We hear how researchers have caught swine flu in the act of mutating in this NewsFlash, as well as discovering how migrating humans carried parasites out of Africa, a new gene therapy for HIV and why females are more likely to suffer the effects of stress. Plus, bomb proof curtains that expand when they're stretched!

In this episode

00:21 - Swine flu caught in the act of mutating

Swine flu caught in the act of mutating

Scientists monitoring pigs in Hong Kong have spotted human H1N1 swine flu rearranging its genes.

Writing in Science this week, Hong Kong University researcher Dhanasekaran Vijaykrishna and his colleagues describe how, by monitoring samples from pigs sent for slaughter, in January 2010 they picked up a new strain of swine flu with unknown pandemic potential. Owing to the perceived threat that pigs pose by acting as molecular mixing vessels permitting swine, bird and human flu strains to swap genetic material, the team have been monitoring the Hong Kong abbatoir for over ten years.

Between January 2009 and February 2010 they picked up 32 cases of flu amongst pigs, including classical swine flu strains and (since October 2009) cases of the H1N1 swine flu that caused the human pandemic.

Between January 2009 and February 2010 they picked up 32 cases of flu amongst pigs, including classical swine flu strains and (since October 2009) cases of the H1N1 swine flu that caused the human pandemic.

But the virus detected in January was different. It contained the core molecular workings of a circulating strain of swine flu but also had acquired the haemagglutinin (H) surface coat of the human H1N1 pandemic strain. This shows that the human pandemic strain, when it enters pigs, can clearly "reassort" with other pig flu viruses, potentially generating novel pandemic strains that might have enhanced virulence amongst humans.

Tests carried out by the researchers showed that the new strain could transmit readily between the pigs, indicating that it was fully infectious, although it tended to produce a mild illness.

Nevertheless, this observation should serve as a warning, say the researchers, that more widespread surveillance of pigs is crucial in order to help us to predict and mitigate potential future threats to public health.

