A woman in science: Indira Raman

Interview with

Now in each episode, alongside the research, we also try to delve in other aspects of practising science; previously we've looked at funding, or rather the lack of it, and we've also recently explored public engagement and developing the problem solving skills of undergraduates.

engagement and developing the problem solving skills of undergraduates.

This month, Chris Smith hears a personal insight into a perennial problem...

Indira - My name is Indira Raman. I'm in the department of neurobiology at Northwestern University.

Chris - What really struck me about your perspective in eLife this month Indira, is that you opened by saying, "In my 18 years as a professor of neurobiology, I've been asked to speak as scientist because I'm a woman. But this is the first time I've been asked to speak as a woman because I'm a scientist." Elaborate.

Indira - Well, as one knows, very often in many scientific venues, there's a growing interest in ensuring that a group of people that is speaking represents a diverse cross-section of the scientific population. And so, I've been asked to speak as a scientist because of my science but very often, I'm also aware that the organisers are interested in having a representation of women and I am a woman. But in this case, the focus was different and I was asked to speak about my experiences as a scientist because of being female. I chose to do it in a way that seemed to be compatible to me with my experience of talking about science.

Chris - How does this whole kind of, "I get asked to talk about science because I'm a woman" - how does that go down with you? It's good to be gender neutral but what I think would really upset someone is if they heard that and then thought they had been elected to appear on a programme because of their sex, not because they're good at science.

