The Bulging Arctic Ocean - Planet Earth Online

Interview with

British scientists recently used satellites to discover a bulging dome of fresh water in the Arctic Ocean....and it's getting bigger.

The lead author of the study was Katharine Giles from the Centre for Polar Observation and Modeling at University College London. Planet Earth podcast presenter Sue Nelson caught up with Katharine to find out more about this fresh water dome and why it's important...

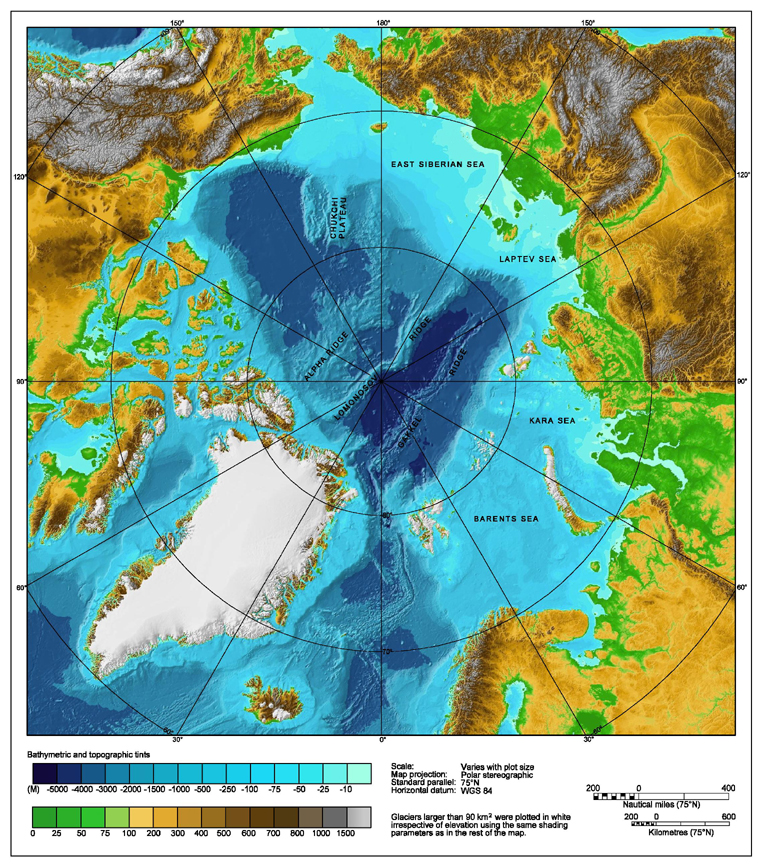

Katharine - Well, if you imagine you're looking down on the Earth, over the north pole and you can see the Arctic ocean, if you cast your eyes over to Canada, then go north of the Canadian coastline then you're in the Beaufort Sea. In the Beaufort Sea there's a circulation system called the Beaufort gyre, that's a rotating dome of water that rotates in a clockwise direction and what we've seen from the satellites is that dome increasing in height. The area is over 1000 kilometres across, so that's the distance between roughly, say, London and Venice, so it's quite a large area of the Arctic Ocean.

Sue - And when you say a dome, are we talking like a huge "Millennium Dome" rising of water above the sea surface?

Katharine - I imagine it more like a contact lens rather than a Millennium Dome, but it's still quite a large amount of water, it's about 8000 cubic kilometres of fresh water which is roughly 10% of all the fresh water that's stored in the Arctic Ocean.

Katharine - I imagine it more like a contact lens rather than a Millennium Dome, but it's still quite a large amount of water, it's about 8000 cubic kilometres of fresh water which is roughly 10% of all the fresh water that's stored in the Arctic Ocean.

Sue - Now, did you have clues that there was this body of fresh water in among a salty ocean?

Katharine - Well yes. Measurements taken from ships and moorings have shown that there has been an increase in fresh water over the past 15 years or so. But it is really difficult to make measurements in the Arctic because of the cold, dark winters and the ocean itself is covered by a layer of frozen seawater so it makes it hard for the ships to break through. This is why this satellite data is really useful. It helps to tie these snapshots of data taken from the ships and from the moorings to give us an idea of the overall picture of how the Arctic Ocean is changing.

Sue - Now you were using two European Space Agency satellites, ERS2 and Envisat. Were they both looking at the saltiness of the ocean or sea surface height in order to work out that, hold on, we've got this enormous of fresh water in the Arctic?

Katharine - What these satellites do - we use an instrument on board them called a radar altimeter and what that does is measure the elevation or the height of a surface. So, the data we're using is actually looking at changes in the sea surface height and from that, combining it with data from another satellite called Grace which measures changes in mass, we can estimate the change in the fresh water.

Sue - Is there a possibility that this fresh water could flow into other circulatory systems around the Earth?

Katharine - What we've seen in our data is that, with the fresh water that has been stored over the past 15 years, the winds seem to be controlling that storage of fresh water. So it's possible, if the winds then change direction, then that fresh water could be released out into the western Arctic, to the rest of the Arctic Ocean or beyond. And we're interested in that because changes in fresh water leaving the Arctic Ocean can influence the deep convection in the North Atlantic.

Part of the reason that Northern European enjoys a relatively mild climate in the winter is because of heat transported by currents that are derived from the Gulf Stream. So this circulation system, we call the global overturning circulation system, and that's bringing heat from lower latitudes up to the north in the ocean currents. As that water reaches the north it cools, it releases its heat to the atmosphere and the cooler water then sinks and more water moves up to take its place. This is a density driven circulation. The water is sinking because it's more dense, so if you then add less dense fresh water from the Arctic possibly you could effect that circulation system. In the past we've seen than an amount of water of a similar size to this 8,000 cubic kilometres may have influenced this convection in the Labrador Sea, which is one of the areas in the North Atlantic where you get this kind of overturning circulation. Whether that had an effect on our climate is something that we don't know.

Comments

Add a comment