Cancer and Stem Cells

Interview with

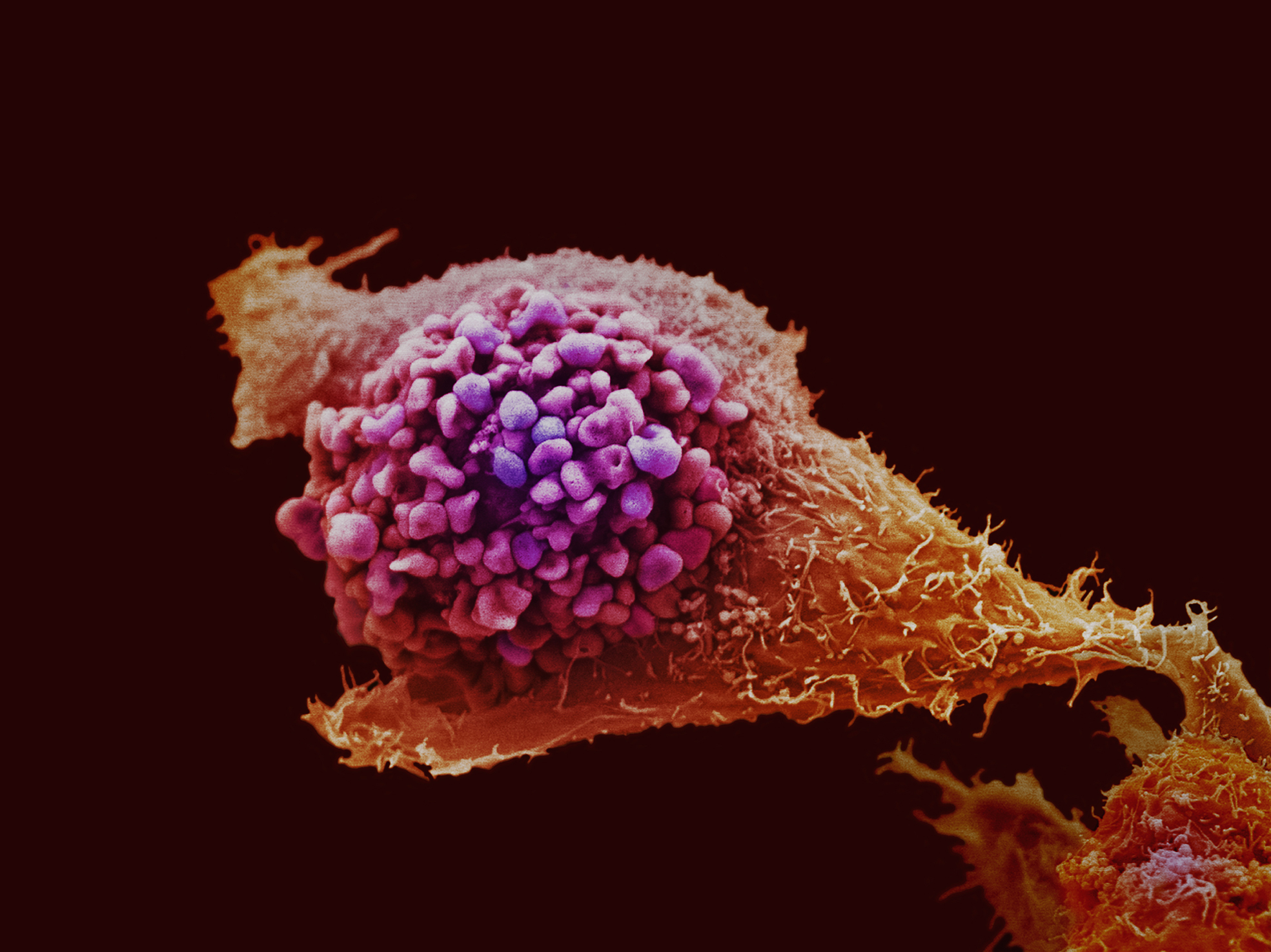

Kat - So your research is looking at cancer stem cells and stem cell biology. Going back to basics, how would you define cancer? Fiona - It's a disease in which cells in a part of your body start to grow in an uncontrolled way. Sometimes that will result in formation of a lump, for example if it's in your breast. But if you've got cancer in your blood, the cancer cells will be flowing around your body and then of course the danger is that the cells start to spread to other parts of the body.Kat - We've heard in this show about the idea of cancer stem cells, how long has this idea been around?Fiona - Its an idea which has been knocking around for, some would say almost a hundred years, since people first started looking at cells in cancers. Even back then, looking under the microscope people could see that not all of the cells in a tumour were the same. The idea is that some of the cells in the tumour are essentially innocuous, and other ones, the stem cells power the growth of the tumour and ensure that no matter what you do to try to get rid of the cancer the cancer will eventually re-grow.Kat - What sort of cancers have we found stem cells in so far? There seems to be new reports coming out all the time about it...Fiona - I think the first and most compelling identification of a stem cell in a tumour was work which was done on leukaemia, cancer of the blood. There's been very exciting reports of identifying stem cells in breast cancer, colon cancer, and other types of tumours such as something called a squamous cell carcinoma which effects the mouth, the oesophagus. It seems, really that almost every week evidence comes out for a stem cell population in another type of cancer.Kat - These discoveries have quite important implications for how we're treating cancer, what can we do with this knowledge now to take it forward?Fiona - You're right that it's very important, what we need to do is now design treatments which will target stem cells rather than the bulk of the tumour. For example, many current treatments for cancer are based on the idea that these are the cells that are growing very fast, however it might be that the stem cells are actually quite sluggish and so you're not doing any good just getting rid of the fast growing cells. Our idea is that we might be able to develop treatments which are more specific and are probably gentler for the rest of your body, they're not going to wipe out all of the normal cells which happen to be growing fast. That's the hope, and that's why people are really excited about stem cells now.Kat - So tell us a bit more about what's actually going on in your lab, you work on skin and the cells found in skin. What's new there?Fiona - My lab works on skin cancers and there are two main areas that we're interested in. One is trying to find out how different kinds of cells in the skin contribute to cancer; so we ant to identify the stem cells that drive the cancer. We're also very interested in bystander cells that seem innocuous, they might not be dividing themselves but we've found out they can actually be communicating with the stem cells and giving them encouragement to grow or else potentially holding them in check. This whole issue of what are different kinds of cells doing in a tumour is very interesting to us. The other thing we're working on is why it is that you get different kinds of tumour? In skin, you've got the outer covering of the skin, you've got sweat glands, hair follicles and so on... Different types of skin tumours are sort of caricatures of the normal differentiation that's going on. We'd like to understand how that works too.Kat - There are two main divisions of skin cancer, there's non-melanoma, and melanoma. What's the real difference between those two?Fiona - The difference is that the two types of cancer affect different cell types. Melanoma is a disease of the pigment cells of the skin called melanocytes. Non melanoma effects the cells that my lab works on, which are called keratinocytes. Kat - So how are the discoveries that you're making going to feed into cancer treatments in the future?Fiona - We have very good links with a lot of the clinical departments at Addenbrookes hospital. So what we do is we look at real tumours from real people, come up with ways to try to identify the stem cells, and then test the ideas that these are going to fire tumour development. Then we want to go back to our clinical colleagues and say "can you think of new treatments based around what we now know about the stem cells in the tumours?"Kat - So it's being a bit smarter about drug development, finding the targets and then finding the treatments?Fiona - Absolutely, but it's a slow process. You're really looking at probably ten years from getting a good proof of principle to having something which would benefit a patient in the clinic.

