they communicate? They're so widespread in the Western Indian Ocean and they're not given to being strong swimming forms (in other words out in currents) how do they disperse? All these questions are going to assist us understanding life in the marine world if nowhere else.

33:21 - Protecting The Black Rhino

Protecting The Black Rhino

with Jed Bird, Addo National Elephant Reserve

Jed - I'm on a sort of voluntary basis monitoring the black rhino population for the park. I've been doing so for the last four and a half years now. Recently last year we started a research project on the rhino to try and find out a little bit more about them form a hormone point of view. We're situated in the Eastern Cape, 70km inland from Port Elizabeth (a very diverse area) that is probably one of the leaders in black rhino conservation. We sit now with over 70% of this particular subspecies of black rhino that's in the park.

Chris - Tell us about the differences between black and white rhinos.

Chris - Tell us about the differences between black and white rhinos.

Jed - There's obviously nothing to do with colour. One is no more black than the other one is white. When the Dutch settlers landed in the Cape here they named all white rhino the wyd renoster - that's the Swahili for grazing rhino. We interpreted that 'wyd' as white. We then discovered a second species called the black rhino.

Chris - Because you had a white rhino you called it black?

Jed - Exactly, yeah. The black rhino is a lot smaller, about half the size of a white rhino. It's got a pointy lip as opposed to a square lip suitable for browsing. The feed mainly on leaves and twigs and things like that.

Chris What about numbers?

Jed - that's the drastic part. White rhino numbers dropped to about 120 individuals in the tull. Through great conservation efforts in the tull their numbers have been brought back. There's about 15,000 now to date. With black rhino, black rhino number dropped to about 2000 animals and ware sitting now at about 4700.

Chris - Why are they threatened?

Jed - Poaching. Poaching and habitat destruction. To give you an idea of how the numbers dropped if you look at the period between 1970 and 1992 Africa lost 96% of all its rhino to poaching. It's seen as an aphrodisiac, the rhino horn. The main demand for it is in the Yemen tradition. When boys go from boyhood to manhood a status symbol would be to have a dagger with a handle made from rhino horn. I forget the exact dates but it was a period of 10-12 years, 22.5 tonnes of rhino horn entered Yemen which amounts to about 7000 rhino that died as a result of that. That only met 17% of the demand for rhino horn for these purposes.

Chris - What are you trying to do to stop them? I don't just mean stop the poaching but stop the decline so we don't lose another species?

Jed - The key now is to create this habitat for them. The research we're doing is trying to understand a bit more about their breeding biology and try to understand what are the most ideal circumstances for this animal to breed in and try and boost their breeding numbers. What we're doing at the moment is busy validating the use of field kits - progestogen and androgen and corticosteroid to try and monitor those hormones. How we do it is we extract it from the dung. It's not invasive: we actually don't even need to see the animal. What we do is we use camera traps. Rhino being like they are they use particular spots to defecate. There're usually scrapings that they often return to. We put a camera up at these scrapings the animal will return, do its business. We can then identify the animal, collect the dung and run it. If it's a bull we'll test its testosterone levels and its corticosteroid levels. If it's the female we'll test the progestogen. We can tell if it's pregnant. We can see if the bull's testosterone levels are high and how stressed the animal is.

Chris - We're going to head out into the bush to take a look at some of these sites and find out what it actually looks like on the ground.

Jed - We've just come out into the park. We're in an area that is one of the main waterholes used by quite a few animals or rhino in this area. We're lucky enough to stumble across some really fresh spore here. If you have a look you can see the typical three toes. That gives you an idea straight away what this is. This is black rhino, (a) I know this because there's no white rhino in that area of the park. What distinguishes this is that white rhino spore would be a lot larger than this. At the heel of the spore here white rhino would leave a much bigger indentation. You can see the black rhino is pretty flat there.

Chris - Three toes, about the size of your outstretched hand if you put your hand across it. Can you get some indication as to the size of this animal from the size of the footprint? With elephants you can draw around the whole footprint and it gives you some indication as to how tall the animal is.

Jed - yeah. There's a sort of rule of thumb if you put your hand across the spore like this. An adult animal will be slightly wider than your hand so you're looking at about 20-22 centimetres. This is a subadult animal. As you can see my hand fits quite easily over the spore. I do know there is a young male moving around in this area. He's 5.5 years old. I'm hazarding a guess this is more than likely this individual.

Chris - Would this be a good site to do the kind of monitoring exercises you're doing here in the park -setting up cameras to watch what the animals do?

Jed - This is a perfect site. As I say these game paths that lead down to the water hole obviously channel animals to this area. They'll follow these paths down to the water hole. If rhino come down here they sort of congregate in this area and move down the hill. This is a typical area where we would put the camera. It's where these paths cross or where they cross a road. That's typically a point where these rhino will either urinate or hopefully defecate. That's when we'd put up a camera trap. The animal would come past, do its business - we'll get a series of photographs, see the notches on its ears and be able to identify it and then start analysing the data for it. Let's just follow the spore for a bit and see if we come across any dung.

