Post Traumatic Stress Disorder

Interview with

Ben - Can you trust your memory? It seems that a large proportion of people, when asked, can remember seeing things that they have never had chance to see, such as footage of the London bus bombings that has actually never been shown. While the unreliability of memory is something we should be concerned about in a legal setting, more damaging to our health are the memories that we just cannot forget, such as the debilitating flashbacks occurred by sufferers of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, or PTSD.

'Memories in Distress' was the title of the talk given at the BA Festival of Science by Peter Naish, who normally resides at the Open University. He explained to Meera how, in PTSD, the brain can be fooled into accepting a memory as if it were happening in front of your eyes. Definitely both a distressing memory and your memory in distress...

Peter - The event is covering a whole spectrum of memory problems. These problems seem to be associated with processes that make people very unhappy sometimes, this can be the fact that when people tend to be a bit depressed anyway, they seem only able to remember sad events in their life and all the good times fade into the background. An even worse thing to put up with is Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, when people get terrible flashbacks of some shocking event in which they took part, like a road traffic accident. I'll be telling the story of someone who was trapped on one of the underground trains when the terrorist bombs went off, and afterwards for a long time she got vivid flashbacks, so vivid she felt she was still there on the train. She believed that the flashbacks, which only lasted a short while, were real life, and that she was still in the train and was going to die. Really a horrible experience that went on for months.

Peter - The event is covering a whole spectrum of memory problems. These problems seem to be associated with processes that make people very unhappy sometimes, this can be the fact that when people tend to be a bit depressed anyway, they seem only able to remember sad events in their life and all the good times fade into the background. An even worse thing to put up with is Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, when people get terrible flashbacks of some shocking event in which they took part, like a road traffic accident. I'll be telling the story of someone who was trapped on one of the underground trains when the terrorist bombs went off, and afterwards for a long time she got vivid flashbacks, so vivid she felt she was still there on the train. She believed that the flashbacks, which only lasted a short while, were real life, and that she was still in the train and was going to die. Really a horrible experience that went on for months.

Meera - What happens in someone like that's brain in order for them to actually believe that the 'dreams' they're having are reality?

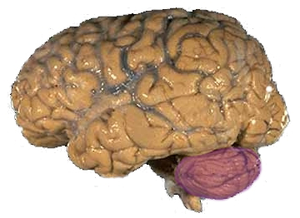

Peter - We have to go back and consider how memory works. The brain really is an information processing system. So all the information that our senses acquire about our world, they have to be analysed so that we can make sense of it. The brain has specialised areas, some that deal with visual processing, some for sound, and even within those there are sub-divisions to do different tasks. Finally, you as it were put it all together and you have your impression of what is going on around you. As the information goes through the brain, it leaves a trace, and that trace is a memory. Now because it's all distributed, you have to have a process that can assemble things. This seems to revolve around a part of the brain called the hippocampus. It's the part of the brain that gets bigger in London taxi drivers when they learn the entire A to Z, so wherever you ask them to take you, they know it - just like that! It's a prodigious memory feat, and their brain actually gets bigger as a result. So the hippocampus gathers together all the relevant little pieces of information for the particular memory you're trying to resurrect.

But there seems to be another system which one imagines must be the more primitive one. When memory got underway for animals, it must have been a thing for safety. If you have a scary experience, and your brain is designed to recognise that it's dangerous, so you run, the next good thing to do is to remember that - so if some of those scary things start to show up, it triggers exactly the same response. In other words, you feel frightened even if you haven't seen anything dangerous yet. That is looked after by another part of the brain, not the hippocampus, a region called the amygdala. It would seem that when people get Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, PTSD, it look as if the Amygdala has taken over. So it's almost like having a library, all the books are our little details and we assemble the little books to get the complete story - that can be done with a good, well ordered librarian, the hippocampus. Or there's this maniac who just keeps dashing in and getting the books and shoving them under your nose, you've got to read them. That is PTSD.

Meera - So you're saying that when someone is taken back to distressing times, the amygdale is pushing out the happier memories from the hippocampus and placing the worse memories in, and that's what they're experiencing?

Peter - I think the amygdale is principally involved, the story I was just telling, is particularly for post traumatic stress disorder, which is far worse than simply being depressed, although that's bad enough. The amygdale seems to be involved when the memory simply will not go away, the slightest thing can trigger it. The lady I mentioned who suffered in the tube bombings, she dreads firework night. She hears an explosion and there's nothing she can do about it, the memory's there in front of her eyes as if she's back on that train. Whereas other things will jog your memory, someone says something or you perhaps have a smell that you remember and you think 'Oh, that takes me all the way back to... whatever', but you don't then have to keep thinking about it. It takes you back, it doesn't make you think you're there. But the amygdale seems very much to collect all of the raw sensory information coming in, before it's well processed. It makes something that looks just like it would if information really were coming in. The poor brain, a bit further downstream, doesn't know the difference. It gets information that seems to be coming from the senses, and it treats it as real.

Meera - So now that you know what's happening in the brain, what is the research being done in order to help people that are having, say, recurring nightmares or Post Traumatic Stress?

Peter - We are getting better, we have someone speaking here today, Professor Anka Aylas, together with her colleagues, her husband professor Clarke. They have developed a very nice programme for PTSD, which gently has to take people back in their mind to these, they call them 'Hot Spots', the key things that just keep coming back into their minds. And little by little, the 'sting' is taken out of it, as it were, and it lets the information be processed really in the proper way. It looks as if it's letting the hippocampus do its normal job, and that takes over and turns it into a more well behaved memory which will sit on the library shelf until anyone wants it. Of course, these poor people aren't going to want it in a hurry!

Ben - A promising, and surprisingly simple way to tackle Post Traumatic Stress disorder, and let people who have been through disaster return to a normal life. Peter Naish there, talking to Meera Senthilingam at the BA festival of science in Liverpool.

Comments

Add a comment