Dishing the Dirt on our Soils

This month, the United Nations published its much-anticipated report on the state of the world's soils and the results are not good. We'll be asking why, and taking a down-to-earth look at the consequences to see what we can do to reverse the trend. Plus in the news: why life drawing improves self-esteem; how the asteroid Ceres might be an invader from outer space; and the looming antibiotic apocalypse...

In this episode

01:00 - E-cigs could give you lung disease

E-cigs could give you lung disease

with Professor Joseph Allen, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health

The e-cigarette has blazed onto the scene recently, and it's become a big hit. They work by using a heating element to boil or vapourise a nicotine-rich mixture, that's then inhaled. An added facet is that there are literally thousands of flavours, which are made by adding scent chemicals to the mixture. Why is it though, Harvard's Joe Allen is wondering, that some of these flavour chemicals are turning up in e-cigarettes but have already been linked to serious lung diseases? Chris Smith reports...

Joe - For over a decade we've known about severe lung disease associated with inhaling flavouring chemicals because of workers in the popcorn packaging industry, many of whom develop severe and irreversible lung disease after inhaling these flavouring chemicals.

So our interest in this topic came from knowing this history of occupational disease for workers in the popcorn industry and then learning that there were over 7,000 flavours of e-cigarettes available to consumers. And we thought, and it turns out correctly, that these flavoured e-cigarettes would have a lot of the same chemicals that were of concern from the workers over ten years ago.

Chris - Tell us a bit about those workers and how that particular story came to light in the first place and what went wrong for them.

Joe - Sure. It was about in May of 2000 in the United States, 8 workers who worked at a microwave popcorn processing plant reported to have a severe and irreversible lung disease called bronchiolitis obliterans. It was investigated and determined that this was due to inhaling flavouring chemicals in their workplace.

So they would mix up butter flavour for the microwave popcorn product and then they would inhale the heated flavouring chemicals. The disease became known as popcorn lung because this is where it was first discovered in these workers, and what you have is virtually the same thing happening with flavoured e-cigarettes. You have a heating element heating the flavouring chemicals, and the consumer inhaling the chemicals.

Chris - And more critically, are they the same chemicals that you would find in a popcorn factory?

Joe - We found at least one in 92% of the flavoured e-cigarettes we looked at. IN particular, one of the chemicals that got the most attention, called diacetyl and we detected diacetyl in over 75% of the flavoured e-cigarettes we tested, and this is the chemical that in the United States the investigating agency said "it's highly likely that diacetyl contributed to the occurrence of fixed obstructive lung disease, also known as bronchiolitis obliterans, also known as popcorn lung."

Chris - Now tell us how you did this study first of all and then we can look a bit at what these chemicals are doing in these e-cigarettes, if they've already got this track record.

Joe - Sure. So, our study is very is a very simple design; we tested 51 flavouring chemicals - remember there are over 7,000 available - and we set up in my lab a system to mimic smoking or inhalation. So we pull out the chemical, just like a user would, and then we capture it on a sampling device and we analyse it according to standardised methods to look at three different flavouring chemicals so, diacetyl, acyteon and 2,3-pentanedione.

Chris - What do they smell like?

Joe - Well, this is what's interesting about the flavouring chemical issue is that it first started, we first became aware of this in the popcorn workers and it was butter flavour, but these flavourings are not limited to just butter. In fact, diacetyl is used in wide range of flavourings like caramel, butterscotch, pina colada; all sorts of fruit flavours, banana, apple, grapes, strawberry. So these flavouring chemicals are widely used to flavour a lot of the food products we consume, and actually in our study we found diacetyl and other flavourings in flavoured e-cigarettes that we deem are appealing to children like cupcake and cotton candy flavour e-cigarettes.

Chris - I mean that's a whole different ball game isn't it whether or not this acts as a gateway into smoking behaviour. But when you inhale these flavours from an e-cigarette, I think one critical question is, if you are going to link this to the same sort of damage that the popcorn workers got, is there evidence that what's coming out of the vaporiser in an e-cigarette is going to be particles, which are the same sort of size, the same chemical characteristic, as those popcorn workers would have been breathing in in the factory?

Joe - Right. So this is one of the follow-up questions that we're starting to look at and I know others are, but it's the characterisation of these at a bit finer scale. So we don't know much at all right now about the hazard associated with these flavoured e-cigarettes and that was one of our goals of our study, is to be sure that when we start talking about e-cigarettes and safety and risk, is that flavouring chemicals are part of that conversation.

Chris - To be clear here, you're not saying these chemicals cause this lung disease, but what you are saying is there's very strong evidence from other situations that there is a strong association between exposure to them and getting lung disease. Therefore, it's reasonable to be prudent and say there could be a risk here, we need to do something about this.

Chris - That's exactly right Chris. So this wasn't a study of a health effect, it's simply designed to show that we have the presence of these flavouring chemicals that didn't just cause minor diseases, they caused severe and irreversible lung disease in workers. We don't have the same kind of warnings or knowledge reaching consumers of flavoured e-cigarettes. Many of these consumers are children, and many of these flavoured eCigarettes that we've shown in our study, we feel, are even marketed towards kids.

Chris - So what would you like to see change?

Joe - Well I think at a minimum we should be regulating e-cigarettes as carefully as we regulate cigarettes.

06:34 - Body concious? Life drawing could help

Body concious? Life drawing could help

with Professor Viren Swami, Anglia Ruskin University

90% of us have experienced moments of low body confidence at some point; and  these feelings are linked with the development of depression, anxiety and eating disorders. One way to boost body image is by participating in physical activities, such as dance and martial arts. But, for the more artistically-inclined, new research has shown that attending life drawing classes has similar benefits. Viren Swami, from Anglia Ruskin University, sketched out the findings for Felicity Bedford...

these feelings are linked with the development of depression, anxiety and eating disorders. One way to boost body image is by participating in physical activities, such as dance and martial arts. But, for the more artistically-inclined, new research has shown that attending life drawing classes has similar benefits. Viren Swami, from Anglia Ruskin University, sketched out the findings for Felicity Bedford...