Chris - While we're out here in the bush in the middle of nowhere this is a wild animal park. Are there any predators here that might see a human as quite tasty?

Jed - I wouldn't say as tasty but there are a few predators.

Chris - Speak for yourself.

Chris - Speak for yourself.

Jed - There are a few predators out there. There are lion in the park, leopards and smaller carnivores called the spotted cat, things like that.

Chris - There's some pretty big bones we've just seen. What were they?

Jed - That was the remains of an eland. I don't know what killed it - more than likely a lion or hyena to bring down something that big. If you have a look here we've got some rhino dung which looks pretty much like any large herbivore dung. The secret lies here if you break it open. Black rhino is a set of browsers. They'll walk up to a bush if they pass a branch into the mouth of that prehensile lip of theirs - the way that their molars are aligned they bite things off at a 45 degree angle. If you ever question what animal this could be just break the dung open. You'll see twigs - that'll eliminate white rhino. White rhino just eat grass. Then you could be sitting with the situation - is this elephant or black rhino? Just simply look for a couple of twigs broken off at 45 degree. That tells you straight away this is black rhino.

Chris - It's pretty cunning that you can noninvasively go to the dung and measure these hormone levels. What are they telling you? Why is that important?

Jed - What we're doing here is comparing three different sections of the park. The three sections that have rhino in them which is the Addo section, Inyati section and the Darlington section. These have the same population size in each section but the variables differ from a case of elephant numbers, predation in the specific sections and tourism numbers. The hypothesis is that with a higher stress level they're not going to breed at an optimum level. We want to see basically what is the perfect scenario for these animals to live in realistically. It'd be great to put a rhino and even if no one gets to see them and they'll probably breed perfectly. In reality if you want to conserve these animals people want to see them. They want to know a bit more about them. We just want to know what levels of impact these animals can take and what levels of impact from an elephant point of view they can take.

Chris - You need people to come and see the animals, eco tourism because that brings revenue to the park, it beings revenue to the region. That means that people then respect the animals because they have a commercial value other than just for poaching. At the same time you need to make sure the animals aren't being so stressed they're not going to breed.

Jed - Exactly. It's a fine line. You've got to keep that balance like everything. As long as these animals are being seen more's going to be known about them. That's the way of conserving.

Chris - Have you got any result yet or are you still gathering the data and there's no trends emerged yet?

Jed - We've gathered quite a lot of data. Basically what we can see now is when an animal is coming into oestrus for the first time you can tell when an animal is pregnant or when she's about to give birth because the progesterone levels drop prior to birth. We can also see on bulls particularly when they're most aggressive or when they've got the highest levels of testosterone. We've found the testosterone levels increase from birth to the age of about 7-8 years old and plateau. They drop off at about 21 years old.

Chris - What about the interaction with the viewing public? Have you got any handle on that and how the stress of having people and vehicles passing nearby affects the animals?

Jed - Definitely. Just from monitoring and seeing their movements you can definitely see the trend where there's movements in the section. It's the public section where there's quite an intricate road network and there's a lot of vehicles driving around. You can see the time of day these animals are moving and the areas that these animals are moving. They do tend to avoid roads and avoid vehicles and people.

Chris - Is it something they could get used to?

Jed - Most definitely. That's what I was getting at. You can't expect to put animals into an area that they never get seen. Realistically you have to monitor them anyway. If you don't see people or vehicles for six months, a year, and then all of a sudden they do then their stress levels are going to rocket. If they get accustomed to it to a certain degree it balances. To a certain degree they won't get as stressed when they do hear a vehicle or do smell people.

44:39 - Tackling Tuberculosis

Tackling Tuberculosis

with Valerie Corfield, University of Stellenbosch

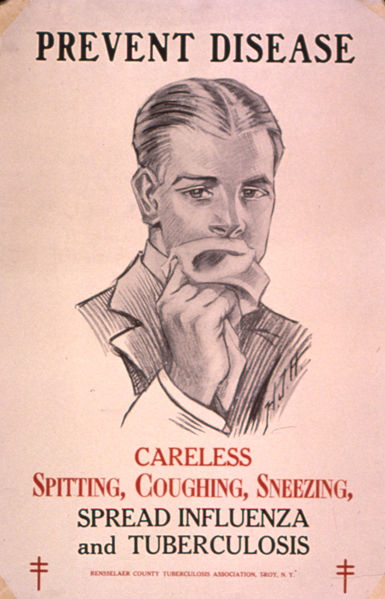

Valerie - It's a rather mean, sneaky disease. It's a bug, it's a bacterium. TB likes to get inside the body. Bodies are nice and warm, a comfortable sort of place. It likes to hang out there. It doesn't really want to do any damage but the trouble is while it's hanging out there is does cause some damage.