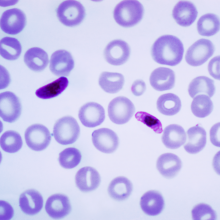

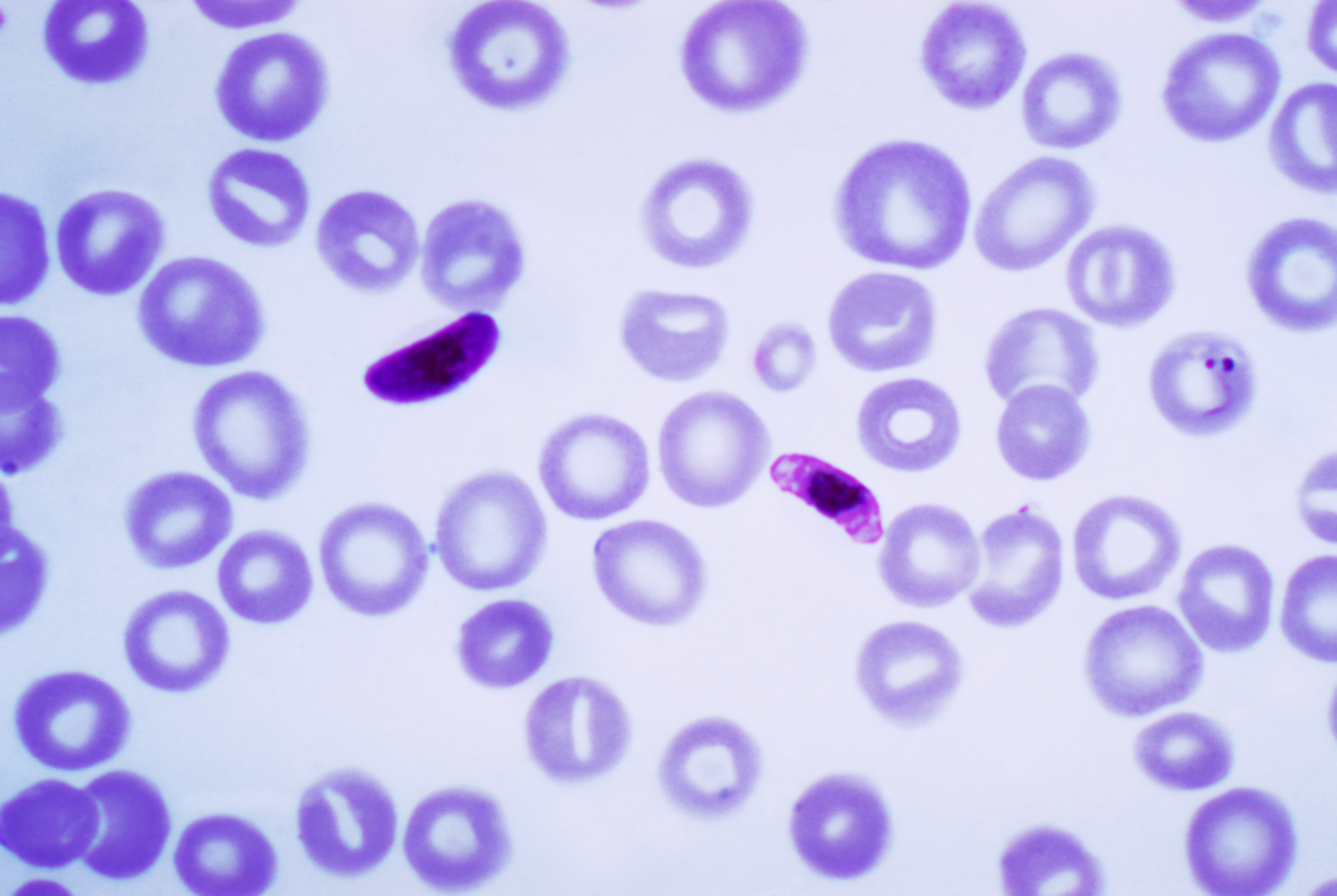

02:07 - Humans carried Plasmodium falciparum with them out of Africa

Humans carried Plasmodium falciparum with them out of Africa

This week, a team of scientists have shown that one of the deadliest strains of malaria travelled with early humans as they left Africa and colonised Asia.The current understanding is that modern humans evolved in the Afar region of Ethiopia. About 55 thousand years ago, they began to migrate out of Africa to colonise what is now Europe and Asia.

The paper, published in Current Biology, describes that there is a decline in the genetic diversity of the populations of Plasmodium falciparum as you move further away from sub-Saharan Africa. The team collected blood from individuals infected with falciparum from countries in Africa to South East Asia and South America. Because Plasmodium falciparum only infects humans, it can only have been transported out of Africa via humans. The team compared the genetic diversity of the parasite with the timing of migrations out of Africa.

The paper, published in Current Biology, describes that there is a decline in the genetic diversity of the populations of Plasmodium falciparum as you move further away from sub-Saharan Africa. The team collected blood from individuals infected with falciparum from countries in Africa to South East Asia and South America. Because Plasmodium falciparum only infects humans, it can only have been transported out of Africa via humans. The team compared the genetic diversity of the parasite with the timing of migrations out of Africa.

It's already well documented that the genetic diversity of human populations decreases as you move further away from sub-Saharan Africa, because people have simply been there for less time and there has been less time for new mutations to arise. The team found that the genetic diversity of the parasite decreased with distance in exactly the same way, and the age estimates fitted with the parasite accompanying the migrating early humans, with the exception of South America, where the results pointed to a much more recent invasion of the parasite - probably to do with the slave trade.

The genetic diversity of the malaria parasite plays a key role in how dangerous it is, so knowing more about the diversity can help us to find better ways to fight it, which given that falciparum is the most dangerous strain of malaria, is a very good thing.

