Rats being tickled, a visit to the laughter clinic, and a toddler's favourite joke. We uncover the brain basis of funny!

In this episode

Why do we laugh?

Hannah - We've hopefully all enjoyed a giggle or two during our lifetimes, but how we express what's tickled our fancy varies. Some people let out hearty bellows, some chuckle and shake their shoulders with mirth, whilst others laugh silently inside. And what we find funny may differ too. Smut makes some smile, others love a good prank or pun, and some just laugh loudly at it all.

We've had a lot of questions in from you about laughter and why, and how humour evolves. And to answer some of your questions, I caught up with Professor Sophie Scott from University College London. First up, she tackles this... Steven - Hi, Naked Scientists. Steven here, regular listener, love the show. I'm wondering, why do we laugh? I know that we laugh as we find something funny, but what are the underlying reasons? Has this ability to laugh made an impact on the survival of the human race?

Sophie - If you ask humans, "What makes you laugh?" They will talk about jokes and will talk about humour. If you look at when we laugh then we laugh when we're with other people. We laugh when we're with our friends. So, you're 30 times more likely to laugh if you're with somebody than if you're on your own and you'll laugh more if you like those people, or if you want them to like you.

Actually, if you look at laughter from that sort of social perspective, it's exactly the same in us as in chimpanzees, as in rats. It's a basically old mammal behaviour for facilitating social bonds, maintaining them and sort of insuring that groups of people cohere together by laughing together. They have a tremendous advantage for us. Think it's about comedy and actually, laughter is mostly about social bonds and who we like. We laugh with the people we like.

Do other animals laugh?

We put this question to Professor Sophie Scott from University College London....

Sophie - Well, they seem to. Wherever you find laughter, it has very similar properties. You find it associated with tickling and you find it associated with play. In fact, there was a really nice work done with rats working on rat's vocalisations and get the sounds that they made when they were distressed. To do this, what you have to do is record the rats and transducer the sound down in a pitch that we can hear it because rats are so much smaller than us and they make their high pitch sounds. We can't hear them. So, they noticed, once they've done this, that the rats made other sounds. For example, when the rats were playing with each other and rats are very social animals. When they play with each other, they made a different sound and they want to know if that was something like laughter, so they started tickling them and they noticed that the rats made the same sound when they're tickled. In fact, if the rat tickled and tickled the same rat every day, the rat will start making that sound when they see you. It just that sort of, you know, you've got that kind of - if you've ever been with children, you're sort of playing with children, you get that sort of tickling thing and they'll start laughing even if they think you're going to do it. It's going to get that sort of quality to it. It's like the relationship with play. Your relationship with play is very interesting because wherever you find play, you find laughter. And play is another very basic mammal behaviour. You find it across all mammals. It's a sign. If you just watch a group of children playing, it's a sign that they are playing, that they'll make these laughter sounds to indicate this is all a game. So, I think there's probably a lot more laughter out there amongst other mammals certainly, maybe other animals as well. And we'll just go ahead looking for it.

Hannah - Can you demonstrate what kind of noise the rat or the mouse laughter is if you convert it with something that a human ear can hear?

Sophie - It sounds to us like a sort of chirrupy chirp.

[sound]

Sophie - It doesn't sound like laughter whereas you heard a chimpanzee laugh, you would think that sounds like laughter so it sounds like this. It's unrecognisably like laughter.

Hannah - As in aside, do you think that laughter is something that babies learn as a child and they know that they're getting a very good reaction from adults? So, is it innate or is it a learned skill?

Sophie - I think it's probably something that will emerge whether or not those babies have experience of seeing if you're hearing it. So, there's evidence that deaf and blind babies smile and laugh, whether or not they've seen or heard somebody else doing that. What you can do is however, you can prime that and sort of encourage it. So, we know from the rats that the rats who laugh more when they're tickled as adults are the ones who were tickled abundantly in infancy. So, it's prepotent response. It's something we'll do, a behaviour we will produce whether or not we see an example of it.

