Did humans kill the giant kangaroos?

Interview with

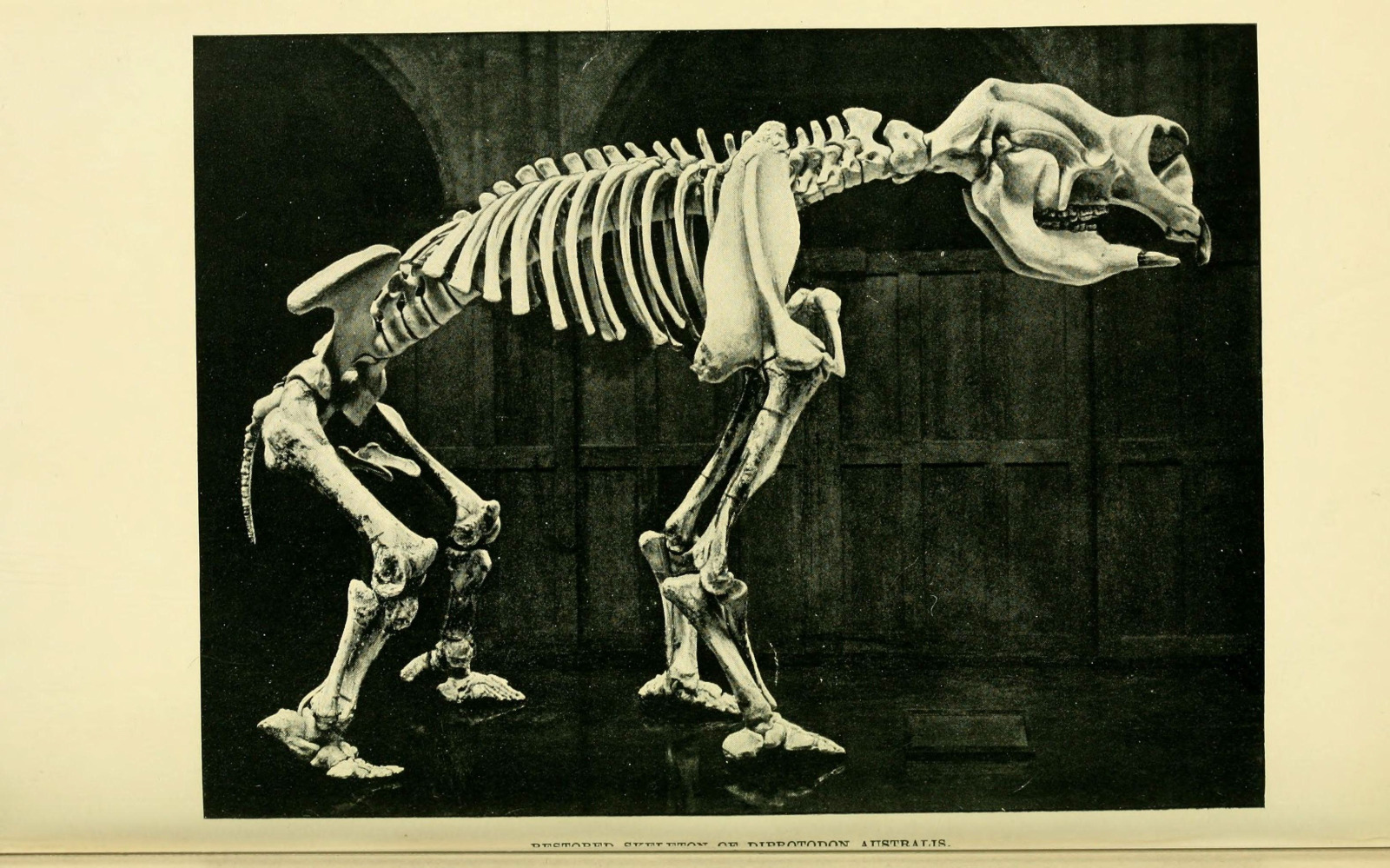

Did humans kill the giant marsupials? Australia used to look quite different from the arid deserts of today; it was more like the African savannah and was home to a range of huge animals including giant kangaroos and koalas that were up to a third larger than their modern day counterparts.

But, fossils found in caves across Australia show that around the same time the first humans arrived, 60 000 years ago, these so called giant megafauna disappeared. Chris Smith spoke with Gavin Prideaux, who studies these remains at Flinders University in Adelaide...

