The Power of Dreams and the Neanderthal in your Genes

In this NewsFlash, we find out how we may soon be able to predict the Asian monsoon - one of the most important weather events in the world. We explore why dreaming helps you to remember things and find out about the stresses and strains a tablet experiences after you've swallowed it! Plus, the Neanderthal in your genes - new genetic evidence that our ancestors interbred with other hominids on at least two occasions.

In this episode

00:16 - Predicting the Asian Monsoon

Predicting the Asian Monsoon

Researchers this week have presented, for the first time, a record of Asian Monsoon data stretching over 700 years. The Asian Monsoon affects nearly five billion people each year but it involves a huge weather system and it's very hard to predict how it will change each year. Until now, there's been very little climate data available on the monsoon.

Edward Cook and colleagues from Columbia University have measured tree ring data from over 300 locations and they've compiled it into what they call the 'Monsoon Data Drought Atlas,' or MADA. Published in the journal Science, they've been able to reconstruct how the monsoon varied from the end of the Medieval Warm Period, through the Little Ice Age (where Louis XIV's wine supposedly froze on his table) and during the more recent period of human-induced climate change.

Edward Cook and colleagues from Columbia University have measured tree ring data from over 300 locations and they've compiled it into what they call the 'Monsoon Data Drought Atlas,' or MADA. Published in the journal Science, they've been able to reconstruct how the monsoon varied from the end of the Medieval Warm Period, through the Little Ice Age (where Louis XIV's wine supposedly froze on his table) and during the more recent period of human-induced climate change.

The researchers plan to compare this record with others available so they could, for example, see how sea surface temperatures alter the monsoons. And occasionally, the monsoon fails completely - leading to droughts which destroy crops and cause all sorts of species devastation so finding the reasons for these events could help in their prediction in the near future.

01:35 - Sleep on it – and dream about it – to remember it

Sleep on it – and dream about it – to remember it

Have you ever found that the advice to "sleep on it" turns out to be true, whether it's solving a problem or trying to learn something? We've known for some time that sleep helps us to remember things, by helping the brain to file away and strengthen memories. Now new research from Erin Wamsley at Harvard Medical School, published in the journal Current Biology, provides more evidence that the best way to remember something is, indeed, to sleep on it - and, more importantly, to dream about it.

Wamsley and her team asked 99 volunteers to memorise the layout of a complicated computer-based maze. Then they were tested to see if they could get to a specific place in the maze after being dropped at a random starting point. Five hours later, the volunteers were tested again. But in the intervening time, some of them had been to sleep while some of them had stayed awake.

The scientists found that people who had an hour and a half shut-eye in between tests managed to get through the maze and average of around 3 minutes faster than the first time, while the people who'd stayed awake only managed to navigate it a mere 26 seconds faster.

As well as seeing whether the volunteers had had a cheeky nap, Wamsley also asked the nappers whether they dreamed about the maze. She found that people who had dreamed about doing the task during their nap improved in the second test far more than people who didn't. So it suggests that dreaming is a powerful form of mental 'rehearsal' for a task.

In Wamsley's experiments, her volunteers also had some pretty wacky dreams. For example, when the volunteers described their dreams, they didn't talk about specific things in the maze, such as certain points or router. But some of them did mention similar but related situations, such as different mazes, or being stuck in a cave.

And , intriguingly, they found that people who found the maze task most difficult were more likely to dream about it. So maybe their brains were more likely to be processing the information about the task - or worrying about the upcoming re-test - while they napped.

It's important to point out that the researchers don't think that the actual dreams themselves improve our memory - they're more like a side effect of the underlying brain 'filing' process that goes on while we sleep. But based on this research, you might draw the conclusion that it's best to study right before you go to sleep. Or, alternatively, this is a brilliant way to justify having a nap after a hard revision session.

04:31 - Following the squeeze on pills

Following the squeeze on pills

This week researchers in an international team from Switzerland, the Czech Republic and the US have managed to measure the forces felt by a small pill as it travels through the intestines.

