Exploring Space: Robots vs Humans

Interview with

What can we learn from exploring Mars and are humans better than robots? Chris  Smith asks our panel about the scientific argument for human space travel. We started by considering the case for robots.

Smith asks our panel about the scientific argument for human space travel. We started by considering the case for robots.

Carolin - I think it's a no-brainer. Certainly in the short term, robots are the way to go. We've just heard about some of the hazards that humans face. Even if you can get them to Mars in one piece then the dangers on the surface, the reduced gravity, the radiation. The thing about robots is they're a lot less fussy, they're a lot less fragile, and you don't have to send so much kit with them. So in many ways, they are much more efficient way of exploring. Today, robots can do everything that humans can do. Maybe they don't do it so efficiently. Maybe we just have to be a bit more patient. We'll get our science a bit more slowly, but at the minute, there's no pressing need to be sending humans.

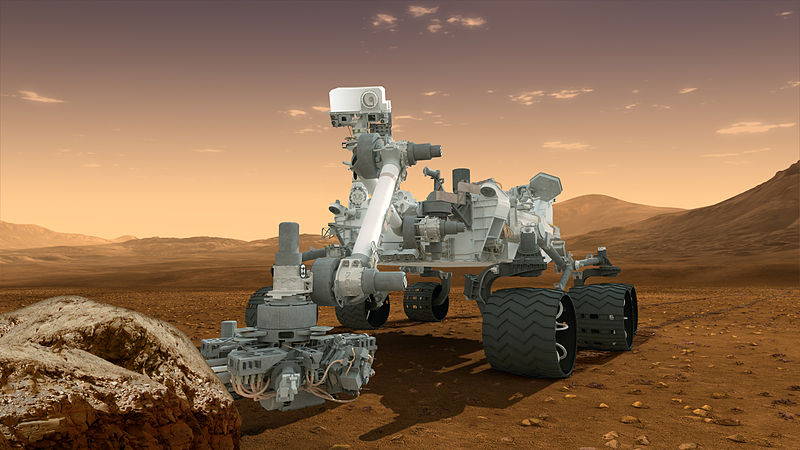

Chris - Sanjeev, you've been involved in the Curiosity Mission which is a pretty big mission. I mean, that's a mini-sized rover that's crawling around on Mars. Would you concur with what Carolin is saying?

Sanjeev - Not at all, I'm afraid. I'm a terrestrial geologist, I'm a geologist who works on Earth, does field work on Earth, and I've moved into the planetary sphere. Whilst Curiosity can do amazing things, it's incredibly slow for me. What we do in days, a human can do in minutes. That's the issue - is that, we've been on Mars for 3 years now, we've got some spectacular discoveries but we can't look around. We can't go this way or that way. We can make rapid decisions. We're not adaptable because of latency effects, et cetera. So, I think a human on Mars could very, very rapidly do this sort of geological characterisation - the geological science that we can do on Earth that even looking 10, 20 years ahead, a robot simply is not capable of doing just because of the human cognitive aptitudes.

Chris - It's just technology though, isn't it? I mean, it's just a question of writing better computer programmes to run these things better.

Sanjeev - Have you tried doing geology? It's very, very hard. The thing is that there's not simple patterns in the geological record. Scientifically, the first thing we're going to do when we get to Mars is actually look at the geological science. We will now understand the geological evolution of Mars. Did life evolve? Finding these things is incredibly difficult. There's a lot of rock on Mars. A rover maybe travels 20 kilometres in its lifetime. I think Curiosity has just done over 10 kilometres. Secondly, there's large areas of Mars which are very, very interesting that it will be very difficult to get robots too.

Chris - Carolin, you're sort of nodding and shaking your head in equal measure.

Carolin - Well, I agree that it would be a nice luxury to send human astronauts to do this job much more efficiently. I just dispute that it's actually required now. I mean, there are two questions being, one is of course, whether we can do all the science with the rovers and the orbiters, and even the stationery spacecrafts such as Phoenix. Yes, they can do it maybe more slowly. But it's a matter of, is getting the science just that much faster relevant for the huge cost it might bring and the huge danger to humans going out there.

Chris - Yeah, I was going to say. I mean, has to - when you're making a decision about doing research, weigh up the pros and cons in terms of what I can get bang for my buck. Sanjeev, what you're sort of suggesting is, "Yeah, let's get some humans on Mars" but the price, you think how much science we could actually do with the same spend both from orbit which is much cheaper and also, maybe even just from here on Earth.