Viren - We had two studies; in the first study we look at attendance at life drawing sessions and the association with women's and men's body image, and we found that greater attendance at these life drawing sessions was associated with a higher body appreciation or positive body image among both women and men.

In the second half our study, we followed a group of women who had never attend life drawing classes before, and we measured their state body image, their current feelings about their body image, both before and after the class, and we found that attending the life drawing class for about 2½ hours had as significant effect on their body image. They felt better about their body image immediately after attending the class.

Felicity - That's great news for anybody considering going to life drawing classes, that you can have a fairly immediate impact upon attending just a few classes.

Viren - Exactly, so we think that the effect is both short term, but also is you continuously attend a life drawing classes, it seems to have a long term effect as well.

Felicity - How did you measure people's feelings about their bodies?

Viren - We measured three different types of body image, both women and men. We measured social physique anxiety; this is how anxious they feel about showing their bodies in public. We measured body appreciation, which is a measure of positive body image, and we measured in women's drive for thinness, this is how much they feel a drive to be thin, and in men we measured the drive for muscularity, which is a drive to feel muscular.

Felicity - You were looking at the attitudes of people attending the classes. How might drawing somebody else naked, make you feel better about your own body?

Viren - Well I think it's about embodiment. So a theory in body image research is that any activity that promotes embodiment will result in a more positive body image, so embodiment is any activity that promotes greater respect for your body or greater feelings of love and openness towards your body.

Typically embodiment is looked at in terms of actually doing something so, for example, you might actually do dance rather than just watching dance, but life drawing might be one activity where you can experience embodiment vicariously. In life drawing sessions, in particular, you're not just looking at another body, you're also to experiment with that body in terms of reproducing it in a form of art.

The other thing that life drawing sessions might do is that they might provide a safe space in which to explore your own feelings about your own body in relation to other people, or just in relation to yourself.

Felicity - What about if the models are really attractive? Could this have the opposite effect?

Viren - It's possible but I think one of the things about life drawing sessions is that you are exposed to a whole range of different types of bodies; it's not just attractive people who are life models.

I think given the nature of life drawing, I think even if the model was particularly attractive, the function of seeing that body and experimenting with that body in an artistic sense would probably have the same effect. But over the course of a period, say if you went to life drawing classes say for a year, you'd be exposed to a whole range of different bodies - some that you might find attractive, some that you might not find attractive - but it's that process of seeing those bodies and absorbing what those different mean, I think that is the most important.

Felicity - Could it be any drawing, not just life drawing, that's causing this improvement in your body image?

Viren - I think that's an interesting question. I think it is something about life drawing that promotes embodiment. I think if you can find a different art form that has the same effect in terms of embodiment, you might find the same effect. I don't think you would find the same effect if you were just drawing a tree, for example.

Felicity - But generally should we be exposed to more nudity, whether it's our own bodies or other people's?

Viren - I think there are different forms of nudity. You have nudity in everyday life when you see your partner or when you see yourself, there's nudity in pornography, there's all sorts of nudity. I don't think it's just being exposed to nudity that matters; I think it's the process of engaging with nudity and exploring what that nudity means, either in an aesthetic sense or in relation to your own self; that's probably the key point here.

11:25 - Do Dock leaves stop stinging nettle stings?

Do Dock leaves stop stinging nettle stings?

with Kat Arney, The Naked Scientists

Kat Arney continues her myth busting science...

Kat - As a child I would often be dragged out into the local forest to walk the dogs. And, inevitably, I'd end up blundering into some stinging nettles. As soon as I got stung, my mum would delve into the undergrowth in search of a dock leaf to rub on the reddening bumps coming up on my pale legs. But does this actually kill the sting?

Before we find out, let's take a step back and see how nettles actually cause their stings. Their leaves are covered in a multitude of tiny hollow needle-like hairs made of silica - the same stuff that glass is made of. When someone like me brushes up against a plant, the tips of these fragile hairs break off, piercing the skin and injecting a cocktail of nasty chemicals.

One of these if formic acid, which is also found in ant bites. Getting concentrated formic acid on the skin can cause severe irritation, pain and blistering, so it was originally thought to be the major culprit responsible for the pain and misery of nettle stings. But it turns out that the levels of formic acid in the delicate hairs are too low to cause this kind of reaction. There are other acids in the stings too - such as oxalic acid and tartaric acid, found in other types of plants. For example, rhubarb leaves are a potent source of oxalic acid, which can be toxic in high doses. but, like formic acid, they're present at relatively low doses.

So what else is in there that could be responsible for the pain and misery of a nettle sting? The other prime candidates are three chemicals known as histamine, acetylcholine and serotonin, which are all naturally produced in the body. To take a look at each of them in turn, serotonin is produced by nerve cells, and is usually associated with transmitting pleasurable sensations by signalling between nerve cells. But when injected by a nettle leaf, it has much more painful results as it irritates the skin. next is acetylcholine, another chemical that usually transmits signals between nerve cells. Again, when injected directly into the skin by a nettle's barbs, the sensation is far from pleasant.

Perhaps the major culprit is histamine, responsible for triggering pain and inflammation, as well as allergic reactions. That's why people take anti-histamines for allergy-related symptoms, such as skin rashes, wheezing and snuffling. So this is probably one of the prime reasons that nettle stings quickly redden, itch and swell - and also suggests that antihistamine cream might work to relieve the pain. But the skin reaction is probably not just down to a single molecule, but the effects of all the nasty things mixed together, so it's a complex issue.

