The key to evolutionary success lies in the nose, new research suggests.

Ancient predecessors of modern mammals possessed a highly developed sense of smell, which may be responsible for launching mammals into their present-day global dominance.

Mammals are a hugely successful group of warm-blooded animals with fur, or in the case of humans, hair. One of their defining characteristics is the size of their brains:

"Compared to all other organisms, mammals have the biggest brains that have ever evolved. And this seems to be one of the secrets behind their evolutionary success," said Professor Tim Rowe, lead author of the study.

To understand how the mammalian brain evolved, the researchers studied two tiny fossilised species thought to be ancestral to modern mammals, called Morganucodon oehleri and Hadrocodium wui, both only a few centimeters long.

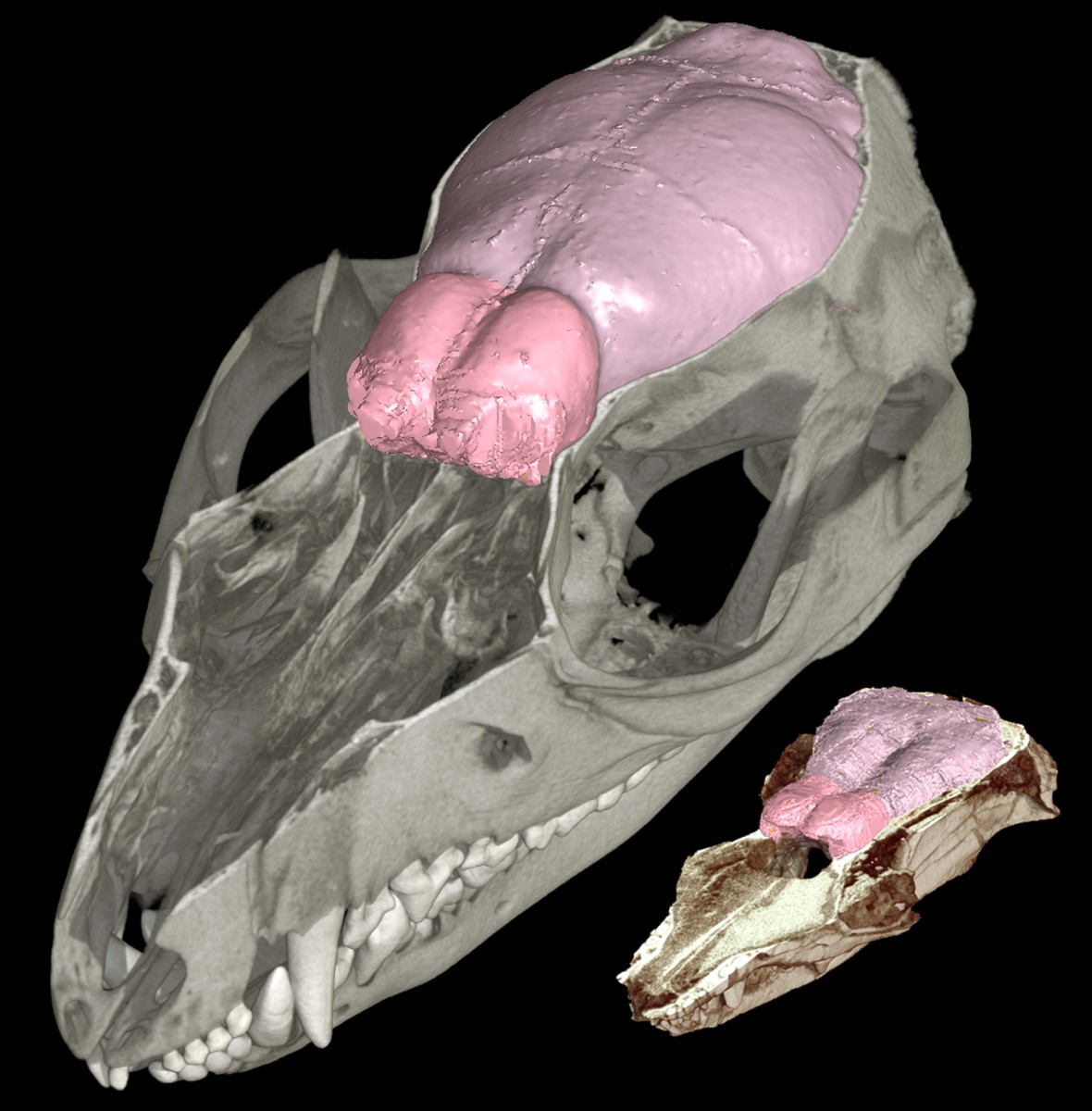

Because soft tissues do not fossilise they could not view the creature's brains directly. Instead, they scanned the fossilised skulls using 'Computer Tomography', or CT, whereby a computer generates three-dimensional images of an object using X-rays. This is the same technique used by doctors to visualise the inside of a patient's body.

"As the brain inflates and grows, it grows very rapidly, and it impresses its outer surfaces against the inner walls of the brain case [skull] that surround it," explained Rowe. "From an empty scull, by scanning it, we can digitally fill and extract that space."

Using this technique, the team generated 'endocasts', reconstructions of what the outer surfaces of the brain would have looked like in life.

They found that parts of the brain dedicated to 'olfaction', the sense of smell, were greatly enlarged in Morganucodon and Hadrocodium compared with non-mammalian relatives.

"Most of the increase that we've seen in the size of the brain in these two fossils is tied very directly to their sense of smell," said Rowe.

The authors suggest that mammal brains evolved in successive waves, or pulses, driven primarily by the need for greater processing of olfactory, or odour-based, information.

"Smell is complicated, the olfactory code is a very complicated code, and it requires a big computer, if you would - a big brain - to process all this," said Rowe.

The scans also showed another mammalian brain region, called the neocortex, was present in both Morganucodon and Hadrocodium. The neocortex is dedicated to receiving and integrating sensory inputs and directing fine motor outputs. Its presence indicates that ancestral mammals possessed an advanced sense of touch, possibly because of the hair covering their bodies, and also had sophisticated muscular coordination.

The research paints a picture of mammal brain evolution, driven by ever-improving sensory information processing, particularly the sense of smell. One pulse of brain enlargement is represented by Morganucodon, which evolved first, with a second increase in brain size documented by Hadrocodium, which appeared later in evolutionary time.

Humans, a much more recently evolved species, have sacrificed a lot of our inherited sense of smell in place of an incredibly sophisticated colour vision system. But these fossil skulls show that it's actually the nose that held the key to mammalian evolutionary success for most of the last 200 million years.

Comments

Add a comment