It's pretty easy to get lost when you venture deep into the Jungle of  Lambusango on the Isle of Buton, just off the South East coast of Sulawesi in Indonesia - a fact that I discovered more than once and to the amusement of the local guides with whom I worked during my summer on the Island. The occasional paths all look the same, and most of them are blocked by vegetation somewhere along their length. I clearly recall the first time I crawled out of a spiky rattan plant after having stumbled head over heels into it, only to see an Indonesian man running through the thick muddy undergrowth barefoot - swinging himself around trees and jumping over rocks. But soon enough you learn how to find your way and how to stay (relatively) safe, making it easier to focus on why you are actually there.

Lambusango on the Isle of Buton, just off the South East coast of Sulawesi in Indonesia - a fact that I discovered more than once and to the amusement of the local guides with whom I worked during my summer on the Island. The occasional paths all look the same, and most of them are blocked by vegetation somewhere along their length. I clearly recall the first time I crawled out of a spiky rattan plant after having stumbled head over heels into it, only to see an Indonesian man running through the thick muddy undergrowth barefoot - swinging himself around trees and jumping over rocks. But soon enough you learn how to find your way and how to stay (relatively) safe, making it easier to focus on why you are actually there.

The purpose of my trip was to investigate the ranging behaviour of a small carnivore called a Malay civet. This species (and in particular the population I was studying) makes for a very good study model as they are the largest mammalian predator on Buton Island. As a result they have become abundant as they have little or no predation costs and much lower competition for mates and resources than their counterparts on other Islands. By investigating this population we can get a better idea of how other populations operate and what can be done to conserve other species that aren't so populous. Individuals from this species of civet are about the same size as a domestic cat but have a more elongated nose, similar to that of a possum (although they are from the Viverridae family and so aren't particularly closely related to cats or possums). They are very shy and timid, which poses a difficult problem when trying to observe their behaviour and scope out their territories. Since they can't be observed freely they need to be captured and then tracked using radio collars. This method is much easier to carry out on Buton than it would be in other locations due to the large population of Malay civets that live there. By tracking their movements we can begin to understand their population dynamics which in turn could lead to the development of investigations that may strengthen our understanding of their relationships with other individuals, their feeding strategies, and perhaps even their mating strategies.

Operation Wallacea researchers (an organisation set up in the name of Alfred Wallace to conduct research for conservation purposes) have come up with a way to capture and study these amazing animals in their own environment.

Twenty-seven large cage wire traps were placed on dry level ground and evenly distributed over their population area. They were baited with salt fish which give off a strong smell which attracts civets. The cages were left over night and checked the following morning - on average we had between one and two civets captured a day, with the highest being five and the lowest being zero. Sometimes we caught animals that weren't civets at all - over three very memorable days we caught two monitor lizards and a turtle! When civets were captured the initial plan was to put radio collars on them so that they could be tracked after their release. However, upon my arrival in Indonesia, I discovered that the equipment that I would need to track these animals was broken. As a result I had to resort to a capture-mark-recapture scheme, which is where you put ear tags on the individuals that you capture before you release them, rather than a radio collar. Once they have been released there is a chance that they will be recaptured and if so they might be caught in the same or a different trap, thereby giving information about their range of movement. This method is much less precise as it only gives a very rough estimation of an individual's home range and only provides limited information (especially if the individual is captured only once, or recaptured in the same trap it was captured in previously) As a result my investigation was entirely restructured and I set out to test the variation in recapture frequencies of individuals from different age groups.

Twenty-seven large cage wire traps were placed on dry level ground and evenly distributed over their population area. They were baited with salt fish which give off a strong smell which attracts civets. The cages were left over night and checked the following morning - on average we had between one and two civets captured a day, with the highest being five and the lowest being zero. Sometimes we caught animals that weren't civets at all - over three very memorable days we caught two monitor lizards and a turtle! When civets were captured the initial plan was to put radio collars on them so that they could be tracked after their release. However, upon my arrival in Indonesia, I discovered that the equipment that I would need to track these animals was broken. As a result I had to resort to a capture-mark-recapture scheme, which is where you put ear tags on the individuals that you capture before you release them, rather than a radio collar. Once they have been released there is a chance that they will be recaptured and if so they might be caught in the same or a different trap, thereby giving information about their range of movement. This method is much less precise as it only gives a very rough estimation of an individual's home range and only provides limited information (especially if the individual is captured only once, or recaptured in the same trap it was captured in previously) As a result my investigation was entirely restructured and I set out to test the variation in recapture frequencies of individuals from different age groups.

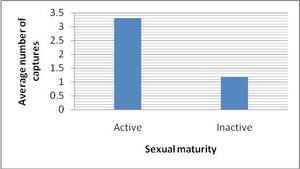

This new plan would allow me to find suggestions about whether or not civets are more curious at a particular age and whether they learn from previous trapping experiences to either like or dislike a trap. On analysis of the results it appeared that there was a significant difference in the recapture rates of individuals, but rather than this difference being connected to age it was connected to the sexual maturity (or lack of it) in an individual. It was shown that individuals who were sexually active were captured significantly more than those who were sexually inactive (see the graph).

