Molecules that Mediate Monogamy

Interview with

Chris - What's going on biologically to make us monogamous? Professor Larry Young is from the Yerkes National Primate Research Centre at Emory University in the States. He's looking at molecules that mediate this monogamy.

Larry - My research is really trying to understand the social brain, what makes us want to engage in social interactions and form social relationships. The way that I've been going about doing that is by studying these interesting little rodents called prairie voles. Prairie voles look somewhat like a hamster. They're from the Midwestern United States and what makes them so interesting is that, like people they are monogamous. They form bonds like partners which may sound not so strange. In fact, in the animal world only about 5% of species form any kind of relationship with their partner. We do experiments to try to understand what is the chemistry or the genetics that is underlying their ability to form these lifelong bonds with the partners.

Larry - My research is really trying to understand the social brain, what makes us want to engage in social interactions and form social relationships. The way that I've been going about doing that is by studying these interesting little rodents called prairie voles. Prairie voles look somewhat like a hamster. They're from the Midwestern United States and what makes them so interesting is that, like people they are monogamous. They form bonds like partners which may sound not so strange. In fact, in the animal world only about 5% of species form any kind of relationship with their partner. We do experiments to try to understand what is the chemistry or the genetics that is underlying their ability to form these lifelong bonds with the partners.

Chris - What do you think the advantage to something like the prairie voles you're studying is to forming a monogamous bond? The fact that nature does is so rarely, as you point out, suggests that it could be disadvantageous under certain circumstances.

Larry - I think under most circumstances it probably is, at least for most males, disadvantageous for them to form the bonds. If you're a male in most cases you would think that your best strategy would be to mate with as many females as you possibly can. There may be certain types of environments like where the prairie vole goes where there are certain predators around. If you're a male and you mate with females but don't help them take care of the offspring then the female has to leave the babies in the nest every day while she forages maybe all her babies are getting eaten.

Chris - When you study the brains of the animals, presumably this is a behavioural thing, choosing to be monogamous. What do you find?

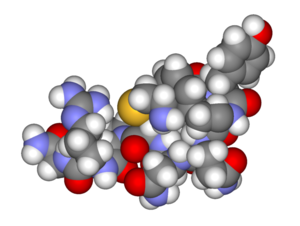

Larry - In the prairie moles there's a molecule called oxytocin. This is a protein hormone that most of us know about because of its role in initiating labour, childbirth and also lactation. This same molecule is known to be responsible for causing mothers to bond with their babies. It's also involved in the female bonding with the male. We know this because we can take a female prairie vole and place her in the cage with a male and don't let them mate. They're not mating partners but if we infuse a bit of oxytocin into her brain she will instantly bond with that male. We can also do a converse experiment where we block the oxytocin and let her mate with a male and she'll never bond with that male. In males it's a different molecule called vasopressin. It's also a protein hormone. It's really interesting that you can have a single molecule like this that plays such an important role in the ability to bond.

Larry - In the prairie moles there's a molecule called oxytocin. This is a protein hormone that most of us know about because of its role in initiating labour, childbirth and also lactation. This same molecule is known to be responsible for causing mothers to bond with their babies. It's also involved in the female bonding with the male. We know this because we can take a female prairie vole and place her in the cage with a male and don't let them mate. They're not mating partners but if we infuse a bit of oxytocin into her brain she will instantly bond with that male. We can also do a converse experiment where we block the oxytocin and let her mate with a male and she'll never bond with that male. In males it's a different molecule called vasopressin. It's also a protein hormone. It's really interesting that you can have a single molecule like this that plays such an important role in the ability to bond.

Chris - Some people have suggested that the bonding process is the same thing between two adult humans and as you get between a mother and a baby. It's just that the love idea, two people getting together, is exploiting the same neurochemistry as when a mother bonds with her baby.

Larry - That's a good point. In all mammal species you have this circuitry in the brain that allows the mother to bond with the baby and take care of the baby. That's an essential kind of behaviour. Oxytocin's released when she gives birth and when she is nursing her babies. Oxytocin is also released when animals mate. It seems that what happens on the occasion when evolution prefers the monogamy kind of behaviour that those circuitries get tweaked a little bit. Now the bond is not towards the baby but, in addition, towards the male partner.

Chris - So having sex does drive a stronger bond, establish trust between a male and a female? That could be part of the role of this hormone system - to make people who are going to have offspring bond together so they'll take care of that offspring.

Larry - We believe that to be true. We know oxytocin is involved in that and it's interesting that you used the word trust. There have been some studies in humans now to ask, does this hormone really affect human behaviour and human mating? The studies are pretty convincing that it does. There was one study that showed if you inhale oxytocin you trust other people more. You can actually infer their emotions better by just looking at their facial expression. It seems that oxytocin is tugging us in to a social world around us.

Chris - You mentioned that in females it's the oxytocin playing a big role and in males there's a different molecule, argentine vasopressin. Why is there that dichotomy? Do the two hormones have the same effect in the opposite effect, they're just used differently?

Larry - Argenine vasopressin is a sexually dimorphic molecule which means that males have much more of this than females. If you look across the animal kingdom you'll find that vasopressin tends to do the behaviours that are, sort of, the macho behaviours of that species. In some species it increases aggression. It increases territorial behaviours and whatever the males of that species typically do, that's what vasopressin controls. It seems in monogamy involved in this species it was tweaked a little bit so that the same hormone that controls macho behaviour now controls this bonding behaviour.

Larry - Argenine vasopressin is a sexually dimorphic molecule which means that males have much more of this than females. If you look across the animal kingdom you'll find that vasopressin tends to do the behaviours that are, sort of, the macho behaviours of that species. In some species it increases aggression. It increases territorial behaviours and whatever the males of that species typically do, that's what vasopressin controls. It seems in monogamy involved in this species it was tweaked a little bit so that the same hormone that controls macho behaviour now controls this bonding behaviour.

Chris - If we look at people that do seem to have a problem with a roving eye, they can't keep their hands off anyone of the opposite sex, do they have a problem with that hormone system?

Larry - We don't know that for sure. We're just at the very beginning of doing human studies. There has been an interesting study that came out that does suggest the vasopressin receptor, which is the protein that responds to vasopressin much like a key in a lock system, and there are variations in that gene. We found in voles that if you have a certain variation of that receptor you were much less likely to form an attachment with a female than if you had other variations. A Swedish group has done a similar study in humans and found that individuals who have two copies of one particular variant of the vasopressin receptor gene are twice as likely to report that they have crises in their relationship of the past year or twice as likely to never get married in the first place. They remain in a live-in relationship but no commit to marriage. It seems possible this system may have some impact on our own ability to form relationships and the kind of relationships that we form.

- Previous The Genetic Root of All Teeth

- Next Advertising Fertility

Comments

Add a comment