But you can encourage it and one of the things that I'm very interested in is, why an adult with people who have very different experience with laughter. So, every time I talk about laughter online or in some public event or meet somebody who says, "I find things funny, but I never laugh." I'd really like to know why some people laugh at the drop of their hat while other people are much less likely to exhibit the behaviour although it doesn't affect their enjoyment of things but is not laughing. So, I'll be interested in knowing sort of how those developmental experiences feed into adult behavioural stuff around laughter.

Hannah - Thanks, Sophie and we'll be returning to Sophie later in the show to find out exactly what's going on in the brain and body during laughter.

Is fake laughter different to real laughter?

We put this question to Professor Sophie Scott from University College London.

Sophie - Well, there's two ways you can look at this. Researchers have done a study looking at people laughing. So, what happens when you're producing laughter? And what they did was they asked people to produce the laugh and go, "Hahaha" or they went and tickled them while their feet stuck out the end of the scanner to produce real laughter. Interestingly, the network in the brain looked very, very similar. You could identify a brain area called the hypothalamus. It is'sa small area that was specifically involved in the real laughter. So, what you might find is that the real laughter and imposed laughter were very similar maybe in motor terms, but there was an emotional difference and you can see they correlate with that for the real laugh. Something that we're interested in is the flip side of that which is what happens when you hear laughter. We've been looking at what happens when you listen to laughs and unbeknown to you, there's actually two different sorts of laughter in there. There's real laughter and there's posed laughter. What we find is, that your brain absolutely tells the difference between the two, whether or not you're told to listen for them. And actually, you get very interesting observations for the posed laughter because when you hear somebody laughing, and they're clearly not actually helplessly laughing, actually, that's most of the laughter you hear. When you laugh with your friends, you're not most of the time crying with laughter. So, it's an important social cue that tells you people are doing it for some reason. I think you're always trying to work out why people are laughing. That's why when you hear posed laughter, there's actually more mystery to it. Real laughter is unambiguous. Clearly, some of these are helpless mirth whereas that if you hear somebody going, "Ha, ha, ha!" "Why are they doing that? Who are they doing it for? What's the social buzz?" Your brain really wants to know more about that.

Hannah - So, your social part of your brain actually gets more activated when it hears fake laughter than when it actually hears real laughter?

Sophie - Exactly. Exactly the same brain areas that you used to work out other people's motivations and thoughts are activated more and you hear people laughing in a posed way. For the real laughter, you get lots of more auditory activation. That probably reflects the fact that real laughter, if you think back to the last time you were laughing and you could not stop laughing, you're actually producing incredibly strong pressure in your rib cage since you're forcing the air out in those laughs. It produces a set of sounds that you don't produce any other way, and you couldn't any other way. So, acoustically, real laughter has some very interesting hallmarks that I think are we get more auditory activation to it.

15:22 - What do tickles tell us about the brain?

What do tickles tell us about the brain?

with Prof Daniel Wolpert

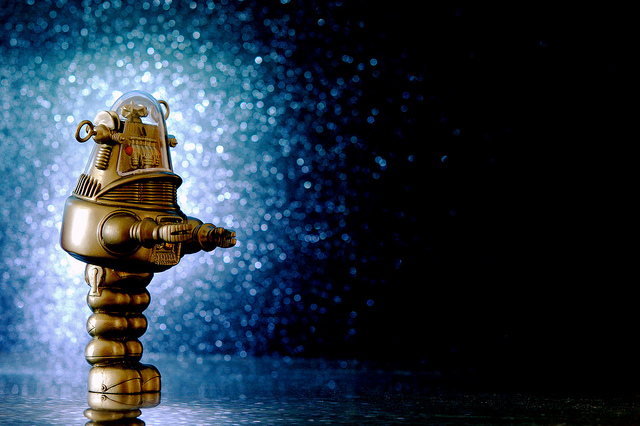

Building a tickle machine: a robot, holding a feather duster, to find out why people with schizophrenia can tickle themselves.

