Do manuscripts drift like DNA?

Interview with

Kat - DNA technology has revolutionised the world. We can use it to trace relatives, study how populations evolved and migrated, and even to answer questions about where life came from in the first place. But there's also been spin off for literary historians too, thanks to the work of scientists at Cambridge University's Biochemistry Department. They've taken computer programmes designed to compare DNA sequences and developed a way to use them, instead, to compare the words and spellings of ancient texts like the Canterbury Tales and even the Bible. What this can reveal is who copied who as versions of these writings were passed down from one generation to the next. Chris Smith spoke to Chris Howe:

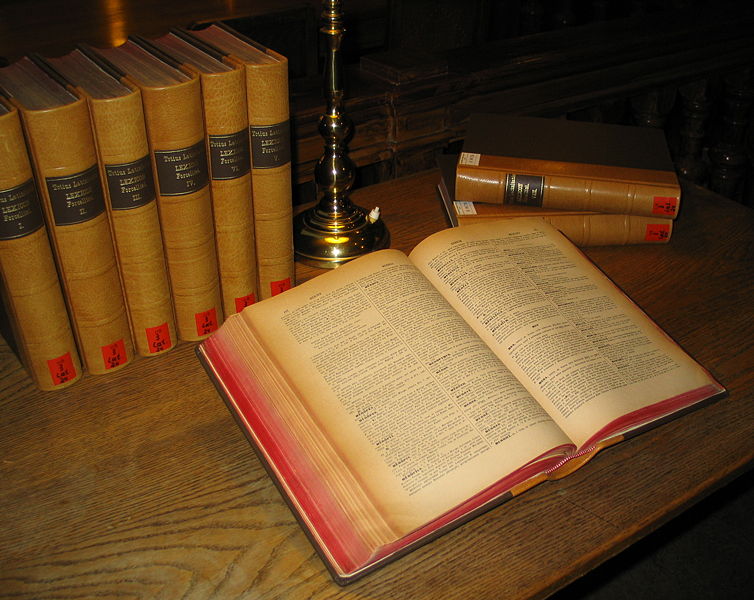

Chris H - We're interested in the parallels of how scribes copied manuscripts of medieval times and made mistakes, and then incorporated those mistakes as they made more copies of the manuscripts and how DNA gets copied and makes mistakes in the copying process that scientists call mutations. Those mutations get propagated as the DNA gets copied in turn.

Chris - So what you're saying is you could use the same tools that we've built to understand how DNA changes to understand how mistakes crept into literature going back for hundreds, if not thousands of years?

Chris - So what you're saying is you could use the same tools that we've built to understand how DNA changes to understand how mistakes crept into literature going back for hundreds, if not thousands of years?

Chris H - That's the approach, yes. We have a lot of computer programmes that allow us to look at DNA sequences from different organisms and work out what we call an evolutionary tree. Basically a kind of family tree of those organisms. What we're trying to do is to apply those computer programmes to look at different versions of a text to build up a family tree, as it were, of text.

Chris - So talk us through it. How would you start, what texts would you do and how would you convert the text into something the computer programme could understand? In other words, so it could think of the text as a bit of DNA.

Chris H - The computer programmes, as you say, are used to looking at bits of DNA. They're just a string of characters, which in the case of DNA, can be one of four possibilities. What we need to do is to take a piece of text and code it as though it looks like a string of characters. Basically, what we do is take each word and represent it by a character, as it were, in DNA.

Chris - What's the programme looking for in order to work out how the text has changed over time then?

Chris H - It's basically looking for changes that are shared by two or more organisms if we're dealing with DNA, manuscripts if we're dealing with texts. Then it assumes that if those two organisms have a change that the others don't have that they're related to the exclusion of the others. It can build up evolutionary relationships that way.

Chris - If I'm a scribe and I'm copying one ancient piece of text and I make a mistake or I put a certain combination of words together and then someone else, you, come along and copy my version you'd see the same combinations of wordings together. That's what your programme will be picking up, that relationship?

Chris H - Absolutely. That's how it works.

Chris - What have you been looking at in terms of real text and real analysis?

Chris H - The first experiments we did were a few years ago now on the Canterbury Tales, and in particular on the prologue to the Wife of Bath tale. That worked very well. The conclusions that we came to using our computer programme was really very similar to the kind of accepted conclusions that people had come to for years in the study of those texts.

Chris - That validated the method. What did you actually see? What was it proving?

Chris H - It's basically showing which manuscripts were copied from the same earlier version. That's something that's quite interesting for people studying texts, to know which versions of a text were copied from a same earlier version, maybe were copied in the same place or were copied by the same scribe. Since then we've moved on to different texts. We've done some work on the New Testament which is interesting. Most recently, we've worked on a political philosophy treatise by Dante (of Inferno fame), called Monarchia. Again, what happened there was were using data provided by people who'd been studying manuscripts for a long period of time and who had their own conclusions about the relationships between them and trying to test out our methods by using those data in our programmes. We didn't know at the outset what they were thing they might find or not find. We didn't even know what the text was. We were just told, "No, go away and see what you can find." We managed to work out relationships between different forms of text and then went back to the experts who'd been working on it and said, "Okay, this is what we found." They said: "That's amazing. That's exactly what the scholars have thought." Except, we can come to those conclusions very quickly and save the manuscripts scholars a lot of time, a lot of backs of envelopes in doing their own calculations.

Chris - What about spelling mistakes? One of the things that's very noticeable if you read old English is that you might see sulphur written with an 'f.' It might be written 'ph.' There must be loads of examples like that. Can your programme get round that?

Chris H - That's a very good point. For quite a long time, spelling was quite fluid. Because, therefore a scribe making their own copy might change the spelling in the same way in many different places in the manuscript we actually, for safety's sake, omit spelling changes from that kind of analysis. Similarly dialect words we omit as well. For example, a scribe working in Scotland would probably change 'church' to 'kirk' and we tend to omit those because two scribes in Scotland might therefore independently make the same changes.

Chris - Have you got people queueing up, all round the world to use this now? It sounds like an amazing tool. It could save so much time.

Chris H - People either love us or hate us, I think! There are some people who have said, yes we think this is a really powerful tool and we'd like to learn how to use it. Equally there are people who say this will never work, it can't possibly replace conventional scholarship. I think I would agree with them. It's actually not something that we would claim would replace conventional scholarship;. You should only follow a computer programme as far as an intellectual precipice, I always say, and not beyond.

Comments

Add a comment