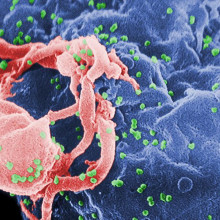

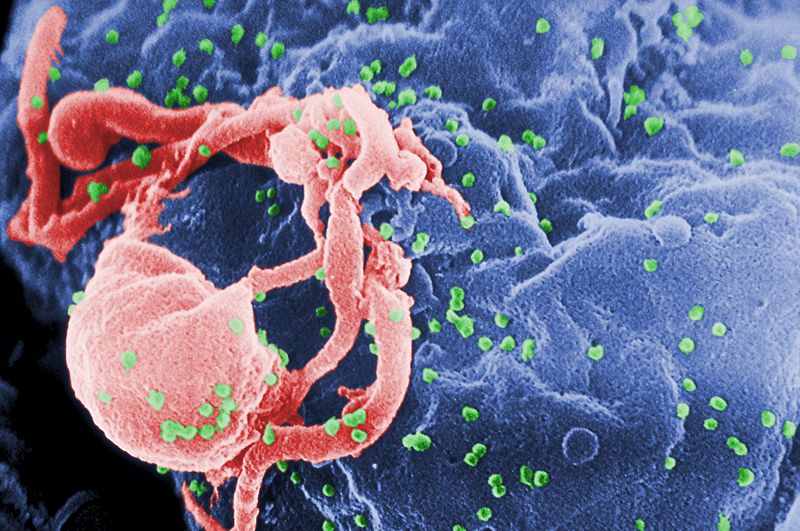

04:42 - Gene therapy aids HIV treament

Gene therapy aids HIV treament

Scientists have found a way to use gene therapy to combat HIV infection.

Although drug therapy has revolutionised the treatment of HIV, it is not curative and inevitably patients still eventually succumb to drug-resistant forms of the virus, treatment-related side effects or cancers such as lymphomas, which occur much more commonly amongst HIV-infected individuals. Part of the reason why HIV is so hard to treat is that the virus lurks inside the human genome, inserting covert copies of its genetic material into the host DNA where it sits out of reach of the effects of drugs or the immune system.

Consequently, in recent years, scientists have been attempting to develop "genetic medicines" that can target this hidden form of the virus. Previous attempts to carry out "gene therapies" in humans, for a range of different diseases, have produced mixed results and are often hard to justify on ethical grounds.

Consequently, in recent years, scientists have been attempting to develop "genetic medicines" that can target this hidden form of the virus. Previous attempts to carry out "gene therapies" in humans, for a range of different diseases, have produced mixed results and are often hard to justify on ethical grounds.

But now a team based in California have provided encouraging evidence that such a strategy might work. Writing in the journal Science Translation Medicine, City of Hope scientist David DiGiusto and his colleagues explain how they have safely and stably genetically modified the immune cells of seven HIV patients to make them resistant to HIV.

The team first collected non-HIV infected blood stem cells from the patients, who were undergoing treatment for lymphoma, a blood cell cancer that occurs more than 100 times more commonly in patients with HIV. Working in the culture dish, the researchers then used a disabled virus to add to the cells several genes that interfere with the growth of HIV.

The cells were then maintained in culture for a further period of time to check that they were safe before they were reinfused back into the patients where they took up residence in the bone marrow and began to produce new blood cells.

Checks on the patients' blood confirmed the presence of cells carrying the anti-HIV genes two years later, when the study ended. This shows that techniques like this can be used safely to protect immune cells from HIV infection.

Next, a much larger study, in which higher counts of modified cells are administered, will be needed to determine whether this technique can aid the elimination of HIV from the body.

07:28 - The molecular reason females are more likely to suffer the effects of stress

The molecular reason females are more likely to suffer the effects of stress

Researchers in Philadelphia have found that there is a difference at the molecular level between how male and female brains deal with a particular stress hormone, which could explain why women are more prone to stress or anxiety related illnesses like post traumatic stress disorder and depression.

The study, published in the journal Molecular Psychiatry by Debra Bangasser and her colleagues, compared the brains of male and female rats in stressed and unstressed situations. They measured the activity in the brain cells using electrodes and also took samples of brain tissue to look for specific proteins.