Now, during the show, we've been investigating laughter and one of the things that makes most of us giggle is being tickled. [Tickle recording]. The power of tickle. Now, some people are ubber ticklish whilst others don't react at all to a gentle tactile tease. What's more, it's almost impossible to tickle yourself. That is unless you have the psychiatric illness Schizophrenia. In order to investigate this, Professor Daniel Wolpert from Cambridge University built himself a tickle machine - the equivalent of a robot holding a feather duster. I met with him, firstly asking him what tickling can tell us about how our brains work.

Daniel - The reason we were interested in tickling is that it's a very nice example of how the brain does sensory processing. So, one feature you have to do when you process information that comes in through your visual system through hearing or through touch is that, some of the sensations you get are due to what you're doing with your own body. Some of it just comes about passively from things moving around in the outside world.

The fundamental thing the brain wants to determine is, what bits of the  sensory input I'm getting come from external source and what comes from what I do. Tickling is a very nice example where when you do something to yourself, it feels very different from when somebody else does. And so, there were hypotheses from '50s which suggested that perhaps tickling had to do with the fact that brain make predictions of what you were going to feel based on your own actions and remove that off. Just in the way those noise cancelling headphones work. On airplanes, they cancel off the external sounds. You hear the internal sound coming from your speakers, but the brain would have to make a prediction, rather complex prediction of what was going to happen.

sensory input I'm getting come from external source and what comes from what I do. Tickling is a very nice example where when you do something to yourself, it feels very different from when somebody else does. And so, there were hypotheses from '50s which suggested that perhaps tickling had to do with the fact that brain make predictions of what you were going to feel based on your own actions and remove that off. Just in the way those noise cancelling headphones work. On airplanes, they cancel off the external sounds. You hear the internal sound coming from your speakers, but the brain would have to make a prediction, rather complex prediction of what was going to happen.

To study this, we set up a really nice robotic interface which allow us to control the relationship to what you do and what you feel. So, you'd hold a stick in one hand attached to a robot with 3 dimensions and we could track that movement. You just control another robot which tickles you. And so, we could replicate an old '70s study where either you move them to tickle yourself or the robot will just tickle you without movement, and what we found is what we'd expect. It felt much less ticklish when you tickled yourself compared to the robot tickling you. But the really nice thing we could do is put in some different perturbations. So, we started to remove back and forward with the tickling stick and we replay to themselves in tickle mode, but with time plays of 2/10 of a second. With these very small time plays, the tickling sensation became greater and greater. By 3/10 of a second time delay, it felt like the rubber which is tickling you were much more ticklish than you were doing it yourself. So, it seemed that temporal causality was very important for cancelling off this sensation.

Hannah - And what happens in for example, Schizophrenia where people with Schizophrenia tickle themselves?

Daniel - So, there was prominent theory of some of the delusions that Schizophrenic patients have. For example, they have something called delusions of control. That means they make normal movements, but they claim their movements are being controlled by external sources. And so, this predictive phenomena can actually be used for a different thing. They need to cancel off sensory feedback, but also to determine whether the movements they're making are due to me or due to external source. So, the moment I can hear a voice speaking in this room, but I'm pretty sure it's my voice speaking in the room rather than you speaking, or my voice being played back to me. One way you can do that is I can make a prediction based on what I'm doing to my vocal tract and to my lungs or the sounds I should hear. If those match well with what I do hear, it's me doing it. On the other hand, if I hear my voice being played back, I'll realise it's not me because I won't be able to make the predictions of what I should hear. And so, one theory of delusions of control is that Schizophrenic patients can have is that they fail in terms of their prediction. They're surprised by their own movements because they didn't predict the consequences and therefore, it should be them to external sources. Consequence of this is that effectively, they don't have the predictive ability and therefore, there should have no difference in their tickle ability compared to self tickle and external tickle. Although I wasn't involved in the study, a group of patients were examined up in Edinburgh and it found exactly that they didn't show any difference in their perception of self tickle compared to external tickle.

