Thinking of pain

Interview with

When we feel someone else's pain, are we using the same parts of our our  brains that enable us to experience our own pain, or does it work differently? Anjali Krishnan, at the City University of New York, has come up with a clever way to dissect apart the two, as she told to Chris Smith...

brains that enable us to experience our own pain, or does it work differently? Anjali Krishnan, at the City University of New York, has come up with a clever way to dissect apart the two, as she told to Chris Smith...

Anjali - Imagine that you've just jammed your finger in the car door and you know you feel pain because your finger is hurting and you're bleeding. What we discovered in our work is that explains you've just had a feeling physical pain yourself does not share the same brain processes that will happen to you when you watch your best friend jam her finger in a car door. But you know that both of you have to feel pain. So the question we wanted to ask is, when you know that there seems to be some kind of overlap in the experience, when is there really an overlap in the brain and if there is, where is this overlap located?

Chris - Because for a long time, we've had this concept of mirror neurons, haven't we, and people have said, when I watch someone stub their toe, hit their thumb with a hammer, or do something, the "ooh!" that I voluntarily want to say is basically me, mapping onto the same circuits in my brains if I were feeling the pain they experience. But you're saying, actually, it's more subtle than that.

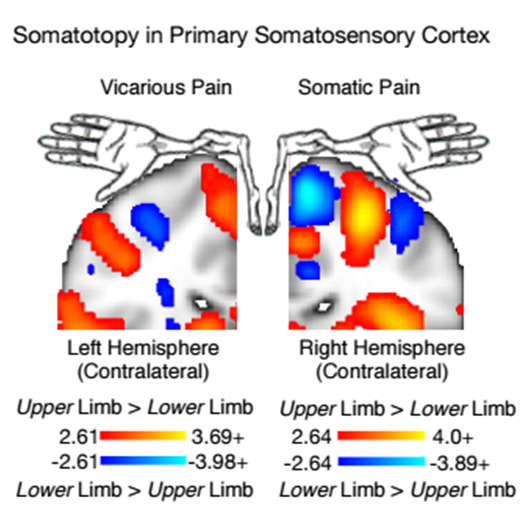

Anjali - Yes, because what we found is that regions when you stub your toe or you jam your finger involves some of the somatosensory regions in your brain. These are the regions that get information from the receptors at the site of injury and then tell your brain, "Wait! There's something abnormal that's happened and it's painful." But when somebody else has the same experience and you are just an observer, what you're actually doing is you are mentalising, thinking about that person's experience and cognitively deciding that that person is undergoing pain, rather than physically feeling your fingers getting hurt in some way or the other.

Chris - How did you manage to dissect apart the vicarious experience of your best friend slamming her finger in the door versus what happens when you do it yourself? How did you actually manage to unpick that it's separate?

Anjali - In the study, we had volunteers take part in two different sessions of an MRI experiment. Their brains were scanned when they performed two different tasks. The first task, they were given thermal pain at three different temperatures. In the second task, they were asked to view pictures of people receiving some kind of injury at three different levels - foot getting stubbed, or a hammer falling on a finger, there were some really gory ones where it looked like a chainsaw was going to cut off a finger. So, their task in the scanner was to either receive the thermal pain or view these pictures and then at the end of each trial, they rated on a scale how much sensation they felt. Now, it's very important the instructions that they were given. In the thermal pain, it was fairly obvious they felt the pain and they had to report how much pain they felt. But in the vicarious pain session, they were asked to imagine that the situation in the picture was happening to themselves and to rate how much pain or how much sensation they would have felt.

Chris - Right. So we're comparing the relative activity in the brains of these individuals as they either experience pain for real themselves or they're asked to imagine how much pain another individual would be feeling. And so, you can see whether it's the same or different brain areas which are activated under those settings.

Anjali - That is the general idea of the analysis.

Chris - When you do this, what do you find? What do you see?

Anjali - Perceiving somebody else in pain does not use the same regions in the brain as when you experience pain yourself. Instead, we use regions in the brain that are involved in understanding another person's mental state, their intentions, their preferences. So, it's something more cognitive than sensory.

Chris - So, the previous idea that there was sort of a mirror circuit where you do actually superimpose someone else's pain on your own pain circuits, that's actually a myth then. You're saying that's not right.

Anjali - Well, I think what we've done is we've improved upon some of those ideas and we've used more tools that are now available to us. So in our earlier research, people looked at different parts of the brain independently of each other and they compared these different independent regions to come up with regions important for physical pain or vicarious pain. What we've done is we've taken a more whole brain approach to the analysis and what we've found is that we look at the whole brain, the two different experiences recruit different parts of the brain network.

Chris - Is this not just a rather subtle interpretation of how we're doing brain scanning or is there a really important implication from having discovered this difference?

Anjali - It's important because then you have a way to target let's say even treatment. If you know the network that is involved in physical pain, what you might do to alleviate the pain could be different from what you would've done if you know that the network was different for vicarious pain. This is just an example but it's one of the ways where knowing why there's a difference is important.

- Previous Abbie Fearon - Signals in cells

- Next On the move

Comments

Add a comment