The Man Who Ate His Own Experiments

Interview with

Chris - Now from the depths of deep space to the depths of your stomach, and if you've ever been afflicted by an ulcer or gastritis, here's the man who won a Nobel Prize for discovering the bacterium - Helicobacter pylori - that is responsible.

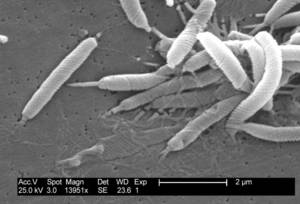

Barry - I'm Barry Marshall. Here I am at the Q.E. II Medical Centre in Perth. It began in about 1981. At that time, I suppose I was 30 years old, and I met up with Dr. Warren who had seen these curved bacteria on stomach biopsies - he's a pathologist you see. And so there was a curiosity for us to investigate this further: How come bacteria can live in the stomach which is supposedly full of acid and kills bacteria? So nowadays, we know that bacteria can live in hot springs, but that was pretty much new stuff in 1981. And so we set out to perhaps identify and culture these bacteria and I went off to interview all the patients that had them on the biopsy to see what was wrong with these people.

Barry - I'm Barry Marshall. Here I am at the Q.E. II Medical Centre in Perth. It began in about 1981. At that time, I suppose I was 30 years old, and I met up with Dr. Warren who had seen these curved bacteria on stomach biopsies - he's a pathologist you see. And so there was a curiosity for us to investigate this further: How come bacteria can live in the stomach which is supposedly full of acid and kills bacteria? So nowadays, we know that bacteria can live in hot springs, but that was pretty much new stuff in 1981. And so we set out to perhaps identify and culture these bacteria and I went off to interview all the patients that had them on the biopsy to see what was wrong with these people.

Chris - What made you think there might be something in the clinical history that'd be worth investigating? Why did you decide to follow that up? Because it would've been easy to just say - oh there are some bacteria in the stomach - maybe we missed them before.

Barry - Well, they were new so obviously there was no knowledge about them, so we had to exclude the possibility that they were causing a disease. And when we did interviews with people we found that there were one or two symptoms that seemed to be connected in some way. Dr. Warren knew already that they caused inflammation in the stomach - which was gastritis - but the teaching was that everybody got gastritis if they lived long enough and who knew what was caused by spicy food, or smoking, or alcohol, or some of the hundred different explanations?

But according to his pathology results you really had to have the bacteria to have gastritis. So we then set out to find - what about people who don't have the bacteria - do they have white cells in the lining of their stomachs? Do they have any symptoms? And we went off with open minds just trying to find out what the patients would tell us, and we came back with nothing initially because people could have indigestion, or belching, or dyspepsia, or nothing, or anaemia, all kinds of weird things, or ulcers, but nothing came out in our pilot study.

So we said - okay let's do it properly now - we'll do a prospective study. We'll look at 100 patients, we'll take every single patient having an endoscopy down - so a very big mixture of people. It was done blinded, so you didn't know what was wrong with them or what the results were, and when we looked at the results, the ones with ulcers had the bacteria far more commonly than just anybody else. So that was a significant result, and that was a year later that we had that result and we had already studied the literature, and it all fitted together all of a sudden. Hang on a minute - maybe ulcers are not caused by stress. Maybe they're caused by a germ in the stomach! Nobody had ever thought of that, because supposedly you couldn't actually have bacteria in the stomach because the acid kills them. So once you say - well that was wrong - all of a sudden it's wide open.

Chris - The question is though - it's one thing to say there are bacteria in the stomach and there's an ulcer, but how do you resolve the question - the bacteria are there because they've caused the ulcer, rather than the ulcer has made the stomach environment change in such a way that it now allows these bacteria to persist?

Barry - I'm getting déjà vu because that's exactly what people used to say who didn't believe us. And so we said - we have to prove that these bacteria are harmful or harmless. And of course, that is an experiment called Cox's postulates, where you have to infect an experimental animal with the bacteria. But sadly, we didn't have a successful experimental animal, so we had to then look for human volunteers. And Warren and I discussed this and he couldn't be a volunteer because he'd already had Helicobacter and I had treated him, so he would've been a bad choice, and I hadn't had them.