Bryan Laulicht and colleagues developed a technique using a dummy, magnetic pill. This was fed to both human and dogs and they tracked its progress using an array of magnetic field sensors held over the abdomen. Publishing in PNAs this week, not only could they detect the direction of gastric forces exerted on the pill but also the magnitude of those forces. And they could see how these changed through the stages of digestion.

Bryan Laulicht and colleagues developed a technique using a dummy, magnetic pill. This was fed to both human and dogs and they tracked its progress using an array of magnetic field sensors held over the abdomen. Publishing in PNAs this week, not only could they detect the direction of gastric forces exerted on the pill but also the magnitude of those forces. And they could see how these changed through the stages of digestion.

They found that on a full stomach both humans and dogs exerted similar gastric forces on the pill. But when both volunteers were fasted the dogs' innards exerted, on average, five times the force of the humans'. So we now know that dogs' gastric system is only similar to that of humans after they've been fed.

But this research is important because, in order to make tablets as effective as possible, we need to know how long they can last for inside the gut. For some pills, at least, the longer they last inside you the more effective they are at delivering their medicine. So the researchers hope that by modelling the gut forces in this way they can design much more sophisticated pills than those currently on the market.

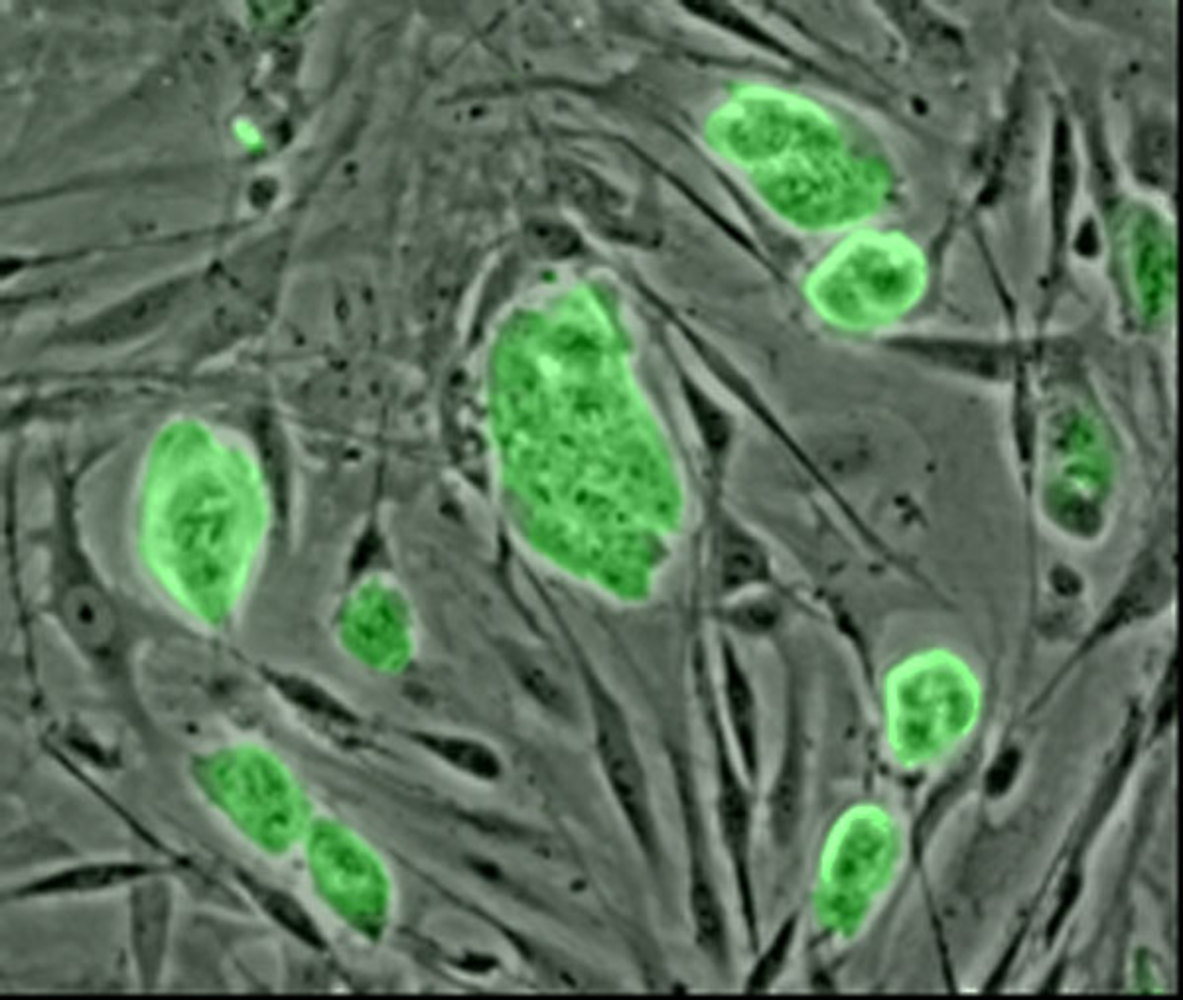

06:11 - Stretching the limits of stem cells

Stretching the limits of stem cells

Stem cells research is a really exciting area of science, and one we often cover on the show. Now new research published in the journal Nature reports an important step forward in our understanding of stem cells, and how we might be able to use them in the future.

This is work from Konrad Hochedlinger at Harvard and his colleagues. They've been trying to understand the difference between cells known as pluripotent stem cells, which can make a limited number of different types of cells, and embryonic stem cells, which can be converted into all the 220 different types of cells in the body. Although these cells both have the same genes, only certain sets of genes can be used in pluripotent stem cells, limiting their potential. And cloning experiments have shown that while a single embryonic stem cell can give rise to a whole new organism, it's never been done with plurpotent stem cells.