Sanjeev - We can do a lot, but I think nobody is thinking that we're going to do this immediately so the plans are in the next 20 or 30 years for humans to Mars to do science properly. So, I think it's planning stages at the moment.

Chris - Richard, did you want to comment?

Richard - Well, I want to offer a compromise here, something that the European Space Agency and NASA are seriously looking at is to have a mission to Phobos or a mission to the orbits of Mars and then be able to control rovers on the surface. So that way, you eliminate the time delay and you can effectively have them as avatars on the surface.

Chris - When you say time delay, this is the problem that because it's so far to Mars that even at the speed of light, these radio controlled signals, you've got a latency of a delay of many - not just seconds, but minutes, hours.

Richard - Which is why they're building a lot more autonomy into the new rovers like the ExoMars rover which will be the European rover to Mars. But Tim Peake, the British European Space Agency astronaut who's flying to space station in December. He will be doing one of these experiments and actually, operating from the space station, a rover in the Mars yard which is a simulated Mars environment in Stevenage so actually, to simulate that.

Chris - Carolin, what's the price as well because you mentioned eluded to cost, everyone talked about cost but what do we think is actually likely to start costing?

Carolin - I've got absolutely no idea. I mean, just thousands of billions would be my guess. I mean, maybe that's an exaggeration. I just want to come back...

Chris - Ryan is just waving his hand. He's got an idea of the price then. What do you think the price tag is?

Ryan - The lowest estimated cost that I've seen for human Mars missions is on the order of $10 billion or so. So, for comparison with Curiosity which was around 2 billion, a factor of 4 more potentially in the costs for a human mission. Yeah, certainly, I think you can justify that.

Carolin - I just want to go back to Rich's compromise. If you're going to send astronauts all the way to Phobos, you're still exposing them to the same danger. It's still going to not actually cost an awful lot less. If you're going to go away to Phobos, you might as well just go to the surface of Mars. I don't think that's much of a compromise really.

Richard - I think one of the things that this is a compromised option eliminate at least in the short term is the problem of getting to Mars and getting back off again because we talked about sample return. When you talk to NASA scientists about this, no one has managed to get even a coffee cup-size sample of material off Mars. So, unless you're going to go on a one-way trip, which is what Mars1 is proposing, getting back is a real genuine concern.

Chris - I think Sanjeev, because your question and your point is that we want some samples and it's very hard to do this sort of science when you're not on Mars.

Sanjeev - More importantly, you don't just collect samples. As a geologist, you gain context and that's very difficult to do from a distance. And so, I think even doing it from Deimos or Phobos is really difficult. I think what's happening now is really a serious attempt to start thinking about resources on Mars and what you could use as propellant to get back. So I think it's not going to happen instantly, but people are thinking about that. They won't only consider that if they can do it, if the resources have had to be able to provide propellant to get humans back from the surface of Mars.

Chris - Propellant equals rocket fuel.

Sanjeev - Right.

Carolin - I think the key thing though that we're all in agreement is that we need robots at the minute. Whether or not we're going to be sending human astronauts to Mars, they're vital as scouts really to prep - just as precursors, to find where the resources are, the possible landing sites, to assess the climate, the radiation damage. We need to test things like, we were just talking about the launch, the landing technology, the piloting, and even just delivery of equipment, habitat, fuel, food. Everything that we need is all going to be robotic even long before we send the astronauts. So, whether or not you send the astronauts, we still need to develop the robot technology, just as that scouting and that testing ground.

Chris - In other words, we need them anyway so we might as well just solve this problem in the course of solving the next one, don't we? Now, the other question is of course, why do we want to go to Mars? What can we learn about Mars? Interestingly, this year's Christmas lectures at the Royal Institution are all about the future of space travel and space exploration, and they're being delivered by UCL's Kevin Fong.

Kevin - Mars, I think is a large piece of the puzzle when it comes to asking a question of how ubiquitous life is in the universe. We know that 4 billion years ago, conditions on Mars were at least similar to, if not the same as they were on Earth. We know that that was around about the time that life first arose on our planet. And so, if we go to Mars and it proves to be sterile and always has been sterile then it means that Earth is indeed very, very special and it's something particularly special about it that allows life to claw its way and then develop. If we go there and find that there is life now or there has been life on Mars, it probably means that life is ubiquitous in the universe because it suggests that wherever life has a chance, it will claw in at least in some basic form. So, I think it is essential that we explore Mars. I think it has some of the most important answers that we seek in the 21st century.

Comments

Add a comment