What is Love?

Interview with

People speak about having 'chemistry' with a partner but little is known about what actually happens in our brain when we fall in love. On Valentines Day we wanted to investigate the science behind romance. Kat Arney was joined by Dr. Alex Kogan from Cambridge University and Professor Gert J Ter Horst from the University Medical Centre in Groningen.

Kat - So Alex, in your scientific opinion, what is love?

Alex - Other than a headache you mean?

Kat - I think other than a major headache for many people.

Alex - It's a really timeless question. People have been wondering about this particular question probably since the beginning of humanity. I think my best hack at the answer would be to say that it's quite a few motivations. It's emotions. It's behaviour. I would say love is some of the best stuff in your life and some of the worst stuff in your life. And so, it's got a lot of complexities. When we think about different types of love, we've got everything from friendship love to love of a romantic partner, to love of cheesecake, and it makes studying love extremely difficult and so, as this new era of studying love from a neuroscience, a genetic perspective starts to really emerge we're trying to work out all these details and complexities.

Kat - So, forgetting the kind of love of cheesecake which I really do understand, when we talk about romantic love, the kind of love celebrated with Valentine's Day, what do we know so far about what's going on in the brain?

Alex - There has been a few studies done on this and the work is really preliminary I would say, but what we know is, when we look at a romantic partner for example compared to a stranger, we do see more activation and the dopaminergic component of the brain where a lot of the reward aspects are processed. So, we know that aspect, but beyond that, I think we're still trying to learn some of the details because of the methodological design challenges of capturing something as loose and complex as love.

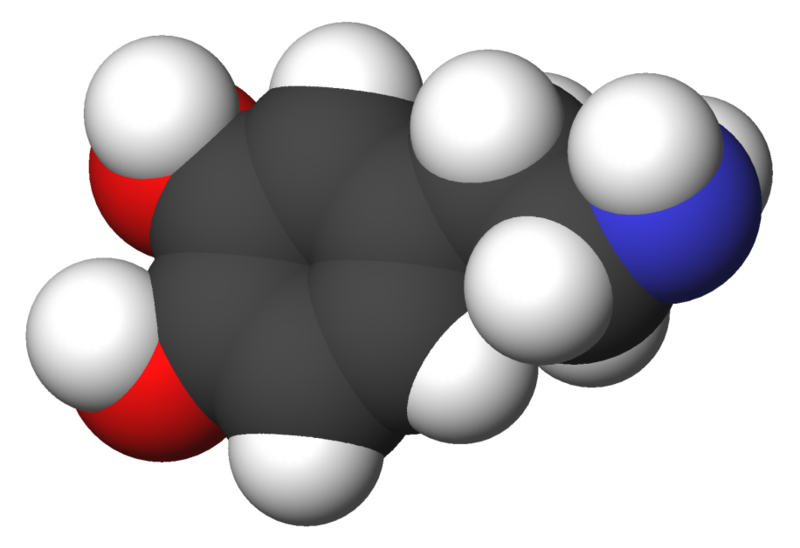

Kat - And we hear a lot in the media, the media loves to talk about this hormone called oxytocin. It's the love molecule, it's the cuddle hormone - really?

Alex - I would say not really, to be honest and so, what's interesting about oxytocin is, we see it across animal kingdom. It's pretty ancient. By the best guesses, I think it's been around for at least 700 million years and so, a lot of the work that started out on oxytocin was first in animals. What they found was when they administered oxytocin to rats for example, to mothers who hadn't died giving birth, they started showing a lot of maternal tendencies and when they restricted oxytocin, even the rats that had given birth started to act a lot more cruelly to their children. So that was a big indicator of maybe maternal love. And then with prairie voles for example, they found that, "Hey, they have much more of this distribution of the oxytocin receptor network which seems to be regulating the monogamy whereas with other species of voles, you don't see the same distribution and you don't see monogamy." So then we move on to the human work and there's been evidence that it's related to things like trust, and empathy and love, but in the last couple of years, we're starting to discover the dark side of oxytocin. Now, we're seeing things like, it promotes more jealousy and greed, and potentially envy, and gloating and so on, and so forth. So, I think it's a very complex molecule that does a lot and we're really starting to just learn about it.

Kat - I want to bring in Gert here as well because love isn't just about these kind of feelings of closeness and trust or even this kind of evil, dark feelings. Love is very pleasurable and not just sexually pleasurable. Being in love is nice. We know from other studies that chemicals like dopamine are involved in these things of pleasure. Does the same apply to love?

Gert - I would say, it does, but we only have indirect evidence for a role of dopamine in love. When we studied the MRI scans that are made, we do see activation of region that contain a lot of dopamine, but that's only indirect evidence. What you actually would like to do is study the role of dopamine for example in PET scanners and as far as I know, that haven't been done.

Kat - It's not very romantic, being in a PET scanner though.

Gert - No, it's not and also, being in an MRI scanner is not very romantic. It's a lot of noise.

Kat - Do we know about any other chemicals in the brain that might also be involved in this kind of pleasurable feelings of falling in love?

Gert - No, I think there's some idea about the role for serotonin for example. We know that serotonin is critical for mood and when you're in a happy mood when you're in love, I would say serotonin particularly must be involved, but also, that is indirect evidence because as far as I know, not many studies have been done on the neurochemistry of love, not in humans anyway.

Comments

Add a comment