Bisphenol-A and Human Health

Interview with

Chris - Now this week's show is all about the pollutants that get into water and, therefore also into our bodies. And in particular, chemicals that can leach out from the tonnes and tonnes of plastic that we're using every single day. Tamara Galloway is Professor of Ecotoxicology at Exeter University and she's been looking at the effect of just one of these plastic based chemicals...

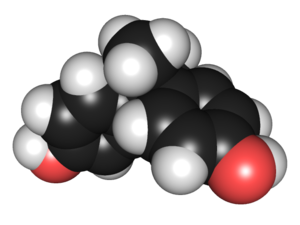

Tamara - We've been interested in a compound called bisphenol-A for some time now because it's highly controversial. It was first produced around about the 1950s and at that time, it was produced as an artificial oestrogen. But it was then found that actually, it was a very useful monomer for making a range of plastics, particularly a kind of plastic called polycarbonate. Now, this is a hugely useful compound because it's makes very clear, rigid plastic which is good for re-usable containers. Previously, it was thought that this compound was extremely safe. However, more recently, results from animal health studies and laboratory studies have suggested that it could be having oestrogenic effects. So that is, it's acting like a hormone in the body.

Chris - Where would we find this stuff, out there in the world or in the environment around us?

Chris - Where would we find this stuff, out there in the world or in the environment around us?

Tamara - Well, polycarbonate plastic is found in a range of rigid containers that are used for things like re-usable drinks bottles. Bisphenol-A is also used to make epoxy resins and these are most commonly encountered as the lining of tin cans. So, these are the two places that probably most humans are exposed to bisphenol-A.

Chris - And the evidence is that this stuff being in the environment and ubiquitous around us, and in these food containers, can get into our bodies?

Helen - Yes. More recent research done in America by the Centre for Disease Control have shown that something like 95 percent of the population has measurable levels of bisphenol-A in their bodies. They worked this out by measuring bisphenol-A in urine samples because what goes in to your body, you have to pass out.

Chris - What do we think this stuff does when it comes out of a food container or whatever, and gets into our bodies? Is it there in meaningful amounts?

Tamara - Well, the evidence has always suggested that it passes through our bodies very quickly. So we rapidly metabolise it and excrete it out in the urine within a matter of hours. So that, combined with earlier studies that suggested it was very safe meant that it wasn't really much of a public health issue. But more recent studies have suggested that, at very low concentrations it could be having an effect as an oestrogen in many animal model studies.

Chris - And why is that bad?

Tamara - That's bad because - oestrogen is a good hormone, it promotes growth and it promotes healthy reproduction - but if it's there at the wrong time and in the wrong place, then it can lead to adverse consequences.

Chris - Such as?

Tamara - Such as, if it's there at the wrong time in development, oestrogen can lead to feminization. So, if there's not enough testosterone and there's more oestrogen, you get feminizing effects.

Chris - And how are you trying to find out, when people are exposed to these things, what those health consequences could be?

Tamara - Well, we were very interested to know, not just what happens in early life, but what happens in the general adult population. We were able to take advantage of a study done in America called the Nutrition and Health Examination Survey and this is a really fantastic program where tens of thousands of American volunteers have had all aspects of their health and nutrition studied. Since the 1980s, this has included the measurement of a whole range of different chemical compounds. And since 2003, it's also included bisphenol-A. Now one of the problems, if you're trying to look for very small effects is that you need very large populations to be able to see them. So this large population offered us the opportunity to search for adverse health effects.

Tamara - Well, we were very interested to know, not just what happens in early life, but what happens in the general adult population. We were able to take advantage of a study done in America called the Nutrition and Health Examination Survey and this is a really fantastic program where tens of thousands of American volunteers have had all aspects of their health and nutrition studied. Since the 1980s, this has included the measurement of a whole range of different chemical compounds. And since 2003, it's also included bisphenol-A. Now one of the problems, if you're trying to look for very small effects is that you need very large populations to be able to see them. So this large population offered us the opportunity to search for adverse health effects.

Chris - So what you're basically doing is - you've got a very big cohort of people, you can then stratify them according to potential exposure or the amount of bisphenol-A that's in them. You can measure that from urine for example...

Tamara - That's right, yes.

Chris - ...and you can then marry that up with medical history. Have they got condition X, Y, or Z, and see if there's any relationship?

Tamara - That's perfectly correct and we had a lot of history on the actual health conditions of the people who were suffering, but also a range of different biochemical measurements and laboratory measurements on the individual proteins and hormones in their bodies.

Chris - And when you do that study, what sort of relationships emerge?

Tamara - Well, quite surprisingly, when we did this study, what we found was that there was a strong association between increased exposure to bisphenol-A, as evidenced by measuring concentrations in the urine, and the presence or the reporting of cardiovascular disease, of diabetes, and of changes in liver enzyme function.

Chris - Is it not possible that people who just eat a lot and therefore being incidentally exposed to large amounts of bisphenol-A, because they're getting a lot of fast food out of food packets and things, that accounts for the fact that they have large amounts of it in their body. And because they put on a bit too much weight, that elevates their stroke, diabetes and cardiovascular risk?

Tamara - Absolutely. Well of course, that was our first thought, but we went back and controlled the data extremely carefully for body mass index, for diet, for socio-economic position, for all of the usual things that might confound this kind of result. And these associations remained robust throughout. So what that meant was that the 25 percent of the population with the highest exposure to bisphenol-A had over a two-fold increase in risk of cardiovascular disease compared to those in the bottom 25 percent. That's quite a big increase in risk.

Chris - It certainly is - obviously this is an association, it's not causal, you don't prove that one thing leads to the other.

Tamara - When you report this kind of association, in scientific terms the most important thing to do next is to show that you can see the same association in a completely separate population. That's called replication and it makes it much less likely that the results that you saw first time were the result of chance. So we went back. The American study had published a second wave of data in September of this year [2009] and we went and examined this study again, to see if we could see the same associations. And we did, so that makes it very unlikely to be a matter of chance.

Chris - This presumably, when people hear this, they find quite alarming, don't they? And they're thinking, "Well how do I avoid getting exposed to these chemicals? Have I been exposed? What can I do to minimize my exposure and is it too late?"

Tamara - Well, there's a second good news part of this story and that's between the first study and the second study, the level of exposure in the general population in America had fallen by 30 percent. We're not entirely sure, we can't say exactly why that is, but it's most probably because of changes in manufacturing processes from companies who are saying; "Well you know, there's all this concern over bisphenol-A. It's not being regulated against at the moment, but let's change our formulation so that the compound is used less." The other good new story is that bisphenol-A does seem to be rapidly metabolised in the body. So if you remove the exposure, it will quite rapidly disappear from the body. So it's not saying, if you've been exposed, then that concentration will always remain within you.

Chris - Which is reassuring. That was Tamara Galloway. She's at the University of Exeter and although they aren't sure yet what the mechanism for these health effects, the heart disease, diabetes, and so on could actually be, they think it could be related to the hormone mimicking effects that we know these chemicals can have. One important point that Tamara also went on to tell me is that they're also very concerned about the amount of plastic that's actually going into, and has gone into, landfill in past because these chemicals could now be leaching out into the water courses, and potentially also groundwater, and therefore, potentially exposing us to trouble in the future.

- Previous Crisis Camps

- Next Oestrogen in the Water

Comments

Add a comment