The Importance of Monster Hunters

Interview with

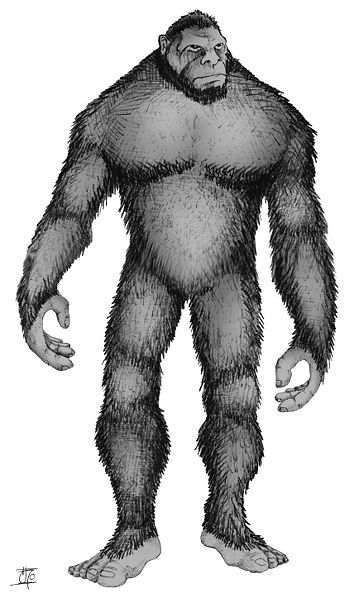

Kat - Brian Regal is Professor of the History of Science, Technology and Medicine at Kean University in New Jersey, USA. He's investigating the phenomenon of monster hunting, the search for creatures such as Big Foot. I started by asking him what first got him interested in these strange creatures and the strange people that study them

Kat - Brian Regal is Professor of the History of Science, Technology and Medicine at Kean University in New Jersey, USA. He's investigating the phenomenon of monster hunting, the search for creatures such as Big Foot. I started by asking him what first got him interested in these strange creatures and the strange people that study them

Brian - I guess I was always interested in the more unusual aspects of history. As a doctoral student I was working alone on the history of evolution theory. That's what I've mostly published on. As I was doing that I was finding often the corners of the history of evolution, these unusual stories about people and unusual ideas. I came across monster hunting. As I like the stranger aspects of history I was immediately attracted to it. The more I looked into it the more I saw as a historian there was materials available in libraries and archives around the world that could allow me to do serious scholarly research into this field that had been essentially passed over by traditional historians of science and had become like monsters themselves; the domain of passionate amateurs. I saw immediately the similarities between the history of monster hunting and the history of amateur natural history study in general.

Kat - What sort of monsters are we talking about? Can you give us some names we might be familiar with?

Brian - I use the term monster as a generic term. Mostly what I work on what I call anomalous primates. Human and primate-like animals that show up in places that conventional wisdom says they shouldn't show up: the yeti, sasquatch, bigfoot, orang pendek: there's about 100 different names for animals around the world that are sort of monkey-like, kind of human-like. They have traditions of being mythical animals, of scaring the local populous and kind of existing in places where science normally says they shouldn't.

Kat - If science has been looking at this and says they shouldn't be here what sort of tack are amateur scientists taking?

Brian - The thing that's interesting about the amateurs is that they tend to ignore what the mainstream scientists tell them. The mainstream scientists generally, not all. There are some mainstream scientists now and in the past who thought these animals were real. Generally speaking most biologists and zoologists say that from an evolutionary point of view these animals don't make any sense. The amateurs as being amateurs, not having that kind of formal training, just say, "Well we don't care what you say about this theoretically. We have the evidence. We've seen these animals, we've seen their footprints. We've taken pictures of them, we've interviewed hundreds of eye witnesses and we're going to base our opinion on the fact of this evidence that we have and ignore what theory says: shouldn't be there."

Kat - So we have theory on one side saying no. We have evidence on the other side saying yes, things liek bigfoot do exist. What do you reckon? Where do you think the balance lies?

Brian - Well, you see I have an easy out for all of this. I'm not a zoologist, I'm not a biologist, I'm not a scientist of any kind. I'm a historian. I can step back with a historian's eye and watch both sides and I have no interest really in proving one way or the other. My research is not geared towards saying yes they exist or no, they don't. I will let better, more qualified people make that decision. In fact, if it doesn't exist it's to my benefit because then I get to ask question like well, if this thing doesn't exist why do so many people believe that it does? If it does exist that sort of takes a bit of the interest out because no one is amazed that people believe in bears. No one gets amazed when someone says I just saw a hawk fly by. If someone says I was just looking out my back window and bigfoot walked by then all of a sudden people are interested.

Kat - As a scientist one of the things you dread hearing is, "I'm no scientist but..." What does your kind of research tell us about maybe the role of amateur scientists? Can we ever find agreement? How can scientists and amateur scientists work together?

Brian - The role in amateur science is extremely important in the history of science in general, especially in the West. It goes all the way back to the late 1400s here in England when the first amateur naturalists appear. What you see happening is that if you look at the history of natural history and the role of amateurs in it you see that a pattern emerges. Whenever some knowledge domain which has the potential to generate genuine scientific knowledge appears what will happen is slowly but surely members of the amateur community will become more professional. Outside professionals will become more interested. A kind of displacement occurs where as more and more genuine information is generated and mainstream science, for lack of a better term, becomes more interested in this topic more professionals will get involved and they will push out or displace the amateurs until you reach a point where the amateurs have been pushed out completely. It becomes a professional scientific discipline. We've seen this over and over again with fossil hunting, with ornithology and bird watching, with plant collecting, botany, marine biology. Whenever some field is begun by passionate amateurs and it has the potential to generate genuine scientific information it will eventually professionalise and the amateurs get kicked out.

Kat - Are there any field where you see this happening now? For example, the search for big animals or maybe UFO studies?

Brian - I suppose they have the potential but they haven't quite reached that point of critical mass yet. Because with all due respect to the amateurs who believe otherwise there really hasn't been any evidence of flying saucers or ghostly spirits or bigfoot produced that makes most of the scientists in the mainstream sit up and take notice. That is sort of a two-edged sword of these kind of fields because the amateurs want very much to get scientists and the mainstream interested but in the back of their minds they known that the moment the mainstream does get interested that marks the beginning of the end of their involvement. The day somebody comes in to a major university and throws a sasquatch carcass on the dissecting table it's all over. It's no longer fringe science. It's no longer pseudo science or any of the other words that are sometimes used to describe this. It's now anthropology. The amateurs, the crackpots are out and the eggheads, the professionals take over. That's the end of the story.

- Previous Superheroes of Science

- Next The Power of Imagination

Comments

Add a comment