Lost at sea

Interview with

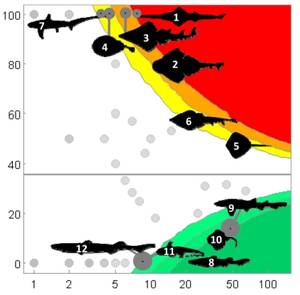

Over half of all shark and ray species are "threatened or near threatened" according to new estimates, with species most affected being those that are large and live in shallow water, easily accessed by fisheries. The state of the world's  oceans and what lies beneath the surface is relatively unknown, as Nick Dulvy reveals...

oceans and what lies beneath the surface is relatively unknown, as Nick Dulvy reveals...

Nick - For the last fifty years, our activities and our quest for food have eroded a lot of the biodiversity on the face of the planet. And growing up throughout this, I often wondered what was happening underneath the water's surface. And indeed for 20 years now, we've become increasingly concerned about how much we're taking from the oceans. Catches are rarely recorded. Even when they are recorded, they're not recorded in sufficient detail for us to know how much of each species is being taken. The next problem is, we might have some insight in to what is being taken from the ocean. The challenge is to figure out what's left in the ocean and are those populations viable.

Chris - So how in this study have you sought to try to understand what the real picture is?

Nick - Well, IUCN, the International Union for Conservation of Nature, has developed a way of effectively crowdsourcing science. And individual PhD students and fishery scientists around the world may have a good detailed understanding of their particular part of the coast or the ocean. And what IUCN specialises in is bringing all of those people together so we can bring all of their individual jig-saw pieces together to make sense of them on the global scale and this is particularly important for sharks and rays. It's very hard for any one scientist to tell us about the status of any one species and it's because many of these species are not just found in the waters of one country or one region, so our main methodology is really bringing people together and bringing their data sets together. And we did this over a period of 18 years. We had 17 workshops around the world that were attended by 302 experts and scientists.

Chris - So out of this big metro analysis, what trends have emerged and are the results in line with the worrying signs that we were picking up from the incidental reports that have been filtering through over recent years?

Nick - What we have estimated is that one-quarter of the world's sharks, and rays, and chimaeras are threatened with an elevated risk of extinction and we also find that a relatively small proportion are actually safe, so less than a third and closer to a quarter, on the Red List are the least concerns. So this is a group of species that has got a very high proportion that are threatened and a very low proportion that are actually safe.

Chris - That's a terribly high number, isn't it?

Nick - Indeed. The only animal groups that are more threatened than the sharks and rays are the amphibians. About a third of amphibians are threatened and the stony corals that make up our coral reefs.

Chris - Now those are the animals that we are studying. What about the ones we are not?

Nick - Indeed. One of the most alarming findings for us as a scientific community was that around 487 species or half of the total were classified as data deficient. That means we did not have enough information with which to determine to the extinction risk status and of course that means that some fraction of that huge group of organisms are actually likely to be threatened.

Chris - People talk about a population point of no return. Once you diminish a population down to a threshold level where the genetic diversity means that there's no prospect really of recovery, for the 25% that are in that really threatened bracket, have we breached this population point of no return or is there still hope to rescue the situation?

Nick - What this study doesn't really tell us is when sharks will go extinct. Part of the reason for that is that we're concerned about the status of sharks because of their rate of decline and just like dropping a ball out of your hand, gravity inevitably takes it to the ground. And what's happening here is that unless we halt these declines, then the gravity of declining populations will inevitably lead to their extinction. We don't know when that will happen but we hope we will have enough time in which to implement management and conservation action.

Chris - What's it going to take?

Nick - Well, a large part of the problem is that fisheries managers and conservation biologists are just spread incredibly thin. They're very often not very well resourced. When I worked at the UK government Fisheries Agency, there was only myself and another colleague who had a side interest in sharks and we pursued that side interest, but we were never paid to work on that. But I think as these red listings highlight species of concern in particular places, then it motivates governments and government agencies to focus on these species and that's what our next job really is to do is to use these Red List assessments and the concerns raised by them to motivate more resources being put into conservation action and fisheries management.

Comments

Add a comment