Fiona - It's a disease in which cells in a part of your body start to grow in an uncontrolled way. Sometimes that will result in formation of a lump, for example if it's in your breast. But if you've got cancer in your blood, the cancer cells will be flowing around your body and then of course the danger is that the cells start to spread to other parts of the body.Kat - We've heard in this show about the idea of cancer stem cells, how long has this idea been around?Fiona - Its an idea which has been knocking around for, some would say almost a hundred years, since people first started looking at cells in cancers. Even back then, looking under the microscope people could see that not all of the cells in a tumour were the same. The idea is that some of the cells in the tumour are essentially innocuous, and other ones, the stem cells power the growth of the tumour and ensure that no matter what you do to try to get rid of the cancer the cancer will eventually re-grow.Kat - What sort of cancers have we found stem cells in so far? There seems to be new reports coming out all the time about it...Fiona - I think the first and most compelling identification of a stem cell in a tumour was work which was done on leukaemia, cancer of the blood. There's been very exciting reports of identifying stem cells in breast cancer, colon cancer, and other types of tumours such as something called a squamous cell carcinoma which effects the mouth, the oesophagus. It seems, really that almost every week evidence comes out for a stem cell population in another type of cancer.Kat - These discoveries have quite important implications for how we're treating cancer, what can we do with this knowledge now to take it forward?Fiona - You're right that it's very important, what we need to do is now design treatments which will target stem cells rather than the bulk of the tumour. For example, many current treatments for cancer are based on the idea that these are the cells that are growing very fast, however it might be that the stem cells are actually quite sluggish and so you're not doing any good just getting rid of the fast growing cells. Our idea is that we might be able to develop treatments which are more specific and are probably gentler for the rest of your body, they're not going to wipe out all of the normal cells which happen to be growing fast. That's the hope, and that's why people are really excited about stem cells now.Kat - So tell us a bit more about what's actually going on in your lab, you work on skin and the cells found in skin. What's new there?Fiona - My lab works on skin cancers and there are two main areas that we're interested in. One is trying to find out how different kinds of cells in the skin contribute to cancer; so we ant to identify the stem cells that drive the cancer. We're also very interested in bystander cells that seem innocuous, they might not be dividing themselves but we've found out they can actually be communicating with the stem cells and giving them encouragement to grow or else potentially holding them in check. This whole issue of what are different kinds of cells doing in a tumour is very interesting to us. The other thing we're working on is why it is that you get different kinds of tumour? In skin, you've got the outer covering of the skin, you've got sweat glands, hair follicles and so on... Different types of skin tumours are sort of caricatures of the normal differentiation that's going on. We'd like to understand how that works too.Kat - There are two main divisions of skin cancer, there's non-melanoma, and melanoma. What's the real difference between those two?Fiona - The difference is that the two types of cancer affect different cell types. Melanoma is a disease of the pigment cells of the skin called melanocytes. Non melanoma effects the cells that my lab works on, which are called keratinocytes. Kat - So how are the discoveries that you're making going to feed into cancer treatments in the future?Fiona - We have very good links with a lot of the clinical departments at Addenbrookes hospital. So what we do is we look at real tumours from real people, come up with ways to try to identify the stem cells, and then test the ideas that these are going to fire tumour development. Then we want to go back to our clinical colleagues and say "can you think of new treatments based around what we now know about the stem cells in the tumours?"Kat - So it's being a bit smarter about drug development, finding the targets and then finding the treatments?Fiona - Absolutely, but it's a slow process. You're really looking at probably ten years from getting a good proof of principle to having something which would benefit a patient in the clinic.

- Previous The Role of Stem Cells in Cancer

- Next Decoding the Cancer Genome

Comments

Add a comment