Meera - What damage does it do to your body?

Meera - What damage does it do to your body?

Valerie - Well, it needs to live. Because it's a nice warm comfortable place it tends to divide and divide and make more of itself. In doing that it needs some food and it needs space. It's gradually pushing itself around in the lungs, pushing lung tissue out of the way - actually making holes in the lung.

Meera - What bacteria is it that causes this?

Valerie - We're talking about a bacterium called mycobacterium tuberculosis - MTB for short.

Meera - What are the symptoms once it kicks in?

Valerie - Coughing's the main thing. That's what people notice. If one's coughed for more than two weeks one should actually go to a clinic and get tested for it. If it gets as far as coughing and spitting up blood that's very bad news. At the same time the patient will feel tired. They might have some chest pain, night sweats maybe loss of appetite, fever. Any of those symptoms and those symptoms in combination but coughing is the real one that will tell you there's something wrong with your lungs.

Meera - how do people catch it?

Valerie - They catch it mostly because other people who are infected cough. When we cough we spray out a tremendous amount of little droplets. We can't even see them. The reason we have this big face here - Mr Coughit. He's a model and when he coughs he sprays these fine droplets of water out into the air. If he was a person who had TB and he had TB in his lungs when he sprayed this liquid out into the air in a big cough he'd also be spraying out lots of the MTB, the germ and then other people may breathe that in, get into their lungs, settle down in their lungs and start growing.

Meera - Can you show me Mr Coughit in action then?

Meera - Can you show me Mr Coughit in action then?

Valerie - Here he goes..

Meera - Nice sound effects there. Essentially Mr Coughit is actually a face mask with a water spray bottle attached under him. This mist is going quite far actually. It's going about a metre away.

Valerie - I believe that really one's coughing goes farther than that because our lungs are more powerful than this spray bottle. Really powerful cough; one could be sending it 2 metres or more through the air. People for a long way around could be infected as they're innocently going about their business.

Meera - How serious a disease is it? How badly can it affect your body and also is there a treatment for it?

Valerie - It depends on the person and how susceptible they are. One third of people in the world have got MTB in their body. Usually it's been encapsulated, it's in a little prison in their body and it's sleeping. It's dormant/latent. It's not doing any harm. Sometimes a person may be down at that particular time, their immune system is not working so well, they could be depressed, they could be under stress, they could be malnourished. In South Africa one of the problems is they may be infected with HIV. They may have AIDS which will depress their immune system. Under those circumstances the MTB bug can get a hold quicker and het going quicker. It's not only found in the lungs. That's where we see the symptoms initially and that's where the first point of treatment is but it can also spread. It can be a bone disease. It can go to the lining of the brain. It can affect the heart. It can be in the lymph nodes. When it's been diagnosed the treatment is antibiotics but unlike other antibiotics, say for a sore throat the TB bug lives for a long time in the body. It's very hard to get those antibiotics right in there. The antibiotics have to be taken for six months.

Meera - That's a long time.

Valerie - Yeah that's a long time and that's what causes one of the problems. A person will begin to feel better from the effect of the TB, their breathing will be easier, they'll not have the night sweats. They may begin to get their appetite back, start eating, feel a lot better. They'll think alright, it's gone - I'll not take my medication any more.

Meera - How prevalent is it?

Valerie - In Europe in the 19th century it was quite a problem during the industrial revolution. With increasing knowledge about the bug, antibiotics, better sanitation, better living spaces the disease was conquered. Right now it's spreading again. It's actually a problem throughout the world.

Meera - There is a vaccination available to protect people against TB.

Valerie - yeah, there's BCG and BCGs usually given to kids quite early on in their lives. In places like South Africa it's not working very well. It's a very old vaccination. Nothing new has been developed and I think the biggest problem now is no new antibiotics have been developed, the TB bug is acquiring a resistance.

Meera - How big a problem is it here in South Africa?

Valerie - We've got a big problem in South Africa. There's a lack of understanding with what's going on in TB. People stop taking their medication. They stop taking it too early. There's still TB in their system and those TB bugs may have acquired little changes, they're a type of mutant. They become resistant to the antibiotics. They become resistant to the first line antibiotics. Once they've got resistant to more than two antibiotics they're called multidrug resistant. Then a new lot of antibiotics have to be brought in. The trouble is now multidrug resistant TB may acquire another mutation which makes them extremely drug resistant TB. Presently there are no antibiotics that effectively kill XTB.

- Previous An Odyssey to the Red Planet

- Next SciFest Africa

Comments

Add a comment