Now on to the main question - does rubbing a dock leaf on a nettle sting make it better? Sadly for my childhood knees, the answer is no. There have been various claims that the sap in the soft, leafy plant is alkaline, and helps to neutralise the formic acid and other acids in the nettle sting. But the acids are only a small part of the problem, and dock leaves aren't even actually alkaline. So that's definitely not true. There are other claims that they contain natural antihistamines, but there's no evidence to prove that's real either. In fact, it's more likely that dock leaves are just a placebo - creating a distraction from the pain of the sting through the rubbing action of a cool leave on the sore red bumps.

So while my mum may have had the best of intentions with her insistence about searching for dock leaves for my clumsily nettle-stung legs, and it was probably as good as kissing it better, it would have been more effective if she'd had some antihistamines in her handbag...

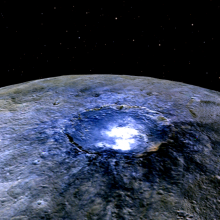

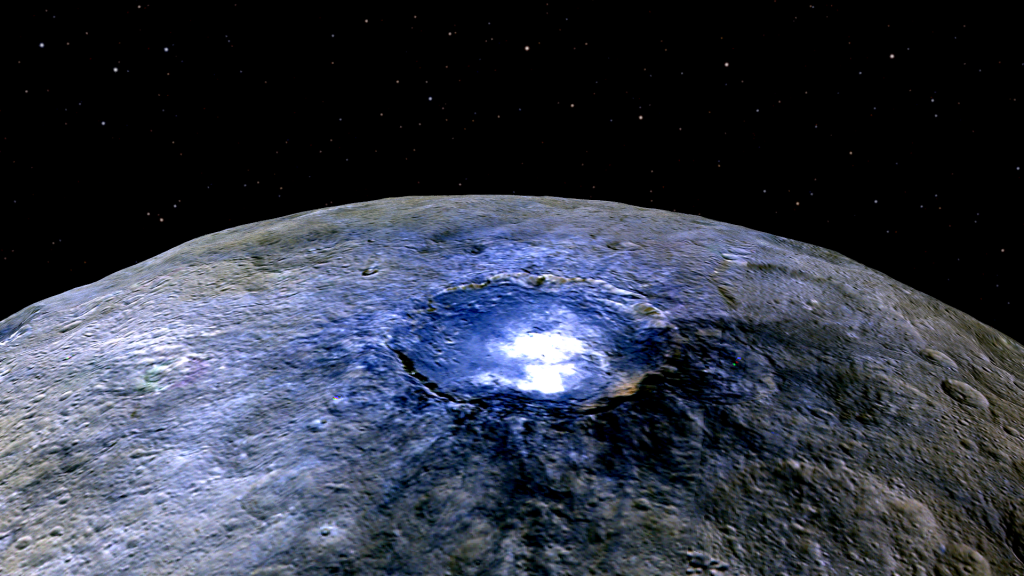

15:36 - Why Ceres might be an invader from space

Why Ceres might be an invader from space

with Professor David Rothery, Open University

What's black with white spots and half made of water? The rather surprising  answer is the solar system's largest asteroid, Ceres, scientists had thought that this spherical body, which measures about 1000km across and orbits out beyond Mars, was made of rocky rubble left over when the planets finished forming. Now, closer inspection by NASA's "Dawn" probe, which is currently orbiting Ceres, has shown that the dark black surface of the asteroid is punctuated with bright white spots, which appear to be made of salts, ammonia and water ice. But finding these means that Ceres might not originally be from the asteroid belt at all but is instead a deep space interloper! Chris Smith spoke to David Rothery about the finding...

answer is the solar system's largest asteroid, Ceres, scientists had thought that this spherical body, which measures about 1000km across and orbits out beyond Mars, was made of rocky rubble left over when the planets finished forming. Now, closer inspection by NASA's "Dawn" probe, which is currently orbiting Ceres, has shown that the dark black surface of the asteroid is punctuated with bright white spots, which appear to be made of salts, ammonia and water ice. But finding these means that Ceres might not originally be from the asteroid belt at all but is instead a deep space interloper! Chris Smith spoke to David Rothery about the finding...

David - Ceres is the largest asteroid; it's the largest body in the asteroid belt; it was the first asteroid to be discovered very early in the 19th century.

The white spots were actually suggested from the best Hubble space telescope pictures you could get that they were just areas that looked brighter than elsewhere. As the Dawn spacecraft approached, the most obvious one came into view.

In the middle of this crater that's tens of kilometres across, we have areas kilometres in size which are highly reflective. People were wondering what they were and people are still not sure. I went on the "Dawn" mission website just now, and there's a popular pole on the go, you can vote for what you think the white spots are.

10% of people think it's some sort of volcano - presumably an ice volcano - nobody thinks it's a hot lava volcano; 6% said they're geysers; 6% said they're made of rock of some kind; 28% said ice; 11% said salt and 39% said other, so I don't know what they were thinking.

Chris - But now we do have this week some new data, in the form of these two papers in Nature, which are using data and measurements made by the Dawn spacecraft. So this gives us a much clearer idea as to what these things are. So what are those papers saying?

David - Well we do have a better idea. One paper, which is based on data from the framing camera, they're showing that the central parts of the white spots, probably, are some kind of salt - a hydrated version of magnesium sulphate, and you can see a haze rising about the white spot...

Chris - So that suggest something coming off of the white spot which is scattering light around it?

David - Absolutely, something is coming off the surface and it seems to be water vapour, but sublimed off some ice, carrying dust particles with it. So the source of the water or the ice available to sublime when sunlight hits it is being replenished each day on Ceres because the available life sublimes when the sunshine hits, then it ceases to the sublime, the haze disappears, you don't see it at dusk. By the next dawn there's enough water ice arrived at the surface to sublime to produce a fresh haze, so there's some active internal transport going on and that's very exciting.

Chris - So is this water coming from inside somewhere then?

David - Yes, I think the water, which is feeding the haze, must be coming from inside Ceres.

