Should we always trust a study with an easy solution? Scientists have found that it never hurts to check, as Kat Arney explains to Chris Smith...

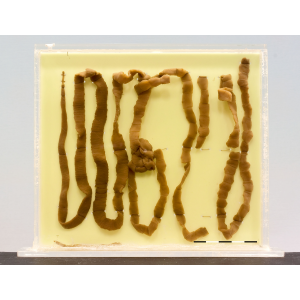

Kat - What I've noticed this week has been a really, really fascinating study.  It hasn't actually been picked up that much but it's from researchers at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. What they've done is reanalysed data from a study that was published over 10 years ago. Now, the study that was published 10 years ago, it was done in schools in Kenya which looked at the effects of giving deworming tablets to children and as well as the obvious health benefits you might expect - i.e. the children didn't have so many worms - they found in this original study that more and more of the kids went to school and that's presumably a good thing. Lots of development agencies saw this study and were like, "Yeah, this is brilliant! Deworming tablets, really cheap, give them out to kids, and they will go to school more." Everyone accepted that this was a brilliant idea. Now, the researchers from LSHTM, the researchers that have done this reanalysis, they looked at the data from that original study and they analysed it in exactly the same way as the original researchers had done, and they came up with different answers which is a bit dubious in the world of science when you take the same data and you crunch it in the same way.

It hasn't actually been picked up that much but it's from researchers at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. What they've done is reanalysed data from a study that was published over 10 years ago. Now, the study that was published 10 years ago, it was done in schools in Kenya which looked at the effects of giving deworming tablets to children and as well as the obvious health benefits you might expect - i.e. the children didn't have so many worms - they found in this original study that more and more of the kids went to school and that's presumably a good thing. Lots of development agencies saw this study and were like, "Yeah, this is brilliant! Deworming tablets, really cheap, give them out to kids, and they will go to school more." Everyone accepted that this was a brilliant idea. Now, the researchers from LSHTM, the researchers that have done this reanalysis, they looked at the data from that original study and they analysed it in exactly the same way as the original researchers had done, and they came up with different answers which is a bit dubious in the world of science when you take the same data and you crunch it in the same way.

Chris - So, how did that happen then?

Kat - Well, they think that there may have been some errors in the original analysis, and then when they reanalysed it in a different way, then they found even more differences in the data. So, it looks like although deworming kids is clearly a good thing for children's health, it doesn't actually make them go to school more.

Chris - Because obviously, this is really important because if you are trying to persuade people what to invest their money in from a sort of funding and an overseas development point of view and you say, "Right. Look, the linchpin is education and we want as many people going to school as possible. You should spend your money on worm pills." Actually, that may be spending your money on the wrong thing to get the outcome you want.

Kat - Exactly. It's this wonderful idea that you can almost pop a pill for anything. "Give these kids pills and they'll go to school." In fact, I think it's probably shown that you need more complex interventions. Although it's interesting, the researchers I was talking to about this and they said it may just be that because there were researchers in the schools, you know, a person with a clipboard turns up, you're going to go to school because otherwise, you're worried that you might look bad if you don't. So, it's nothing to do with the worming. But it's certainly very interesting and it highlights that there's a lot of data produced in a lot of studies and many people accept the conclusions and don't necessarily go back and go, "Is this really telling us what we think it's telling us? Who's checking these studies? Who's reanalysing these studies?" there's actually more of a movement towards doing this. There's a lot of research done by thousands and thousands of scientists around the world. Some of it is good, some of it is not so good, some of it, maybe needs reproducing, some of it is pretty robust. I think this is how science works. It's not necessarily a flora of science that some things are found to not stand up. But I think that there should be more acceptance that people can try and reproduce studies, make sure that findings are reproducible. The trouble is that, in a world of science, we love novelty, we love the new stuff, the exciting stuff. Not necessarily someone going, "Yeah, I did those experiments again and I got the same answer."

Comments

Add a comment