Drugs: Time for a Change?

100 years since the first UK drug law, we explore the controversial and confusing science behind the drugs debate. From the brain basis of addiction to how ecstasy could treat anxiety, what are the implications of the world's war on drugs?

In this episode

01:41 - What are drugs?

What are drugs?

with Dr Suzi Gage, University of Bristol

What actually makes a chemical substance qualify as a drug, and why are some legal and others banned? Connie Orbach asked drug researcher and presenter of the podcast "Say why to drugs" Dr Suzi Gage to take her through the basics...

legal and others banned? Connie Orbach asked drug researcher and presenter of the podcast "Say why to drugs" Dr Suzi Gage to take her through the basics...

Suzi - The World Health Organisation defines psychoactive substances as substances that affect mental processes, for example, cognition or affect, so they affect your ability to think or your mood.

Connie - How about legal drugs? There's lots and lots of legal drugs which, I'm assuming, affect your brain, things for depression and anxiety, where do they fit into all of of this?

Suzi - Well, there are plenty of legal drugs that are used recreationally, so tobacco, alcohol and caffeine, they're all psychoactive substances. They're all legal although regulated to a certain extent, perhaps not caffeine, but certainly alcohol and cigarettes, but they do have these psychoactive effects as well.

Connie - When we're talking about the difference between legal and recreational drugs it's based on policy and where a line falls?

Suzi - Oh, in terms of the legality - yes, it's partly evidence based as a lot of it's to do with the history in the particular country. So like certain drugs are legal in some countries and not legal in other countries, for example. It's not as simple as saying these drugs are legal because of this and these drugs are illegal because of that. The sort of blurring of the boundaries makes it really quite a difficult things to quantify.

Connie - And when thinking of harm or possible good as well, that's not necessarily as fine a line of: these one are legal and they will do you good and these ones are illegal and they will do you harm?

Suzi - Yes, absolutely. I mean two substances that are the most harmful at a population level in the UK are, most certainly, tobacco and alcohol. And this may be because they're legal and much more widely used than some other recreational substances, but it could also be, and it certainly seems like it might be, that they they are particularly dangerous.

Connie - So that's really surprising when we think about how I might come across drugs I would just be like well, I'm allowed that one, it can't be that bad for me.

Suzi - Absolutely! It's very misleading for someone trying to make informed choices about what they put into themselves.

Connie - Yes. And when we talk about informed choices and what they put into themselves, how do some of these drugs, specifically the illegal recreational drugs, how are they working in the brain? Are they all doing the same thing?

Suze - No, they're definitely not all doing the same thing. There are lots of different types of recreational drugs. So some are stimulants and they'll increase the bodily function, so they'll raise heart rate, they'll raise blood pressure, they might speed up metabolism, that sort of thing. Some are depressants and so have the opposite effect, or analgesics have a sort of pain killing effect. Some are psychedelics, some have a kind of perception altering effect. And so they all work on the brain in different ways but, for the most part, this is due to their impact on neurotransmitters in the brain, so the things that get messages between neurons. And there are various different neurotransmitters and neurotransmitter circuits in the brain and so some drugs will affect some of them and some will affect others. Some will augment the processes of neurotransmission, some will inhibit the processes of neutotrasnission. So they all have quite different effects but, ultimately, they're all affecting, for the most part, these neurotransmitters.

Connie - So these neurotransmitters act as messengers carrying information from one brain cell, or neuron, to the next, and when they get there they match up with their complementary receptor, a bit like pieces of a puzzle. But what's really interesting here is that drug molecules can hijack the system and pretend to be natural neurotransmitters. This works because many of them just happen to be the perfect shape to fit with specific receptors...

Suzi - We have a system in the brain called the endocannabinoid system and, surprising, enough, certain sort of molecules or substances in cannabis, by entering the endocannabinoid system - who'd have thought. Why we developed this in our brains is maybe up for debate, but we've got nicotine receptors in our brain, opioids and that kind of thing, these are systems that are in our brain already.

Connie - How certain drugs came to fit so perfectly with receptors in our brain is, certainly, a bit of a puzzle. We do produce natural molecules that also fit to these receptors, so some people have put it down to coincidence, but there are also theories that maybe something else was going on.

Suzi - Well, it's certainly the case that humans have been using drugs for an extremely long time, or certainly the historical evidence seems to back that up as well as the suggestion that our brains seem particularly able to respond to these kinds of substances, and you can see evolutionarily why it might be advantages. Like if you were chewing on a leaf and it just helps you concentrate that little bit more, maybe you're more likely to have a successful and hunt and you're more likely to eat that night.

06:45 - Why cannabis gets you stoned

Why cannabis gets you stoned

with Khalil Thirlaway, University of Nottingham

Khalil Thirlaway gives an account of how marijuana can get you stoned.

Khalil - Weed, pot, skunk. Whatever you call it cannabis is one of the most commonly used drugs in the word. It's made from the leaves and buds of the marijuana plant and is either smoked or baked into foods and consumed. Each bud and leaf of the marijuana plant is composed of hundreds of chemicals, but there are two important ones: tetrahydrocannabinol or THC and cannabidiol or CBD. While CBD contributes to making the smoker relaxed, THC is to blame for its psychoactive effects or 'high.'