Now there's no evidence, unlike many of the larger icy moons, that Ceres has an internal ocean of liquid water - that would be very surprising, we can't imagine a heat source to keep it warm enough for there to be liquid water. So it's just ice, not too far below freezing point, that's convecting and moving around maybe.

To be honest we're flummoxed, we don't really know, but the evidence is stacking up to suggest that the places on the surface where ice is being replenished and able to sublime a way to space, and you get left behind these hydrated salts.

Chris - And why is this important, or how does this remodel, or refashion or view and our understanding of the solar system? How everything we have and we see today got where it is now?

David - Well, to have so much water inside Ceres is a problem. Ceres orbits not too far beyond Mars, much closer than Jupiter, and it's this side of the snow line. Get to about Jupiter's distance from the Sun, it's cold enough for lots of ice to condense directly from the solar nebular when the solar system is forming.

Where Ceres is now, for most of the time at least, has been too warm for a lot of water ice to condense so it's possible Ceres form further out from the Sun and has migrated inward. And that probably brings us onto the second paper in the same issue of Nature which is providing us that Ceres is from even further away because it is suggesting that the surface contains what they are describing as ammoniated phyllosilicates - that means clay minerals with ammonia trapped within them.

But nitrogen or ammonia trapped inside Ceres is a very big problem if Ceres grew where we now see it, and the suggestion from this work is well maybe Ceres started off in the very outer solar system - Pluto or beyond - and somehow found itself way inwards. So it doesn't look like the archetypal biggest asteroid any more, it is a guest in the asteroid belt, and it's a guest that's the mystery we now need to try and solve.

21:21 - The antibiotic apocalypse

The antibiotic apocalypse

with Mark Holmes, University of Cambridge, and Nick Brown, Addenbrooke's Hospital

News broke recently of bacteria discovered in China that are now resistant to antibiotics used normally as a last resort, prompting fears we could be on the cusp of an age where bacterial infections are no longer curable. So are we all doomed, or is this scare-mongering? Georgia Mills puts the problem under the microscope for us...

Georgia - On the 11th December, 1945 a man named Alexander Fleming won a Nobel Prize for the world-changing discovery of antibiotic penicillin. Penicillin and drugs like it work by either killing bacteria or rendering them ineffective, and they’ve completely changed the face of modern medicine. Upon receiving his prize, Fleming gave a speech during which he mentioned the threat of antibiotic resistance. Fast-forward 70 years to the present day and headlines are cropping up everywhere about bacteria growing resistant to so-called "last resort" antibiotics. The words "post-antibiotic apocalypse" have even been used. So how worried should we be, and how did we get into this mess? I went to visit Dr Nick Brown, a consultant medical microbiologist at Addenbrooke’s hospital in Cambridge...

Nick - Resistance is a natural phenomenon and in many respect, I think, it can be inevitable that following exposure, bacteria will develop resistance. The bacteria mutate so that they are able to evade the action of the antibiotic. The key to the current problem, I think, is that whereas in the 1950s and1960s, whenever antibiotic resistance developed, we were able to replace an antibiotic with a new one. Now we are in a situation where there have been no truly new antibiotics in the last 20 years or so and, one of the big concerns that we have now, is the pace in which resistance appears to be proliferating is increasing.

Georgia - So why is the rate of resistance increasing? Well, we’re using antibiotics all the time in medicine. They’re used in hospitals for operations and are prescribed by doctors but, humans are not the number one user.

Mark - The vast majority of the antibiotics that are used are in this country and in Europe are used in the therapy of infectious disease in farmed animals.

Georgia - That’s Dr Mark Holmes from the Department of Veterinary Medicine at the University of Cambridge.

Mark - Well, the big problem is not that we use too much antibiotics on healthy animals but we probably have too much endemic disease in farm animals. You and I will favour cheaper meat and the farmers and the agriculturalist are very good at developing husbandry systems that produce cheap meat. The downside is that these animals are relatively stressed so they tend to have higher levels of endemic disease. There’s another issue and that is to keep the costs down, it’s not feasible to treat individual animals so, if you get a pen of animals and you get one or two that develop diarrhoea, then the antibiotics tend to be given to the whole pen rather than to the individual animal, and that is probably something that is less than ideal from the point of view of generating antimicrobial resistance.

Georgia - If we keep going at this current rate, what kind of world do we have in store for us? Nick…

Nick - As close as some parts of Southern Europe, there are infections in patients where there are no antibiotics left to treat infections and in those situations, obviously, the outcomes of severe infection are poor. Going forward some years, you would think that there’s a possibility that some infections that we now take for granted can be treated, might not be able to and that threatens the very nature of the way that we practice health care at the moment. For example, without antibiotics we wouldn’t be able to have a safe hip replacement; without antibiotics you couldn’t have cancer chemotherapy, you couldn’t have a kidney transplant so, antibiotics are absolutely vital to the way that we live at the moment and the way in which we expect our healthcare to be delivered.

Georgia - It’s quite scary stuff. So what do we do about it?

Nick - There are lots of things that being done about it. One is to try and protect the antibiotics that we do have left and that is trying to improve the way that we use antibiotics; don’t use antibiotics when they are not needed. Then the second broad area in which we can try and attack this issue is to consider how we can get new antibiotics into development and onto the market and, again, there are lots of initiatives to look at small drug discovery companies and, indeed, into the larger pharmaceutical companies to try and re-stimulate this market which is broken for many reasons, including for the fact that it’s not a financially viable market for those companies at the moment.

