Language in the Deaf Brain

Interview with

Chris - This week, we're talking all about the science of hearing and sound, but hearing isn't just down to your ears. The brain plays a crucial role so now, we're joined by Dr. Mairead McSweeney who's from the Institute of Cognitive Science at University College London. That's where she works on looking at how a deaf person's brain deals with language. Whether that's sign language or lip reading or reading from text, and she's with us now. Hello, Mairead.

Mairead - Hello.

Chris - Tell us a little bit about the deaf persons' brain. How does it differ or not from someone who is normally hearing?

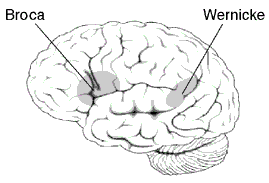

Mairead - Well to date, only a few studies have actually been done to look at the structure of deaf people's brains and perhaps surprisingly, these studies suggest very few, if any, anatomical differences between deaf and hearing brains. So for example, we might wonder what happens to the part of the brain that processes sound in you and I, the auditory cortex, and might predict that this may be atrophied in people who were born deaf. But that doesn't seem to be the case. So, in people born deaf, their size of auditory cortex seems to be the same as in hearing people. What it's actually doing is a different question I can perhaps tell you more about that if you're interested later. And when we think about function and how the brain processes language, very similar neural systems seem to be recruited by deaf and hearing people. So in hearing people processing spoken language and deaf people processing - in our case British Sign Language, which is a real language and is fully independent of spoken English - then the same neural systems seem to be recruited. And these are predominantly located in the left hemisphere of the brain.

Mairead - Well to date, only a few studies have actually been done to look at the structure of deaf people's brains and perhaps surprisingly, these studies suggest very few, if any, anatomical differences between deaf and hearing brains. So for example, we might wonder what happens to the part of the brain that processes sound in you and I, the auditory cortex, and might predict that this may be atrophied in people who were born deaf. But that doesn't seem to be the case. So, in people born deaf, their size of auditory cortex seems to be the same as in hearing people. What it's actually doing is a different question I can perhaps tell you more about that if you're interested later. And when we think about function and how the brain processes language, very similar neural systems seem to be recruited by deaf and hearing people. So in hearing people processing spoken language and deaf people processing - in our case British Sign Language, which is a real language and is fully independent of spoken English - then the same neural systems seem to be recruited. And these are predominantly located in the left hemisphere of the brain.

Chris - So the same bits of a brain that would be decoding language if you were listening to it are being used to decode language arising through other means of communication?

Mairead - That's exactly right, yes. So, we are comparing languages coming in in very different modalities, so we've got auditory verbal speech, and then we've got visio-spacial sign language, and the same systems seem to be recruited. And of course, if we think about it, we as hearing people also deal with visual language, so you mentioned lip reading, we see people's faces when we speak or we might be reading text, but these are all based on spoken language and we have that auditory system that is involved in processing spoken language and these visual derivatives are then built upon that system whereas with sign language of course, we're looking at something that doesn't have any auditory component. So the fact that the same systems are used for spoken language and sign language is very interesting. It tells us that what the brain is doing is saying there's something important about language that's recruiting these regions in the left hemisphere.

Chris - I was just going to say, how does the brain know this is language and I have to present this information to this other bit of the brain whose job it is to decode language and then parcel it out to the other bits of the brain that then do other aspects of linguistic processing, working out what verbs mean, what the nouns mean, what colours mean, and so on.

Mairead - Well, that's the big question that we're working on really! So it's one thing for us to say this system in the left hemisphere, involving the certain parts of the brain that have been identified for a long time - Broca's area and Wernicke's areas being involved in the language processing - are also involved in sign language, but the next step for our research is really, what is it about language and the structure of language that is important for these regions? What is it that is critical and what is it that these regions can do in terms of symbolic processing, or whatever it might be, that is important for language processing. So that's the next step for our research.

Chris - And you're doing this with brain scanning, so you put people with a hearing impairment of presumably different lengths of time - people who've been born deaf versus people who have acquired forms of deafness - who have learned alternative means of communication, and you look at how their brains respond to different stimuli?

Chris - And you're doing this with brain scanning, so you put people with a hearing impairment of presumably different lengths of time - people who've been born deaf versus people who have acquired forms of deafness - who have learned alternative means of communication, and you look at how their brains respond to different stimuli?

Mairead - Yeah. We're using brain scanning as you say. So we use something called functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) where we can get an indirect measure of blood flow which tells us which parts of the brain are being used when we show different people stimuli, whether it may be sign language or visual speech or written text. But actually, we haven't yet compared people who were born deaf with people who become deaf later in life, most of our work is concerned just with people who are born profoundly deaf. But looking at all of these different groups can address very important questions. So looking at people who have become deaf later in life will be something we'll do in the future because it all tells us about our critical question, which is how experience shapes the brain and how plastic the brain is in responding to changes in its environment.

Chris - And if you look at people in whom the opposite side of the brain is the dominant one because the majority of us are right handed, which means the left side of the brain is the dominant hemisphere and that's usually where language is. If you look at people in which that process is reversed, do you also see the sign language and so on being shifted across as well? Is there always this association between the language bits of the brain and the interpretation of things like sign language?

Mairead - Well, that's a good question actually and it's something we have just put in an application to get money to look at! So actually, looking at sign language processing in deaf people in this way, there's maybe 20 studies that have been published in this area. All have focused on people who are right handed, so we want to have consistency across the people that we're looking at. So in fact, there are no studies looking at deaf people who are left handed and looking at the regions that they use in processing language, but that is something that we plan to do in the future.

Chris - Brilliant. Well, good luck with it Mairead and do join us when you do discover how it is that the brain manages to puzzle out these different bits of information, and know that they're all about communication and therefore, to put them into the right brain area.

Mairead - Will do.

Chris - Great to have you on the program. That's Mairead McSweeney who is from UCL, University College London explaining how a deaf person's brain can process sign language in a very similar way to how a hearing person's brain processes spoken language.

Comments

Add a comment