Every time someone smokes or eats cannabis, THC seeps through the bloodstream to the brain and attaches to cannabinoid receptors. These cannabinoid receptors are part of the brain's makeup and THC is very similar to a naturally occurring chemical called anandamide which usually binds to these receptors. THC floods your brain in much higher concentrations than the naturally occurring anandamide and causes the neurons that make up your brain to fire continuously upsetting the normal balance of your brain

So, how does a bit of excess firing cause the user to get 'stoned'? Well, cannabinoid receptors are prolific things and found all over the brain. This means that THC can impact on lots of different functions, from memory and hunger to pain and forward planning, giving all those well known effects like the 'munchies' and lack of motivation. Crucially, cannabinoid receptors are also present on the brain's reward system boosting dopamine and causing euphoria and relaxation. The activation of this reward system is thought to be the common factor in all drugs of abuse.

Marijuana is not a totally harmless herb but, with THC, there is no such thing as a fatal overdose. A study on monkeys reported that a person can gobble up to 70 grams of the drug, about 5,000 times more than you needed to get 'high' and still have no toxic effects. Still, if you wanted to eat your weight in weed infused treats, you might experience fragmentary thought, lack of concentration,impaired memory, drowsiness, and anxiety. Not to mention dry mouth, red eyes, and increased appetite and heart rate. Long term use has been linked to schizophrenia and memory loss, although a clear cause and effect link is yet to be found.

While it's true that some cannabis-derived drugs have shown promise in treating anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, epilepsy and neuropathic pain, the overall effect of marijuana on brain chemistry isn't crystal clear and much evidence is still awaiting confirmation in clinical trials.

09:30 - A short history of getting high

A short history of getting high

with Mike Jay, Author

Mind altering substances have long been part of cultures all over the world - so  when did our love-affair with these substances begin? Georgia Mills spoke to historian and writer Mike Jay, for a trip through history.

when did our love-affair with these substances begin? Georgia Mills spoke to historian and writer Mike Jay, for a trip through history.

Mike - It's hard to say when people first started taking drugs because it goes way back before recorded history

It seems very likely that taking drugs was something we were doing before we were 'human.' If you look at animals, there are lots of animals that take drugs for medical reasons; they turn poisonous grass to kill intestinal parasites, for example, but there are also lots of animals who seek out intoxicating drugs. Cats for example, chewing catnip, birds or elephants who will go long distances to seek out fermented rotting fruit and eat it in large quantities and get drunk. And when you get closer to humans, apes and monkeys for example, use all kinds of drugs in the wild so it's highly likely, I think, that this was something we were doing before we became human and that would explain why pretty much every human culture, throughout history and around the world, has used intoxicating drugs in some form.

Georgia - When did the first archaeological evidence for drug use start to appear?

Mike - There's archaeological evidence for the use of drugs going back thousands of years. In the Americas, for example, there are dried quids of chewed coca leaves containing cocaine which seem to go back several thousand years, maybe ten thousand years. By about four thousand years ago, you're starting to find artifacts like pipes made out of hollowed out animal bones, which have residues of intoxicating plants and seeds in them. And in the old world, in Europe and Asia, the oldest evidence is for the use of opium, opium heads, and dried poppy heads. And then, at the very beginning of writing, Egyptian pipari, medical pipari like the Edus piparus, record the use of drugs. Then, when you get to the classical era, great literature, people like Diaz Scorsese writes about plants and drugs and pharmacy in great detail

Georgia - What clear is that people have been indulging for years - and for many different reasons. There's evidence people used them in spiritual and religious ceremonies, medically, and, much like today - to help stay awake or for social situations. The first evidence of advising against drug use came from ancient Egypt in 2000 BC, when priest, wrote to his pupil: "I, thy superior, forbid thee to go to the taverns. Thou art degraded like beasts.' But these kind of warnings haven't stopped drugs from spreading across the world.

Mike - The sort of global drug trade that we have now started really about 500 years ago, around the time of Columbus. If you go back before then you'd find a world where, in say Thailand or Malaysia, people are chewing beetle nut, and in the Andes they're chewing coca leaves, and in different parts of the world people are taking different things.

What you get from that point on is the beginning of global trade and is around the kinds of substances that we don't quite think of as drugs any more, but things like tobacco, and sugar, and tea, and coffee. The global network that emerged after the discovery of the Americas, about 500 years ago, you start to see these kinds of items traded, particularly things like tobacco and sugar that really made up the first layer of what we now regard as global trading routes.

Georgia - During the 19th century, scientists started extracting pure chemicals forms of chemicals from the natural drug. Cocoa leaf to cocaine. Opium to morphine. These drugs were seen as not luxuries or bad habits but medicine - It sounds bizarre, but you could go and get morphine from the local pharmacy. Cocaine was an ingredient in Coca-Cola until 1903. But slowly, it became clearer that these drugs could do some serious damage....

Mike - People started to realise by the mid-19th century when drugs were being used quite widely that substances like opium were dangerous; it was very easy to overdose on them. It was the same time that people started to be concerned about alcohol and the health consequences of alcohol, which led to the temperance movement and, eventually, to alcohol prohibition.

