If you're reading this, you have almost certainly experienced pain. Whether it's the sting of a paper cut or the agony of a shattered bone; pain shapes much of our lives, and can sometimes even ruin them. So what is the point, evolutionarily speaking, of pain? Wouldn't we be better off without it?

|

|---|

What exactly is pain?

In order to understand why pain exists, we must first understand what it is and how it works. There are two types of pain: acute and chronic. Acute pain is what you might experience when you step barefoot on an upturned plug. It provokes an unconscious physical response, and it is there to warn an organism that something is causing them damage and that they should do something about it, i.e remove their foot from the plug. In this case, pain is like any other reflex stimulus, and follows the same pathway of nerves within the body.

It is first registered by the exposed fibres of free nerve endings found mostly in skin and connective tissues, known as nociceptors. The information is then passed on in the form of an electrical impulse to the sensory neuron. The impulse then enters the Central Nervous System (CNS) and passes through the relay neuron either to the brain or the spinal cord (depending on what has caused the pain), and then back along the motor neuron to the effector muscle. The muscle receives the order telling it to contract and does so, thus moving the body and cutting off the cause of the pain. This all occurs exceptionally rapidly, and registers in our conscious minds only as a feeling of extreme physical displeasure.

|

|---|

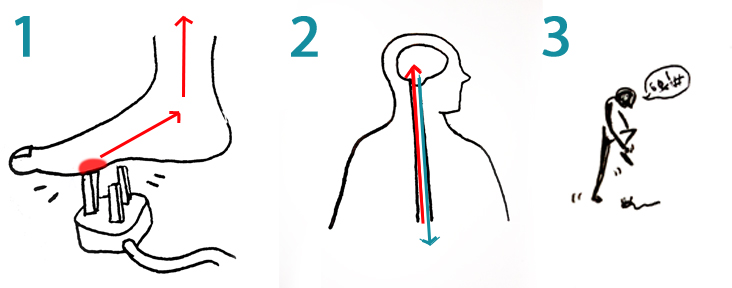

Figure 1. Acute pain

1. Stimulus is sensed by nerve cells on the skin - nociceptors. This message is sent as electrical information to the Central Nervous System via a sensory neuron.

2. The signal is passed to the brain, and then returned along the motor neuron towards the relevant muscle.

3. The impulse causes the muscle to contract, removing the painful stimulus

The importance of pain is relatively straightforward in this situation: without it, we might not realise that we were touching a hot pan, for example, and could end up causing irreversible nerve damage to our hands. However, pain often does not take this form, but rather a nagging, continued sensation informing us of an injury we already know exists. This sensation is known as chronic pain and this, rather than helping us, can stop us from being able to complete any of the behaviours necessary for survival from an evolutionary perspective; such as reproduction, feeding, and escaping from danger. Wouldn't it make more sense for the pain to only be present at the original moment of injury?

So why is pain so ever-present?

The key to this question lies in the need to modify future behavior. Despite the debilitating effects pain can have on an organism, without it there would be no stopping people from putting their lives and health in danger. People would behave with abandon, engaging in dangerous activities without having to fear the continued pain that could follow. We are already poor at safeguarding our bodies, but manage to do so mostly because we want to avoid hurting ourselves. Without pain, we would believe we were invincible. And so, although pain may make us weak, it has been crucial throughout the evolutionary timeline to teach humans and other organisms which behaviours are safe and which aren't. The same logic goes for why both acute and chronic pain are required: acute pain only present at the moment of injury would not always be enough to ensure that the dangerous behaviour was not repeated--the person may judge that the rewards of the actions would be worth the temporary pain, and not consider the long-term health effects. The presence of lasting pain overcomes this problem.

How can we overcome pain?

We have established that pain is a key part of natural selection, and that those who take notice of and respect the meaning of pain will be those most likely to survive to reproduce and pass on their genes. However, the body also has an inbuilt mechanism for overcoming pain when it is no longer useful: endorphins.

Endorphins are peptide compounds your body releases naturally during some behaviours (eating, exercise, sex), which are associated with feelings of intense pleasure. This feeling of pleasure makes individuals more likely to repeat behaviours associated with survival or reproduction.

As well as reinforcing positive behaviours, endorphins are released as responses to stress, pain and fear. When a stimulus occurs, a section of the brain called the hypothalamus releases a hormone known as CHR (corticotroponin-releasing hormone) which tells the pituitary gland (also in the brain) to synthesise the endorphins.

Cells in the brain and spinal cord have specialised receptors, which endorphins can bind to, stopping the transmission of pain signals. Endorphins are opiates, and other opiates like morphine and heroin bind to these same receptors, causing similar effects.

It is difficult to know exactly in what way the endorphins interact with our brain receptors, since the series of knock-on effect interactions involved is extremely complex and the most we can do without harming a living subject is to study levels of endorphins in the bloodstream and use imaging technology to watch their movements in the brain. These methods are, however, enough to affirm that endorphins contribute to feelings of euphoria.

An analogy commonly used to envisage pain impulses is a "pain-gate". Painful stimuli, as we have already discussed, are said to "open" the gate, as are cognitive factors such as worrying and focusing on the pain, and entertaining emotions of depression, anxiety and stress, etc. It is thought that meditation, distraction from the pain and having a positive attitude can be used to "close" the gate: putting mind over matter.

Physical activity can be used in a similar way, because exercise puts the body under stress, stimulating an extra release of endorphins into the bloodstream as part of the "fight or flight" response. This, as we have already seen, serves to regulate one's mood and block the sensation of pain, creating a feeling of mild sedation and euphoria colloquially known as "runner's high".

No pain, no gain

Pain is--perhaps unfortunately--central to the survival and health of most conscious organisms. Despite its enfeebling and unpleasant side-effects, it ensures that we curb our more adventurous actions and modify our behaviour patterns should they bring us into danger.

Then again, pain is a product of our own bodies and minds. It is also widely believed that whilst not forgetting its lessons, we ourselves can overcome it to an extent through the right attitudes and actions. Whilst it may seem that when you're hurt, the last thing you want to do is get up and dance around, or go for a run, you could find that it will improve your mood--and reduce your suffering.

References

- Previous Giving Rail the Green Light

- Next Eight weeks as a Naked Scientist

Comments

Add a comment