The Genetics of Swine Flu

Interview with

Chris - Now also in the news this week, how could you have missed it, the fact that we are perhaps on the verge of a pandemic or perhaps not? People are very worried about this swine influenza from Mexico but surely more answers than any can be obtained by sequencing the virus and understanding what its genetic story is and joining us now from Imperial College in London is Professor Wendy Barclay. She is an influenza virologist. Hello Wendy!

Wendy - Hello!

Chris - Good to have you with us on the Naked Scientists. Tell us a bit about where we stand with this, what have we learned so far from looking at the genetics of this virus?

Wendy - Well, over the course of last weekend and then into last week, most of the genes of a number of different isolates of this virus has been sequenced. That information has been shared by scientists over the web, which allows us all to have a look and see whether or not this virus has got any of the particular traits that we would associate with, for example, a highly pathogenic virus that we can begin to predict, what to expect as this virus spreads into people and what sort of actually we should be preparing ourselves to take.

Chris - What about where it came from Wendy? What does the sequence actually tell us about its origins?

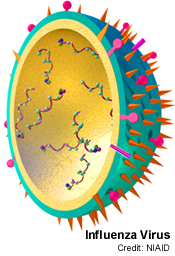

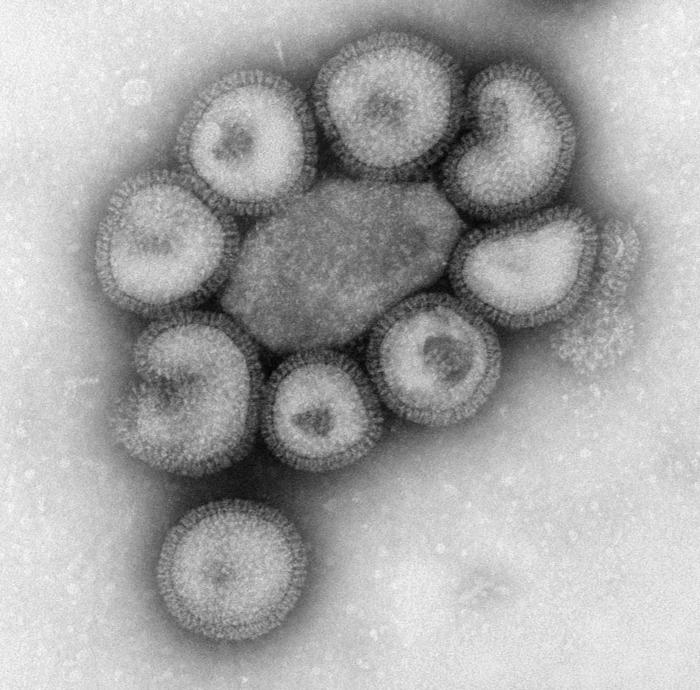

Wendy - Very interesting. The swine influenza is quite a complicated beast, it turns out. Your listeners may or may not know but influenza virus has its genome splitting to eight discrete pieces known as the segments of RNA and in general, each one of those species encodes one protein although some of them encode two. So there's about 11 proteins spread on eight species and you could think of these a little bit like chromosomes if you like, that they are discrete physical entities that encode genes.

Wendy - Very interesting. The swine influenza is quite a complicated beast, it turns out. Your listeners may or may not know but influenza virus has its genome splitting to eight discrete pieces known as the segments of RNA and in general, each one of those species encodes one protein although some of them encode two. So there's about 11 proteins spread on eight species and you could think of these a little bit like chromosomes if you like, that they are discrete physical entities that encode genes.

Now we can tell by looking at those segments of RNA that way, way back some of those RNA segments were once segments of viruses that were circulating in humans and also in birds and in pigs. So what happened with swine influenza back in the late 1990s is that a particular strain appeared in the Americas which contained gene segments from at least three different viruses from three different types of hosts, humans, birds and pigs, and this constellation has been known as the 'Triple-reassortant genome' or TRIG.

That seems to be a very happy virus. It was spreading around the pigs in the Americas very well, shuffling a little bit on the outside its antigenic properties but the basic backbone of the virus seemed pretty fit. Now what's now happened is that that pig virus from the Americas has somehow muddled up with another pig virus which until recently was really only known about in Europe and the two of those have mixed together, one would imagine, in a pig which perhaps became co-infected by the two viruses and have produced this final Mexican flu.

Chris - Why do you think that this interesting combination has now suddenly decided that it's going to jump out of the pig and start infecting humans?

Wendy - Yeah, that's a super question and obviously something that we need to understand and lots of people are having to think about that the TRIG genome that was existing in the Americas since the 1990s didn't do that until now.

The insides of the virus have stayed more or less the same so the best bet is that it's the particular combination of the outside genes, the hemagglutinin and the neuraminidase, on the TRIG backbone which has allowed this jumping to occur but it's early days to say that yet and obviously that is just based on sequence gazing, what we are going to need to do now is real biology to try and understand why those surface genes, the H and the N, the particular ones come together and allow this jump to happen.

Chris - Thank you Wendy for explaining that. Could you just finally tell us what are the big priorities for virologists to now do in relation to this pandemic virus or potential pandemic virus, what would the big questions that people are now beginning to ask, be?

Wendy - Yes, well I mean obviously from a practical point of view we've got to know is this virus susceptible to antiviral drugs and will it remain so? So the good news at the moment from the gene gazing is that yes it is at the moment as far as we can see and of course we know that people are responding well to timely flu treatments but we also know that single-point mutations can render such viruses resistant.

So we need to know, for example, will this particular virus tolerate those mutations or will there be a sort of cost to them which would mean that any resistant virus is emerged where we are unfit or no longer transmissible between people.

So we need to know, for example, will this particular virus tolerate those mutations or will there be a sort of cost to them which would mean that any resistant virus is emerged where we are unfit or no longer transmissible between people.

Another key question is whether or not vaccines that we have already can offer any sort of immunity? To be honest there's so little sequence, the homology between human strains that we have been vaccinating people against and this one, that's unlikely but we certainly need to check it out to be sure. And finally the question that is sort of big and known is whether or not this virus is going to change anymore than it has already?

We know it has managed to jump into people but is it going to stay the same as it is now or is there a chance that it could mutate and if it did mutate, could it get any more virulent or is it more likely to go the other way and sort of adapt back to it's host and live in harmony.

Chris - Well let's hope not. Thank you very much. That's Wendy Barclay who is Professor of 'Flu Biology, Virology at Imperial College in London.

Comments

Add a comment