So, from about the mid-19th century, you start to get, initially, regulation like the Pharmacy Act in Britain in 1868, which stipulated that certain certain poisonous substances, including opium, could only be sold by registered dealers and so on. So that was the way in which drug use was controlled until pretty much exactly 100 years ago during the First World War in the Defence of the Realm Act. It was the first time Britain that substances like morphine and cocaine were prohibited from open sale and by that time you had, in the United States, the Harrison Act of 1914 which was an act that controlled the supply of narcotics. So the actual drugs as illegal banned substances - that story is about 100 years old now.

15:48 - The truth about heroin

The truth about heroin

with Khalil Thirlaway, University of Nottingham

Khalil Thirlaway takes us to the brain, to explore what actually happens when you  take heroin.

take heroin.

Khalil - Heroin, like morphine, is an opiate synthesised from the pods of a poppy plant. Although heroin's godfather though he was creating a safer form of morphine for pain relief, he accidentally synthesised an even riskier molecule and named it heroin for the feelings of heroin instilled in the user. But, within a few years, after being marketed and sold as a medicine for conditions like insomnia, heroin was found to be two to three times more potent than morphine and also, way, way more addictive.

Heroin, also known as horse, smack or junk works in different ways. Part of it works as a stimulant which means it speeds up your brain, but a greater portion is a sedative or depressant which slows you down. Whether it's injected smoked or snorted it quickly enters the brain where it's turned back into morphine and binds to proteins called opioid receptors. These are found in areas of the brain associated with pain, reward, and also in the brainstem which regulates automatic processes like breathing. After docking onto the brain cells, heroin triggers the release of 'happy hormone' dopamine, up to the ten times more than normal which produces feelings of intense euphoria, relaxation, fearlessness and tolerance to pain. Yet heroin and other opioids don't suppress the pain itself, rather they change the subjected experience of pain. This is why people receiving these drugs for pain relief say they still feel the discomfort, but it doesn't bother them anymore.

After more and more exposure to opioids like heroin, users begin to build up a tolerance to these flash floods of dopamine and need more and more of the drug to create the same effect. Heroin can also cause pain systems to go into overdrive once the dose has worn off, meaning the drug is needed just to feel normal. Going without a fix can cause withdrawal symptoms like nausea, cramps, anxiety, fever, and diarrhea. Long term, heroin wastes the brain, causing damage to areas of the brain associated with memory, decision making and complex thought.

One of the leading causes of death in users is to simply stop breathing due to the depressive qualities of the drug on the brain stem. In fact, according to a report from the European Monitoring Centre on Drugs and Drug Addiction, opiates, mainly heroin, were involved in four out of every five drug related deaths in Euro

18:08 - Addiction: My path to recovery

Addiction: My path to recovery

with Liam Farrell, Writer

Heroin is part of a group of drugs called opiates. These all act in a similar way  and are all very, very addictive. Liam Farrell is a writer and retired doctor with first-hand knowledge of the overwhelming power of addiction, and he described his experience to Connie Orbach.

and are all very, very addictive. Liam Farrell is a writer and retired doctor with first-hand knowledge of the overwhelming power of addiction, and he described his experience to Connie Orbach.

Liam - Within seconds I feel a rush coming on. Firstly a tingle coming up my right arm, then a wonderful warm tidal wave stroking my whole skin - my whole body. It seems to find a centre deep within my chest. I try to savour each moment, each instant but, just as quickly as it comes, it is gone. That's it - done - all over. It lasted a few breaths at most.

I'm disappointed it's over and wish I could turn back time a few seconds. I also feel dissatisfied, a bit cheated. The rush wasn't quite as good as I hoped it would be. I wish I'd held it off for a few hours, then I'd still have the drug and the rush would been better. The drug makes me feel pleasantly languid like I'm wrapped in cotton wool. But, even at this stage, even so soon after injecting, not much more than a few minutes, reality starts to pull me back in. The modest euphoria which lingers after the rush begins to leak away.

