Bacteriophage therapy for C. diff

Interview with

Microbiologist Martha Clokie, from Leicester University explained to Chris Smith how she is developing  viruses called phages to attack the Clostridium difficile - C. diff - bacterium, which can cause severe diarrhoeal disease, particularly in elderly patients in hospital...

viruses called phages to attack the Clostridium difficile - C. diff - bacterium, which can cause severe diarrhoeal disease, particularly in elderly patients in hospital...

Martha - Clostridium difficile is found naturally in the gut. What happens to patients is that, often, when they're given antibiotics to treat another infection, all the normal bacteria present in the gut are destroyed apart from Clostridium which can then massively expand in the gut area and it releases toxins, or poisons, which then cause very, very severe diarrhoea.

Chris - So, in fact, it's there already, but you effectively clear the way by destroying all the healthy or good bacteria with the antibiotics and that enables it to gain a toehold?

Martha - Yes, that's right. Well, often it can be present. In adults, perhaps about 5% of adults carry it normally. But one of the main problems of Clostridium difficile is that it makes spores and these spores, once they're in a hospital environment, are very, very difficult to remove. So, that's why outbreaks are often associated with hospitals.

Chris - So, you have a symptomatic patient, who puts some spores into the hospital environment and then another person comes along - even if they weren't carrying C. diff to start with - picks up the spores and then the toxic combo of those spores plus a whole host of antibiotics for another infection wipes out their normal bugs and enables them to then get colonized; and then get a major problem with their C. diff?

Martha - Yes, that is actually what happens.

Chris - So, if someone does get C. diff at the moment, how do we treat it?

Martha - Well, at the moment, there are two antibiotics that are routinely used to treat it - metronidazole and vancomycin. These antibiotics work in most patients, but some patients - they can be okay once they're on these antibiotics, but as soon as you remove the antibiotics, they just relapse and become sick again.

Chris - So, it's almost like the balance of microbes in them isn't quite right so they keep getting the C. diff coming back again?

Martha - Yeah, that's right.

Chris - So, what are you doing to try to tackle this?

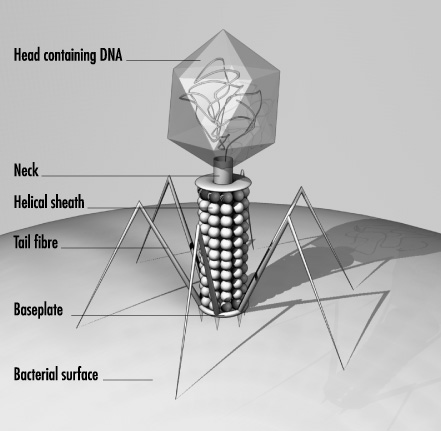

Martha - What we're doing is trying to find a new way to treat it. What we're looking for are viruses that naturally infect Clostridium difficile. Clostridium is a bacterium, so it's a single-celled organism, and viruses are much, much smaller, and they only exist when they're infecting another host. In the same way, you or I can have flu, Clostridium difficile has viruses that will only infect it. So, what we've been doing is actually trying to find these viruses in the environment and then see if they're effective to treat the patients who had Clostridium difficile.

Chris - This is called 'phage therapy', isn't it? This is not a new idea. Because, looking back in history before we had good quality antibiotics, people were trying to do this for a whole host of infections, particularly in Russia, weren't they?

Martha - That's right. Viruses that infect bacteria were first of all found nearly 100 years ago, and in the '20s, '30s and '40s, they were developed for many, many different diseases. Actually, in places like Georgia, they still use phages to treat many bacterial infections.

Chris - They don't pose any threat to the human that you give them to then?

Martha - No. They're very, very specific. There's no way that they could infect the human cell. They're very specific generally even to the bacterial group. This specificity might be really useful in something like Clostridium difficile, because whereas an antibiotic will suppress Clostridium, it will also kill many other species which you actually don't want to happen, whereas if you take a virus for Clostridium difficile, it would potentially only remove that infection and leave your other bacteria intact.

Chris - I suppose one other major bonus is that when the virus infects the C. diff bacterium, it then makes hundreds, if not, thousands of new bacteriophages programmed to attack C. diff. It will keep going on, amplifying the dose if you like, until it runs out of C. diff to infect and then it will just go away.

Martha - Yes. Well certainly, unlike a conventional antibiotic, when a bacterium is infected by a virus, it will raise perhaps 100 new viruses and they will then as you say, sort of search through the rest of the infected area until they run out of hosts to kill.

Chris - So, have you got some bacteriophages that will attack C. diff in this way?

Martha - Yes, we have, after fairly extensive searching, and a good team of PhD students and post docs. We eventually have come up with a very promising set of viruses that infect Clostridium difficile.

Chris - So, how will you deploy them? What's the next step?

Martha - Well at the moment, having got the viruses, we've shown that they work individually. So, we're now spending about a year or so, trying to design the optimal combination of viruses. Once we've done that, what we hope to be able to do is to then put them into a capsule which would then be able to pass through the stomach and then when it gets to the colon, the capsule would dissolve and the viruses would be released in the targeted way.

Chris - What about the fact that you mentioned that these bacteriophages - these viruses - are extremely selective and specific for the bugs they will infect. What about the fact that there may be different strains of C. diff out there in different people? Will you end up with effectively lots of C. diff that is immune to your phages?

Martha - Well, what we're doing at the moment and we're still in this work - I should emphasise we're still at quite a preliminary stage; we have the viruses and we're now testing which strains they infect. But what we intend to do is find the smallest number of viruses that infect the most number of strains that are circulating in patients. So, at any one time, there are a subset of strains that are causing the most number of cases of disease. So, what we'd hope to find is a little, small set of viruses that can infect these strains. But one of the real attractions of phage therapy is that as new strains come into circulation, we'll be able to then just find other viruses that are then effective in these new strains. So, you don't have to go right back to the drawing board. We just have to go back into our bank of viruses and find one that's effective on these strains...

Comments

Add a comment