Half of all children with a genetic tendency to an anxious temperament go on to develop severe anxiety or depressive problems later in life, new research has shown.

Anxiety and depression are becoming increasingly common, particularly in young people, with more than a quarter of individuals affected at some point each year.

The environment in which we develop and grow up has the potential to affect significantly our disposition to be anxious. This ranges from events during pregnancy to nurture, diet, nutrition, and experiences later in life.

It is also known that you are more likely to suffer from anxiety or depression if your parents do too. According to published statistics, more than a third of the variation in anxiety-like tendencies is explained by family history.

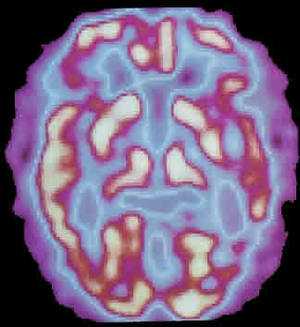

However, the parts of the brain responsible for causing this genetic tendency aren't well defined. Now a new study has found that, although brain volume is significantly affected by genetics, it is brain metabolism that forms the vital link between genes and the risk of developing severe anxiety or depressive disorders.

Dr Ned Kalin and chis olleagues at the University of Wisconsin in Madison carried out a systematic study involving 592 young rhesus monkeys which were part of an extended family tree.

By studying the animals' behaviours, they were able to observe a tendency towards anxiety being passed down through the generations.

In the study, putting the monkeys in a stressful situation, where a person stood still and avoided eye contact with the monkey, led to the more anxious individuals freezing in one position and stopping all vocalisations. Less anxious monkeys, on the other hand, turned a blind eye to the human cold-shoulder and continued their normal behaviour.

Using high-resolution functional and structural imaging to study what was happening in the monkeys' brains, the researchers found that the anxious behaviour was associated with higher activity in certain brain regions. And this tendency towards an elevated metabolic rate in these areas appeared to be an inherited trait.

Critically, this pattern of behaviour, dubbed an "anxious temperament" by the team, mimics closely reponses seen in human children too.

"You'll be more vulnerable to develop more severe problems if you have this genetic tendency, which is associated with increased activity of those brain regions," says Kalin.

Moreover, 50% of children with anxious temperament go on to develop some form of psychiatric disorder as they grow up.

This study provides us with the option of producing more targeted treatments for anxiety and depressive disorders.

But these "don't have to be medication treatments," Kalin says. The research will enable the development of behavioural treatments for those children that are most at risk.

In particular, Kalin stresses its importance in "directing treatments at parent-child interactions in ways that can promote not only changes in behaviour, but changes in the brain systems that we know are overactive..."

References

- Previous Cause of brain ageing discovered

- Next How old are you really?

Comments

Add a comment