This is work from Konrad Hochedlinger at Harvard and his colleagues. They've been trying to understand the difference between cells known as pluripotent stem cells, which can make a limited number of different types of cells, and embryonic stem cells, which can be converted into all the 220 different types of cells in the body. Although these cells both have the same genes, only certain sets of genes can be used in pluripotent stem cells, limiting their potential. And cloning experiments have shown that while a single embryonic stem cell can give rise to a whole new organism, it's never been done with plurpotent stem cells.

They compared mouse embryonic stem cells with genetically identical pluripotent stem cells, to look for key differences in the patterns of gene activity between the two. Importantly, they found that a cluster of genes on chromosome 12 were switched off in the pluripotent stem cells, but not in the embryonic stem cells. This region contains a number of genes that are important for fetal development.

The researchers looked at over 60 different pluripotent cell lines, and found the same genes switched off in the majority of them, suggesting that they are genuinely important. And when they tested whether they could generate cloned mice from the pluripotent cells, they could only make mice from the few pluripotent cells lines where the crucial genes weren't inactivated. In fact, this is thought to be the first time that this has been done using pluripotent stem cells.

This allows researchers to tell whether the cells they're dealing with have the potential to generate all different cell types, or just a limited range. This will become increasingly important in the future, as stem cell technology comes closer to medical applications - doctors will need to be able to choose the best quality stem cells for the job. And it also tells us more about how to change the properties of stem cells - depending on whether we want them to make a wide or restricted range of different cells.

09:04 - The Neanderthal in your Genes

The Neanderthal in your Genes

Professor Jeffrey Long, University of New Mexico

Diana - Also in the news this week, a new genetic analysis of nearly 2,000 people from all over the globe suggests that our ancestors interbred with Neanderthals over at least two different periods. We're joined by Professor Jeffrey Long, leader of the team at the University of New Mexico, who have reported on this finding.

Jeffrey - Good morning. What we looked at were genotypes, genetic typings, from about 600 places throughout the genome from people from about a hundred different populations throughout the world.

