Cholera in Haiti

Interview with

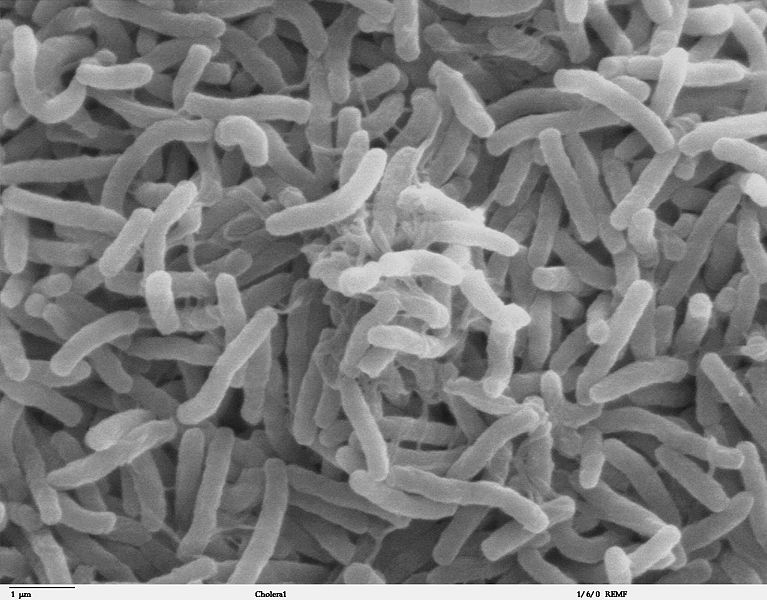

Hurricane Matthew caused devastation recently when it swept through the  Caribbean. The country worst hit was Haiti, and one legacy of the destruction is an outbreak of cholera. This bacterial infection produces a relentless watery diarrhoea so severe that it leads to serious dehydration, low blood pressure and even fatal organ failure. What's so sad is that Haiti had been cholera free until a well-meaning aid effort a few years ago brought the bug back there. Chris Smith heard how from The Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute's Nick Thompson...

Caribbean. The country worst hit was Haiti, and one legacy of the destruction is an outbreak of cholera. This bacterial infection produces a relentless watery diarrhoea so severe that it leads to serious dehydration, low blood pressure and even fatal organ failure. What's so sad is that Haiti had been cholera free until a well-meaning aid effort a few years ago brought the bug back there. Chris Smith heard how from The Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute's Nick Thompson...

Nick - Haiti's recent encounter with cholera started in 2010. Prior to that Haiti had been cholera free for about one hundred years and it really wasn't a country you would have associated with cholera outbreaks. But it was a country that was actually under world scrutiny in that the U.N. had sent a mission to Haiti to rebuild infrastructure in 2004 and cholera broke out in 2010. That timing, the 2010 outbreak of cholera and the circumstances that led up to that were very strongly associated with a fresh group of U.N. peacekeepers arriving from Nepal into Haiti to help rebuild infrastructure. And the U.N. have just admitted their role in the introduction of cholera into Haiti because the cholera that broke out in 2010 are very closely linked to those strains circulating within north India and Nepal at the same time.

Connie - So it was actually carried there from this rebuilding mission, the cholera was actually carried over to Haiti?

Nick - That's right. It's tragic really because, actually, the mission had incredibly positive and good intentions.

Connie - That's really quite devastating! So Haiti has just been hit by this huge hurricane and one of the big things that's being reported back from this is a massive surge in cholera - why is that and what's going on?

Nick - The whole point of the U.N. working in Haiti was to rebuild infrastructure in a country that didn't really have any infrastructure, and the reason that cholera took hold in Haiti was because most of the accommodation after the earthquake in 2010 was destroyed. People live in very ramshackled accommodation with almost no sanitation and access to drinking water and so there's been a lot of effort to improve that. And, of course, that's all been wiped away by the latest hurricanes, so Hurricane Matthew has destroyed much of the good work that's been done in trying to rebuild that infrastructure.

And so any destruction in the infrastructure, the sanitation, mixing of human waste and drinking water means that that population becomes incredibly vulnerable to this diarrheal disease. And cholera, epidemiologically, it's such an explosive disease, it can go from a very small number of cases to hundreds, or even thousands of cases in a very short period of time.

Connie - What can we do now to move forward and try to deal with this situation?

Nick - The primary treatment for cholera is oral rehydration. And so people get dehydrated very quickly but if they continue to resupply their body with contaminated water then they're just reinfecting themselves. So the classic response to cholera is to provide clean drinking water and to rehydrate those people that are most affected.

A vaccine to cholera is something that is one of the main strategies for treating and preventing outbreaks that we see in places like Haiti. And so there are several candidate vaccines that are being used and so investment in vaccination strategies is something that we hope to see more in the future.

Comments

Add a comment