Supersymmetry and the LHC

Interview with

Ben - Any hypothesis on multiverses will remain just that, a hypothesis, until experimental physicists can find observations to support or refute these ideas. We're joined in the studio now by Dr. Chris Lester. He is a Cambridge University physicist, who also works on the LHC-ATLAS instrument. Thank you ever so much for joining us.

Chris - Thank you.

Ben -

Brian Greene mentioned supersymmetry. So before we go any further, could you just explain what that actually means?

Chris - Supersymmetry is a fairly old theory. It's been around since the '70s or thereabouts. You could think of it as effectively a bit like when you take matter - we all know about matter - and we're aware also that there's antimatter, it's sort of a reversed copy and the charges are all different again, pluses and minuses, and so on in antimatter. If you could flip all of those things again, and imagine creating another mirror image of the world's particles, but instead of changing the charges, if you change the spins of particles so that the particles that had to be spinning originally aren't and the particles that aren't spinning now, have to be. Then those are your supersymmetric particles and there are various reasons for wanting those, including some of the particles that you get out of that could perhaps make dark matter and things like that, that the astronomers are telling us that we need.

Chris - Supersymmetry is a fairly old theory. It's been around since the '70s or thereabouts. You could think of it as effectively a bit like when you take matter - we all know about matter - and we're aware also that there's antimatter, it's sort of a reversed copy and the charges are all different again, pluses and minuses, and so on in antimatter. If you could flip all of those things again, and imagine creating another mirror image of the world's particles, but instead of changing the charges, if you change the spins of particles so that the particles that had to be spinning originally aren't and the particles that aren't spinning now, have to be. Then those are your supersymmetric particles and there are various reasons for wanting those, including some of the particles that you get out of that could perhaps make dark matter and things like that, that the astronomers are telling us that we need.

Ben - Antimatter originally arose as what looked like an error in the maths. Are we getting something similar with supersymmetry? Is this something that sort of has to be there to make things balance or is this something that is key to the predictions of the theories?

Chris - At the moment, we don't have to accept supersymmetry at all. It may simply not be there. But many of the reasons that people are - or those people who are hoping that it's there - one of the reasons that they want it to be there is certainly because it fixes up a number of problems in the maths they don't like. That sort of thing has been useful in the past and antimatter turned out to be true, whether that's going to be the case for supersymmetry, we don't yet know.

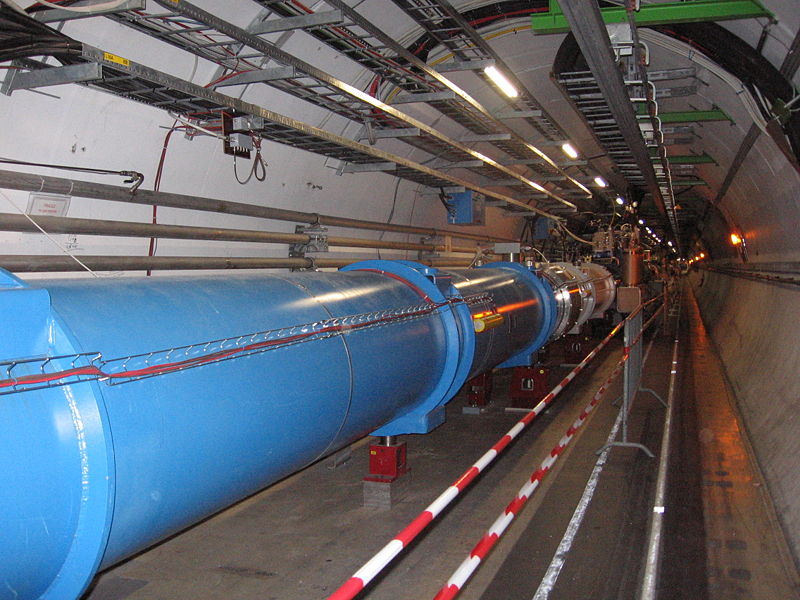

Ben - So, where are we now at the LHC experiments? It obviously had its first run and it's currently cooling down. They'll be switching it on again fairly soon, I think.

Chris - In fact, it turned on again about a week ago.

Ben - Right! I apologise for being late in that case. Sorry, LHC! So it's now back on for its second batch, but what have we got from it so far?