Diana - And what did you look at in their DNA?

Jeffrey - Well we looked at subtle variations that are sometimes called microsatellite loci or short tandem repeat loci. And these are just regions of DNA. Typically, they don't code for any products. They're sometimes called 'junk DNA' where people have small differences in the amount of DNA that they have. These are the kinds of genetic markers that are used in DNA fingerprinting and forensics and parentage testing, and a lot of routine tests these days.

Jeffrey - Well we looked at subtle variations that are sometimes called microsatellite loci or short tandem repeat loci. And these are just regions of DNA. Typically, they don't code for any products. They're sometimes called 'junk DNA' where people have small differences in the amount of DNA that they have. These are the kinds of genetic markers that are used in DNA fingerprinting and forensics and parentage testing, and a lot of routine tests these days.

Diana - So, do we know if the microsatellites actually do anything?

Jeffrey - There are a few circumstances where they do. Most notably, there's a microsatellite type of locus in the gene that is important for Huntington's disease. But there are only a couple of dozen of those where they're actually in genes that do anything. There are thousands of them throughout the genome and most of them - the vast majority of them - don't do anything.

Diana - So when you looked at these microsatellites, what sorts of genetic variations did you see?

Jeffrey - What we saw when we looked at these microsatellites is that people typically, and this is standard for genetics, have different amounts of DNA in each of these locations and they have more or less high mutation rates, by genetic standards at least. And because of that we have all of these variations and you get clustering of patterns throughout the world. And that's what we started looking at in this study. We were interested in a model that's called the serial founder effects model and with serial founder effects, what we've postulated and other groups have postulated, is that you have that original population in Africa and then a small group left Africa and populated Europe and Asia, and eventually Asia and the Oceania as well. We were interested in studying that effect.

Diana - So how did you find these clusters of variation varied geographically as well? Did they tie-in with these models?

Jeffrey - Well for the most part, what we found was that what you find outside of Africa is a subset of what you find in Africa. What you find in any region outside of Africa, say Asia, is a subset of all Africa and the like. But the thing that surprised us was that in the out of Africa group, there was a little bit more variation than the model could account for. So we found variation in Eurasians, people in the Pacific Islands, and the Americas that couldn't be accounted for by the out of Africa migration.

Diana - So you think this genetic information is coming from somewhere else?

Jeffrey - Yes. So we had to look at possibilities of where it could come from and what could account for it. Now, one of the things that our colleagues suggested to us is that it might be just by what we call gene flow which is sort of the 'boy marries girl next door' effect that goes on throughout the world where people in these different regions do occasionally mate with each other. But that couldn't account for the effect, and in retrospect, it really could not have because that sort of gene flow just spreads things around, it doesn't create or destroy variation itself. And then we eventually came to a conclusion of is it would have had to have been from, essentially, hominids that were like people that were existing in this area or at least we think that's the best explanation at this time.

Diana - So one possibility would be Neanderthals. And if it was, what does that mean for human populations?

Jeffrey - Neanderthals are certainly a possibility but there were many different sorts of archaic people around the world before we got the modern Homo sapiens evolving. But the main implication of this is that for the last one or two decades, we really believed that once Homo sapiens evolved, they replaced all of these people around the world and didn't mate with them or incorporate any of their genes. It was a very rigid speciation event. Now what this is telling us is that our closest relatives were pretty much similar to us and it was possible to interbreed and that perhaps the speciation event wasn't quite as rigid as we thought in the past.

Diana - Indeed, well thanks very much, Jeffrey. That's Professor Jeffrey Long on the genetic evidence that most people alive today carry a little bit of Neanderthal or potentially another early human species in their genes. This work was presented at the recent meeting of the American Association of Physical Anthropologists' Annual Meeting in Albuquerque, New Mexico.

Related Content

- Previous Can you carbon date your granny?

- Next Riding in a Comet's Wake

Comments

Add a comment