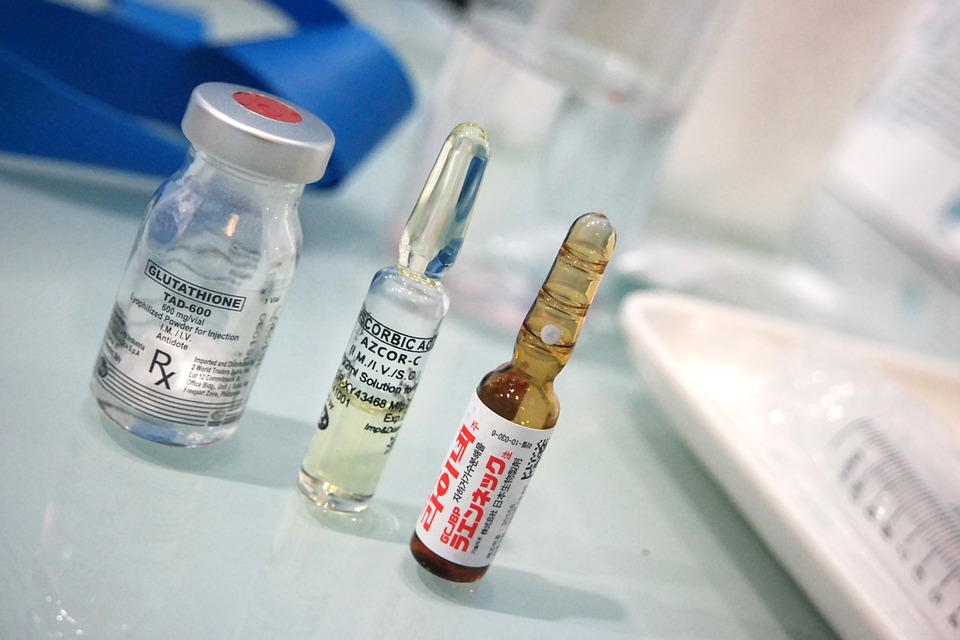

I start to worry about getting rid of the evidence. Often I miss something - the syringe wrapping, a blood stained tissue, the occasional needle. I'm also becoming more aware that was my last ampule of seclamorph. I already knew this, of course, but I had put off the evil day of facing up to it. Now there is nothing between me and drug withdrawal. I dread the next 48 hours.

My name is Liam Farrell. I'm a retired family doctor and a writer. I'm from Rostrevor in County Down in Ireland. I am a morphine addict in recovery and I've been clean for eight years and I have a very good life now because I was helped by some very good people when I really needed it.

Connie - Thank you so much for reading that Liam. That's an extract from a piece that you wrote about your own experience.

Liam - It's very hard to say how you first became addicted or how you first started using; I've asked myself that many times. But, at some stage along the line, I decided to try morphine just to see what it would be like. It's very hard to analyse why I actually made that step of doing that but, that's what happened.

Initially I would have used very infrequently; once every three to four months but then, at a certain stage, I began to use more. I remember very vividly one Sunday afternoon when I was feeling really tired and exhausted and not really knowing why, and I took a small amount of diamorphine and suddenly I felt normal. It was like a hammer blow to realise I was physically addicted to morphine at that stage.

Connie - Can you explain to me, as best you can, what withdrawal is really like? I imagine it's kind of impossible to explain to the intensity to which you feel, which why it's so hard for anyone to understand but yes, it would be interesting to hear your take on it.

Liam - In a very essentially physiological way. it's like your body is suddenly flooded with noradrenaline - the fight or flight hormone, but yet there's no reason for it. It's like all the other pleasant symptoms of taking morphine as you go into reverse, instead of feeling languid and comfortable you feel agitated and fearful. You're cold and freezing and sweating. You get diarrhea and abdominal cramps. None of those on their own are any more severe than bad influenza, but what is really debilitating is the fear and anxiety which is associated with it. That's a memory that will stick with me forever although, theoretically, I knew in a couple of days I'd be better. When you're in that state rationale doesn't help.

The catch 22 of course is that, even though withdrawal was so distressing, it didn't stop me relapsing yet again.

Connie - Mmm. It's so interesting, and I think so hard to understand what you're saying, is that this withdrawal can be so completely horrendous and yet it's not enough - the drug is still in control.

Liam - Yes. I mean it's the power of the drug that's just amazing. One of the golden rules of Narcotics Anonymous and Alcoholics Anonymous is that the drug will always win. I'd hate to put my willpower to the test. I remember the particular colour of the cyclimorph drug that I used to use is blue and red, and that's just a key for me. If there's a pack of cyclimorph lying in the road half a mile away I would probably pick it out. It's umm..... sorry.

Connie - That's alright. You've been clean now for eight years and it seems clean is never completely free but what's it feel like now? Do you feel like this is part of your past?

Liam - Well it's always going to be a pivotal part of my life that I am an addict. I wake up every morning and say whatever happens I'm going to stay clean today and then, when I go to bed at night, I say well whatever happened I didn't use today. They're small elements of self-discipline which I'd forgotten when I had a relapse in 2008. At the same time it doesn't define me. I've many other parts of my personality and life which are equally important: I'm a husband, a father. I have good friends, I'm involved in music, I'm involved in writing. I'm very active in social media. And these are all different parts of my life which aren't affected but, having said that, addiction was a very pivotal experience.

And one thing it does make is I'm full of gratitude that I did get a second chance. That people that cared for me did stick by me when I needed them. That when I needed help I met good people that were willing to help me and it does make me appreciate the good times of life even more. It also made me a better doctor. My own frailty had been so starkly revealed that made me more understanding of frailty in others.

Connie - Mmm. So for you, your main message from this is yes, this is something that you won't ever completely get away from but there is life after addiction - there is a way out there is something else?

Liam - Yes. There is such a thing as redemption, you can get better, there is help, there are good people out there who will help you.

If you, or someone you know has a problem and you want to talk, Liam can be reached through twitter on @DrLFarrell

25:59 - How drugs can hijack the brain

How drugs can hijack the brain

with Dr David Belin, The University of Cambridge

Addiction is a huge problem and it's very difficult to get exact statistics - but  estimates from the National Drug Evidence Centre put it in the hundreds of thousands in the UK alone. There's clearly something quite drastic going on in the brain to cause this, and new research from the University of Cambridge might just hold the key, as David Belin explained to Georgia Mills.

estimates from the National Drug Evidence Centre put it in the hundreds of thousands in the UK alone. There's clearly something quite drastic going on in the brain to cause this, and new research from the University of Cambridge might just hold the key, as David Belin explained to Georgia Mills.