Hannah - So, they can effectively tickle themselves.

Daniel - More likely that they can tickle themselves compared to normal people.

Hannah - What else have your tickle machine has been telling you?

Daniel - Well, based on the tickle study, we actually went on to look at some other things. So, one thing we were very interested in, I have two children who, at that time of that study were quite young. And what children on back seats of cars on long journeys, they tend to get into these fights which turns with one of them does one thing to another, the other one responds and it quickly escalates to the point at which you scream at them. My two daughters would get into these fights and often claim, both of them, the other person hit them harder. I feel as a neuroscientist, it was my job to explain because I knew my children never lie, to how they can be telling inconsistent truths. And so, we thought from the tickling study, we can partly explain why these sorts of fights tend to escalate. And that's because when you actively do something to someone else, because you generate the commands to do it, you predict the sensory feedback and subtract it off. So if one child hits another, they think they've hit the child or person less hard. So, if the other child retaliates with the same force, the first child thinks it's been escalated. So, based on that observation, we decided to run these sorts of studies and not in children hitting, but with adults and just gentle touching, in a tit for tat type game. What we found is when got people to play the tit for tat type game where one person touch another and they have to touch back with the same force, if they don't know the rules of a person that's playing and that we brief the subjects in different rooms, we find the forces they use escalate rapidly over the course of 5 or 6 turns each. If you asked the people what rule just the other person was playing by, they all things like, well, they're being asked to double it. So, we are now showing that when you generate forces on the outside world, you always tend to underestimate the forces that you're generating to this general predictive phenomena. And we think that's true not only of forces, but also in terms of speech. We always think as being quieter than we really are and so on. It's a general feature of attenuating what we believe we're doing on the outside world.

Hannah - How does this fit in with patients with Schizophrenia?

Daniel - Well, the prediction from this is a nice prediction. So, in normal subjects, when they feel a force passing, they have to reproduce it actively. They push too hard because they attenuate their own forces. Since we believe there is a failure with this predictive mechanism in patients with Schizophrenia then effectively, we predict they should be better at that task. So, if you don't attenuate it should be better at matching forces. The nice thing about that is, mostly in patient studies, you assume the patient could be worse or something and here, we have a prediction they could be better. We've tested this out in a group of patients who have Schizophrenia and age and IQ match controls. So, what we found is there's significantly better than controls in that when they experience a force passively, they have to match it actively by pushing with their finger, they do a much better job than normal subjects. Interestingly, we see quite a variety of attenuation in normal people. So, some people attenuate a lot when they produce forces, some don't attenuate very much. And we recently had a study in Cambridge where we gave people a delusional inventory questionnaire. So these are just normal undergraduates in Cambridge. Questions such as, do you ever feel you're destined for greatness? And because we're in Cambridge, many people have delusions they're destined for greatness and that's part of a delusional thinking.

Hannah - I was about to say, can you get a normal volunteer, amongst the Cambridge students?

Daniel - We get a range. The questions go from, do you ever think people are talking about you behind your back? Do you ever thought you were a zombie but no will of your own? And so, from this, we can get a measure on each subject of their delusional thinking. What we found is it strongly correlates with how much they attenuate. So, even with normal population, somehow delusional gradations of thinking correlate with how much you attenuate when you're joining these force matching tasks. Well, the more delusional you are, the less you attenuate, so the more effect you have on the world around you.

The basic experiment is very simple. People put their finger under a small leaver which is attached to a little motor and the motor generates a small force on the finger and then stops. The subject's task is to use that other hand to push another leaver from above to generate the same person. And so, what they do is they tend to push too hard because when they do it themselves, they'd predict what's going to happen subtract it off to push harder. They push harder about 50%. So if they experience a force of a kilo, they will produce 1 ½ kilos of force to get the same experience.