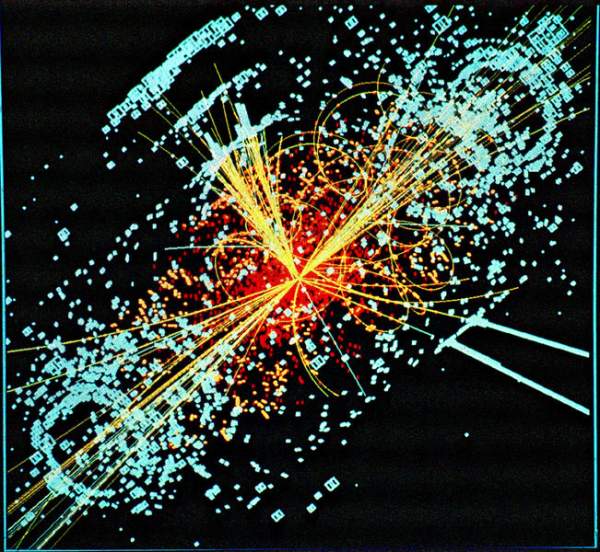

Chris - The first year of data, the data taken in 2010, the machine was effectively finding its feet. Every couple of weeks or so, the people who run the machine and get the collisions were able to make it almost twice as powerful in every two weeks. So, all the data from last year in a sense is almost exclusively the data that was taken in the last couple of weeks of operation. With that data, we've been able to start closing in on the Higg's Boson, we're not yet in a position to say whether it doesn't exist in any particular places, but closing on it; trying to find out whether or not supersymmetry exists, this is the work that I've personally been doing, we've managed to show that quite a lot of the places where people thought supersymmetry might exist, quite a lot of those are simply unlikely to be true! But it could still be hiding in various places. But in a sense with the data that we've taken, the limited data from last year, the Large Hadron Collider has been in some sense, just rediscovering the standard model, getting to the point at which it's about to be able to make even more important and exciting predictions.

Ben - And specifically, you work on ATLAS. It's very easy to fall into the trap of thinking that the LHC is just one big experiment, but there are actually lots of different detectors on it. Specifically, what is Atlas doing?

Ben - And specifically, you work on ATLAS. It's very easy to fall into the trap of thinking that the LHC is just one big experiment, but there are actually lots of different detectors on it. Specifically, what is Atlas doing?

Chris - Atlas is one of the two general purpose detectors. So as you said, there are four main detectors on the Large Hadron Collider, two of them have specialist roles. ATLAS is trying to basically look for anything - what are the basic building blocks of the universe? We're looking for any particles that we don't currently know about, we're looking to find the Higgs boson, and we're trying to cover all bases really. So, it's a general purpose experiment that is just looking for things that are out there that we're not really sure about, that we don't know exists yet.

Ben - Does this mean that you're getting pulled every which way by different people, demanding your data and interpreting it in different ways? As you said, you'll have theoretical physicist saying, "Well, I can use this data to find these hidden dimensions." You'll have the particle physicists saying, "I'm going to confirm or refute the existence of something very obscure." Do you really get to consider at one particular hypothesis for yourself or are you having to do a very general interpretation of these figures?

Chris - Personally, I do, and most of the people working on ATLAS do get to focus on a fairly narrow area, the area that interests them most. Because quite simply, there are so many people who are working on it, to cover all of those bases, that everyone divides the work amongst themselves. But even so, even in my case where I was chatting to some of the theorists in CERN before our data was released, when you still have to be quite secretive about what's there, so that the competition, don't find out about it and use it. Very often, they're saying "But why aren't you working on this? Why isn't your first paper on supersymmetry ruling out this particular type of supersymmetry or that type?" So yes, there's lots of tensions there, people are intrigued to convince us to work on that particular bit.

Ben - Have any of the LHC results so far - obviously, it's still early days - has anything actually told us that what we thought was right is actually wrong, rather than making big new discoveries, have we found out that our theories didn't quite stand up?

Ben - Have any of the LHC results so far - obviously, it's still early days - has anything actually told us that what we thought was right is actually wrong, rather than making big new discoveries, have we found out that our theories didn't quite stand up?

Chris - Not that I'm aware of so far. There are some little hints in some places of things where effectively I think the juries are still out and we might be needing to take more data when we look at what's coming on early this year. But I think at the moment, you could still say, the standard model rules okay. Our current ideas of particle physics haven't yet been shown to be completely wrong in any particular area.

Comments

Add a comment