David - So addiction is a state. It's a psychiatric disorder characterised by loss of control over habitual drug-seeking behaviour in such a way that people continue searching for drugs, and consuming drugs, despite awareness of negative consequences of doing so.

Georgia - And which drugs do we think of when we think of addiction?

David - Often people tend to think about illegal drugs such as cocaine, heroin but, actually, alcohol and tobacco are highly addictive as well.

Georgia - And how have you been investigating this?

David - We are interested in understanding why only some individuals who are exposed to these drugs will eventually lose control over their consumption. Because clearly, there's an interaction between something in the brain before you start taking drugs and the effects of these drugs that would eventually make you vulnerable to addiction and you would develop the disorder. And we try to understand it using both clinical and preclinical approaches, and for this we have the help of little rats that are very clever animals and, interestingly, in humans not all of them if they are given access to drugs would eventually develop addiction.

Connie - So let me get this right Georgia - not everyone forms addiction to these drugs?

Georgia - No - in fact rats, just like humans, have about a 20% chance of become addicted to cocaine.

Connie - So are they giving cocaine to the rats then?

Georgia - Yes they did actually - they allowed them to have small these small amounts they could take freely. But after a while, they would start making them work harder and harder for their next dose. So they'd get them to press a lever once, twice, 10 times, 500 times. And after a certain point most rats decide that actually, the drug is not worth the effort.

But 20%, the 20% that are addicted keep pushing and pushing and pushing the lever, up to 10,000 times to get their next hit.

David - They just can't stop! And they are sweaty, they put everything they've got into pressing this lever to get to the next fix and these rats clearly are addicted.

Georgia - Well that's quite a powerful image there! Did you find out out why some rats were more likely to get addicted than others?

David - We've identified a couple of behavioural traits such as novelty-seeking and impulsivity that predicted this vulnerability to switch from volitional to compulsive cocaine-taking behaviour. So impulsivity, for instance, the example I tend to give my students all the time is, if during one of my lectures - if Chuck Norris is in the room and he stands up and says 'Oh you know I don't really like your lecture', and I actually engage a fight with him because I'm frustrated, this would be very impulsive, because the consequences would be harmful and then I would regret it. So this is what impulsivity is.

And we've actually identified this trait in cohorts of animals. Three years after we made this discovery, the same vulnerability trait was identified in humans, so that was a kind of success story.

Georgia - Being more impulsive and novelty-seeking - those are traits identified that makes both rats and humans - you mentioned switched from an adaptive seeking of cocaine to a compulsive one. What is changing in the brain to make this change?

David - Initially volitional drug seeking and taking behaviour depends upon psychological mechanisms which require a pre-existing representation of the outcome. So when you and I work, and we work because we know, for instance, on Friday we may go out to the pub. We have this representation of what we're going to do with the money we've just earnt. When the behaviour become habitual, then the behaviour is subdued, subjected to stimuli in the environment, and stimuli triggers specific behavioural features outside your awareness.

So a good example in your everyday life is, if you go back home tonight and it's dark. What are you going to do? You open your door and then you try to reach the switch and switch on the light. And what if in the morning before you left, the light bulb was broken? When you get back home this is exactly what you would do nevertheless. You would try to switch on the light and then say, oh yes it's broken - this is a habit. And this is exactly what drugs do, they hijack this system and they push the system towards drug seeking becoming habitual. So now every single time you are presented with a cue that you have experienced when you were taking drugs or seeking drugs, all these kinds of cues are going to trigger behavioural repertoire which actually has been designed so that you would get the drug, and you are not aware of what's going on. This is what a habit is. So there is a clear transition psychologically in what's going on.

Connie - So David's arguing that you kind of go into autopilot, trying to get the next hit.

Georgia - Yeah exactly, and they've actually found evidence for this inside the brain. When animals start taking drugs, many parts of the brain are involved, including the pre-frontal cortex which is very closely associated with decision making and control.

But, what happens in addicts is, after a few months the system kind of changes and switches to another area in the brain which we associate with habit, but it completely circumnavigates the prefrontal cortex.

Connie - The area involved in control and decision making?

Georgia - Yes, it forms a kind of backdoor in the brain skipping past your willpower centre implying that it just doesn't come into it. Which David argues means we should look at addiction in a very different way...

David - Addiction should be considered exactly as schizophrenia or diabetes. It's a chronic disorder and it's not merely a question of willpower. If you suffer from it then there's very little you can do yourself about it and, unfortunately, there are very few effective treatments for drug addiction. There's none for cocaine, for instance, for cocaine addiction.

In terms of social implications, I think it is time to consider drug addicts really as patients and not as criminals. It's not because they want to harm anyone that they may actually go and sell their grandma to get a couple of quid to buy a line. It's because they have to because of their disorder. And, as long as they aren't considered at patients, socially there would be something wrong with the way we handle drug addiction.

Connie - How does this finding correspond to actual therapies ?

