Biological Link between Cancer and Depression

Interview with

Chris Smith: Now also in the news this week, researchers at the University of Chicago have identified a potential biological mechanism that can link cancer with depression, and we are joined by Dr Leah Pyter to tell us a bit about it. Hello Leah?

Leah Pyter: Hello!

Chris Smith - Welcome to The Naked Scientists! So do tell us, what is the evidence then that people who get cancer get depression, because obviously that's a pretty traumatic diagnosis to receive. Are you saying then that people get depressed before they get their diagnosis of having cancer?

Leah Pyter: Well basically what we know is that patients with cancer have a higher likelihood of also developing depression at some point in their disease progression, so whether that occurred before and is predisposing them to cancer, or it's due to the tumours themselves, or other aspects of having the disease, we don't know. We were only studying right now whether the cancer itself can cause depression.

Leah Pyter: Well basically what we know is that patients with cancer have a higher likelihood of also developing depression at some point in their disease progression, so whether that occurred before and is predisposing them to cancer, or it's due to the tumours themselves, or other aspects of having the disease, we don't know. We were only studying right now whether the cancer itself can cause depression.

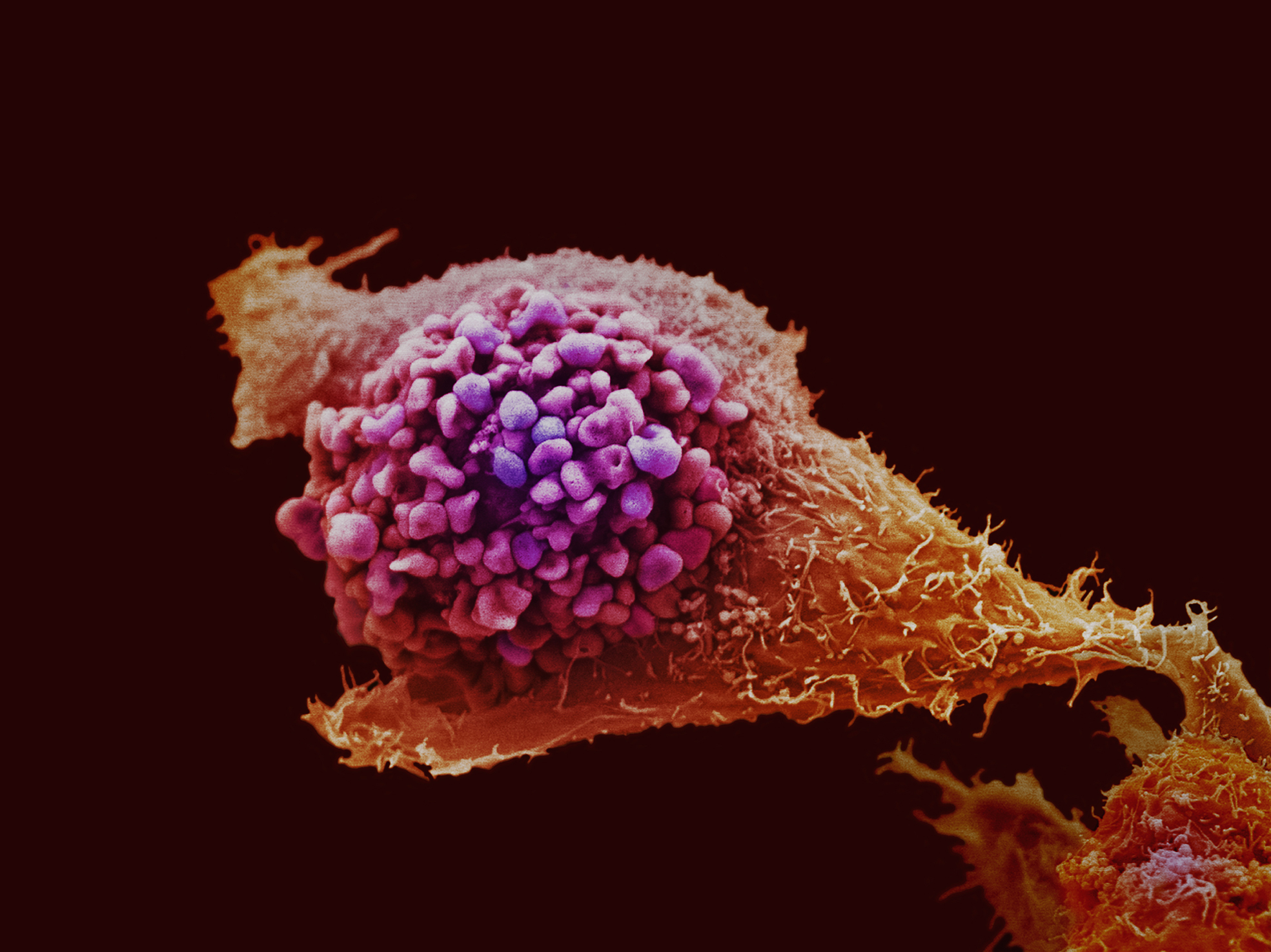

Chris Smith: How could a tumour trigger depression, because a tumour can occur anywhere in the body, therefore at the remote sites in the brain, so how could it trigger changes in brain activity?

Leah Pyter: Sure, well what we hypothesized was that the tumours themselves can produce cytokines which has been shown before.

Chris Smith: These are inflammatory chemicals that drive the immune system?

Leah Pyter: Right, exactly! And there is also a pile of research on how cytokines can access the brain specifically regions of the brain that are associated with depression and anxiety and emotional behaviours, and they can access the brain both tumourally through the blood, or neurally through the vegas nerves.

Chris Smith: So what did you actually do to get to the bottom of how cancer might be able do that?

Leah Pyter: First of all, we are using an animal species, rats, in order to isolate just the physiological impact of having a tumour from the psychological impact of having the disease. We induce tumours in rats and had controls, and then looked their depressive and anxiety-like behaviour along with some physiological measures of these cytokines and the stress access.

Chris Smith: So you'd give rats the cancer. Can you show that when they get the cancer they do develop a sort of depressive or anxious-like syndrome consistent with having - or contemporaneously with having the tumour?