The study, published in the journal Molecular Psychiatry by Debra Bangasser and her colleagues, compared the brains of male and female rats in stressed and unstressed situations. They measured the activity in the brain cells using electrodes and also took samples of brain tissue to look for specific proteins.

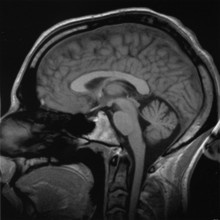

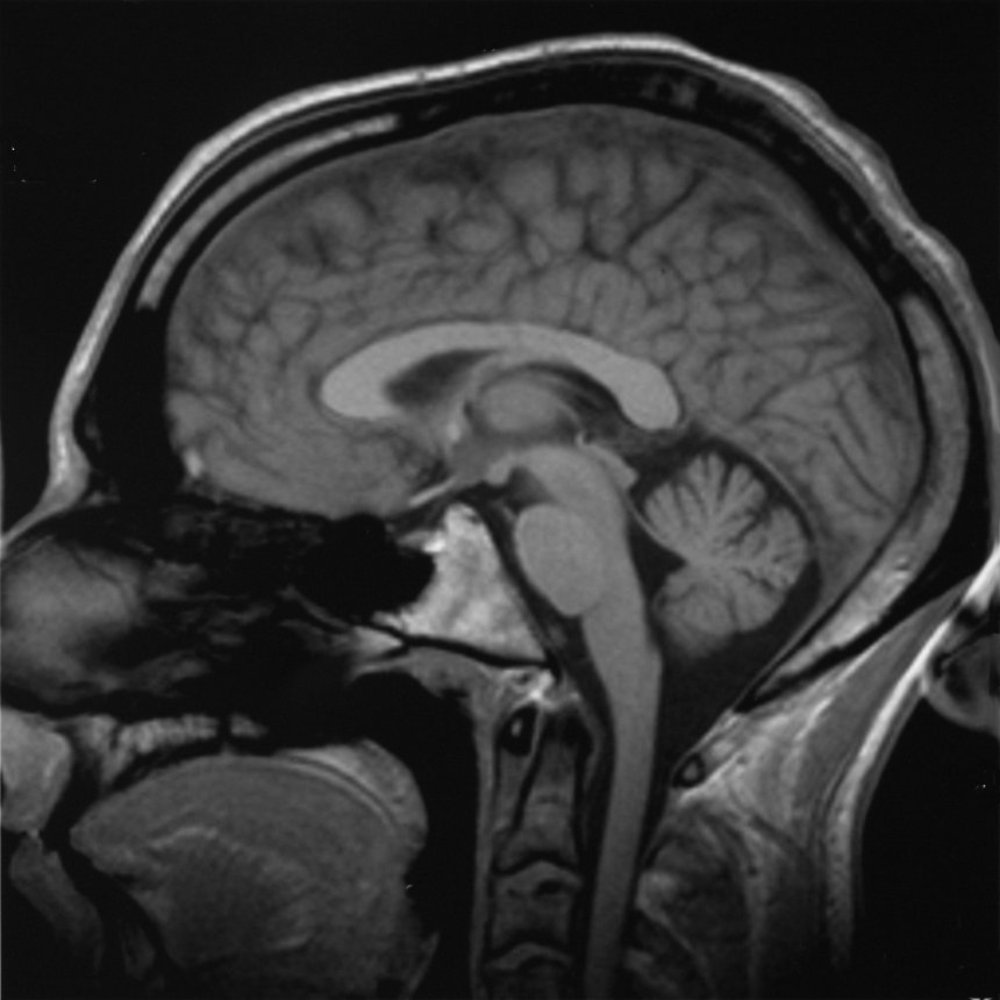

The stress hormone they were looking at is called Corticotropic-releasing factor or CRF, and it's produced in a region of the brain called the hypothalamus, and it plays a key role in stress, along with hormones from an area in the brainstem called the locus ceruleus. Activation of the locus ceruleus and the hypothalamus by a stressful stimulus or situation leads to the production of other hormones, like adrenaline, that can lead to many of the symptoms of stress disorders - like sleeplessness or inability to concentrate.