Georgia - This work does suggest some new drug candidates and treatment avenues to explore but it's still very much a 'watch this space.'

The effects of ecstasy

with Khalil Thirlaway, The University of Nottingham

In the next in our series on drugs 101 Khalil Thirlaway explores ecstasy...

Khalil - Since ecstasy's actual name is a bit of mouthful (methylenedioxyamphetamine), this drug goes by many street names like E, MDMA, Adam, Mandy, X, or Molly. Ecstasy was first created just before the First World War as a base compound for other drugs. After being tested in the US army, and even used as a therapeutic drug, ecstasy slowly rose to fame as one of the most popular party drugs of the 1980s.

When a partygoer swallows the drug it's rapidly absorbed in the gut and then converted to its active form in the liver. It then travels to the heart and is eventually pumped all the way to your brain. Upon reaching the central nervous system it triggers a load of electrochemical firing and powers up some key chemicals, among them dopamine and serotonin. This change creates intense happiness, increases sociability and empathy, and an inability to sleep.

These feelings generally last around three to five hours as your brain naturally reabsorbs the serotonin and breaks it down. But because ecstasy releases so much serotonin, your body's response goes into overdrive, meaning that when the drug has worn off, there's less serotonin available to bind to the receptors and maintain a normal level of happiness.

These low levels of serotonin bring on a short-lived period of depression for days after use - often called a comedown, but depression is not the only side effect. Ecstasy can lead to other unpleasant sensations like irritability and tiredness, along with physical traits like nausea, jaw clenching, blurred vision, muscle cramping, and even a rise in body temperature.

People who overdose on the drug may lose consciousness, and have seizures, hallucinations, even organ failure. But it's at it's most dangerous when it's cut with other cheaper substances like bleach somewhere along the production line, which can be fatal.

Connie - Khalil mentioned some side effects there, but what's common in a lot of these drugs is that we really don't know what they do long term, especially as it's so hard to do clinical trials. So even if a drug doesn't seem that dangerous in the short term, it could still affect you further down the line.

35:38 - Should we decriminalise drugs?

Should we decriminalise drugs?

with Ed Morrow, The Royal Society for Public Health

Around the world there are some very different approaches aiming to reduce drug harm, from legalisation, to the death penalty. So where does the science stand? The UK's Royal Society for Public Health, or RSPH, recently released a report calling for a change in how the war on drugs is fought. Georgia Mills spoke to Ed Morrow, campaigns officer at the RSPH.

harm, from legalisation, to the death penalty. So where does the science stand? The UK's Royal Society for Public Health, or RSPH, recently released a report calling for a change in how the war on drugs is fought. Georgia Mills spoke to Ed Morrow, campaigns officer at the RSPH.

Ed - The 'taking a new line on drugs' report is really the first time that a major public health organisation in this country has come out with a strong line on how drugs policy in this country needs to undergo a major shift. Previously we have been too focused on the criminal justice approach, which is just not working in terms of reducing harms from drugs.

We've seen a situation over the past decade where yes, although use of some of the less harmful drugs, such as cannabis, has continued to go down slightly, actually, use of some of the most harmful substances, things like heroin, has risen slightly and, more importantly, the harm associated with those drugs. Particularly the number of deaths associated with them has risen significantly, so we are not tackling that harm coming from drugs. So what we've set out in this report is a new public health based approach which is focused on reducing the harm from drugs

Georgia - How would you go about doing this?

Ed - So, one of the major pillars which underlies it is the idea of decriminalising possession and use of drugs. That is not the same as full legalisation, but we've been seeing for a long time that criminalising people who have a drug misuse problem does not does not help them get better. It puts a lot more costs onto society in the long run and it also discourages people who have a drug misuse problem from coming forward for the treatment they need because they are scared of being prosecuted. So that's one of the first major steps we need to look at, and we also want to see much better, more universal drug education for young people.

Georgia - Where does the scientific evidence for these arguments lie?

Ed - Well, we've been looking a lot at international examples of different countries that have tried similar approaches to what we are suggesting. One of the biggest examples we've been looking at is Portugal. Now Portugal, in 2001, decriminalised all possession and use of drugs in a similar way to what we would like to see. Now over that period they have seen a great increase in their health outcomes related to drugs. The number of deaths related to drugs misuse has plummeted, I think from round about 80 a year to round about 10 a year. Infection rates for various infections related to drug use, things like HIV and Hep C, those have also fallen through the floor. And, at the same time, drug use has not risen in the way that some people have feared and they still have a level of drug use which is well below the European average and is below what we have in this country.

Georgia - Alcohol and tobacco - two of the most commonly used drugs in this country, and they're the two legal ones. Could this not be a warning that if we do move towards this decriminalisation it might normalise the use of these drugs, maybe not immediately, but eventually lead to greater uptake?

Ed - If we again go backs to the evidence - countries that have tried this approach - the example in Portugal is a 15 year scheme now where they've had this approach and it has not seen a normalisation, it has not seen an uptake in levels of use of other drugs. So we think that what we've seen so far from other countries would disprove that fear.

Georgia - And what about evidence from UK soil, because I know that drug use is very different from county to county, let alone between countries?