Georgia - If anyone is looking for new mould, I think I have some species as yet unknown to science in my fridge. But what about the current rates of use in agriculture? Dr Mark Homes…

Mark - The main issue here is our drive for cheap food and a free market economy. Farmers are under incredible pressure to produce foods at lower and lower costs, and you and I as consumers, through our purchasing power at supermarkets, are responsible. So it’s the system that’s at fault, not individual interest groups and most of the time we deal with this with legislation. So, in China and in North America, antibiotics are used for growth promotion, so healthy animals can be given antibiotics to make the sort of grow faster – something that goes back to producing cheap food. In Europe, we recognise that using antibiotics for growth promotion is not a good idea and we have legislation in place. That creates a level playing field, so we need strong regulation and strong leadership.

27:51 - The sorry state of our soils

The sorry state of our soils

with Professor John Quinton, University of Lancaster

We're dishing the dirt on one of the Earth's most precious, but declining  resources; it's not an animal or vegetable but a collection of minerals - more specifically, soil. 2015 was declared the year of soil by the UN, and this week they released a much-anticipated report on the state of the world's soils. Unfortunately the results aren't good. John Quinton is a soil scientist from Lancaster University and he joined Kat Arney to fill her in on what the report said...

resources; it's not an animal or vegetable but a collection of minerals - more specifically, soil. 2015 was declared the year of soil by the UN, and this week they released a much-anticipated report on the state of the world's soils. Unfortunately the results aren't good. John Quinton is a soil scientist from Lancaster University and he joined Kat Arney to fill her in on what the report said...

John - The highlight from the report was that we really need to stop degrading our soils. The report suggests that we're losing around a football pitch's worth of soil every five seconds, which is quite mind blowing really. We also need to stop the decline in soil carbon, so soils hold onto about a third our carbon and we're losing that back up into the atmosphere. We also need to rebalance the amount of nutrients in our soil, so some soils in some parts of the world have far too many nutrients and in other parts of the world they just don't have enough. And then the final point that they make is just that some of the data that we have on our soils around the world is just really, really old and we need to update it.

Kat - And in terms of what we do know, given that the data is kind of old, what do we know about the kind of degradation that's facing our soils?

John - The kind of data that we have would suggest that around about a third of the world's soils are degrading, and the biggest threat to them is soil erosion. So that's either by wind erosion where we've got dry soils, often in arid areas, which are just getting blown away, and then the other form is through water erosion. So this again is when surfaces are exposed to the elements, and we get a heavy rainstorm, and it's actually washing the soil off hill slopes and down into the rivers and then perhaps out into lakes or even into the ocean. So those are the two ones we're worried about in agriculture but we're also concerned about the area of soil which is being paved over. More and more of us are living in cities and as we move into the cities, we cover the soil in concrete. In Europe, an area round about the size of Cardiff is paved over every year, so that's another threat to the functioning of our soil.

Kat - So can we lay the blame really at the expansion of the population and the expansion of agriculture. Are these the main drivers of the problem?

John - I think we are clearing a lot of land to produce food. We're going to have what, around 9 to 10 billion people living on this planet by 2050 and they're going to need feeding and that's going to mean that we're going to need land to grow crops in them, so that's really going to be one of the big pressures and when you convert forest or grassland to agriculture, you degrade the soil.

Kat - And that, I guess, is the problem is what is the risks of losing so much soil like this? Why should we care? I mean it's just dirt, isn't it?

John - Just dirt. Gosh, heathen. It's the brown gold beneath your feet. The living skin of the earth. Scientists that around about 10% yield reduction by 2050 due to erosion, so that's equivalent to losing a 150 million hectares, is no longer going to be productive, so it's serious stuff.

Kat - But is just food that's at risk here?

John - So the other big concerns would be around carbon. Soils store round about a third of the world's terrestrial carbon, so more than all the forests and all the atmospheric carbon combined so, if you lose the soil, you lose that store. The other thing that soils do for us is to keep us supplied with clean water. Most of the water that falls on the terrestrial surface is going to hit the soil before it ends up in rivers and lakes and so soils play a really important role in both buffering and attenuating the flow of water, but also of cleaning it up. It's also packed with organic matter and soil micro-organisms and those things are actually, you know, pulling out all those nasty chemicals that we don't want to get into our water supply, and helping to produce clean water for people. So that's another threat we need to be concerned about.

32:33 - Getting to the root of the issue

Getting to the root of the issue

with Professor Chris Collins & Dr John Hammond, University of Reading

One of the biggest reasons we're in this sorry state is because of population  growth and the resulting intensification of agriculture. But is the poor quality of soil subsequently impacting our food and ultimately therefore, our health? Graihagh Jackson went digging in the dirt with Reading University's John Hammond...

growth and the resulting intensification of agriculture. But is the poor quality of soil subsequently impacting our food and ultimately therefore, our health? Graihagh Jackson went digging in the dirt with Reading University's John Hammond...

John - So we've just dug up some soil here and you can see straight away there's a huge diversity of ingredients in the soil. The soil provides a number of things, water, but also some mineral elements; nitrogen, phosphorous, potassium, calcium, magnesium, and sulphur are the six main ones, and then there's some micro-nutrients that are in there like iron, and copper, and zinc which go into really important functions in the plant

Graihagh - Like what, because I think I need calcium to make my bones stronger, so does the plant need say, phosphorous or nitrogen for?

John - Nitrogen's the biggest one. The plant needs that in the greatest quantity and that goes into making things like proteins so, if we don't get enough nitrogen in the plant, then the plant can't make chlorophyll and so the plant starts to look yellow.

Graihagh - How does it get from the soil then, into the plant to make the chlorophyll, and make the plant grow ultimately?

John - The plants take up those nutrients from the soil solution, so it's moving water through the soil, up into its roots and out through its leaves, and with that flow of water it can bring with it some of those nutrients. In particular, nitrogen and sulphur come through that pathway. Some of the nutrients like phosphorous and potassium, they are harder to move through the water, so they have to move through a diffusion process. So they move from a high concentration in the soil to a low concentration so that when the nutrients get to the root surface, there's a number of proteins in the root cell that then transport those nutrients.