Gavin - A lot of my research is based in caves and right across southern Australia. The reason for that is, the preservation of the fossils in caves is exceptional. Caves are like a time capsule - very stable atmospheric conditions and oftentimes, caves open and close. So animals fall in or they're dragged in by predators and then the caves seal up and then occasionally, re-open again, allowing palaeontologists to access these deposits and then we get down, essentially like archaeologists, and excavate the different layers that contain the bones centimetre by centimetre.

Chris - How do you find the caves in the first place?

Gavin - Well actually, we're relying on all the avid cavers out there who love crawling around in caves and discovering new caves. Well-meaning cavers will bring bones to our attention, kangaroo bones or cow bones or sheep bones or dog bones, or whatever. But one times out of ten it's something really, really interesting and that's exactly what happened, for example, with our discoveries in the Nullarbor caves that a group of cavers discovered in 2002 and then we subsequently went out there based on the photographs of the specimens that they took. South central Australia is dominated by this vast treeless plain, the Nullarbor Plain, which is Latin for "no trees". There are thousands of caves and on this one particular trip, a group of cavers discovered three caves with megafauna fossils in each of them. No-one has found anything as good since out there and hundreds of caves that have been discovered and no-one had ever found anything before that. So, it was an amazing discovery and we've spent the last 12 years actually going out on trips out there and amassing a huge collection of remains that we're now wading through and starting to tell the story of how life changed in this area between 200,000 and a million years ago. Before people arrive on the scene, because once people are here in Australia, it's very difficult to tease the potential impacts of climate and the potential impact of human activities at par.

Chris - There are two phenomena going on then. You've got boom and bust which happens in any population, owing to natural climate change and superimposed on that is an effect, if any, owing to the arrival of modern humans in Australia.

Gavin - That's exactly right and we've done similar studies in the southwest of western Australia and similar studies at the World Heritage-listed Naracoorte caves in south-eastern Australia. What we see is that animal populations wax and wane with the coming and going of the ice ages over the last half a million years or so, but they don't go extinct. When we come to the late Pleistocene, let's say, 50 or so thousand years ago, suddenly a whole range of species start to become extinct.

Chris - In other words, these are animals you know they were there because they're in your caves and they can be dated to a point about 50,000 years ago. So, you know they were around until then and then suddenly they're not.

Gavin - Exactly. As soon as we come to about 40,000 years ago, they're gone.

Chris - And that is also the time when we think the first wave of humans got down to Australia.

Gavin - Exactly, and this is very strongly debated between the folks that believe the megafauna were driven to extinction by climate change, and when people say climate change in this context they mean increased aridity, versus the impacts of people, and there's two ideas they have for people. One is that people hunted them to extinction and another one is that they lit fires and changed the nature of the vegetation that the big herbivores were actually utilising. That idea is sort of waning somewhat. The evidence is not borne out by the evidence of landscape burning judging from charcoal records. Obviously, the charcoal is representative of a bushfire and we don't see a correlation of increasing bushfire at about 50,000 years ago. So, that idea is starting to wane. But of course, one of the problems of the human hunting idea is that we don't have direct evidence. But then you can counter that by saying, if we go back and we look at the deeper geological record, the fossil record, and we see the persistence of several species through time and then suddenly a new predatory animal arrives on the landscape and then a lot of those species disappear, the simplest explanation is that the arrival of that new species had something to do with the loss of the others.

Chris - Can we use Australia then as a sort of case study of the influence of humans and apply it to other parts of the world?

Gavin - It's an excellent case study because the timing of people arriving in Australia is probably going to emerge to have been about 60 or so thousand years. And so, we've got a good record for the previous few hundred thousand years of how the fauna are responding to climatic change in the absence of people. Then people arrive. We start to pick them up in the archaeological record, which species disappeared first, which ones hung around a little bit longer. And then of course, Europeans arrive in Australia 200 years ago and there's another massive spike in extinction. So in my view, there's basically three steps. You had the initial megafaunal extinctions driven by hunting probably a protracted period - 10 or 20,000 years by the first people who arrived in Australia, then a really low level of extinction, and another increase, maybe 6 or 7,000 years ago and then a massive increase 200 years ago. What we're looking at here is evidence of a mass extinction for the first time, and of course it's becoming a worldwide phenomenon now, driven by a species. Every other extinction through history, the other 5 mass extinctions going right back to 540 million years ago were driven by changes in the physical environment. An asteroid or a comet hitting the earth, volcanic activity - this is example that we've seen Australia is an excellent representative of this human driven mass extinction that really marks the last 50,000 years on this planet.

- Previous What wiped out the dinosaurs?

- Next Fancy popping an anti-fat pill?

Comments

Add a comment