Ed - Well, it is interesting to look at the different ways in which police forces in this country are dealing with various types of drug use. So some police forces in certain parts of the country , Durham are one major example, have stopped actively pursuing and prosecuting people for possession and small scale supply of cannabis and we have not seen the effect of usage going up in those areas. But it's also interesting to look at the situation with what happened with cannabis being upgraded to a Class B drug in this country, which did not lead to a fall in use. So it very much seems, even with this country, that the level of enforcement, the level of penalties, does not have a direct link with the level of use.

The resistance to making this change is not a scientific one, it's a political one because the reality we live in, at the moment, is that drugs policy, both in this country and across the world is driven by politics rather than the science and that is a situation we need to change.

Georgia - Recently legal highs have just been banned in this country. Could you explain to me how this has been done and whether you think this is a good move?

Ed - Legal highs are, or were, substances which are designed to mimic the effects of traditional legal drugs but with a slightly different chemical composition so that they would avoid the existing legislation and classification that would apply. The new Psychoactive Substances Act which has come in to ban what were formerly known as legal highs is an interesting situation. We think it's going to be quite problematic in terms of enforcement because it seeks to ban any new substance which has a psychoactive effect. And, of course, there are lots of perfectly innocuous substances which do have such an effect and, obviously, they've had to put in exceptions - alcohol and tobacco and many sorts of medicinal products as well.

Georgia - I heard the original drafting accidently banned things like paint, and perfume, and petrol?

Ed - Yes, so it's that kind of thing. They've got themselves in a bit of a mess over this, but they've brought it in now. But the interesting thing as well for us on this is that what it has done is to ban production and sale of these substances and it has not criminalised possession and use. So we think, even though this legislation is a bit of a mess in some ways, there is this inherent recognition from the government that criminalising people for drug use doesn't work. We'd like to see that situation reflected with more traditional, if you like, illegal drugs.

Connie - We asked the government for a response for the Royal Society for Public Health's report and they gave us this statement:

"This government has no intention of decriminalising drugs. The decriminalisation of drugs would not eliminate the crime committed by the illicit trade, nor would it address the harms associated with drug dependence and the misery that this can cause to families and communities. The UK's approach on drugs remains clear; we must prevent drug use in our communities and support people dependent on drugs through treatment and recovery. At the same time we have to stop the supply of illegal drugs and tackle the organised crime behind the drug trade. There has been a reduction of drug use amongst adults and young people compared with a decade ago and more people are recovering from dependency now than in 2009 and 2010."

44:06 - How acid sends you tripping

How acid sends you tripping

with Khalil Thirlaway, The University of Nottingham

Khalil Thirlaway gives us the lowdown on LSD, aka Acid.

Khalil - Think of LSD and you probably think about The Beatles' iconic movies of merging colours and floating submarines or flower power and the heady stories of 1960's San Francisco.

Acid has been the controversial inspiration to many great thinkers from Aldous Huxley to Steve Jobs but what's happening in the brain to give such life altering experiences?

The hallucinogen LSD, or lysergic acid diethylanine, was brewed almost a hundred years ago in Switzerland, and like many scientific discoveries was a bit of an accident. In fact, Albert Hofmann, had no way of knowing that his new drug (meant to stimulate blood circulation and breathing) would have a strong psychedelic effect from just the smallest of doses!

After accidentally touching a tiny crystal to his tongue, he experienced first-hand the effects his powerful hallucinogenic drug: time slowed down and he later described . "an uninterrupted stream of fantastic pictures, extraordinary shapes with intense, kaleidoscope like play of colors."

For the next couple of decades LSD led a glamorous existence as it was experimented with in science, music, literature and even used by in mind control experiments by the CIA before it was made illegal in the late 1960's.

When a person takes LSD, part of it is metabolised in the liver and eventually excreted, while the other part quickly gets to work changing things inside the brain.

It's believed that LSD interferes with serotonin, a chemical messenger that has a big role in mood, emotion and sleep patterns. Through acting on specific receptors, the drug appears to break down barriers that usually separate areas of the brain from each other, allowing vision, movement and hearing to blur together, causing hallucinations and free flow of thought, often referred to as an acid trip . One symptom, known as ego-dissolution, arises as the cells in our brain, our neurons, fail to fire together, preventing the brain from functioning in a coordinated manner. This can dissolve a person's sense of self as their own thoughts are united with the environment, resembling the brain of an infant: free and unconstrained.

But no two LSD experiences are the same and while the idea of a communion with nature may sound tempting it is hard to predict which way a trip will go. With one dose lasting up to 20 hours, and many people reporting repeat trips years later, heaven can soon turn hellish.

46:54 - Using drugs for good

Using drugs for good

with Dr George Greer, Heffter Research Institute, Dr Charles Grob, Univeristy of California Los Angeles

Research into medical uses for certain illegal drugs has been picking up pace in the past few years. But there are still a number of barriers, this means that globally the amount of work in this area is minimal. George Greer is the medical director of the Heffter Research Institute in the United States and he explained to Connie Orbach why psychedelic drug research is such an underfunded area...

the past few years. But there are still a number of barriers, this means that globally the amount of work in this area is minimal. George Greer is the medical director of the Heffter Research Institute in the United States and he explained to Connie Orbach why psychedelic drug research is such an underfunded area...