Hannah - So, people that are delusional, they actually have a very accurate self representation of their effect in the world around them?

Daniel - That's correct. So, people with Schizophrenia who have delusions of control, they are able to match accurately because they don't have the predictive phenomena and therefore, they can actually match more accurately than normal subjects.

Hannah - So, are they delusional?

Daniel - Well, unfortunately, yes because what it means is they find it hard to separate out with things that they've done in the world from things that just happen in the world. So, you need this predictive phenomena to be able to know, is it me or is it someone else which is doing something? And they're not able to disambiguate between those two, even though they can match forces more accurately.

Hannah - Thanks to Daniel Wolpert from Cambridge University. He probes delusions using tickle and tapping machines to get to grips with why people with Schizophrenia seem better equipped at tickling themselves. It's due to the problem of distinguishing whether sensations arise from one own actions or from external sources.

So, most healthy volunteers can identify sensation that they cause themselves and then discount or attenuate them. Hence, our inability to tickle ourselves.

However, some patients with Schizophrenia seem to lack the ability to attenuate the sensations arising from their own actions, which leads them to showing little difference in their perception of external and self tickle.

25:16 - How does humour develop?

How does humour develop?

with Dr Caspar Addyman, Birkbeck, London

A five year olds favourite joke and how does humour develop in babies?

And closing this month's show, how funny is this?...

Sam - I'm Sam and I'm 5 years old. What did the path say to the wall?

Hannah - I don't know. What did the path say to the wall?

Sam - I like your style.

[laughter]

Hannah - Funny, funny. Now, we've all had our favourites, usually terrible  jokes as children, but how does humour develop? How does laughter develop in the younger child? We turn to Dr. Caspar Addyman from Birkbeck University London to find out what keeps him fired up about his research.

jokes as children, but how does humour develop? How does laughter develop in the younger child? We turn to Dr. Caspar Addyman from Birkbeck University London to find out what keeps him fired up about his research.

Caspar - So, I've been a developmental psychology and studying babies for a long time and most of the time when we're doing that, we're actually making a baby bored. We show them the same thing over and over again, and then we show them something slightly different and see if they stop being bored. That's great for doing a controlled scientific study of how babies learn, but it doesn't capture the most fun thing about babies which is that, they laugh more than we do and at everything.

I was interested in seeing if this would give us a different perspective on what babies learn. So obviously, you and I laugh when we find something funny. Also, when you get the joke and that means the ability to spot that there's something slightly unusual about this joke or this situation.

And so, I wanted to see does that also apply to babies. Does what they laugh at map on to what they understand with different ages. So, we did this big internet survey. We've had 500 parents tell us about their babies so far and so far, we find two big main findings.

Firstly, that laughter does sort of follow this clear development that little moments of things that babies understand. So, dog going meow is not very funny until you understand that dogs are supposed to go woof! So, very young babies don't get that. In fact, the best way to make a 3 to 6-month old baby laugh is to just dangle them upside down because some reason that seems to be their - they may find most hilarious.

The other big thing we found and which is found in adult laughter research is that laughter isn't just about humour and jokes. It's a very social process. The bonding between mother and child is like an essential part of that very early development, the fact that babies have this amazing charisma and ability to make us laugh sort of sticks out a little bit about how laughter and humour works in adults.

If you look at a good entertaining person, there are jokes there, but it's also just that we find them a really charming and charismatic person and that we want to share in the delight that they're showing with us.

That's certainly something that we see between the mother and the baby. A baby, it starts laughing at something but then that sets everybody else laughing, and it's a very much a back and forth process and a social process.

Hannah - Thanks to Dr. Caspar Addyman from Birkbeck London.

- Previous Ravishing rubber

- Next Why is space dark?

Comments

Add a comment