The team found that the female rats were much more sensitive to the CRF than the male rats, meaning that they would be more likely to react to a stressful situation than a male rat would be. But they were also less able to deal with high levels of CRF - the males could lock it away in little sacs in the brain cells called vesicle, and this allowed them to adapt to the higher levels, but the females couldn't adapt and would continuously show the stressed response.

So what does this mean in the wider context? Well, this is only a study in rats - it may not translate directly to humans, but it does offer a pretty good model. What's interesting is that because we now know that the CRF receptors in male and female brains differ, and we know HOW they respond to CRF, this could open up new avenues of research for drugs to treat things like depression and post-traumatic stress disorder. And it may mean that we need to look at treating males and females with these illnesses in different ways.

09:59 - Expanding blast-proof curtain will reduce impact of bomb explosions

Expanding blast-proof curtain will reduce impact of bomb explosions

A new type of blast-proof curtain that gets thicker, not thinner, when stretched is being developed to provide better protection from the effects of bomb explosions.

The Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC) project is being led by the University of Exeter in collaboration with their spin-out company Auxetix Ltd and three other partners.

The new curtain is designed to remain intact and capture debris such as flying glass when windows are blown in. Debris of this kind can cause severe, sometimes life-threatening injuries to people working or living in buildings within a blast zone.

The curtain is primarily designed to be fixed over the inside of windows in buildings that are potential terrorist targets, such as Government and high-profile commercial properties. Potential uses could also include protecting building occupants from the effects of severe weather events such as typhoons and hurricanes.

| Expanding blast-proof curtain will reduce impact of bomb explosions |

Blast curtains currently in use essentially consist of thick net-curtain fabric and work in conjunction with an anti-shatter film applied to the window to prevent fragments of glass from tearing the material. The new curtain aims to remove the need for anti-shatter films by using stronger, more resilient fibres woven into a carefully controlled textile structure.

The secret lies in the yarn the curtain is made from. A stretchy fibre provides the core of the yarn and a stiffer fibre is then wound around it. When the stiffer fibre is put under strain, it straightens. This causes the stretchy fibre to bulge out sideways, effectively increasing the yarn's diameter. Scientifically speaking, the yarn is an 'auxetic' material - one that gets thicker when stretched.

The research team has identified a whole range of widely available, tough fibres that can be used in the yarn. Producing the yarn and turning it into a textile are also completely conventional processes.

The extent of the auxetic effect is determined by the precise angle at which the second fibre is wound around the first fibre, and also by the two fibres' relative stiffness and diameters. Altering these parameters enables the yarn's performance to be fine-tuned for specific applications (e.g. to withstand different levels of blast). The project team have focused considerable effort in this area.

Another key feature of the new curtain is that, when stretched, small pores open up in it. Although too tiny for flying debris to penetrate, these pores are designed to let through some of an explosion's shock wave. This reduces the force the curtain is subjected to and so helps ensure it doesn't rip.

At just 1-2mm thick, the new type of curtain can also be designed to let in a reasonable amount of natural light. It is currently being tested in situations similar to car bomb explosions.

"In the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing, glass accounted for nearly two thirds of all eye and head injuries," says Professor Ken Evans, who is leading the project. "The blast curtain we're working on, which will be capable of dispersing the shock from an explosion extremely effectively, will be backed up by robust scientific understanding vital to ensuring it really can block flying debris and achieve widespread use."

Testing at a Government-approved facility has already commenced. Following rigorous certification procedures, the new curtain could be on the market within three to five years.

The fabric could also be used in other areas such as:

- The manufacture of smart, self healing auxetic bandages. Wounds that swell would put the bandage under tension opening up pores that are impregnated with an antibiotic which would then be released. - Dental floss that expands when you pull it, to fill in gaps to make cleaning more effective for teeth. - Civil engineering for the reinforcement of soils and for storm and flood mitigation.

Related Content

- Previous Can dogs watch TV?

- Next Seriously Small Structures

Comments

Add a comment