Foetal grafts persist in Parkinson's

Interview with

Foetal nerve grafts persist in Parkinson's patients for decades...

This week a new paper has been released about Parkinson's Disease - the  degenerative brain disorder which is characterised by shaking tremors and irrevocably linked to Boxing great Muhammad Ali.

degenerative brain disorder which is characterised by shaking tremors and irrevocably linked to Boxing great Muhammad Ali.

There is currently no cure for Parkinson's but 20 years ago, doctors took the radical step of trying to treat the disease by injecting new nerve cells into patient's brains.

However the technique was controversial as the cells they used were from human foetuses which came from elective abortions.

Now, a research paper published this week, indicates the technique was successful. And it means that doctors may now be able to use new methods where the cells come from the patients themselves rather than from abortions. One of the pioneer researchers, Ole Isacson, told Chris Smith more...

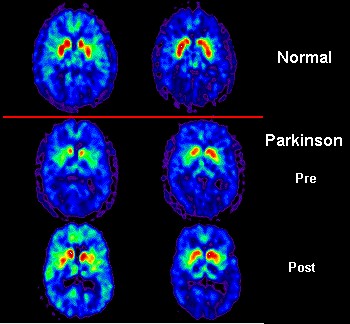

Ole - Parkinson's disease - what happens in the brain is that a particular group of neurons that are called dopamine neurons, you start off at birth with about a million inside of your brain, they will degenerate over time. The brain compensates for that for many years usually. When you have lost about 70% of those dopamine neurons, it will be very difficult for the brain to initiate a movement. So Parkinson's disease is primarily seen as a movement disorder. There's also usually a shaking tremor and a rigidity in the muscle.

Chris - So, how do people think we should be treating Parkinson's disease? What do we think is the best way of overcoming the problem?

Ole - It was clear quite early, or many years ago in fact, that if you added dopamine or a substance that can make dopamine that people could start moving better again. But it became apparent that after about 5 to 10 years, those drugs usually lost their efficacy. And so, several of us many years ago started thinking about ideas which were more radical at the time which was to re-implant those nerve cells that were lost. And the step is quite conceptually new in that, this paper we're publishing suggested that actually in the future, we'll be able to repair circuits, not just by providing chemicals, but by providing new cells.

Chris - And the cells that you're seeking to put into the brain, where are they coming from?

Ole - Well, this study is actually very important because it used to prototype what we're going to do with the future with stem cells. In this particular study that actually started 15, 16 years ago in Canada, we went along to study transplanting cells from elective abortions. To do that, almost 6 foetuses had to be dissected and the little piece of the midbrain where these new born nerve cells are, it's about a cubic millimetre. They were then dissociating into a liquid and injected back into the patient's brain. Now, the reason I call that a prototype because that's a very difficult process to do indeed and by some, considered unethical.

Chris - The idea being that these foetal cells, when you put them in, they can wire themselves in and turn into dopamine producing nerve cells, helping to make up some of the deficit that the patient's brain previously were suffering from.

Ole - That's exactly right, Chris. The work that's been actually occurring over the last two decades confirm that, and this paper is however very important because it establishes that the cells remain very healthy in our study here up to 14 years after implantation, which actually coincides with the longevity of function which is even more important to the patient. So, current studies indicate that one set of implanted neurons can work for up to at least 20 years and these patients actually have no use for drugs anymore. Therefore, it's quite remarkable.

Chris - So, how did you actually do the study? Did you have to go and get post-mortem tissue from people who had one of your transplants but have now unfortunately died and asked, has the transplant survived in these people?

Ole - Yes. This study which commenced many years ago has had of course, 20 years ago, have had patients that have died over time obviously by different reasons than the transplants. For example, heart disease is common. We have obtained in each one of those cases the brain for post-mortem studies as we have been fortunate to be able to study these brains in great detail.

Chris - And what are the implications of this study? You've looked in these brains, you've seen that the cells that you put in 14 to 20 years ago appear to be surviving for that long. Why is this important?

Ole - Well, it's very important because Parkinsonian patients will not be receiving foetal cells in the future by any stretch of the imagination. Over the last 3 or 4 years, we've been able to produce the very same dopamine neurons we had obtained by elective abortion by reprograming skin cells from patients and then making those cells into the equivalent of a stem cell that we're able to show that the dopamine neurons that had died in Parkinson's disease could be generated in a dish. So, in other words, the very importance of this study is that it lays a foundation for us to now pursue the same cell by transplantation that we can now obtain in the dish. And that would allow us to scale up to a degree that maybe cell therapy, if it turns out to be effective in clinical trials, it would be a real alternative to the current methods that the patients have for this very terrible disease.

Chris - Ole Isacson with some very good news for Parkinson's sufferers and he published that work this week in Cell Report. It's interesting Kat isn't it because 20 years ago, I remember those trials going on and it just goes to show how long the research cycle is between us doing something and then us finding out what the implications and outcomes really are.

Kat - Absolutely and it's incredible how stem cell technology has changed in that intervening time even in just the past 5 years. So, I think it will be really interesting to maybe re-visit this, maybe if we're still broadcasting in 20 years' time and see where the new crop of stem cell therapies have gone with this.

Chris - Because like you say, everyone thought at that time, the only way we were going to be able to do this was to use foetal tissue. The idea of taking a skin cell from an adult and being able to reprogram it to turn it into a nerve cell, so you'd get your own cells back. People thought you were mad if you said that that was even feasible. They didn't think it would be possible to do.

Kat - And certainly now it is, but like with Ole's research it takes you 20 years to find out how well they worked.

Comments

Add a comment