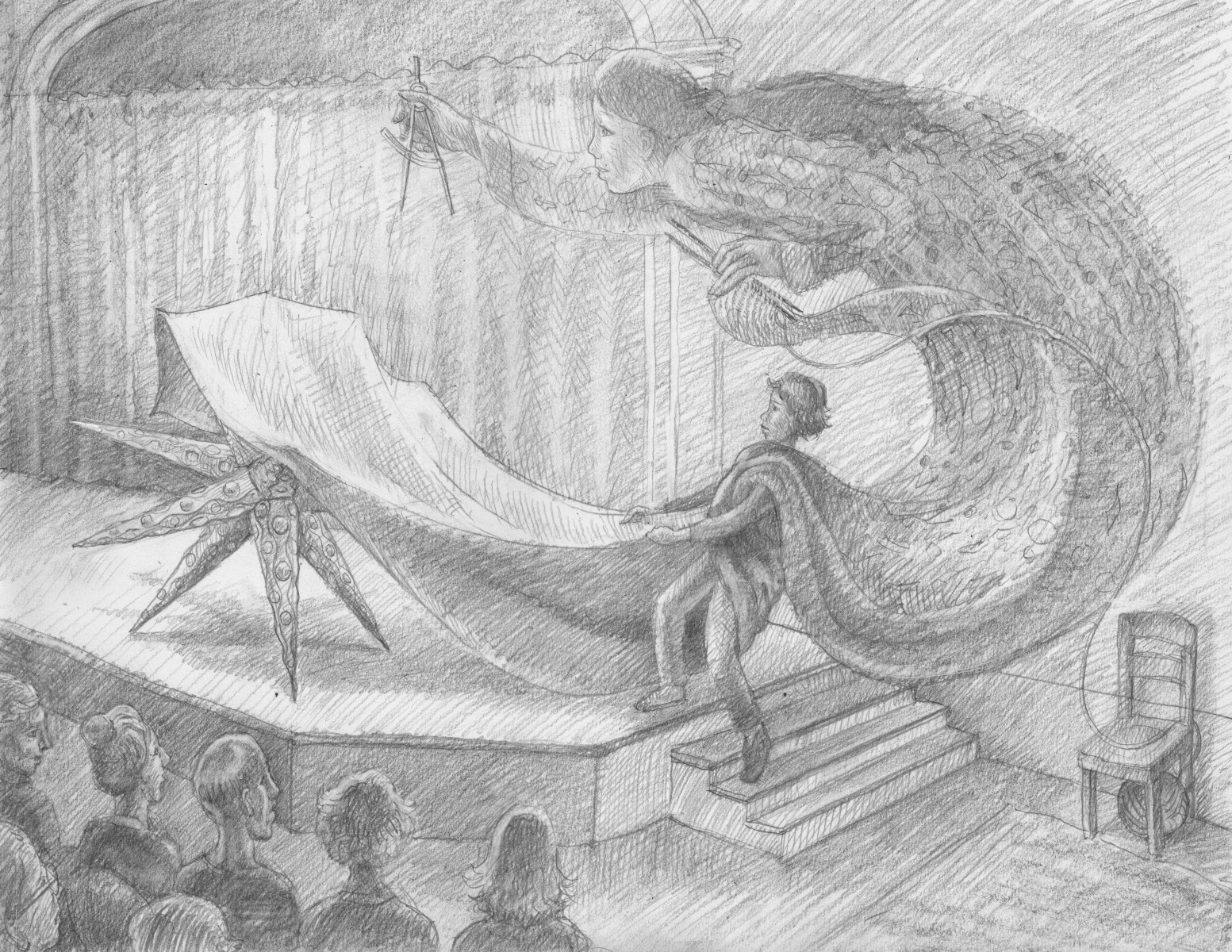

Indira - Right. I think that this is a central question of our time because on the one hand, we want to encourage diversity and I think that that's a laudable goal that I support. But we also want to maintain, as you're saying, the highest calibre of participants. I think those things sometimes work together and sometimes and sometimes move into conflict, and that's why I called it out at the beginning. That's why I mentioned in the piece, the way that I deal with that is internal with this idea that I walk on stage as a woman and walk off stage as a scientist.

Chris - In your view, why are we in the position we're in where we actually see that the bottom end of the scientific tree coming in, the input pipe if you like, has a very healthy proportion of women? But when you look at what comes out at the other end and turns into people of your sort of calibre, they've all vanished. You're a very rare species, why?

Indira - I don't think there's a simple answer to that question. There are many reasons why people stay in science. There are many reasons why people may leave it. There's one very straightforward element of being female that can be complicated to tie in with a scientific career and that's childbearing. There's a tremendous element of uncertainty and a lack of security through ones 20s and often ones 30s. Some people respond to what they see as a social dynamic within science. It can be very competitive. There is the intensity of the work where one really almost never goes home and leaves it completely behind them. As it turns out, there are proportionately more women who decide, "This career is not for me"

Chris - But the majority of the reasons you have highlighted apply to men too. But they don't leave in the same proportions or on mass the same way the women do, do they?

Indira - Correct. So for whatever set of reasons, there are more women who decide that those attributes of the field are elements that they don't really want to maintain in their daily lives.

Chris - People often talk about their being role models and the way to solve a lot of this is to have good role models. This will attract more people of a particular persuasion, gender background, whatever into a particular area. Do you go along with that or do you think actually that you can have as many role models as you like if the system is broken, as soon as you take the pressure off, it will just relapse back to the broken type it was to start with.

Indira - I think that it's important to think about role models in a broad sense and think what is it actually that you are wanting to model yourself after. My own experience was that I worked for 4 men as I was being trained. They were all white American men and they were tremendous role models for me because what they modelled for me was a way to do science, a way to be just in one's thinking and careful in one's thinking, and humane in one's behaviour. And those were the things that I wanted to have modelled. I should say that I am half Indian from India and half Caribbean. There was nobody like me. It was very unlikely I was going to find a half Caribbean, half Indian female role model who was doing electrophysiology for me to model myself after. And so, I found other ways of recognising pieces of myself in people who didn't happen to share many of my attributes. I have found it possible to be a role model for students from all over the world - male and female. A big discovery for me when I was an undergraduate was finding out that there were other people at my college from many different countries who actually shared many of the experiences that I had. And so, I think that as we learn to expand our notion of role models, we will be able to reach across the divides because otherwise, we'll never change the proportions of people in science because we'll be operating on the assumption that one can only train someone who is like you.

Comments

Add a comment