Graihagh - And this ultimately enables the plant to grow from a seedling all the way up into an adult crop?

John - That's right.

Graihagh - If there are any toxins in the soil, would they be also taken up just like the nitrogen and the phosphorous you were talking about?

John - Yes. So some heavy metals that we sometimes find in the soils can be taken up through the same process into the plant and, ultimately, into what we would eat.

Graihagh - That's not the only way you could ingest heavy metals though. You could eat the soil itself. I know what you're thinking, I don't eat hunks of soil for dinner but, it's actually a lot more common than you think.

Chris - Usually they say about 1% of the weight of a vegetable is the soil attached to it.

Graihagh - I know, I was quite surprised too - 1%. That's a colleague of John's at Reading, Chris Collins. And think about it, how well do you really wash your veggies? I'm definitely guilty of not scrubbing as well as I should, so there's probably much more than 1% of my vegetable that's actually soil...

Chris - Carrots, because there in such intimate contact with the soil are often more contaminated than other crops where the edible portion is above, say for example, a tomato would be much less likely to be contaminated than a carrot.

Graihagh - Although that's a little hard to stomach, I can't help but think, how bad can it be? Surely our soils, and certainly the soils that are used to grow food can't be all that polluted - right?

Chris - They're very common. In any urban area you will find detectable levels of lead, from old lead piping, lead in petrol and you will also find elevated levels of the organic pollutants mainly associated with transport but also, for example, a lot of people used to put the ash from their fires into their gardens because they thought it had a nutrient value. What they didn't realise, is there are some of these organic pollutants associated with those ashes.

Graihagh - What Chris researches is what happens when we eat this polluted soil. He took me to a lab where they're simulating the gut tract from your mouth to your anus.

At one end the polluted soil goes in and is mixed with an acidic solution to recreate the conditions in the stomach. Next is the small intestines where it's a little bit more alkaline, so the solution in the stomach jar is moved into the intestine jar where something is added to bring that pH up to a more neutral level. The next bit is the colon and it's where things took a turn for the worse.

Chris - You can get it now.

Graihagh - Oh yes. I mean it's not great. It's getting gradually worse, isn't it?

What could be so bad? Well, this is where Chris takes his intestinal samples and mixes them with real human poo. Yes, you did hear me right. Hominid excrement - and it stinks.

Chris - It's like being on a farm isn't it?

Graihagh - Yes, but the worst thing is, is I know this is human. Whereas cows, it's slightly more acceptable

Chris - It's slightly sweeter, isn't it?

Graihagh - Why put yourself through hours of lab time surrounded by the sweet scent of excrement I hear you ask. Well, these pollutants are syphoned off the soil, left to float around in the gut solution and absorbed into your body. What's known as bio-accessible.

Chris - What we're looking for is the bio-accessible fraction so, that is the amount of pollutant that is desorbed from the soil into the gut solution.

Graihagh - And how much is bio-accessible from your experiment here?

Chris - 10 to 30% goes into the colon solution.

Graihagh - How much of an affect does your microbiome have on how much of these pollutants you absorb.

Chris - We really don't know because this hasn't been tested. One thing we did test is whether using a polluted soil changed the population composition of the microflora, and actually in the soils we used we didnt find a significant difference between the polluted soils and non polluted soil.

Graihagh - Does it make a difference to how accesible those pollutants are?

Chris - That might make a superficial difference. They might break them down and turn them into more benign compounds, so they might hydoxilate them for example, which makes them more water soluble and then more likely to be passed out.

Graihagh - Is there any evidence to suggest that that whole 10 or 30% is then absorbed into the blood?

Chris - Truth is we really don't know. There's been tests in pigs, but there's a lot of metabolism of organic compounds when they're in the body, so it's really difficult to test it.

Graihagh - But I suppose the danger of it being in the bloodstream is that blood goes everywhere. So equally, if it's not metabolised elsewhere in your liver and excreted through your urine, it could end up in your brain or whatever?

Chris - There is some sort of secondary activity on that, so it's unlikely that the whole amount would be exposed to one particular target organ, if you like, but there is the potential.

Graihagh - I'm not sure how much more of it I can stomach in here. I can feel myself holding my breath slightly.

Chris - It's not the most pleasant place to work - but good science.

40:02 - Stopping erosion in its tracks

Stopping erosion in its tracks

with Richard Bardgett, University of Manchester

The plea to take our soil health seriously is a strong one - our food, our safety and our climate depend on it - but how do we go about taking better care of our soils? Is it possible to rejuvenate our soils and if so how? Soil ecologist Richard Bardgett from Manchester University took Kat Arney through the options...

Richard - It certainly is possible to rejuvenate soils and it’s quite remarkable, when you look around the world at soils that have been affected in the past, how resilient the really are. I mean, you can find soils that were completely obliterated during the First World War that are now showing signs of soil health and restoration; so it really depends on the extent to which they’ve been degraded. But I think one key thing about restoration of soils is that the rate of soil formation is extremely slow. I mean, where I live around here, most of our soils are around 10,000 years old and they will have formed about 1 metre of soil. So it takes, on average - I mean it varies, obviously, from place to place - but about 1.1mm of soil is formed per year on average; so it’s a very slow process. But, having said that, there are things you can do and John’s mentioned a few. I mean the first is stopping the forces that cause soil degradation like continuous cultivation, etc., and really key to it is restoring the organic matter and recycling of nutrients within the soil system.

Kat - So my mum is a keen gardener and, you know, I always think if you want to improve your soil you just chuck a bag of manure on it. Is that the main solution or are there other ways of preserving soil and making it better?

Richard - Well that might be a good solution in a garden but I don’t thinks it’s going to be a solution to restoring soils around the world. I think key to restoring them is getting organic matter back in them and restoring the soil community – the food web or the living soil – all the different types of organisms within there and that, to me, is really crucial to restoring soil functions within degraded landscapes.