George - We there's a couple of problems: one is these drugs cannot be patented so there's no commercial interest in investment, so the drugs are too late to get a patent

Governments, with the exception of the UK, have been reluctant to fund this research, and we can all speculate why, but I assume it's because they're schedule 1 abused is part of the mindset. So that's the biggest limiting is the lack of government funding which means the lack of researchers who can expect to be funded for a career, so they have to do other research for their career path that has more stable funding.

And then being schedule 1 does create more expense by having to go through more hoops because of the drug enforcement agencies which require security and paperwork and that sort of thing. So that's an inhibition too and just the stigma that people think these drugs are bad. So there's a lot to overcome.

Connie - Schedule 1 is a class of drug that is deemed to have high abuse potential and no medical use. Drugs that sit in this category vary from country to country, but in the USA they are things like heroin, LSD, marijuana, MDMA, and a whole host of other obscure things.

But, by putting these substances into schedule 1, a sort of catch 22 is created. Drugs that have no medical use are under harsher restrictions making them harder to research, therefore, making it more difficult to determine any medical use for them.

This has stifled research for a long time but, luckily, things are changing...

Charles - An opportunity arose at the beginning of the early 90s to do research investigations on normal volunteers - that was the first opening.

I had the second permitted study, which was with MDMA at Harbor-UCLA Medical Centre. Once we established the feasibility, our group and other groups were able in the early 2000s to obtain regulatory approvals to conduct clinical research in a population that was presenting because of a particular psychiatric condition.

Connie - That's Charles Grob from UCLA and, despite the difficulties, he's been researching possible medical uses for section 1 drugs for years. One particular study, funded by Heffter of course, examined the potential of psilocybin, that's the thing that makes magic mushrooms so magical, to treat extreme anxiety in cancer patients.

Charles - They were provided a number of screenings and also preparatory psychotherapy sessions. They came in for two separate treatment sessions; one session was active medicine psilocybin, another session was a placebo.

We sat with them for the entire 6-8 hour psilocybin experience and afterward, we did some rather intensive integrative psychotherapy sessions to help them assimilate their experiences. And then we followed them for the next six months just examining their anxiety, their mood, other aspects of their quality of life, and we found very good results.

We found that, over time, there is a significant improvement in levels of anxiety at particular points in time. And, having got to know many of these subject quite well, we also observed that there were clear and distinct improvements in their quality of life in the time they had remaining.

Connie - And you're now working on, actually not a hallucinogenic, but MDMA or ecstasy?

Charles - Yes, MDMA is related to hallucinogens but with clearly distinctive differences and is really in a different class altogether. We've had a study going for the past two years where we've had permission to treat a population of autistic adults who have severe, and often incapacitating, social anxiety with an MDMA treatment model.

We haven't quite finished the study; we're still looking to recruit two final subjects so we haven't done our final data analysis. But just having gotten to know our subjects very well and having been in the room for all of the treatments, it's my impression that we will observe some positive results that this treatment model may have merits when utilised under optimally safe conditions.

Connie - So it sounds like what we're talking about with both the psilocybin and also this one is real changes in quality of life?

Charles - Yes, absolutely! A clear observation in all of the studies done with psilocybin and MDMA over the last 12-15 years.

Connie - So clearly things are moving on but it does may be think. I mean this sounds a bit of a faff. How feasible is it really to give controlled substances to people? Here's George again...

George - Psilocybin - it's never going to be a drug that a person is sent home with a prescription or sent home with capsules of psilocybin because they always have to use it with supervision. So, in terms of distribution it's only going to the clinics who are administering the drug. It's a big procedure, you know, that takes many meetings and none of that is because it's a schedule 1 drug, that's all because of just the effects of the drug.

Connie - But still, either way, any drug that requires this amount of supervision seems a little unfeasible..

George - Yes, but the benefits that we're seeing with one or two sessions can last for weeks or months as opposed to taking a drug every day.

Connie - I guess my other question is - if it's so difficult to study these things, if there's so little funding, for researchers there's a lot of work they have to go through - why aren't we focusing our attention on maybe pre-existing drugs for anxiety which aren't within this section 1 area?

George - Drug companies are doing that all the time; they're researching and looking for new drugs that are similar to the ones that we have on the market now. In psilocybin, because it works in a different way, it has an effect that the current drugs like them are not going to have because they all require daily use.

Connie - So given all this, so given that these drugs act in a different way that isn't actually available on the market, does it make you sad that we've potentially been sitting on these drugs for a long time and not used them as early as we could, maybe, when we knew that they could be effective?

George - Well sure. I mean, I think those of us in the field have gone through that grief process a long time ago of the loss of these decades that people could have been helped and much more could have been learned, and we're focused on going forward and doing the research which is being done now and private people are coming forward to pay for it. So I think the mood amongst the research community is very positive though recognising soberly that there are going to be frustrations and difficulties, and stops and starts, but I think people are all feeling very optimistic that this is going to start benefiting people in the next several years, certainly by 10 years. I think Europe, the US, and the UK, these will be available treatments for people.

- Previous What's it like on Mars?

- Next 40 years of selfishness

Comments

Add a comment