So it fell upon me to do the experiment. So I did drink the bacteria - a few tablespoonfuls - not very much, and it didn't really - well actually, it's not published yet, so I won't tell you what it tasted like! It wasn't too bad. So then I was just waiting to see what would happen. By then I knew that there were lots of people who didn't have ulcers who had the bacteria, so I was there like - I suppose nothing will happen because none of my ulcer patients can remember catching a bacteria, so probably they're not going to cause any problem. So I was of course surprised when about five days later, I woke up and ran into the bathroom and started throwing up, and I was vomiting for about three days. There were a lot of vague symptoms but nothing that you could really hang your hat on. And then after that I was okay, and the endoscopy was done. And sure enough, I had millions of these bacteria, thousands of white cells all trying to eat the bacteria - so it was really a bacterial infection that I had in the stomach. So that answered this question that said - healthy people with nothing wrong with them could catch this bacteria and then get inflammation in the stomach -called gastritis. So that was then the soil upon which an ulcer would form later in life, and so we connected the whole story up at that point.

Chris - So what is the bug actually doing and why is the immune system not dealing with it?

Barry - Well, it's a bit like D-day. All the ships are parked offshore, out of range, firing at the coast - and so Helicobacter is like that, living in a mucus, hammering away at the epithelial cells, making them a little bit leaky, so that they leak iron and nutrients up to the bacteria, so that's the happy status for the bacteria. As soon as you get too many white cells migrating through the epithelium in the stomach, it's starting to develop holes in it, it becomes leaky, acid goes down, and you develop an ulcer. So that would be disadvantageous for the bacteria. They don't want to kill you because then they can't propagate.

Barry - Well, it's a bit like D-day. All the ships are parked offshore, out of range, firing at the coast - and so Helicobacter is like that, living in a mucus, hammering away at the epithelial cells, making them a little bit leaky, so that they leak iron and nutrients up to the bacteria, so that's the happy status for the bacteria. As soon as you get too many white cells migrating through the epithelium in the stomach, it's starting to develop holes in it, it becomes leaky, acid goes down, and you develop an ulcer. So that would be disadvantageous for the bacteria. They don't want to kill you because then they can't propagate.

So a successful bacteria lives in sort of symbiosis. So what they want to do is keep the inflammation going, but not so vigorously that you'd die from a bleeding ulcer. So an ulcer is actually [when] the bacteria is a bit over zealous, if you like, in harming you, it doesn't want to do that. It has toxins, and one of these toxins called the VacA toxin probably down regulates the immune system. So as soon as you get too many holes in the mucosa, this stuff would be leaking into the lining of the stomach and inhibiting the proliferation of the white cells. So that's the kind of thing that it would be doing. So your immune system then is a bit paralysed and doesn't actually become more vigorous as it would do. So, you can imagine maybe 500,000 years ago, the first Helicobacter infects humans - it is too dangerous and the poor old humans probably die from bleeding ulcers. However, one of the Helicobacter mutated and developed this immune suppression system and got the right balance, and now we all have Helicobacter all our lives, or we used to, but in the last 100 years it has decreased to about 25% of population in most countries.

So you can pick it up as a child and it sits there, controlling the immune system, regulating it for the rest of your life. And so it's a very mild irritation in the stomach, and most people don't know that they have it. 10% of people at some time in their life develop ulcers and that is a major event because ulcers then come and go. So it would put you in the high list acid level and then if you have Helicobacter all your life, that irritation and inflammation attracts stem cells floating past and these stem cells try to fix up the problem in the stomach, trying to make it heal, and they're proliferating and they are subject to hits by carcinogens that you might eat, so you do get 1 or 2% chance of having stomach cancer if you live as long as a Japanese person - you know, 80s or 90s.

Chris - Barry Marshall - the man who ate his own experiments to prove that the bacterium Helicobacter pylori can cause stomach inflammation, ulcers, and even cancer. And Barry also told me that he's now working on a way to produce tamed forms of that bug, that can be used to deliver vaccines against other diseases like the flu.

Comments

Add a comment