Kat - So does this mean changing the way we use soil? Changing the way that we farm basically?

Richard - Absolutely, and there are certain things that you can do relatively easy in some parts of the world. I mean there’s different cropping practice like crop rotations, no till agriculture which is a form of agriculture where the ground isn’t ploughed, but the other thing you can do is by selecting different types of crops that can actually promote beneficial organism in the soil.

Kat - Given that it does seem to be the way that we’re farming that’s leading to quite a lot of the degradation in our soils, the loss of our soils, and changing to more sustainable farming methods that are kinder to our soils. Are we still going to be able to feed a growing population?

Richard - I think a lot of the management options potentially have a trade off in terms of short term yield reductions but I think there is a possibility, through things like crop breeding and engineering of the (03.03), for example. We are beginning to learn that roots exude different kinds of chemicals through them which act as signals to warn crops of oncoming pests, for example and, also, we’re beginning to learn that different root characteristics, or combinations of root characteristics, can promote the growth of certain bugs in the soil which improve nutrient acquisition, etc. So I think it’s certainly something we can’t ignore for the reasons that we’ve talked about.

43:43 - Growing Truffles in Australia

Growing Truffles in Australia

with Al Blakers, Manjimup Truffles

Studying the relationships between plants and the soil has reaped some benefits in the commercial world. And one winner is Al Blakers - Australia's first truffle farmer. Truffles are a highly prized food delicacy, but they're very hard to farm: sapling trees need to be inoculated with the fungus when they're young. This sets up what's known as a mycorrhizal relationship between the two. The fungus brings nutrients to the tree, and the tree roots feed the fungus sugars in return. The fungus fruits by producing buried, golf-ball sized structures full of spores, otherwise known as truffles. Chris Smith went along to see how Al does it at Manjimup Truffles in the southwest corner of Western Australia...

Al - They’re the fruiting body of the mycorhizzal fungus. Now, every plant in the world's objective is to reproduce – this is what that’s about. We’ve just learned to manage it and grow it in a fashion where it’s a viable industry.

Chris - Those would sit just below the surface of the soil then? What, attached to the root of the plant that had grown them?

Al - Every truffle is attached to the plant. Usually you’ll find a fine root; sometimes they have totally grown around the root - you actually harvest them and they’ve got a root sticking out each side!

Chris - Can we try a bit?

Al - Yes.

Chris - They’re about the size of a walnut – give or take aren’t they? How much do you think that weighs?

Al - These are small ones. That one there’s probably 8 to 10 grams.

Chris - How would you describe that flavour? It’s a sort of; it’s a subtle flavour. It’s nutty; its nice.

Al - Oh yes. It’s a brilliant flavour; everybody’s got their own comment. A lot of them say "seafoody". I say "earthy, nutty" you know, but everybody’s got a different take on it.

Chris - And these are truffles from Europe? They’re a strain from Europe that you have established here in Southwestern Australia?

Al - Yep. There the Perigord truffle. They're the one from the Perigord region in Europe. We’ve had DNA done and we’ve actually got a nice mix of truffle here, actually of quite a few different strains. We thought we had one pure strain but it turns out we don’t.

Chris - How did you get them here?

Al - Ah yes. Well. We don’t talk about that...

Chris - Suffices to say then, you got the truffles here in the first place! And what about the trees you’re growing them on?

Al - Ah well, we collected seed of every known hazelnut and oak tree we knew in the state. That’s where we started from. We had a lot of heartache here in the first few years, learning how to germinate the hazelnut tree. It’s a little bit tricky to grow that is on a tree and we got that figured, and the Oak trees, well, we weren’t sure what Oaks to use so we used every one we could find. As it turns out there are only three or four oaks that are suitable and that’s what we use now. We’ve learnt a lot in twenty years.

Chris - Why did you need to grow them from seed?

Al - You can inoculate and get the fungi onto it when it’s a very small plant. The bigger the plant the more it’s costing.

Chris - Right. So you had to start with a seedling and you establish the relationship with the truffle-producing fungus as a seedling in your nursery? Is that what you’re saying?

Al - Yes.

Chris - You plant those trees out onto the land here. How long between the sapling going in the ground and then you beginning to get truffles off its roots?

Al - Well, we have seen it in 5 years, but about year 7 or 8 you start to get some decent production. Once it kicks off it usually quadruples each year. So if you get 400 grams, you’ll get 1.6 kilos and you know it goes, and goes, and goes into about year 12/13 and then it sort of starts to steady. We are getting into a stage now where we’re trying different techniques to keep the trees highly productive – that’s the next big challenge.

Chris - How do you get the truffles out of the ground? How do you find them?

Al - I just use the dog there.

Chris - Not pigs? Because in Europe they us pigs don’t they?

Al - Yes, but I like my fingers!

Chris - What do you mean?

Al - Pigs want to eat the truffle. The dog hasn’t got the slightest interest in eating the truffle, he just wants a treat off you. That’s why my dogs are fat!

Chris - I did see some rather large labs… they look like Labradors. Are they Labradors?

Al - Yes, they’re labs.

Chris - You train them to go and sniff out the truffles?

Al - Yes, that’s their job. Twice a day they go out and sniff around and then they get nine months off.

Chris - And then you reward them every time they find one, which would explain why they are quite rotund. That one we saw earlier was quite big.

Al - Ah, he’s just a big boy – a bit like the owner!

Chris - Do you weigh the dog at the end of the season to tell how many truffles you’ve found because, presumably, the scale of the size of the dog is proportional to how many treats he’s had?

Al - I just check the book!

Chris - We’ve just sat here and cut some slices off and eaten then though. Does it not feel to you a bit like you’re sort of eating 20 dollar notes, because they’re quite expensive aren’t they?

Al - Ah, they’re only 5 dollar notes, but yes you get over it – eventually.