This variation is likely to be the result of a combination of different factors. Sexually inactive individuals' home ranges have to be large enough only to provide enough food, whereas sexually active individuals are also out searching for mates. This means that sexually active individuals are more likely to be roaming farther than inactive individuals. This may hold true particularly with active males searching for females.

This variation is likely to be the result of a combination of different factors. Sexually inactive individuals' home ranges have to be large enough only to provide enough food, whereas sexually active individuals are also out searching for mates. This means that sexually active individuals are more likely to be roaming farther than inactive individuals. This may hold true particularly with active males searching for females.

Sexually inactive individuals may also still be experiencing some parental care. Mothers who are still caring for young (that may still be learning to hunt for themselves) will have to find more food so as to feed themselves and their offspring. This also holds true if the mother is still lactating as she will have to feed herself more so as to afford the higher energy costs of lactation. Immature individuals are unlikely to roam as much as fully grown adults as they have not yet learnt to hunt efficiently for themselves. Young may also be at risk from predation from other animals. While this problem is much less of an issue on Buton than it would be on larger islands (such as Borneo, where there are far more possible predator and competitors), young civets may still be at risk from large monitor lizards or wild pigs. Alternatively, decreased juvenile activity as a response to predation risk may be an evolutionary trait left over from when predation was a much more serious threat.

While trekking through the jungle day after day, covered in mud, I realised that it was much too wet for a usual dry season. This was a discovery that I made first thing one morning while emptying several litres of water out of my hammock. Sure enough this year was one of the rare occasions (occurring every five years or so) when a weather phenomenon known as El Niño took place. El Niño involves an increase in the surface temperature across the Pacific Ocean, leading to greater evaporation rates which make the air more humid and cause more rainfall. This gave me a rare opportunity to expand my project and explore the influence of rainfall on civet movements. I set out to test whether or not the surprisingly low numbers of captures that we were making was linked to the larger than usual amount of rainfall.

To do this I had to gather two other sets of data. The first was the amount of rainfall that occurred in July in the area and equivalent data sets for the month of June in 2007 and 2008. This data was easy to collect as the rainfall was measured and recorded at the nearest city. The second data set I needed was the rainfall that was occurring day to day within my trapping grid.

In order to analyse my data as I planned I had to get the capture frequency data from 2007 and 2008. This was possible because Operation Wallacea is a long-standing conservation group and its researchers have been conducting their work in the same locations for years. The monitoring of the civet population on Buton Island in Indonesia has been ongoing since 2001. This backlog of data allows different scientists to build on each other's work and provides a standardised method for setting up new investigations. When I analysed my data, I discovered that high rainfall drastically decreases the capture rates of the civets, which suggests that during periods of intense rainfall the civets are less active.

The most likely explanation is that during a rain event the efficiency of hunting decreases as prey become less active. A similar scenario was seen in Mississippi State at the Tallahala Wildlife Management Area (TWMA) with Bobcats (Lynx rufus). The Bobcats were also observed to reduce movement and activity during periods of rainfall and it was suggested that decreased hunting efficiency was the main cause of this behaviour. Not only are prey likely to be less active but they are also likely to be harder to find as rain has been shown to interfere with smell, sound and sight which are likely to be essential tools when hunting, especially when that hunting occurs nocturnally in the dark undergrowth of a rainforest.

There may also be an increased risk of injury to the civets as this quantity of rainfall may often cause flooding and the bedrock can become unstable. Mudslides and knee deep water occurred frequently in the jungle during the trapping season due to the increased rainfall. Since the terrain is not flat the water was often flowing at high speeds down rock faces which were sharp and unstable. The water was brown owing to flowing mud, which meant there was limited, if any, visibility of the ground beneath the water. Finally there may be other more specific reasons for civets to decrease their movement patterns during periods of high rainfall that are still unclear due to lack of research (with the Malay civet there are large gaps in the current knowledge about their behaviour and lifestyle).

This result has large implications for civet behaviour, as being deterred from venturing out on rainy nights will decrease their opportunities for both hunting and mating. This can be problematic especially for young civets in their first year as they are still vulnerable, and can also have a large impact on breeding rates which may influence population size. Luckily this species of civet is very populous on the Island of Buton and so the impact of a slightly reduced population size may not be difficult to recover from. However, a closely related species of civet called the Sulawesi palm civet is much rarer, having been out competed by the Malay civet in much of its native habitat. The Sulawesi palm civet is endemic to the island of Sulawesi, and remains one of the least studied mammals resulting in its actual population size being unknown. Due to estimations of population decline over the last 17 years (based on habitat destruction) the species is currently listed as Vulnerable on the IUCN red list for threatened species. If the weather has the same affect on the Sulawesi palm civet as it does on the Malay civet, the former could suffer drastic population loss.

So, all in all, my adventure in the Indonesian tropics proved both educational and fun! I got lost several times, most of my clothes got ruined thanks to the mud and spiky plants, and while the work was definitely tiring and at times frustrating it was most certainly worth it! The data I collected show that individuals belonging to this species of civet have evolved behavioural traits which make them more active when they are sexually mature and when it isn't raining. On the other hand, the collection of scratches and scars I gathered during my trip show that, much as I love the jungle, I definitely didn't evolve to live there - rain or not!

- Previous Making Metals Take the Heat

- Next Barnacles "mussel" in

Comments

Add a comment