Leah Pyter: Exactly, yes! That's what we did - basically we used standard behavioural tests in these rats that have been used to develop pharmaceuticals, like antidepressants and you have control animals and we measured these types of behaviours and made sure that they only developed following the presence of a tumour.

Chris Smith: And once you'd confirmed that the rats do seem to get depressed when they get a cancer, how did you then find out what was going on to make them feel like that?

Leah Pyter: Well, we had two candidates, one were the cytokines that we have some information about associating with depression, and the other was via the hormone access that regulates stress responses; and so we were able to measure cytokines in the tumours themselves, in the blood as well as the brain in animals with and without tumours, and we also measured one of the stress hormones in response to a stressor and found that cytokines were increased in the brain if you had a tumour and your hormone response to a stressor was dampened if you had a tumour, relative to controls.

Chris Smith: So the cancer is definitely inducing biochemical changes in the brain that might trigger depressive symptoms. We can treat depression though. Why is it important to have identified this problem, and how can it help us to make people who have cancer have a better outcome?

Leah Pyter: Right. So I think one of the things we were keying in on is that a lot of chemotherapies are cytokine-based and so if you're having a patient that is displaying depression along with the cancer you might try to switch the chemotherapies but it's also important because cancer patients that are depressed are less likely to stick to their medical programme and are more likely to succumb to the disease. So not only treating the cancer but also the depression is important for their wellbeing.

Leah Pyter: Right. So I think one of the things we were keying in on is that a lot of chemotherapies are cytokine-based and so if you're having a patient that is displaying depression along with the cancer you might try to switch the chemotherapies but it's also important because cancer patients that are depressed are less likely to stick to their medical programme and are more likely to succumb to the disease. So not only treating the cancer but also the depression is important for their wellbeing.

Chris Smith: Thank you very much. Leah, thank you for joining us! That was Dr Leah Pyter who is at the University of Chicago, she and her colleagues have published a paper in this week's edition of the Journal, PNAS, in which they explained how things like cancers can change the behaviour and particularly to cause behaviours like depression, which as she just explained, can have a major impact on how well someone does in terms of their therapy and their long term prognosis

Comments

Add a comment