Chris - Do you end up… because you’ve got a huge basket of the here? Do you end up having a truffle for tea or are you sick of them now? Do you eat them?

Al - Occasionally.

Chris - When should you put truffle in with your recipes?

Al - You never cook truffle; you add truffle after the cooking’s done.

Chris - Because we’ve been eating these raw. Is that the best way in your view?

Al - The best way to eat it is to make a truffle butter. Chop it up in little pieces, nearly melt down some unsalted butter and put the truffle through it and let it set and just drop it on top of the steak. I reckon that’s the best way in the world to eat it.

Kat - Oh God, that sound absolutely amazing. That’s truffle farmer, Al Blakers. So Chris, did you bring back any truffles?

Chris - A bit of a confession, Kat. It’s actually quite tricky to move these things internationally you see so, as Al gave me all the truffles we dug up that morning, I had this bag full of them; and there was about £300 worth of truffles in this bag. I was driving back from Manjimup towards Perth and I went past this extremely nice looking winery called St. Aidans, in the Ferguson Valley. It’s run by a guy who’s an anaesthetist called Phil Smith, and he makes exceedingly nice wine, and I just found myself accidently trading him my bag of truffles for lunch in his winery at St. Aidans and some rather nice wine. So "no" is the answer!

49:48 - Save our soils: Why we need to act now

Save our soils: Why we need to act now

with Professor Richard Bardgett, University of Manchester & Professor John Quinton, University of Lancaster

If no action is taken, we'll lose 1.5 million square kilometres of land from crop production by 2050 - that's equivilant to all the arable land in India. But it's not just down to policy-makers; there are things we can all do as individuals to help save our soils, as John Quinton and Richard Bargett explained to Kat Arney...

Kat - Richard, why has no focus been paid to our soils until now? Why is now the time when we really need to pay attention to them?

Richard - Well, I think more people live in cities so they are more distant from contact with the soil because, in the past, on a daily basis, people would come into contact with soil and actually rely on it more.

Kat - John, what happens if we don’t do anything?

John - We don’t eat. That’s the biggest problem. If there’s not soil, we can’t grow any food and we will all die. We would have extensive, barren, rock with little biological activity so all the plants and animals that we see on the Earth’s surface at the moment just wouldn’t be there. You know, if I take you back what around about 4 billion years after the Earth was formed, it was really the formation of soils at that point, with the evolution of biological life on the planet, that brought the atmospheric CO2 concentration down and enabled things to grow and live on the planet. So I guess, if we remove the soil at this point, that’s where we’re going back to, a very different world to the one that we all live in at the moment.

Kat - The kinds of things we’ve talked about, so far, involved things like farming systems, policy, agriculture, global change that we need to bring about but, are there any things we can do on an individual level you know, are there any things we can do in our local environment? Richard, what do you think?

Richard - Well, I think there’s an enormous number of things that people can do. I mean you only have to look back to the Second World War, for example, in the Dig for Victory campaign. Cities, or people in cities, produced enormous amounts of food which helped to sustain the population at that war time, and I think now, there are many opportunities for people to grow their own food; community gardens are booming for example, allotments etc. So this is another way of people getting more contact with the soil an actually building the fertility of soils for a growing world population.

Kat - So John - what do you think we can do save our soils on a local level?

John - At a personal level, recycling your organic material that you’re consuming which originally came from the soil, and getting that back to soil so, having a compost bin can only be good because you’re helping to kind of close that cycle a little bit. So, I’d encourage everybody to get into recycling and try and restore their own soils in their back yard, or their allotment, or in other places in their local environment.

52:27 - Why do I sleepwalk?

Why do I sleepwalk?

Felicity Bedford has trying to find out the answer to this one with Dr Ian Smith from the sleep clinic at Papworth Hospital...

Felicity - I don't think I ever sleepwalk but I wonder how many people don't know that they have strange nocturnal behavior. I spoke to Dr. Ian Smith from Papworth hospital's sleep clinic who explained how a snooze can lead to a late night stroll.

Ian - Sleepwalking is almost normal in children; up to a fifth of children will do it at some stage, usually with no important consequences. Sleepwalking starts in deep sleep, and this is deeper in children than in adults. This deep sleep stage is the most refreshing and seems to be important to brain repair and memory sorting, but memory itself is switched off during deep sleep. And so one feature of sleepwalking is that the walker usually has no recollection of what's happened. Some stimulus - a noise, being jogged, an irregular patch of breathing - jolts the sleeper out of deep sleep into a mixed wake-sleep state. Most people would just fall back to sleep, but those prone to sleepwalking will get up and start roaming without waking completely. Typically, the walker will have their eyes open but will not fully interact with other people. They'll often navigate obstacles skillfully but may not recognise dangers: they might for example try to climb out of a window; usually an episode lasts just a few minutes and then the walker returns to bed.

Felicity - Is there any particular reason you might be prone to wandering around the house like a zombie in the dead of night?

Ian - Sleepwalking runs in families, and in some people a marker has been found in the genetic code which is strongly associated with the condition. It is not advisable to try and wake a sleep walker as they may be confused and aggressive.

Felicity - That's good to know, but if sleepwalking is in your genes, is there anything you can do to prevent it?

Ian - In managing a sleep walker, we would look to reduce triggers which include irregular sleep habits, stress, alcohol, some antidepressants, and sleep apnoea - that's interrupted breathing during sleep. Occasionally, people put themselves and others at risk during sleep walking and medication can reduce the frequency of episodes. Simple precautions for safety include locking upstairs windows, removing sharp and fragile objects from the bedroom. In people with disruptive sleep walking we would recommend referral to a specialist sleep clinic.

Felicity - Thanks Ian. I hope that helps Sterling, and that answer means you can sleep easy now. Our next question is from James...

James - So what are the bags you get under your eyes when you're tired? One thought: they're facial markings that have evolved to warn people away from crabby, bad sleepers!

Comments

Add a comment